|

Shane Harris contributed reporting recovered through WayBackMachine Website

A photo of Mike Waltz, JD Vance, and Pete in the Oval Office. Andrew Harnik / Getty

U.S. national-security leaders included me in a group chat about upcoming military strikes in Yemen. I didn't think it could be real.

Then the

bombs started falling...

The reason I knew this is that Pete Hegseth, the secretary of defense, had texted me the war plan at 11:44 a.m.

This is going to require some explaining.

The Houthis, an Iran-backed terrorist organization whose motto is,

...soon launched attacks on Israel and on international shipping, creating havoc for global trade.

Throughout 2024, the

Biden administration was

ineffective in countering these Houthi attacks. The incoming

Trump administration promised a

tougher response.

'Signal' is an open-source encrypted messaging service popular with journalists and others who seek more privacy than other text-messaging services are capable of delivering.

I assumed that the Michael Waltz in question was President Donald Trump's national security adviser. I did not assume, however, that the request was from the actual Michael Waltz.

I have met him in the past, and though I didn't find it particularly strange that he might be reaching out to me, I did think it somewhat unusual, given the Trump administration's contentious relationship with journalists - and Trump's periodic fixation on me specifically.

It immediately crossed my mind that someone could be masquerading as Waltz in order to somehow entrap me.

It is not at all uncommon these days for

nefarious actors to try to induce journalists to share information

that could be used against them.

It was called the,

A message to the group, from "Michael Waltz," read as follows:

The message continued,

Read, "Here are the attack plans that Trump's advisers shared on Signal."

The term principals committee generally refers to a group of the senior-most national-security officials, including the secretaries of defense, state, and the treasury, as well as the director of the CIA.

It should go without saying - but I'll say it

anyway - that I have never been invited to a White House

principals-committee meeting, and that, in my many years of

reporting on national-security matters, I had never heard of one

being convened over a commercial messaging app.

One minute after that,

Nine minutes later,

At 4:53 p.m., a user called "Pete Hegseth" wrote,

And at 6:34 p.m. "Brian" wrote,

One more person responded:

The principals had apparently assembled.

In all, 18 individuals were listed as members of this group, including,

I appeared on my own screen only as "JG."

We discussed the possibility that these texts were part of a disinformation campaign, initiated by either a foreign intelligence service or, more likely, a media-gadfly organization, the sort of group that attempts to place journalists in embarrassing positions, and sometimes succeeds.

I had very strong doubts that this text group was real, because I could not believe that the national-security leadership of the United States would communicate on Signal about imminent war plans.

I also could not believe that the national

security adviser to the president would be so reckless as to include

the editor in chief of The Atlantic in such discussions with

senior U.S. officials, up to and including the vice president.

At this point, a fascinating policy discussion commenced.

The account labeled "JD Vance" responded at 8:16:

The Vance account goes on to state,

The Vance account then goes on to make a noteworthy statement, considering that the vice president has not deviated publicly from Trump's position on virtually any issue.

A person identified in Signal as "Joe Kent" (Trump's nominee to run the National Counterterrorism Center is named Joe Kent) wrote at 8:22,

Then, at 8:26 a.m., a message landed in my Signal app from the user "John Ratcliffe."

The message contained information that might be

interpreted as related to actual and current intelligence

operations.

The Hegseth message goes on to state,

A few minutes later, the "Michael Waltz" account posted a lengthy note about trade figures, and the limited capabilities of European navies.

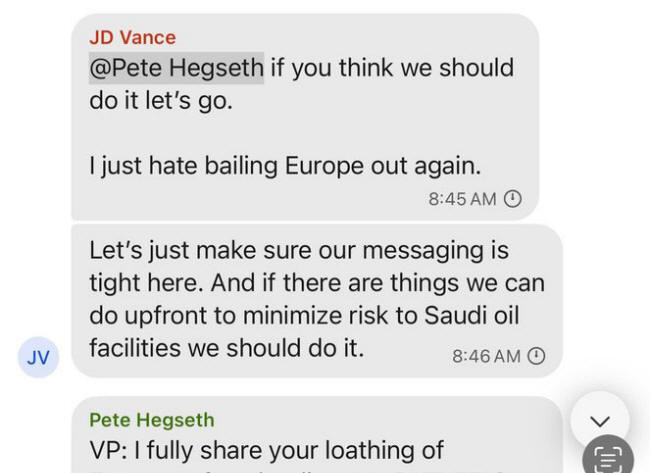

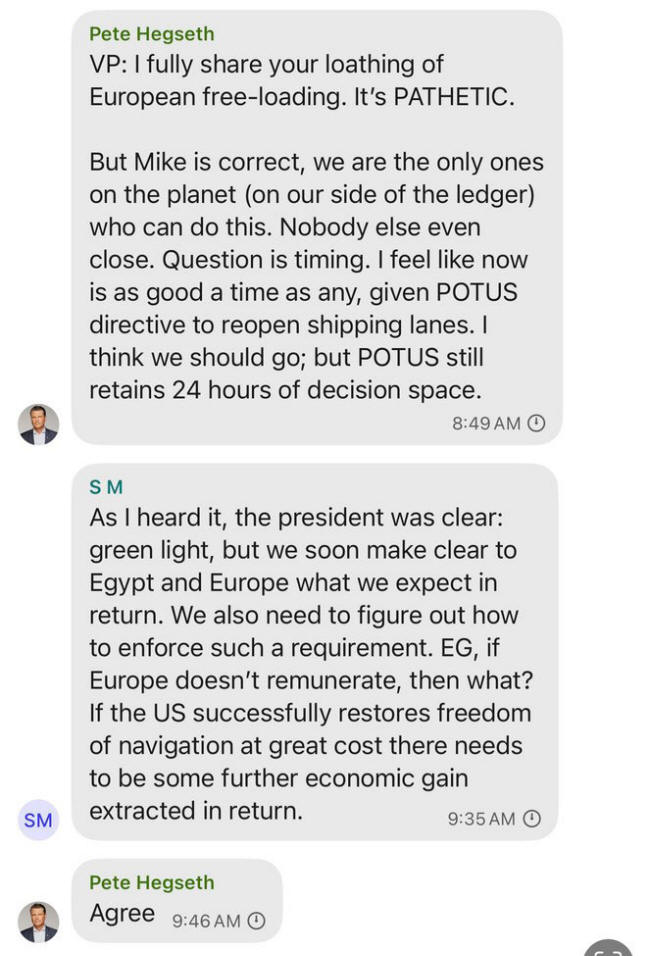

The account identified as "JD Vance" addressed a message at 8:45 to @Pete Hegseth:

The user identified as Hegseth responded three minutes later:

At this point, the previously silent "S M" joined the conversation.

A screenshot from the Signal group shows debate over the president's views

ahead of the attack.

The last text of the day came from "Pete Hegseth," who wrote at 9:46 a.m.,

After reading this chain, I recognized that this conversation possessed a high degree of verisimilitude.

The texts, in their word choice and arguments, sounded as if they were written by the people who purportedly sent them, or by a particularly adept AI text generator.

I was still concerned that this could be a disinformation operation, or a simulation of some sort. And I remained mystified that no one in the group seemed to have noticed my presence.

But if it was a hoax, the quality of mimicry and

the level of foreign-policy insight were impressive.

I will not quote from this update, or from certain other subsequent texts.

What I will say, in order to illustrate the

shocking recklessness of this Signal conversation, is that the

Hegseth post contained operational details of

forthcoming strikes on Yemen, including information about targets,

weapons the U.S. would be deploying, and attack sequencing.

According to the lengthy Hegseth text, the first detonations in Yemen would be felt two hours hence, at 1:45 p.m. eastern time.

So I waited in my car in a supermarket parking lot. If this Signal chat was real, I reasoned, Houthi targets would soon be bombed.

At about 1:55, I checked X and searched Yemen.

I went back to the Signal channel.

At 1:48, "Michael Waltz" had provided the group an update. Again, I won't quote from this text, except to note that he described the operation as an "amazing job."

A few minutes later, "John Ratcliffe" wrote,

Not long after, Waltz responded with three emoji:

Others soon joined in, including "MAR," who wrote, "Good Job Pete and your team!!," and "Susie Wiles," who texted,

"Steve Witkoff" responded with five emoji:

"TG" responded,

The after-action discussion included assessments of damage done, including the likely death of a specific individual.

The Houthi-run Yemeni health ministry reported

that at least 53 people were killed in the strikes, a number that

has not been independently verified.

A screenshot from the Signal group shows reactions to the strikes.

The Signal chat group, I concluded, was almost certainly real.

Having come to this realization, one that seemed nearly impossible only hours before, I removed myself from the Signal group, understanding that this would trigger an automatic notification to the group's creator, "Michael Waltz," that I had left.

No one in the chat had seemed to notice that I

was there. And I received no subsequent questions about why I left -

or, more to the point, who I was.

I also wrote to Pete Hegseth, John Ratcliffe, Tulsi Gabbard, and other officials.

In an email, I outlined some of my questions:

Brian Hughes, the spokesman for the National Security Council, responded two hours later, confirming the veracity of the Signal group.

William Martin, a spokesperson for Vance, said that despite the impression created by the texts, the vice president is fully aligned with the president.

I have never seen a breach quite like this.

It is not uncommon for national-security officials to communicate on Signal. But the app is used primarily for meeting planning and other logistical matters - not for detailed and highly confidential discussions of a pending military action.

And, of course, I've never heard of an instance

in which a journalist has been invited to such a discussion. Conceivably, Waltz, by coordinating a national-security-related action over Signal, may have violated several provisions of the Espionage Act, which governs the handling of "national defense" information, according to several national-security lawyers interviewed by my colleague Shane Harris for this story.

Harris asked them to consider a hypothetical scenario in which a senior U.S. official creates a Signal thread for the express purpose of sharing information with Cabinet officials about an active military operation.

He did not show them the actual Signal messages

or tell them specifically what had occurred.

The Signal app is not approved by the government for sharing classified information.

The government has its own systems for that purpose. If officials want to discuss military activity, they should go into a specially designed space known as a sensitive compartmented information facility, or SCIF - most Cabinet-level national-security officials have one installed in their home - or communicate only on approved government equipment, the lawyers said.

Normally, cellphones are not permitted inside a SCIF, which suggests that as these officials were sharing information about an active military operation, they could have been moving around in public.

Had they lost their phones, or had they been

stolen, the potential risk to national security would have been

severe.

But this argument rings hollow, they cautioned,

because Signal is not an authorized venue for sharing information of

such a sensitive nature, regardless of whether it has been stamped

"top secret" or not.

That raises questions about whether the officials may have violated federal records law:

Several former U.S. officials told Harris and me that they had used Signal to share unclassified information and to discuss routine matters, particularly when traveling overseas without access to U.S. government systems.

But they knew never to share classified or sensitive information on the app, because their phones could have been hacked by a foreign intelligence service, which would have been able to read the messages on the devices.

It is worth noting that Donald Trump, as a candidate for president (and as president), repeatedly and vociferously demanded that Hillary Clinton be imprisoned for using a private email server for official business when she was secretary of state.

(It is also worth noting that Trump was indicted

in 2023 for mishandling classified documents, but the charges were

dropped after his election.)

Now the group was transmitting information to someone not authorized to receive it.

That is the classic definition of a leak,

even if it was unintentional, and even if the recipient of the leak

did not actually believe it was a leak until Yemen came under

American attack.

In his text detailing aspects of the forthcoming attack on Houthi targets, Hegseth wrote to the group, which, at the time, included me,

|