|

by Christopher Bird and Oliver Nichelson

from

Tesla'sFuellessGeneratorAndWirelessPowerTransmission

Website

In the Pike’s Peak mountain range, overlooking Colorado Springs, an

eccentric Serbian-born inventor began at the dawn of the twentieth

century a series of experiments on electrical properties of the

atmosphere in a newly built laboratory 8,000 feet above sea level.

Ringing the laboratory were freshly painted signs warning all who

chanced to stumble onto the premises that their lives were in

danger.

Probing the heavens from atop the laboratory’s roof was a 154-foot

mast, anchored by guy-wires, supporting at its peak a hollow copper

ball 4 feet in diameter. Its purpose was to collect and store an

electrical charge inconceivably large for its day.

The new installation was the brain-child of Nikola Tesla, the

immigrant from Austro-Hungary who, only a few years earlier, had

developed the means to found a new electrical industry in North

America. The invention making this possible was the alternating

current generator which today generates powers for billions of

people all over the globe.

Paired to the generator was Tesla’s alternating current motor

without which lathes, dentists drills, revolving doors, water pumps,

elevators, and thousands of other instruments now so crucial to our

civilization would not operate.

The twin inventions transformed electricity, known since long before

Benjamin Franklin had hoisted his kite and key skyward, from a

scientific curiosity to the principal agent of a technological

revolution which altered the lifestyle of humanity. Up to that time,

electricity had been delivered only in the form of direct current

through a method developed by the American genius, Thomas Edison, to

power that famous product of his imagination: the light bulb.

The drawback of Edison’s system was its

inability to transmit direct current - which quickly turns to heat

when pushed through wires - over any appreciable distance with the

assistance of a booster generator for every mile of distance

traveled. Tesla’s new approach to the problem rendered Edison’s

method obsolete at a stroke.

By harnessing alternating current,

Tesla was able, as early as 1895, to relay a massive quantity of

electricity produced by the hydroelectric turbines at Niagara Falls,

to users in Buffalo, 22 miles distant. without interceding

generating stations.

The man who almost single-handedly wrought a revolution in applying

electricity to man’s needs was an enigma to his contemporaries. So

advanced were his concepts that the science and industry of his day

were unable to comprehend the essence and scope. Half a century

before they became widely known, he was experimenting with radar,

robots, particle accelerators, and high temperature plasma.

Possessed of such unfathomable power to anticipate the future of

technology, Tesla has caused many to wonder whether he might not

have been an extra-worldly super-being visiting for a time among

lesser earthly creatures.

Born in 1856 in the village of Smiljan—in today’s Yugoslavian

Croatia—the young Tesla was urged to study theology by his father, a

former professional soldier turned priest. As a child, he

continually had strange visions. Frequently, it was only necessary

for a word to be spoken in order for him to actually see the object

which it represented appear in phantom guise before his eyes and

remain there for hours.

To banish unsolicited mental pictures, Tesla conjured up his own

images, but, because of his limited experience in the world, they

soon became repetitive.

Later he recalled that it was as if he could

no longer add more frames to a movie-like reel in his mind. To

surmount this problem, he decided to create new thought-forms from a

world beyond the day-to-day life he knew.

Of these he later wrote:

I saw new scenes. These were at

first blurred and indistinct and would flit away when I tried to

concentrate my attention upon them. They gained strength and

distinctness and finally assumed the concreteness of real

things. I soon discovered that my best comfort was attained if I

simply went on in my vision further and further, getting new

impressions all the time, and so I began to travel; of course,

in my mind.

Every night, and sometimes during the day, when

alone, I would start on my journeys, see new places, cities and

countries, live there, meet people and make friendships and

acquaintances and, however unbelievable, it is a fact that they

were just as dear to me as those in actual life, and not a bit

less intense in their manifestations.

When at age seventeen Tesla first turned

to invention, he realized that his childhood ability to visualize

objects in three dimensions, once a curse, had become a precious

gift, allowing him to materialize mentally the design of any machine

he wished to create, to take it apart and put it back together, or

simply to observe it in action.

When he built real-life machines to

the specifications of his own imagining, they operated exactly as he

had foreseen.

The acute sensitivity which allowed

Tesla to convert his mental constructs to hardware was not

unaccompanied by a host of bothersome impressions, known to few

other mortals. In a biographical sketch written in 1919, he

described his violent aversion to women’s earrings and his obsessive

fascination for crystals and plain surfaces, his revulsion at

touching the hair of another person, the fever simply looking at a

peach would arouse, and the nausea brought on by merely glancing at

small squares of paper floating in a liquid. Evil spirits, ghosts,

and ogres filled him with unremitting dread.

It was not until Tesla read, in Serbian translation, a remarkable

novel, Aoafi, by the Hungarian writer Josika that he

was given a clue about how to control the random unearthly forces

coursing through him. The novelist’s observations introduced him to

an ingredient of the human psyche the existence and force of which

he had not yet suspected: will-power. Extrapolating from hints in

the text, he began to practice inner control his resolution to

separate his intent from the clutch of habit at first would fade all

too easily, but after doggedly pursuing his effort over several

years, he was able to reach a state in which will became identical

with desire.

He had so perfected this ability in

later life that he could control his body as adroitly as any circus

acrobat. At fifty-nine, while walking from his New York laboratory to

his residence, he suddenly slipped on the ice and saw his legs go

out from under him. As this was happening his mind, calmly observing

his predicament, sent instant messages to his muscles.

He twisted his body in midair and was

seen by stunned passersby to land on the sidewalk in a handstand.

The extraordinary exercise of will-power was not always at Tesla’s

command; it was especially lacking during times of illness. As chief

engineer at the first telephone exchange in Budapest in 1881, he

worked himself around the clock to a nervous breakdown, at which

point he was again visited by sensations only detectable to an

individual of his special sensitivity.

As he later recounted:

"In Budapest I could hear the

ticking of a watch with three rooms between me and the

time-piece. A fly alighting on a table in the room would cause a

dull thud in my ear. A carriage passing at a distance of a few

miles fairly shook my whole body. The whistle of a locomotive

twenty or thirty miles away made the bench or chair on which I

sat vibrate so strongly that the pain was unbearable.

The ground

under my feet trembled continuously. In the dark I had the sense

of a bat, and could detect the presence of an object at a

distance of twelve feet by a peculiar creepy sensation on the

forehead.”

It was also in Budapest that Tesla, his

health recovered, experienced a flash of illumination which first

revealed to him how his alternating current devices might work.

While strolling in a park with a friend,

he was suddenly moved to declaim lines from Goethe’s Faust:

The glow retreats,

Done is the day of toil.

It yonder hastes, new fields of life exploring.

Ah, that a wing could lift me from the soil

Upon its track to follow, follow soaring.

Hardly were the words out of his mouth

than he was struck by a vision of a magnetic whirlwind turning a

motor. Excited, he exhorted his friend to watch the motor run, first

in one, then in the opposite direction, and to observe carefully all

the parts playing a role in its action.

The companion, who could

only see Tesla staring inanely at the setting sun, became so alarmed

that he began dragging the engineer towards a park bench. Snapping

out his trance, Tesla refused to sit down and went on and on with a

detailed description of his vision, which, over the next several

days, he worked up in detailed blueprints in his mind, where they

remained stored for the next six years.

This vision was the foundation upon which Tesla invented the

rotating magnetic field so fundamental to his alternating current

devices. All his life Tesla worked in privacy so strict that it

bordered on secrecy. A recluse by nature, he lived for many years in

New York City’s Waldorf Astoria, where he could be seen dining

alone, in full evening dress, at a table set aside for him by the

maitre d’.

He maintained his remoteness from the

world in his Rocky Mountain retreat, where he discovered new

principles of energy and its transmission which have never been

fully elaborated or understood to this day because Tesla and his few

surviving collaborators, managed to keep them as hermetically veiled

as the teachings of secret societies.

From what is known, it appears that by

calculating the speed of thunderstorms, he realized that electrical

waves emitted from distant lightning bolts came through in bursts of

energy depending on how far away from his receiver the clouds

producing them had moved . It was after observing the electrical

effects in the earth of thunderbolts that Tesla discovered the

presence of stationary waves in the planet.

Some of his conclusions must have

mystified even his assistants, for his memoirs reveal that his

supersensory powers were still fully active during his sojourn in

the Rocky Mountains:

In 1899, when I was past forty and

carrying on

my experiments in Colorado, I could hear very

distinctly thunderclaps at a distance of 550 miles. The limit of

audition for my young assistants was scarce more than 150 miles.

My ear was thus over three times more sensitive, yet at that

time I was, so to speak, stone deaf in comparison with the

acuteness of my hearing, while under the nervous strain.

The supersensitive receiver invented by

Tesla to track electrical storms also was the first manmade device

to detect radio signals coming from the cosmos, over thirty years

before a Bell Laboratories researcher, Karl Jansky, picked up

similar signals and came to be recognized as the “father of radio

astronomy.”

Soon after the article appeared, Tesla was granted

U.S. Patent No.

685,957 for a version of his receiver, the somewhat cryptic title of

which was “Apparatus for the Utilization of Radiant Energy.”

In the technical idiom of the Victorian

Age, he described the operation of the receiver as follows:

By carefully observing well-known

rules of scientific design of instruments, the apparatus may be

made extremely sensitive and capable of responding to the

feeblest influences or disturbances from very great distances

and too feeble to be detected or utilized in any of the ways

heretofore known, and on this account the method here described

lends itself to many scientific and practical uses of great

value.

In Colorado, Tesla was also the first

and only person to create fire balls, phenomena which remain a

complete puzzle to science. These balls often appear in the wake of

thunderstorms; moving slowly, they bounce when they strike the earth

or any solid object. No one knows why they are more common in

certain parts of the earth, such as Sweden or Australia, or why they

only average a lifetime of no more than five seconds, although some

have been observed to last up to five minutes.

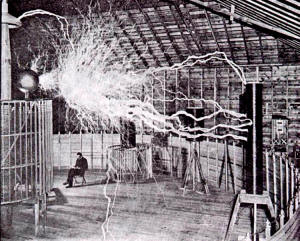

To produce ball lightning, Tesla built a

huge model of what the world knows as the “Tesla coil,” a radio

frequency transformer of unheard-of dimensions and power. It

produced 12 million volts and created sparks, or artificial lighting

bolts, over 100 feet long.

When first energized, it blew out the

generator of the Colorado Springs Lighting and Power Company; Tesla

supervised the rebuilding.

Tesla’s record output has only recently

[1975] been equaled in Utah, where in a 60,000 square foot hangar at

Wendover Air force Base, 16 miles from Great Salt Lake’s Bonneville

Flats, Robert Golka, a Massachusetts-born engineer working under a

classified contract, has achieved the production of 15 million

volts.

Golka hopes that by duplicating Tesla’s equipment as exactly as

documentation will allow he can be the second man to produce ball

lightning for U.S. government agencies interested in its possible

application to thermonuclear power generation.

Golka made a careful study of

Tesla’s Colorado Springs diary at the

Nikola Tesla Museum on Proletarian Brigade Street in Belgrade,

Yugoslavia, where his entire inventive and literary estate was

transferred after his death.

The estate comprises 100,000 documents, or more than enough to keep

researchers with a technical understanding of the four foreign

languages in which they were written busy for years. Included are

13,780 pages of biographical material; 75,000 pages of letters to

6,900 correspondents; 34,552 pages of scientific articles, notes,

drafts articles, and patents; all of Tesla’s diplomas, scientific

honors, and newspaper clippings; 5,297 pages of technical drawings

and plans; and over 1,000 photographs.

While in his Colorado experimental

station, Tesla realized that the earth’s atmosphere is analogous to

an electric wire of specific length. Such a wire can only

accommodate a set number of electrical frequencies and their

harmonics, just as a string pressed at a fret, and thus shortened or

lengthened, will reverberate only a specific family of sound.

Tesla therefore believed that, were

enough electrical energy pumped into the earth’s atmosphere - which

stretches from the ground to the ionosphere, an electrically

conducting set of layers 30 miles, and higher, above it - and

oscillated at specific frequencies, a growing number of harmonic

waves would be set in motion within it.

Propagated around the globe,

they could then be used, thought Tesla, not only for radio

transmission but for wireless broadcast of electricity into homes

and industrial plants, as well as to ships at sea and aircraft, if

all were equipped with suitable receivers.

As he wrote:

Impossible as it seemed, this

planet, despite its vast extent, behaves like a conductor of

limited dimensions. The tremendous significance of this fact in

the transmission of energy in my system had already become quite

clear to me. Not only was it possible to telegraphic messages to

any distance without wires, as I recognized long ago, but also

to impress on the entire globe the faint modulation of the human

voice. Far more significant is the ability to transmit power in

unlimited amounts to almost any terrestrial distance and without

loss.

More importantly, Tesla’s research led

him to the conclusion that the electrical properties of the

negatively charged earth and its positively charged upper atmosphere

could be used to supply an almost unlimited quantity of electricity.

To test his ideas, Tesla built a mammoth 75-million-watt “magnifying

transmitter” able to light a bank of two hundred 50-watt light

bulbs, of his own design, for a total of 10,000 watts of energy, at

a distance of 26 miles. (The California Institute of Technology has

only recently achieved an optimal figure of 43% in the transmission

of microwaves over a maximum distance of 1 mile.)

No wires of any

kind were utilized. The energy passed right through the ground. And

Tesla claimed that only 5% of it was wasted.

If Tesla’s design was correct, his scheme could supplant burgeoning

projects for solar heating going forward in a number of countries

and for which the United States Energy Research and Development

Agency has budgeted more than $125 million dollars for the fiscal

year 1977. The same system, Tesla hinted, could be adapted to

military purposes in the form of a defensive weapon.

He wrote in Liberty magazine (9 February

1935):

My invention requires a large plant,

but once it is established it will be possible to destroy

anything, men or machines, approaching within a radius of 200

miles. It will, so to speak, provide a wall of power offering an

insuperable obstacle against any effective aggression.

What effect such a system would have on

intercontinental ballistic missiles is anyone’s guess. The

possibility that the Soviet Union may already be at work on

potential military aspects of a Tesla system was suggested, however

tangentially, by a story appearing 29 October 1976 in the Washington

Star, headlined: “Who’s Fouling Up Global Radio? - FCC Prods Soviets

on Mystery Signal."

The article called attention to a

“superpowerful mysterious radio signal” emanating from somewhere in

the region between Minsk and the Baltic Sea which, over several

months, had been disrupting maritime, aeronautical, and amateur

radio communications to the point where various channels have become

virtually useless.

All attempts by the United States

Federal Communications Commission, which received several hundred

complaints, the International Amateur Radio Union in England, and

the International Telecommunications Union in Geneva, to elicit

precise information from the Russians about the exact location and

purpose of the signal have failed.

Tesla also alluded to the fact that his ultra sensitive receiver

could be modified to pick-up, store, and amplify the natural

vibrations constantly going on in the upper reaches of the earth’s

gaseous envelope. Such a “solar collector” making use of charged

particles instead of heat or light energy, would work night and day

and in any weather. Containing not a single moving part, it would

have the unnerving appearance of just “sitting there” and putting

out electricity - seemingly creating something from nothing.

If Tesla had been the only person to have made such a claim, his

evidence might have been discounted and forgotten. However, others,

inspired after reading of his achievement, have followed in his

footsteps.

Writing on 10 June 1902 to his friend Robert U. Johnson, editor of

Century Magazine, Tesla included a clipping from the previous day’s

New York Herald about one Clemente Figueras, a woods and forests

engineer in Las Palmas, capital of the Canary Islands, who had

invented a device for generating electricity without burning fuel.

Figueras’s subsequent history is not known, but his achievement

prompted Tesla, in his letter to Johnson, to claim priority for

first having developed a device similar to the one produced at Las

Palmas and, especially, for having revealed the physical laws

underlying it.

On 29 July 1920 the Seattle Post Intelligencer ran a

front-page spread, including a three-column-wide picture under the

title “Hubbard Coil Runs Boat on Portage Bay Ten Knots an Hour; Auto

Test Next.” The boat, 18 feet long, was propelled across Seattle’s

Lake Union by a 35 HP electric motor attached to the mysterious

coil, the invention of Alfred M. Hubbard, a nineteen year-old

gadgeteer.

The newspaper account provides a fascinating description of a small

“fuelless” power unit generating a very large amount of electricity.

It also recounts some of the

difficulties Hubbard experienced in overheating of wires:

The boat circled about the bay and

returned to the wharf with never a slackening of speed. The wires

connecting coil and motor had begun to heat under the excessive

current, and fearing that some part of the coil might give way

under the extra heavy strain put on it, Hubbard declined to

permit the motor to be run continuously for any length of time.

It was tried out later several times, after brief periods, which

allowed the wires to cool, and its power apparently showed no

diminution.

Hubbard’s coil, no larger than a small

wastebasket, measured only 11 inches in diameter and 14 inches in

length. Its output of current totaled 35,000 watts (280 amperes at

125 volts), or enough power to light 350 100-watt bulbs. The

electric motor had to be specially reconstructed for use in

conjunction with the coil (however, no details were given).

The inventor maintained that his power

unit could operate for years, and that it could drive a large

touring car at normal speed, illuminate a medium sized office

building, heat seven two room apartments, and allow an airplane to

fly all the way around the world without stopping. Because his

device derived its energy from the surrounding air, Hubbard called

it an “atmospheric power generator.”

From the Post lntelligencer account it

is clear that the young Washingtonian’s generator was quite

different, as far as the principle of its construction was

concerned, from Tesla’s concept.

“In general,” allowed Hubbard, “it

is made up of a group of eight electro-magnets, each with

primary and secondary windings of copper wire, which are

arranged around a large steel core.”

Obviously, the Seattle newspaper

accounts do not provide sufficient data to allow us to reconstruct

the Hubbard coil or even to learn the amount of wire used, its size,

or the number of turns around the axis.

In July 1973 a former resident of Seattle then living in Houston,

Texas, wrote to the Post Intelligencer to inquire whether it had

published any additional data on Hubbard since the appearance of the

articles in the 1920s. In answer to this query, Don Carter, a staff

reporter, wrote a follow-up story, dated 16 July 1973 and headlined

“Saga of a Boy Inventor and His Mystery Motor.”

Carter hints that the Hubbard invention

was remanded to oblivion by officialdom.

“As the Texas reader remembers it,”

he wrote, “the marvelous invention was quickly squelched by the

federal government, which wisely acted to prevent the

manufacture and sale of this static electric generator to avert

a national financial panic.”

Carter also dug up the fact that, after

making a trip to Washington, D.C., to press for a patent on his

device, Hubbard was indicted for using his talents to produce and

operate radio transmitters over which rumrunners out of Canadian

territory were advised, during Prohibition, when and where it was

safe to land their boats and offload contraband liquor. He was

cleared of this charge by a federal jury in 1928.

Shortly after Hubbard’s exoneration, the

Detroit Free Press ran a story on 25 July 1928 with a banner

headline “Engine Works, Needs No Gas Nor Any Other Fuel - Whirling

of Globe May Be Utilized for Driving Planes, Automobiles and Other

Machinery at High Speeds.”

The new “fuelless motor” had been

designed by one Lester Jennings Hendershot of West Elizabeth,

Pennsylvania, and successfully tested at Selfridge Army Airfield

outside Detroit in a demonstration witnessed by the world-famous

aviator Charles Lindbergh, who testified that the motor worked.

When the Seattle Post-Intelligencer published the same story,

Hubbard, suspecting that his own invention might have been purloined

by Hendershot, complained to a staff reporter, R. B . Bermann, who

three days later wrote an article headlined “Hubbard Believes

Mystery Motor Based upon His Own Invention.”

Though Hubbard waffled on exactly how

the energy for his motor was actually acquired, he continued to

insist that there was no great difference between the instrument

tested in Detroit and his own. Trying to establish a link between

his work and Hendershot, he did provide a vivid description of the

obstacles he had come up against.

As he told the Post Intelligencer

reporter:

I never heard of this Lester J.

Hendershot who is demonstrating the motor, but it must be

remembered that I worked on the invention for two years in

Pittsburgh, in 1921 and 1922. It was Dr. Greenslade who

represented the people who were financing me at the time - but,

of course, if the people who bought out most of my interest in

the invention were to bring it out as their own machine, they

would probably do it through a man with whom I never worked.

When I made my discovery I was only

sixteen years old, and until that time I never even had an ice

cream soda. So you can imagine that a couple of thousand dollars

looked mighty big to me. I never hesitated for an instant when

the people who were financing me insisted on taking fifty

percent interest from the start, and I didn’t protest when they

kept demanding that I sign over more and more of my rights.

But

at last I just quit them cold.

Hendershot was not more forthcoming than

his Seattle predecessor when it came to clearly explaining the

principle of his motor’s functioning. He maintained that it would

run for more than 2,000 hours before any recharging of the magnet

was required,” that it could “make its own electricity” to “start

itself,” and that, “based on electromagnetism applied to the rotary

motion of the earth,” the energy which drove it was the same as that

which caused a magnetic compass to rotate.

It appeared that Hendershot had first

conceived of his motor, not in a waking illumination like Tesla, but

in a dream, while experimenting in 1925 on ways of building an

improved compass for airplanes.

The officer in command of Selfridge Field, Major Thomas Lanphier, at

first highly skeptical, was soon impressed with Hendershot’s motor.

“I believe,” he told the press,

“that the invention is something more than the pipe dream I

thought it was when I first heard of it. It has no hidden

batteries or other phony business. Anyone can convince himself

of its efficacy by just throwing the switch and watching it

run.”

The Hendershot motor attracted the

attention of personages of national stature who deprecated or

extolled it, depending on whether they viewed it as a threat to

their security (financial or otherwise) or as a boon to mankind. On

the one hand, the Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics

announced that it would examine the motor.

On the other, William S. Knudsen, soon

to become president of General Motors, denounced it as impractical

“bunk,” not failing to add that the internal combustion motor would

be around for a long time. Another antagonist was Dr. Frederick Hoffstetter, who, as head of his own research laboratory in

Pittsburgh, went to the length of hiring a lecture hall in New York

City, were he announced to a large audience that the whole

Hendershot story reported in the press was a fraud.

He exhibited a model of the motor which

he had brought with him, showed that it would not work, and, to

clinch his argument, reported that he had found a carbon pencil

battery concealed within it. The furor surrounding the motor led

Hendershot to dismantle it and conceal it in a location known only

to him. The Free Press announced that, within thirty days, it would

be put in operation in an airplane.

Then, on 9 March 1928, the same paper’s Washington correspondent

reported that Hendershot was lying in serious condition in the

District of Columbia’s Emergency Hospital, where he had been taken

after receiving a severe electric shock from his motor while

demonstrating it to patent attorneys.

After his recovery, Hendershot disappeared from public view for more

than thirty years, resurfacing only once in 1945, when he sent a

letter to the Free Press from the Standard Ship Company’s U. S. Navy

Office in San Pedro, California. The letter accused scientists who

had earlier belittled his efforts of now repeating his statements

word for word. At the end of 1960, Hendershot’s device, now called a

“magnatronic generator,” became the object of a research grant

proposal made to the U. S. Navy’s Office of Naval Research.

The submission was made by Force

Research, a group of some twenty Californians who, to quote the

proposal, were,

“united in one centrally administered body to

correlate their findings on experiments and problems which otherwise

have been unsolved.”

Organized by Lloyd E.Cannon, a retired

department head at the Weyerhauser Lumber Company, it included the

controller of Capitol Records in Hollywood, the owner of the

Precision Tool and Clock Company in Pasadena, an oil tycoon from

Long Beach, a research engineer at the California Institute of

Technology’s Jet Propulsion Labs in Sierra Madre, the president of

McCaffrey Research Corporation in Palm Springs, and Dr. Daniel Fry,

who a few years earlier had written about his incredible contact

with an Unidentified Flying Object in his classic, The White Sands

Incident.

Fry was to be project manager, Hendershot project engineer, for the

development of the magnatronic generator for which the group sought

$150,000 from the navy. The proposal provided the names of

twenty-two persons (including businessmen, attorneys, contractors,

publishers, and engineers) who had witnessed the generator in

action, including a Colonel Lanphier, now retired.

The generator was reported to have lit a

100-watt lamp with “induced radio frequency energy. “ A Federal

Communications Commission engineer who investigated the locale of

the experiment told his superiors that he could find “no condition

which could account for such a phenomenon,” and Bernard Linden, the

engineer in charge of the FCC’s Los Angeles office, wrote to one of

the experiment’s witnesses, Dr. Robert Fondiller, a New York

engineer, for information on the apparatus used “when observing the

above condition. “

The Force Research project came to an end in 1961, when Lester

Jennings Hendershot, his dream of providing the world with free

energy still unrealized, committed suicide. One year before Hendershot’s death, a book,

The Sea of Energy in Which the Earth

Floats, was privately printed in Salt Lake City by its author,

T.

Henry Moray, Doctor of Electrical Engineering, who had earned his

degree at the University of Uppsala in Sweden while on a stint as a

missionary for the Mormon Church.

The book was Moray’s account of a nearly fifty-year-long, apparently

successful effort to develop yet another collector of atmospheric

energy.

The inventor states that he took first

inspiration from a statement made by Tesla in an 1892 lecture:

Ere many generations pass, our

machinery win be driven by a power obtainable at any point of

the universe. Throughout space there is energy. Is this energy

static or kinetic? If static, our hopes are in vain; if

kinetic - and this we know it is, for certain - then it is a mere

question of time when men win succeed in attaching their

machinery to the very wheelwork of nature.

By the fall of 1910 Moray had collected

sufficient power to operate small electrical devices which he

demonstrated to friends. It was only after pursuing static energy

for more than a year, however, that he finally came to agree with

Tesla’s statement.

In his own words:

It was during the Christmas holidays

of 1911 that I began to realize the fact that the energy I was

working with was not of a static nature but of an oscillating

nature, and that the energy was not coming out of the Earth but

that it rather was coming in to the Earth from some outside

source.

As principal owner of a Salt Lake

electric company, Moray built, during the 1920s and 1930s, a number

of radiant energy devices, the parts for each one cannibalized from

its predecessor and supplemented with new components.

It was during the second term of

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt that Moray, now become chief

consulting engineer for the western branch of the Rural

Electrification Agency, finally completed an instrument which,

though it weighed only slightly over 55 pounds, could deliver up to

50,000 watts.

The new device so contravened the belief structures and training of

Moray’s fellow REA engineers that one of them, angered by Moray’s

assertion that he was obtaining energy straight from outer space,

took a sledgehammer to the invention and smashed it to pieces. It

has been estimated that its reconstruction would today cost over a

million dollars.

Before its untimely demise, the Moray

invention was said to have lit up a bank of thirty-five light bulbs

with bright, cold light. Precisely how - or even whether - it really

worked may never be known. However, in his book, Moray sandwiches

into a long treatise on cosmic processes involved in the operation

of his collector the claim that his early invention of a solid-state

component - a type of valve, forerunner of the transistor - was the

real key to its functioning. He also submitted that the energy

collecting activity of his generator was initiated by stroking its

first stage for a minute or so with a magnet to produce

oscillations.

What happened subsequently, Moray put

forward - not entirely lucidly - in a lecture at Valley State

College in Northridge, California, on 23 January 1962:

“The circuit is then balanced

through synchronization until the oscillations are sustained by

harmonic coupling with the energies of the universe. The

reinforcing action of the harmonic coupling increases the

amplitude of the oscillations until the peak pulses ‘spill’ over

into the next stage through special detectors of valves which

then prevent the return or feedback of the energy from the

preceding stages.

These oscillating pulsations drive each

succeeding stage which oscillate at a controlled frequency and

which are again reinforced by harmonic coupling with the ever-present energies of the Cosmos. “

The device could also be set going with

power from an electric battery, but according to Moray’s son, John,

his father eschewed its use in demonstrations in favor of the magnet

so that witnesses could not say afterwards - as they did about

Hendershot’s motor - that the invention was basically battery

operated.

It is strange that witnesses have testified that both Hendershot’s

and Moray’s inventions would work only with the inventors present.

The ONR proposal noted that of many working models of Hendershot’s

motor built over thirty-five years, none gave sufficient performance

“without the hand of Hendershot.”

This statement was corroborated by Charles Fort, an original who

spent his life collecting and collating unusual data by combing

reports in several hundred newspapers on a day-to-day basis; in his

book Wild Talents Fort suggests that Hendershot might have possessed

some power of mind over matter which caused the motor to run only

when he was there to affect it.

The fact that Hendershot’s motor

operated at Selfridge Field only when oriented north-south by not

east-west also seems to suggest that it may have been related in its

underlying principle to Wilhelm Reich’s motor, said to draw power

from a non-electrical energy called “orgone” which permeates the

atmosphere above and rotates in an east-west direction around the

earth. Whatever the case, since Hendershot’s time, Fort’s “wild

talents” have now invaded the scientific laboratories of several

countries where physicists have proved the ability of certain

individuals to affect matter in as yet totally inexplicable manner.

Despite protests made by professional

magicians claiming that his feats are only sleight of hand, the

Israeli Uri Geller has astounded scientific observers by bending

metal at a distance. In controlled experiments throughout the world,

a number of children have recently succeeded in equaling, and even

surpassing, Geller’s psychokinetic exploits.

A book is now on its way to the

publisher detailing the scope of what may lead to a Copernican

revolution in science.

Late twentieth-century technology has not yet followed up on the

trails blazed by Tesla, Hubbard, Hendershot, and

Moray. It is not

difficult to realize the havoc these inventors would have caused had

they been put into operation at the time of their appearance. If

“fuelless” power had been widely available in the first decades or

even in the middle of this century, whole industries involving

massive amounts of capital and employing thousands of workers might

have gone under.

In the last quarter of the century it

may be that, in the face of mounting costs for oil and uncertainty

about the side effects of atomic power plants, new efforts will be

made to probe behind the curtain with which Tesla so ingeniously

surrounded himself. Federal officials in Canada are presently

studying some aspects of Tesla’s power transmission system in the

hope of obviating the construction of expensive transmission lines

designed to carry hydroelectric power developed in the country’s

northern regions to the large urban centers concentrated in the

south.

They are also considering Tesla’s

charged particle collector as a way of furnishing electricity to

Canada’s remote Arctic regions, small prairie communities, and

individual homes and factories. The potential of energy obtainable

from Canadian waterfalls and rivers is so great that there is also

the possibility of adapting the Tesla system to export energy to

energy-short underdeveloped countries anywhere on earth.

A mystery shrouded the last thirty years of Tesla’s life.

Reports leaking out on his Colorado experiments spurred J. Pierpont

Morgan to put up money to finance similar work in the East. In 1901

Tesla began erecting a new experimental station on two hundred acres

of Long Island land, donated by Morgan’s fellow banker, James

Warden. The Wardencliff development, almost an exact duplicate of

the Pike’s Peak installation, was to be the fulfillment of Tesla’s

dream of creating the hub for a “city beautiful.”

When completed in 1905, the station was

closed. It seems that Tesla, who had ignored practical monetary

matters all his life, had consumed the entire sum made available by

Morgan for the station’s construction. Operating the laboratory

would have required another large donation, not forthcoming.

Though chosen to share the 1912 Nobel

Prize in Physics with Edison, Tesla refused it. The Nobel Committee,

perhaps angered at this slight, turned its back on America and

finally awarded the prize to the Swedish physicist Gustav Dalen.

In

Prodigal Genius, a biography

of Tesla, John J. O’Neill speculated on Tesla’s motive for

turning down the honor:

Tesla made a very definite

distinction between the inventor of useful appliances and the

discoverer of new principles... a pioneer who opens up new

fields of knowledge into which thousands of inventors flock to

make commercial applications of the newly revealed information.

Tesla declared himself discoverer and Edison an inventor; and he

held the view that placing the two in the same category would

completely destroy all sense of the relative value of the two

accomplishments.

From this point on, Tesla’s life

presents a picture of steadily dwindling energy, though in the 1920s

he still had enough forward motion to patent a helicopter-like flying

machine and develop an advanced steam turbine.

Legal recognition for his pioneer work in wireless radio

transmission came only one year before his death, when the United

States Supreme Court wrote an opinion that several important

features of Guglielmo Marconi’s invention, for which he was awarded

the Nobel Prize in 1909, had been anticipated by Tesla.

As recently as January 1976, at a Tesla

Symposium held by the Institute for Electronic and Electrical

Engineers in New York’s Statler Hilton Hotel, J. Roland Morin, Chief

Engineer for Large Lamps at Sylvania GTE International, announced

that industrial firms are now reinvestigating Tesla’s concept for electrodeless discharge lamps inductively coupled to a

high-frequency power supply, developed way back in the 1880s but

overshadowed by Edison’s achievement.

What accounted for Tesla’s decline?

The only explanation given was based on

a story told by the inventor to his biographer, O’Neill, who

characterized it as “without parallel in human annals.” O’Neill had

noticed that Tesla, poverty-stricken and lonely, spent hours feeding

pigeons which he would call from under the Gothic tracery of St.

Patrick’s Cathedral and eaves of the New York Public Library.

What,

asked O’Neill, was his fascination with the birds?

‘I have been feeding pigeons,

thousands of them, for years, ‘ replied Tesla, ‘but there was

one pigeon, a beautiful bird, pure white with light gray tips on

its wings. That one was different... No matter where I was

that pigeon would find me; when I wanted her I had only to wish

and call her and she would come flying to me... I loved that

pigeon... I loved her as a man loves a woman, and she loved

me.

‘Then one night as I was lying in my bed in the dark, solving

problems, as usual, she flew in through the open window and

stood on my desk. I knew she wanted me; she wanted to tell me

something important, so I got up and went to her. As I looked at

her I knew she wanted to tell me - she was dying. And then, as I got her message,

there came a light from her eyes - powerful beams of light...

a light more intense than I had ever produced by the most

powerful lamps in my laboratory.

‘When that pigeon died,

something went out of my life. Up to that time I knew with a

certainty that I would complete my work, no matter how ambitious

my program, but when that something went out of my life I knew

my life’s work was finished.’

Tesla’s “World System of Wireless

Transmission” as summarized in his article “The

Problem of Increasing Human Energy - With Special References to The

Harnessing of The Sun's Energy"

through the Use of the Sun’s Energy”

(Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, June 1900):

The World System has resulted from a

combination of several original discoveries made by the inventor

in the course of long-continued research and experimentation. It

makes possible not only the instantaneous and precise wireless

transmission of any kind of signals, messages, or characters, to

all parts of the world, but also the interconnection of the

existing telegraph, telephone, and other signal stations without

any change in their present equipment.

By its means, for instance, a

telephone subscriber here may call up and talk to any other

subscriber on the globe. An inexpensive receiver, no bigger than

a watch, will enable him to listen anywhere, on land or sea, to

a speech delivered or music played in some other place, however

distant.

The World System is based on the

application of certain important inventions and discoveries,

including:

-

The Tesla Transformer. This

apparatus is in the production of electrical vibrations as

revolutionary as gunpowder in warfare.

-

The Magnifying Transmitter. This

is Tesla’s best invention - peculiar transformer specially

adapted to excite the Earth, which is in the transmission of

electrical energy what the telescope is in astronomical

observation.

-

The Wireless System. This system

comprises a number of improvements and is the only means

known for transmitting economically electrical energy to a

distance without wires

The first World System power plant

can be put in operation in nine months. With this power plant it

will be practicable to attain electrical activities up to 10

million horsepower (25 billion watts), and it is designed to

serve for as many technical achievements as are possible without

undue expense.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aug, Stephen. “Who’s Fouling Up

Global Radio?” Washington Star, 29 October 1976, pp. 1, 4.

Detroit Free Press. Lester Hendershot stories: 25, 26, 28, 29

February 1928; 8, 9, 12 March 1928; 11 November 1962.

Korac, Veljko. “The Inventions and Inspiration of Nikola Tesla.”

Paper read at the International Electronic and Electrical

Engineers Nikola Tesla Symposium, 30 January 1976, New York

City. Moray, T. Henry. The Sea of Energy in Which the Earth

Floats. The Research Institute, Inc., 2505 South Fourth East,

Salt Lake City, Utah 84115.

____. “Speech Given by T. Henry Moray, January 23, 1962, 8:00

P.M. in the Speech-Drama Building, Valley State College,

Northridge, California.”

Morin, J.F. “Light Sources - Past, Present, and Future.” Paper

read at the International Electronic and Electrical Engineers

Nikola Tesla Symposium, 30 January 1976, New York City. New York

Times. Lester Hendershot stories: 27, 28 February 1928.

O’Neill, John J. Prodigal Genius: The Life of Nikola Tesla. Ives

Washburn Inc., 1944. Puharich, Andrija. “The Work of Nikola

Tesla Ca. 1900 and Its Relationship to Physics, Bioenergy and

Healing.” Paper read at the International Interdisciplinary

Conference on Consciousness and Healing, 13 October 1976,

University of Toronto. Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Lester

Hendershot stories: 25, 27 February 1928. Alfred Hubbard

stories: 17 December 1919; 1 February 1920, 29 July 1920; 27

February 1928- 16 July 1973; 23 March 1975.

Shunaman, Fred.”12-Million Volts.” Radio Electronics, June 1976,

pp. Tesla, Nikola. Correspondence, Columbia University Library,

Special Collections, Manuscript Section.

____. “My Inventions.” Electrical Experimenter, February-June

1919. ____. Lectures, Patents, and Articles. Nikola Tesla

Museum, Belgrade 1956; reprinted by Health Research, (Mokelumme

Hill, Calif. 95245), 1973.

____. “A Machine to End War.” Liberty, 9 February 1935, pp. 5-7.

____. “Talking with the Planets. “Collier’s, 9 Feburary 1901,

pp. 64-65 , Seymour.

“Electricity and Weather Modification,” IEEE Spectrum April

1969, pp. 26ff.

United States Reports, vol. 320, Cases Adjudged in the Supreme

Court at October Term 1 942

and October Term 1943, “Marconi Wireless Co. v. U. S.,” pp.

1-80.

|