PTARMIGAN.

Birds found in great numbers in the Arctic Circle.

One of the principal proofs that the earth is hollow, is that it is warmer near the poles. If this be so, to what are we to attribute the heat? Nothing, however, has been found to produce heat near the poles to make it warmer. If it can be shown--by quoting those who made the farthest advance toward the supposed poles--that it is warmer, that vegetation shows more life, that game is more plentiful than farther south, then we have a reasonable right to claim that the heat comes from the interior of the earth, as that seems to be the only place from which it could come. In presenting the reports of those best able to judge, very little comment will be made, as the reader should form his own opinions.

In "Captain Hall's Last Trip," page 166, is read: "We find this a much warmer

country than we expected. From Cape Alexander the mountains on either side of the Kennedy Channel and Robeson's Strait we found entirely bare of snow and ice, with the exception of a glacier that we saw covering, about latitude 80 deg. 30 min., east side the strait, and extending east-northeast direction as far as can be seen from the mountains by Polaris Bay.

"We have found that the country abounds with life, and seals, game, geese, ducks, musk-cattle, rabbits, wolves, foxes, bears, partridges, lemmings, etc. Our sealers have shot two seals in the open water while at this encampment. Our long Arctic night commenced October 13th, having seen only the upper limb of the sun above the glacier at meridian October 12th."

Nansen draws special attention to the warmth, for he says: "Fancy, only 12 deg. (21½ deg. Fahr.) of frost in the middle of December! We might almost imagine ourselves at home--forget that we were in a land of snow to the north of the eighty-first parallel."

This was at one of the farthest points north reached by anyone, only in a different direction; and yet the weather was mild and pleasant.

Peary also makes mention of the higher

PTARMIGAN.

Birds found in great numbers in the Arctic Circle.

temperature. On pages 214 and 215, he says: "I expected to hear later of our February fohn in other parts of Greenland, and I was not disappointed. Lieutenant Ryder was living for nine months at Scoresby Sound, on the coast of East

[paragraph continues] Greenland, while we were at McCormick Bay. He was about four hundred and fifty geographical miles south of us. The maximum temperatures he recorded occurred in February and May. He says (Petermann's Mittheilungen, XI, 1892, page 256) that these high temperatures were clue to severe fohn storms, one of which, in February (date not given), suddenly raised the thermometer to 50 deg. F., 8½ deg. higher than my instrument had recorded."

It will be observed that these extremely strong winds from the interior of the earth, not only raise the temperature considerably in the vicinity of the Arctic Ocean, but affect it very materially four hundred and fifty miles away. Nothing could raise the temperature in such a manner, except a storm coming from the interior of the earth.

Nansen, in his second volume, page 355, tells us: "This island we came to seemed to me to be one of the most lovely spots on the face of the earth. A beautiful flat beach, an old strand lined with shells

strewn about, a narrow belt of clear water along shore, where snails and sea urchins (Echinus) were visible at the bottom and amphipoda were swimming about. In the cliffs overhead were hundreds of screaming little auks, and beside us the snow-buntings fluttered from stone to stone with their cheerful twitter. Suddenly the sun burst forth through the light, fleecy clouds, and the day seemed to be all sunshine. Here was life and fair land; we were no longer on the eternal drift-ice! At the bottom of the sea just beyond the beach I could see whole forests of seaweed (Laminaria and Fucus) . Under the cliffs here and there were drifts of beautiful rose-colored snow."

When one takes into account Nansen's description of this island, and connects that with the fact that no one has been able to reach the pole, notwithstanding that the travelers keep going where it is warmer, where there is more life, less ice, and but little snow, yet they make no progress that leads them to the much-sought goal, this is one of the strongest

arguments that there is no such place. The farther the explorers pass into the interior of the earth, the warmer it will be found; and when they succeed in passing the belt of country that has so much fog, snow, and clouds, and drift-ice coming up from the interior, they will find plain sailing and comfortable weather, but they will never reach the pole. Whoever spends his time and strength looking for the poles will be like a young doctor in Illinois. Some one told him that the milk-sickness was very bad in a certain county in that State, and he, not having much practice, thought he would like to try his hand at curing it. He started for the county where it was reported to be the worst, but when he got there he was told that there was no milk-sickness in that county, but it was quite bad in the county adjoining. So he traveled on, and when he got there, they told him the same story. After chasing the phantom for a while, he returned, and reported that it was harmless, as no disease need be feared when no one could get nearer to it than the county adjoining.

That is much nearer than explorers will ever get to the poles.

On one of Greely's farthest trips north--of which he gives an account on page 73--he speaks of the vegetation: "This creek was of moderate size, and drained a valley of considerable extent, which extended to the northwestward. The vegetation seemed more abundant than at Cape Hawks, and eight varieties of flowers were gathered during our brief stay, but the general appearance was of desolation."

This shows that it was getting warmer.

Again, on the same trip out from camp to explore the surroundings, he speaks of a large flock of eider-ducks that had settled in an open pool, and to the north, three-quarters of a mile, ten musk-oxen were quietly grazing; the sloping hills were covered with vegetation, flowers, the familiar buttercup, and countless Arctic poppies of luxuriant growth. "Surely this presence of birds and flowers and beasts was a greeting on nature's part to our new home."

Does that sound as if he had expected to

find these things there, or that their presence was an everyday occurrence? No: it is the tone of surprise.

From what place had those birds and

EIDER-DUCKS.

Found in great numbers in the Arctic Circle.

game come? South of them for many miles the earth is covered with a perpetual snow--in many locations thousands of feet deep. They are found in that location in summer; and as it is warmer farther north,

they would not be likely to go to a colder climate in winter. They seem to pass into the interior of the earth, or as far as suits their nature. Let me state here that the mutton-birds of Australia leave that continent in September, and no one has ever been able to find out where they go. My theory is that they pass into the interior of the earth, via the South Pole.

Greely says again, on page 264: "While we were at this camp, Private Connell visited the mouth of the valley running to the northwest. He found vegetation to be abundant, and reported that during the summer months a river evidently flows into the bay from the valley. At that point he also noted four wolves, and with them a musk-ox, the first of the season. Leading to the valley, he also found what appeared to be a musk-ox trail (similar to the buffalo trails of the 'Far West'), which indicated plainly the valley was a winter resort for these animals."

As they proceeded farther north, where no white man had ever trod, they found the trails of musk-ox, showing that those animals

made it their winter abode. Remember, they had traveled hundreds of miles without meeting any signs of life.

"As we were about entering camp, a dark-colored bird, about the size of a plover, flew swiftly by us from behind, and disappeared. It was neither snow-bunting nor ptarmigan, as all agreed. Wolf, fox, lemming, hare, musk-ox, and ptarmigan tracks were all seen during the day." (Page 276.)

On page 330, he says: "This camp proved prolific in animal life, thus indicating a luxuriant vegetation near. Two ptarmigan were flying around, a hare was captured, and traces of foxes and lemmings were observed. Tracks of a passing bear, going to the northeast, were seen on the ice-foot, and abundant traces of musk-oxen were discovered, proving that these animals frequent this place in considerable numbers, though the indications were not of recent date."

"Sergeant Brainard, who had charge of the fresh meat, records that up to this date fifty-two musk-oxen had been obtained in

[paragraph continues] 1882, averaging two hundred and forty-three pounds each of dressed meat." (Page 422.)

"Long returned at 6 p. m., having been gone twenty-two hours hunting. His pro-longed absence caused much alarm, as he was alone. Several parties had been sent out to search for him, when he was met returning. He had fallen in with a herd of musk-oxen in the valley, about two miles above the head of St. Patrick Bay. He had sixteen rounds of ammunition at starting, and, shortly after, fired two at an owl. With the remaining ammunition he killed eight musk-oxen, and wounded two others; four escaped. He had delayed to skin the eight before returning to the station, in order that the meat should not taint. He saw three large falcons, the first that had been observed by us."

The skinning of the musk-oxen by Long, to prevent tainting of the flesh, would naturally suggest unusually warm weather to the reader. While the weather was warm, that was not the only reason why the animals were immediately

skinned. If the musk-ox is left any length of time after death with the skin on, the meat becomes tainted, regardless of weather conditions.

Where could one go and find such abundance of game as at the farthest point north reached? The game is found there in summer. Can anyone tell where it goes in winter? Greenland is covered with snow from one to ten thousand feet deep. (Vide Peary's report of his trip to the Arctic overland.) If the game be found at the extreme northerly points in summer, is it reasonable to suppose it would migrate to a colder climate in winter? It would be better to stay where it is. Greely tells us that the trails indicate that the musk-oxen make their winter quarters there. Since it becomes warmer as they go north, instinct tells them not to go south in winter. And if they do not go south, they must go into the interior of the earth.

Nansen (Vol. II, page 75) gives us a description of the conditions that obtained, from which one can judge of the warmth

of the weather: "I cannot help believing that a land which, even in April, teems with bears, auks, and black guillemots, and where seals are basking on the ice, must be a Canaan, flowing with milk and honey,

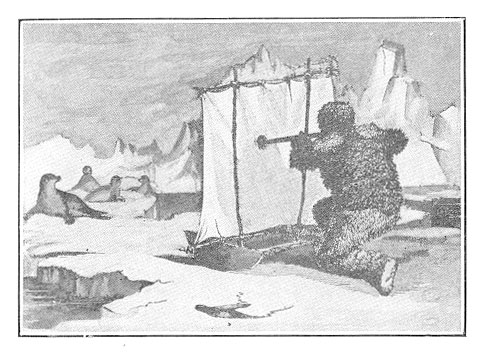

SHOOTING SEALS.

How natives slaughter seals in the Arctic Circle.

for two men who have good rifles and good eyes; it must surely yield food enough not only for the needs of the moment, but also provisions for the journey onward to Spitzbergen."

This was Nansen's remark when he was about to leave the Fram, after he had drifted nearly five months in an ice-floe.

In the same volume, page 346, he gives additional evidence as to weather and warmth. "It is a curious sensation to paddle in the mist, as we are doing, without being able to see a mile in front of us. The land we found we have left behind us. We are always in hopes of clear weather, in order to see where the land lies in front of us--for land there must be. This flat, unbroken ice must be attached to land of some kind; but clear weather we are not to have, it appears. Mist without ceasing; we must push on as it is."

The mist, fog, and clouds spoken of as so prevalent, should be accounted for by something different than plain Arctic Ocean. The best explanation seems that warm air comes from the interior of the earth (where the atmosphere is wholly different), and when it passes out in winter produces mist, fog, or cloud; but more generally snow, summer or winter.

Nansen, in Volume II, page 354, says: "As I mentioned before (August 13), had at first supposed the sound on our west to be Rawlinson's Sound, but this now appears impossible, as there was nothing to be seen of Dove Glacier, by which it is bounded on one side. If this was now our position, we must have traversed the glacier and Wilczek Land without noticing any trace of either; for we have traveled westward a good half degree south of Cape Buda-Pesth. The possibility that we could be in this region we consequently now hold to be finally excluded. We must have come to a new land in the western part of Franz Josef Land, or Archipelago, and so far west that we had seen nothing of the countries discovered by Payer. But so far west that we had not even seen anything of Oscar's Land, which ought to be situated in 82 deg. North and 52 East. This was indeed incomprehensible; but was there any other explanation?"

And this is Nansen's experience after traveling and drifting more than a year on floating ice, when he undoubtedly passed farther into the interior than any explorer,

although he himself did not know where he was.

Schwatka speaks of the game in the Arctic region. After reading, the reader will naturally ask where it goes during the winter. Some say that it goes south; but where does it stop? I know of no place where such an amount of game goes in winter. Most of the game that Schwatka mentions is certainly not at all common to any location I can think of; or, if so, the number must he limited. I am quite sure that the game passes into the interior of the earth, as many of the birds are heavy, and not built for long journeys.

"In no place in the world," says Schwatka, "is aquatic life so abundant as in the polar regions during the summer. The instance I have given of the eiders in Terror Bay is but one of many constantly encountered in polar literature. 'The little auks or rotges,' says a writer who has been in Spitzbergen, 'are so numerous that I have frequently seen an uninterrupted line of them extending to a distance of more than three miles, and so close together

A SWARM OF AUKS.

These birds are found so plentiful in the Arctic regions that when they fly overhead they darken the skies, their little voices being often heard from a distance of four or five miles.

that thirty have fallen at one shot.' This living column might be about six yards broad and as many deep, so that, allowing sixteen birds to the cubic yard, there would be four millions of these little creatures on the wing at one time. This number may appear greatly exaggerated, but when we are told that these auks congregate in such swarms as to darken the air like a passing cloud, and that their chorus is heard distinctly at a distance of four or five miles, these numbers do not appear so great. The dovekies are the most numerous of the summer ducks in the northern part of the bay, and they are especially thick about Depot Island, whose Innuit name is Pikkeulik, meaning the island of birds' nests, and where the dovekies deposit their greenish, blotched eggs in innumerable quantities."

Kane narrates, page 301, that "after traveling due north over a solid area choked with bergs and frozen fields, Morton was startled by the growing weakness of the ice, its surface becoming rotten, and the snow wet and pulpy. His dogs, seized

with terror, refused to advance. Then for the first time the fact broke upon him that a long, dark band seen to the north beyond a protruding cape--Cape Andrew Jackson--was water. With danger and difficulty he retraced his steps and, reaching sound ice, made good his landing on a new coast."

On page 302 Kane adds: "From the southernmost ice, seen by Dr. Hayes only a few weeks before, to the region of this mysterious water was, as the crow flies, one hundred and six miles. But for the unusual sight of birds and the unmistakable giving way of the ice beneath them they would not believe in the evidence of eyesight. Neither Hans nor Morton was prepared for it. Landing on the cape, and continuing their exploration, new phenomena broke upon them. They were on the shores of a channel, so open that a frigate, or a fleet of frigates, might have sailed up it. As they traveled north, this channel expanded into an iceless area; for four or five small pieces--lumps --were all that could be seen over the entire

surface of its whitecapped waters. Viewed from the cliffs, and taking thirty-six miles as the mean radius open to re-liable survey, this sea had a justly estimated extent of more than four thousand square miles."

In the above excerpt, Kane speaks of traveling one hundred and six miles due north, over solid ice, to open water, and finding it filled with all kinds of game, of which there had been no sign one hundred and six miles farther south. How is this accounted for on the theory that the earth is solid? If it was becoming warmer, what made it so? If the winds, blowing in from a still colder climate, would produce a warm atmosphere, then all I have to say is that Nature operates differently at the poles than elsewhere on earth. A hot breeze cannot blow off an iceberg any more than a cold breeze can belch out of a red-hot furnace. The fact is, the earth being hollow, the air passes out of the interior of the earth; hence the interior atmosphere is necessarily warmer.