|

del Sitio Web

Wikipedia

La base del calendario maya, según algunos, está en culturas más

antiguas como la

Olmeca; para otros, el origen es propio de la

civilización maya; dado que es similar al calendario mexica, se

considera una evidencia de que en toda Meso-américa utilizaban el

mismo sistema calendárico.

El calendario maya consiste en dos

diferentes clases conocidas como cuentas de tiempo que transcurren

simultáneamente: el Sagrado, Tzolkin o Bucxok de 260 días, el Civil,

Haab, de 365 días y la cuenta larga.

El calendario maya es cíclico, porque se repite cada 52 años mayas.

En la cuenta larga, el tiempo de cómputo comienza el 0.0.0.0.0 4

ahau 8 cumkú que sería el 13 de agosto del 3.114 a. C. en el

calendario gregoriano y terminará el

21 de diciembre de 2012.

La casta sacerdotal maya, llamada Ah Kin, era poseedora de

conocimientos matemáticos y astronómicos que interpretaba de acuerdo

a su cosmovisión religiosa, los años que iniciaban, los venideros y

el destino del hombre.

Descripción

Es un calendario de 260 días Tzolkin, que tiene 20 meses (kines)

combinados con trece numerales (guarismos). El Tzolkín se combinaba

con el calendario Haab de 365 días (kines) de 18 meses (uinales) de

20 días (kines) cada uno y cinco días adicionales Uayeb, para formar

un ciclo sincronizado que duraba 52 tunes o Haabs, 18.980 kines (días).

La cuenta larga era utilizada para distinguir cuándo ocurrió un

evento con respecto a otro evento del tzolkín y haab. El sistema es

básicamente vigesimal (base 20), y cada unidad representa un

múltiplo de 20, dependiendo de su posición de derecha a izquierda en

el número, con la importante excepción de la segunda posición, que

representa 18 x 20, o 360 días.

Algunas inscripciones mayas de la cuenta larga están suplementadas

por lo que se llama Serie Lunar, otra forma del calendario que

provee información de la fase lunar.

Otra forma de medir los tiempos era medir ciclos solares como

equinoccios y solsticios, ciclos venusianos que dan seguimiento a

las apariciones y conjunciones de Venus al inicio de la mañana y la

noche. Muchos eventos en este ciclo eran considerados adversos y

malignos, y ocasionalmente se coordinaban las guerras para que

coincidieran con fases de este ciclo.

Los ciclos se relacionan con diferentes dioses y eventos cósmicos.

Es así como el Quinto Sol representa el final del ciclo estelar

asociado a la luna y el inicio del periodo conocido como El sexto

sol asociado al regreso de Kukulkan como nuevo Mesías.

El Sistema Tzolkin

El Tzolkin ("la cuenta de los días"), de 260 días, es único en el

mundo.

Si bien se ha sugerido que está relacionado con la duración

de la gestación humana, otros lo relacionan con Venus, y era usado

para celebrar ceremonias religiosas, pronosticar la llegada y

duración del período de lluvias, además de períodos de cacería y

pesca, y también para pronosticar el destino de las personas.

Cuenta el tiempo en ciclos de trece meses de veinte días cada uno.

Llamaban a sus días y meses con los nombres de varias deidades.

Ordenados sucesivamente, los nombres de los días solares y los meses

en maya yucateco son:

|

Número |

Días solares (kin) |

Meses (uinal) |

|

1 |

Imix |

Pop |

|

2 |

Ik |

Uo |

|

3 |

Ak'bal |

Zip |

|

4 |

K'an |

Zotz |

|

5 |

Chikchan |

Tzecos |

|

6 |

Kimi |

Xul |

|

7 |

Manik |

Yax kin |

|

8 |

Lamat |

Mol |

|

9 |

Muluk |

Chen |

|

10 |

Ok |

Yax |

|

11 |

Chuen |

Zac |

|

12 |

Eb |

Ceh |

|

13 |

Ben |

Mac |

|

14 |

Ix |

Kan kin |

|

15 |

Men |

Moan |

|

16 |

Kib |

Pax |

|

17 |

Kaban |

Kayab |

|

18 |

Etz'nab |

Cumkú |

|

19 |

Kawak |

Uayeb |

|

20 |

Ajau |

|

|

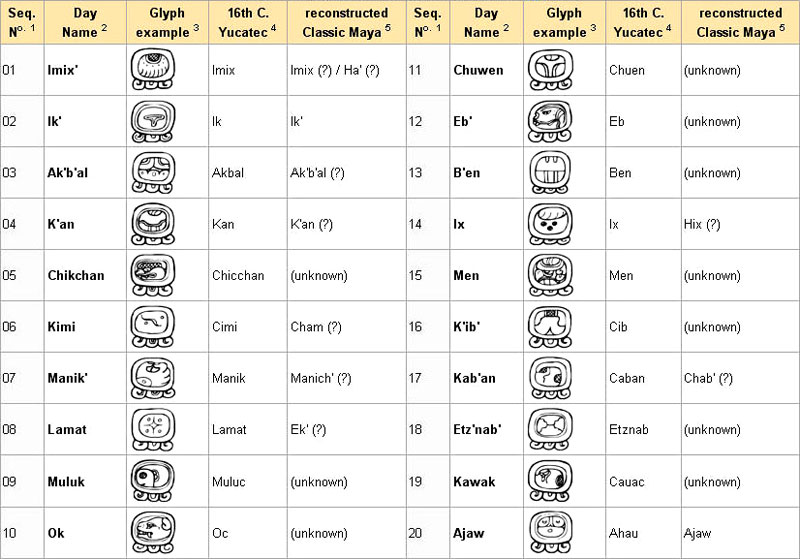

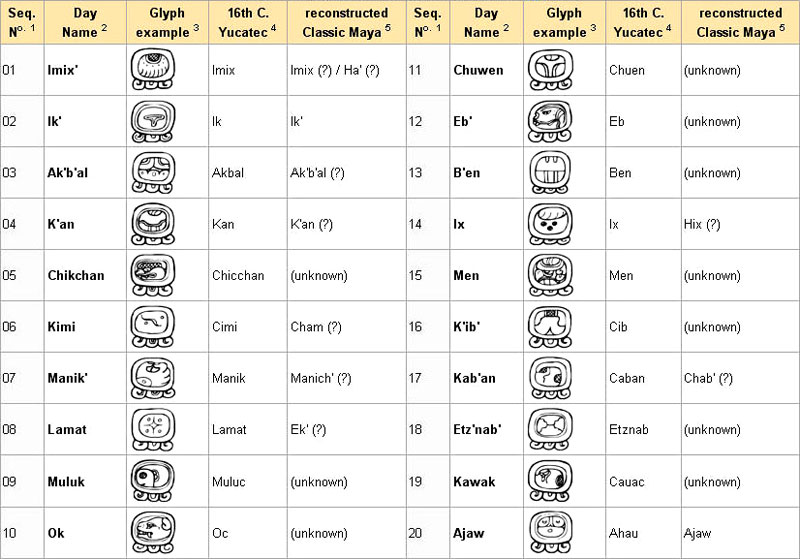

Adicionalmente, cada uno de los nombres de los días del calendario

sagrado maya es asociado con un glifo de manera única según esta

otra tabla:

NOTAS:

1. Número de secuencia del día en el calendario Tzolk'in.

2. Nombre del día, en la ortografía estándar y revisada de la

Academia de Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala.

3. Un glifo de ejemplo para el día mencionado. Para la mayoría de

estos casos se han registrado diferentes formas; las que se muestran

son típicas de las inscripciones de los monumentos hallados.

4. Nombre del día, como fue registrado desde el siglo XVI por

estudiosos como Diego de Landa; esta ortografía ha sido (hasta ahora)

ampliamente usada.

5. En la mayoría de los casos, el nombre del día es desconocido,

como se indicaba en el tiempo del Período Clásico Maya cuando se

hicieron tales inscripciones. La versiones que aparecen en la tabla

en lenguaje Maya, fueron reconstruidas basándose en evidencia

fonológica, si estuviera disponible. El símbolo '¿?' indica que la

reconstrucción es tentativa.

El Sistema Haab

El Haab mide el año solar dividiéndolo en 18 meses de 20 días cada

uno, pero los últimos 5 días del año, llamados "Uayeb", no tienen

nombre, se consideraban nefastos, vacacionales y excluidos de los

registros cronológicos, aunque eran fechados. El primer día de cada

mes se representaba con el signo cero, debido a que era el momento

inicial en que comenzaba a regir ese mes.

El haab era la base del calendario religioso colectivo; marcaba los

ritmos comunitarios y muchas veces señalaba las ceremonias en las

que participaban los diferentes especialistas.

Se habla de exactitud en el calendario maya pero realmente no tiene

que ver nada con el calendario gregoriano y no hay evidencias de

correcciones o ajustes.

El Uayeb no es considerado un mes como tal pero así es nombrado al

ciclo de tiempo considerado nefasto, vacacional y excluido de los

registros cronológicos, aunque era fechado.

La cuenta larga o serie inicial

Así como en el calendario gregoriano existen nombres para designar

determinados períodos de tiempo, los mayas tenían nombres

específicos para períodos de acuerdo con su sistema vigesimal

modificado de contar días. La unidad básica de medición del pueblo

maya era el kin o día solar.

Los múltiplos de esta unidad servían para designar diferentes lapsos

de tiempo como sigue:

|

Unidades de

cómputo de la cuenta larga |

|

Nombre maya |

Días |

Equivalencia[1] |

|

kin |

1 |

— |

|

uinal |

20 |

20 kin |

|

tun |

360 |

18 uinal |

|

katún |

7.200 |

20 tun o 360

uinales |

|

baktún |

144.000 |

7.200

uinales, 400 tunes o 20

katunes |

|

Una forma sencilla y estandarizada de representar la notación de los

años mayas en Cuenta Larga se hace con números separados por puntos.

Por tanto, la notación 6.19.19.0.0 es igual a 6 baktunes, 19 katunes,

19 tunes, 0 uinales y 0 kines. El total de días se calcula

multiplicando cada uno de estos números por su equivalente en días

solares de acuerdo a la anterior tabla y sumando los productos

obtenidos.

En este caso particular, el total de días T es:

Los términos de mayor duración siguientes que muy raras veces eran

utilizados por los mayas eran piktún, kalabtún, kinchinltún, y

alautún.

Veinte baktunes formarían un piktún de

aproximadamente 7.890 años y veinte piktunes generan un kalabtun de

57.600.000 kines, aproximadamente 157.810 años. Según el arqueólogoo

John Eric Sidney Thompson, el número maya 0.0.0.0.0 es

equivalente al día juliano número 584.283, es decir, 11 de agosto de

3114 a. C.

Este número es considerada la constante de correlación del

calendario maya, respecto a los calendarios juliano y gregoriano y

se usa en los algoritmos de conversión de fechas en el calendario

maya a los otros dos y viceversa.

La rueda calendárica

Ni el tzolkin, ni el haab numeraban los años.

La combinación de fechas mediante los dos sistemas era suficiente en

la vida práctica ya que una coincidencia de fechas se produce cada

52 años, lo cual rebasaba la expectativa de vida de la época

prehispánica. Los mayas fusionaron estos dos sistemas, en un ciclo

superior llamado "rueda calendárica". La conformación de esta rueda,

que se compone de tres círculos, da por resultado ciclos de 18.980

días, en cada uno de los cuales uno de los 260 días del tzolkin

coincide con otro de los 365 días del Haab.

El círculo más pequeño está conformado por 13 números; el círculo

mediano por los 20 signos de los veinte días mayas del calendario

Tzolkin, y el círculo más grande por el calendario haab con sus 365

días (dieciocho meses de veinte días y el mes corto de cinco días).

En este conteo, los mayas consideraban que el día de la creación fue

el 4 ahau 8 cumkú.

Cada ciclo de 18.980 días equivale a 52 vueltas del haab (calendario

solar de 365 kines) y a 73 vueltas del tzolkin (calendario sagrado

de 260 kines), y al término ambos vuelven al mismo punto. Cada 52

vueltas del haab se celebraba la ceremonia del fuego nuevo,

analógicamente era un "siglo maya".

Los mayas especificaron en una de sus profecías que el momento

exacto del fin del quinto mundo ocurriría cuando la suma de la fecha

marcada se intersecte antes de llegar a medio kin y dé como

resultado el número base para sus cálculos arquitectónicos y

astronómicos.

Festividades religiosas mayas de cada “uinal” o mes maya

Fray Diego de Landa en sus manuscritos conocidos como Relación de

las cosas de Yucatán, describe las festividades religiosas que

celebraban los mayas correspondientes a cada uinal o mes maya,

ceremonias que realizaban de acuerdo a sus creencias para honrar y

complacer a sus dioses:

Para los mayas el uinal Pop, era una especie de año nuevo, era una

fiesta muy celebrada, renovaban todas las cosas de utensilios de

casa, como platos, vasos, banquillos, ropa, mantillas, barrían su

casa y la basura la echaban fuera del pueblo, pero antes de la

fiesta al menos trece días ayunaban y se abstenían de tener sexo, no

comían sal, ni chile, algunas personas ampliaban este período de

abstinencia hasta tres uinales.

Después todos los hombres se reunían

con el sacerdote en el patio del templo y quemaban copal, todos los

presentes ponían un porción de copal en el brasero.[1]

En el uinal Uo se realizaban festividades para sacerdotes,

adivinadores, la ceremonia era llamada Pocam, y oraban quemando

copal a Kinich Ahau Itzamná, a quién consideraban el primer

sacerdote.

Con “agua virgen traída del monte, donde no llegase mujer”

untaban las tablas de los libros y el sacerdote realizaba los

pronósticos del año, realizaban un baile llamado Okotuil.

En el uinal Zip, se juntaban los sacerdotes con sus mujeres, y

usaban idolillos de la diosa Ixchel, y la fiesta se llamaba Ibcil

Ixchel, invocaban a los dioses de la medicina que eran Itzamná,

Citbolontun y Ahau Chamahez, realizaban un baile llamado Chantunyab.

El día siete del uinal Zip día invocaban a los dioses de la caza Ah

Cancum, Zuhuyzib Zipitabai, y otros, cada cazador sacaba una flecha

y una cabeza de venado las cuales eran untadas de betún azul, y

bailaban con las flechas en las manos, se horadaban las orejas,

otros la lengua y pasaban por los agujeros siete hojas de una hierba

llamada Ac..

Al día siguiente era el turno de los pescadores, pero

ellos untaban de betún azul sus aparejos de pesca y no se horadaban

las orejas, sino que se ponían arpones, y bailaban el Chohom, y

después de realizada la ceremonia iban a la costa a pescar, los

dioses eran Abkaknexoi, Abpua, y Ahcitzamalcun.

En Zotz los apicultores comenzaban los preparativos pero celebraban

su fiesta en el uinal siguiente Tzec, los sacerdotes y oficiales

ayunaban, así como algunos voluntarios.

En Zec, no derramaban sangre, los dioses venerados eran los cuatro

bacabs, especialmente Hobnil. Ofrecían a los bacabs platos con

figuras de miel, y los mayas bebían un vino llamado “Balche” el cual

se procesaba de la corteza de un árbol llamado con el mismo nombre (Lonchucarpus

violaceus), los apicultores regalaban miel en abundancia.[2]

En Yaxkin, la ceremonia se llamaba Olob-Zab-Kamyax, se untaban todos

los instrumentos de todos los oficios con betún azul, se juntaban

los niños y las niñas del pueblo y les daban unos golpecillos en los

nudillos, con la idea que los niños fueran expertos en los oficios

de sus padres. Desde este uinal comenzaban a aparejarse para la

ceremonia del uinal Mol

En Xul, era dedicado a Kukulcán, los mayas iban por el jefe supremo

de los guerreros llamado Nacom, al cual sentaban en el templo

quemando copal, realizaban un baile de guerreros llamado Holkanakot,

sacrificando un perro y quebrando ollas llenas de bebida para

terminar su fiesta, y regresar con honores al Nacom a su casa. Esta

ceremonia se celebraba en todos lados hasta la destrucción de

Mayapán, después solo se celebraba en Maní en la jurisdicción de los

Tutul xiúes, todos los señores se juntaban presentaban cinco

banderas de pluma, y se iban al templo de Kukulcán, donde oraban

durante cinco días, después de los cuales bajaba Kukulcán del cielo

y recibía las ofrendas, la fiesta se llamaba Chikabán.

En el uinal Mol, los apicultores oraban a los dioses para que

hubiese buenas flores y de esta manera tener una buena producción de

las abejas,.en este mes era cuando fabricaban las efigies o ídolos

de madera, los cuales eran de alguna forma bendecidos por los

sacerdotes.

Se practicaba un ritual en el cual se sangraban las

orejas.

En cualquiera de los uinales Chen o Yax, hacían una fiesta llamaba

Ocná, que quiere decir “renovación del templo”, la hacían en honor

de los dioses de los maizales; los mayas acostumbraban tener ídolos

de los dioses con pequeños braseros en donde quemaban copal, en esta

fiesta cada año se renovaban los ídolos de barro y sus braseros.

En Zac, el sacerdote y los cazadores hacían una ceremonia para

aplacar a los dioses de la ira, y como una forma de penitencia por

la sangre derramada durante la cazas, (los mayas tenían como “cosa

horrenda” cualquier derramamiento de sangre si dicho derramamiento

no era en sus sacrificios), por eso cuando iban a la caza invocaban

al dios de la caza, le quemaban copal y si podían le untaban al

rostro del ídolo de la caza, la sangre del corazón de la presa.

En las proximidades del inicio del uinal Ceh, existía una fiesta muy

grande y de fecha movible que duraba tres días, con quema de copal,

a la cual Landa llamaba “sahumerías”, ofrendas y borrachera. Los

sacerdotes tenían cuidado de avisar con tiempo para realizar un

ayuno previo.

En Mac, la gente anciana realizaba una ceremonia llamada “Tupp kak”

(matar el fuego), era dirigida a los dioses de los panes y a Itzamná,

en una fogata quemaban corazones de aves y animales, una vez

incinerados los corazones apagaban el fuego con cántaros de agua. Se

juntaba el pueblo y los sacerdotes y untaban con lodo y betún azul

los primeros escalones de las escaleras de sus templos. En esta

fiesta no realizaban ayuno, a excepción del sacerdote.

Diego de Landa no describe ceremonias correspondientes al uinal

Kankin, hasta la fecha se desconocen los dioses que se honraban en

este período del año maya.

En Muan correspondía a los cultivadores de cacao realizar una

ceremonia a los dioses Chac Ek chuah, y Hobnil, sacrificaban un

perro manchado con el color de cacao, y quemaban incienso y ofrecían

iguanas de las azules (probablemente untadas de betún azul) y

ciertas plumas de pájaros, terminada la ceremonia los mayas se

comían las ofrendas.

En Pax, la ceremonia se llamaba Pacum chac, y por un período de

cinco noches se juntaban los señores (batab) y los sacerdotes (ah

kin) de los pueblos menores (batabil), en las capitales y veneraban

a Cit chac cob.

Se homenajeaba con copal al jefe de los guerreros (Nacom)

durante cinco días, realizaban un baile de los guerreros llamado

Holkanakot. El sentido de esta ceremonia era para pedir a sus dioses

alcanzar la victoria frente a sus enemigos. Se sacrificaba un perro,

al cual se le extraía el corazón, se rompían ollas grandes que

contenían bebida, y daban por finalizada la ceremonia, regresando a

sus pueblos.

Durante Kayab y Cumku en cada población hacían fiestas a las cuales

llamaban Zabacilthan, se reunían para presentar ofrendas, comer y

beber preparándose para el Uayeb, el mes corto de los cinco días

nefastos.

Cuando llegaban los cinco días sin nombre conocidos como Uayeb, los

mayas no se bañaban, no hacían obras serviles ó de trabajo, porque

temían que al realizar alguna actividad, les iría mal.[3]

Registros históricos

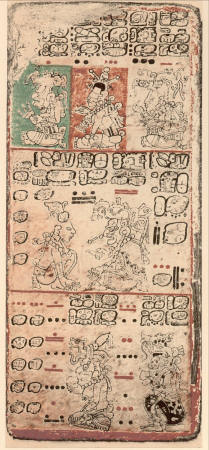

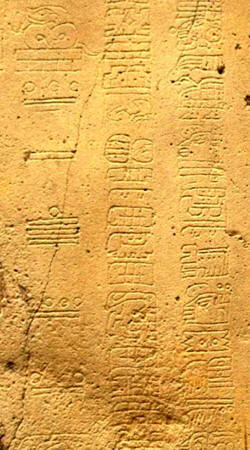

|

|

|

|

Estela maya en Tikal |

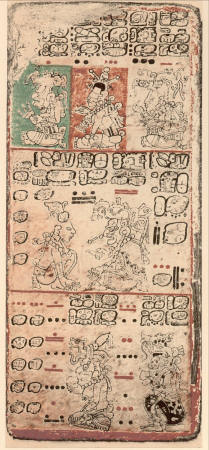

Códice de Dresden |

Los mayas, erigieron estelas para conmemorar fechas de

acontecimientos importantes, los sitios donde mayor número de

estelas se han encontrado son Uaxactún y Tikal; dichas estelas

corresponden al período clásico.

Para los mayas el tiempo era cíclico, de acuerdo a la cuenta de los

katunes (períodos de 20 años), de esta manera profetizaban los

eventos futuros.

Una de las fechas que vaticinaba guerras, conquista

y cambio, era el Katún 8 Ahau, y es la fecha que se describe en el

Chilam Balam de Chumayel, como una fecha crítica para los mayas, en

especial para los Itzáes.

-

En el primer Katún 8 Ahau del 415-435 d.C, los itzáes llegaron a

Bacalar

-

En otro Katún 8 Ahau del 672-692 d.C, los itzáes

abandonaron Chichén Itzá y se fueron a Chakán Putum.

-

En otro Katún 8

Ahau (928-948 d. C.), los itzáes regresan a Chichén Itzá

-

Durante el

siguiente 8 Ahau de 1185-1205 d.C los Cocomes hacen la guerra a los

itzáes, que tienen que huir al Petén Itzá.

-

En otro Katún 8 Ahau

(1441-1461 d. C.) los Tutul xiúes hacen la guerra a los cocomes y

abandonan las grandes ciudades en la península de Yucatán.

-

Finalmente en el 8 Ahau correspondiente 1697-1717 d.C., el último

reducto de los itzáes en Tayasal es conquistado por los españoles.

En el período clásico, las estelas en donde se llevaban los eventos

cronológicos, son sustituidas por códices, que se escribían en

papeles fabricados de la corteza de un árbol parecido a la higuera

llamado "amate".

Desgraciadamente fueron quemados por los misioneros

y frailes quienes consideraban que eran paganos, solo unos cuantos

fueron rescatados.

Después de la conquista, se escribieron manuscritos, donde narraban

los acontecimientos recordados más importantes, se les conoce con el

nombre de Chilam Balam. Sus registros provienen de de la tradición

oral. "Chilam" significa "el que es boca" y "Balam" significa "brujo

o jaguar".

"Chilam Balam" era un sacerdote adivino de Maní, tenía

una gran reputación.

Son varios los manuscritos llamados "Chilam Balam", el más completo

e importante es el de Chumayel. Los manuscritos también incluyen las

"profecías mayas" de acuerdo a la periocidad cíclica del tiempo maya.[4]

Fechas importantes de los mayas

En el período posclásico:

-

10.9.0.0.0 | (2 Ahau 13 Mac), equivale al

15 de agosto de 1007, es fundada Uxmal por Ah Suytok Tutul Xiu.

-

10.10.0.0.0 | (13 Ahau 13 Mol), equivale al 2 de mayo de 1027,

comienza la Liga de Mayapán

-

10.18.10.0.0 | (9 Ahau 13 Uo), equivale al 22 de noviembre de 1194.

el complot de Hunac Ceel, los Cocomes arrojan a los Itzáes de

Chichén Itzá, termina la Liga de Mayapán.

-

10.19.0.0.0 | (8 Ahau 8 Cumhú), equivale al 30 de septiembre de 1204

comienza la hegemonía de Mayapán ayudados por los Ah Canul.

-

11.12.0.0.0 | (8 Ahau 3 Mol), equivale al 6 de enero de 1461, es

destruida la ciudad de Mayapán por los Tutul xiúes, se abandonan

también todas las grandes ciudades.

-

11.13.0.0.0 | (6 Ahau 3 Zíp), equivale al 23 de septiembre de 1480,

se describe un huracán muy fuerte y se registra una peste en la

población.

-

11.15.0.0.0 | (2 Ahau 8 Zac), equivale al 27 de febrero de 1520, ya

han pasado las expediciones de Hernández de Córdoba, Grijalva y

Cortés, se ha producido una epidemia de viruela que ha diezmado a la

población.

-

11.17.0.0.0 | (11 Ahau 8 Pop), equivale al 1 de agosto de 1559,

Francisco de Montejo, su hijo y sobrino han conquistado la península

de Yucatán y han fundado Mérida y Valladolid.

-

12.4.0.0.0 | (10 Ahau 18 Uo), equivale al 27 de julio de 1697,

Tayasal último reducto de los Itzáes es destruida por Martín de

Ursúa.[5]

Algunos Mayas marcan que el

21 de diciembre de 2012 sería el fin del

quinto mundo (uno de los períodos por los que pasa la humanidad), ya

que es el fin de su calendario; esto provocaría un gran cambio en la

humanidad, tal como ocurre al final de cada mundo/período.

Los mayas registraron esta fecha como 13.0.0.0.0.

El calendario en los mayas contemporáneos

El calendario maya que los indígenas utilizan actualmente, aunque

con la misma estructura que el arqueológico, tiene algunas

diferencias importantes en cuanto a fechas. Entre los mayas de

lengua Achi, el año nuevo se festeja entre enero y febrero y los

nombres de los años y meses pueden diferir.

El 10 de enero del 2009,

los Mayas Achí festejaron el año 5196 (de acuerdo con la cuenta

larga), cuyo gobernante es wukub’ kawoq (la séptima tortuga).

Referencias

-

En otras unidades de la

cuenta larga.

-

El copal (pom) es el

incienso maya, resina del árbol del mismo nombre

(protium copal).

-

De acuerdo a la

mitología maya, los bacabs eran los dioses que

sustentaban el cielo para que no se cayese, y habían

escapado cuando el mundo fue destruido por el diluvio,

sus nombres eran Hobnil, Kanalbacab, Kanpauahtun, y

Kanxibchac.

-

Landa, Diego de (1566) Relación de las cosas de

Yucatán (en formato.pdf) - Asociación europea de

mayistas

-

Javier COVO TORRES, Ileana

REYES CAMPOS y Laura MORALES: Las profecías mayas.

México: Dante, 2007. ISBN:970-605-404-9.

The Maya Calendar

from

Wikipedia

Website

The Maya calendar is a system of distinct calendars and almanacs

used by the Maya civilization of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, and by

some modern Maya communities in highland Guatemala.

The essentials of the Maya calendric system are based upon a system

which had been in common use throughout the region, dating back to

at least the 6th century BC.

It shares many aspects with calendars

employed by other earlier Mesoamerican civilizations, such as the Zapotec and Olmec, and contemporary or later ones such as the Mixtec

and Aztec calendars. Although the Mesoamerican calendar did not

originate with the Maya, their subsequent extensions and refinements

of it were the most sophisticated. Along with those of the Aztecs,

the Maya calendars are the best-documented and most completely

understood.

By the Maya mythological tradition, as documented in Colonial

Yucatec accounts and reconstructed from Late Classic and Postclassic

inscriptions, the deity Itzamna is frequently credited with bringing

the knowledge of the calendar system to the ancestral Maya, along

with writing in general and other foundational aspects of Maya

culture.[1]

Overview

The most important of these calendars is the one with a period of

260 days.

This 260-day calendar was prevalent across all

Mesoamerican societies, and is of great antiquity (almost certainly

the oldest of the calendars). It is still used in some regions of

Oaxaca, and by the Maya communities of the Guatemalan highlands. The

Maya version is commonly known to scholars as the Tzolkin, or

Tzolk'in in the revised orthography of the Academia de las Lenguas

Mayas de Guatemala.[2]

The Tzolk'in is combined with another 365-day

calendar (known as the Haab, or Haab' ), to form a synchronized

cycle lasting for 52 Haabs, called the Calendar Round. Smaller

cycles of 13 days (the trecena) and 20 days (the veintena) were

important components of the Tzolk'in and Haab' cycles, respectively.

A different form of calendar was used to track longer periods of

time, and for the inscription of calendar dates (i.e., identifying

when one event occurred in relation to others). This form, known as

the Long Count, is based upon the number of elapsed days since a

mythological starting-point.[3]

According to the correlation between

the Long Count and Western calendars accepted by the great majority

of Maya researchers (known as the GMT correlation), this

starting-point is equivalent to August 11, 3114 BC in the proleptic

Gregorian calendar or 6 September in the Julian calendar (-3113

astronomical).

The Goodman-Martinez-Thompson correlation was chosen

by Thompson in 1935 on the basis of earlier correlations by Joseph

Goodman in 1905 (August 11), Juan Martínez Hernández in 1926 (August

12), and John Eric Sydney Thompson in 1927 (August 13).[4][5]

By its

linear nature, the Long Count was capable of being extended to refer

to any date far into the future (or past). This calendar involved

the use of a positional notation system, in which each position

signified an increasing multiple of the number of days. The Maya

numeral system was essentially vigesimal (i.e., base-20), and each

unit of a given position represented 20 times the unit of the

position which preceded it.

An important exception was made for the

second-order place value, which instead represented 18 × 20, or 360

days, more closely approximating the solar year than would 20 × 20 =

400 days. It should be noted however that the cycles of the Long

Count are independent of the solar year.

Many Maya Long Count inscriptions are supplemented by a Lunar

Series, which provides information on the lunar phase and position

of the Moon in a half-yearly cycle of lunations.

A 584-day Venus cycle was also maintained, which tracked the

heliacal risings of Venus as the morning and evening stars. Many

events in this cycle were seen as being astrologically inauspicious

and baleful, and occasionally warfare was astrologically timed to

coincide with stages in this cycle.

Other, less-prevalent or poorly understood cycles, combinations and

calendar progressions were also tracked. An 819-day count is

attested in a few inscriptions; repeating sets of 9- and 13-day

intervals associated with different groups of deities, animals and

other significant concepts are also known.

Maya concepts of time

With the development of the place-notational Long Count calendar

(believed to have been inherited from other Mesoamerican cultures),

the Maya had an elegant system with which events could be recorded

in a linear relationship to one another, and also with respect to

the calendar ("linear time") itself.

In theory, this system could

readily be extended to delineate any length of time desired, by

simply adding to the number of higher-order place markers used (and

thereby generating an ever-increasing sequence of day-multiples,

each day in the sequence uniquely identified by its Long Count

number).

In practice, most Maya Long Count inscriptions confine

themselves to noting only the first five coefficients in this system

(a b'ak'tun-count), since this was more than adequate to express any

historical or current date (20 b'ak'tuns cover 7,885 solar years).

Even so, example inscriptions exist which noted or implied lengthier

sequences, indicating that the Maya well understood a linear

(past-present-future) conception of time.

However, and in common with other Mesoamerican societies, the

repetition of the various calendric cycles, the natural cycles of

observable phenomena, and the recurrence and renewal of

death-rebirth imagery in their mythological traditions were

important and pervasive influences upon Maya societies. This

conceptual view, in which the "cyclical nature" of time is

highlighted, was a pre-eminent one, and many rituals were concerned

with the completion and re-occurrences of various cycles.

As the

particular calendaric configurations were once again repeated, so

too were the "supernatural" influences with which they were

associated.

Thus it was held that particular calendar configurations

had a specific "character" to them, which would influence events on

days exhibiting that configuration. Divinations could then be made

from the auguries associated with a certain configuration, since

events taking place on some future date would be subject to the same

influences as its corresponding previous cycle dates.

Events and

ceremonies would be timed to coincide with auspicious dates, and

avoid inauspicious ones.[6]

The completion of significant calendar cycles ("period endings"),

such as a k'atun-cycle, were often marked by the erection and

dedication of specific monuments (mostly stela inscriptions, but

sometimes twin-pyramid complexes such as those in Tikal and Yaxha),

commemorating the completion, accompanied by dedicatory ceremonies.

A cyclical interpretation is also noted in Maya creation accounts,

in which the present world and the humans in it were preceded by

other worlds (one to five others, depending on the tradition) which

were fashioned in various forms by the gods, but subsequently

destroyed. The present world also had a tenuous existence, requiring

the supplication and offerings of periodic sacrifice to maintain the

balance of continuing existence.

Similar themes are found in the

creation accounts of other Mesoamerican societies.[7]

Tzolk'in

The tzolk'in (in modern Maya orthography; also commonly written

tzolkin) is the name commonly employed by Mayanist researchers for

the Maya Sacred Round or 260-day calendar.

The word tzolk'in is a

neologism coined in Yucatec Maya, to mean "count of days" (Coe

1992). The various names of this calendar as used by Precolumbian

Maya peoples are still debated by scholars.

The Aztec calendar

equivalent was called Tonalpohualli, in the Nahuatl language.

The tzolk'in calendar combines twenty day names with the thirteen

numbers of the trecena cycle to produce 260 unique days. It is used

to determine the time of religious and ceremonial events and for

divination. Each successive day is numbered from 1 up to 13 and then

starting again at 1.

Separately from this, every day is given a name

in sequence from a list of 20 day names:

NOTES:

1. The sequence number of the named day in the Tzolk'in calendar

2. Day name, in the

standardized and revised orthography of the

Guatemalan Academia de Lenguas Mayas[2]

3. An example glyph (logogram) for the named day. Note that for most

of these several different forms are recorded; the ones shown here

are typical of carved monumental inscriptions (these are "cartouche"

versions)

4. Day name, as recorded from 16th century Yukatek Maya accounts,

principally Diego de Landa; this orthography has (until recently)

been widely used

5. In most cases, the actual day name as spoken in the time of the

Classic Period (ca. 200–900) when most inscriptions were made is not

known. The versions given here (in Classic Maya, the main language

of the inscriptions) are reconstructed on the basis of phonological

evidence, if available; a '?' symbol indicates the reconstruction is

tentative.[8]

Some systems started the count with 1 Imix', followed by 2 Ik', 3

Ak'b'al, etc. up to 13 B'en.

The trecena day numbers then start

again at 1 while the named-day sequence continues onwards, so the

next days in the sequence are 1 Ix, 2 Men, 3 K'ib', 4 Kab'an, 5

Etz'nab', 6 Kawoq, and 7 Ajau. With all twenty named days used,

these now began to repeat the cycle while the number sequence

continues, so the next day after 7 Ajaw is 8 Imix'.

The repetition

of these interlocking 13- and 20-day cycles therefore takes 260 days

to complete (that is, for every possible combination of number/named

day to occur once).

Origin of the Tzolk'in

The exact origin of the Tzolk'in is not known, but there are several

theories. One theory is that the calendar came from mathematical

operations based on the numbers thirteen and twenty, which were

important numbers to the Maya.

The numbers multiplied together equal

260. Another theory is that the 260-day period came from the length

of human pregnancy. This is close to the average number of days

between the first missed menstrual period and birth, unlike Naegele's rule which is 40 weeks (280 days) between the last

menstrual period and birth. It is postulated that midwives

originally developed the calendar to predict babies' expected birth

dates.

A third theory comes from understanding of astronomy, geography and

paleontology. The meso-american calendar probably originated with

the Olmecs, and a settlement existed at Izapa, in southeast Chiapas

Mexico, before 1200 BC.

There, at a latitude of about 15° N, the Sun

passes through zenith twice a year, and there are 260 days between

zenithal passages, and gnomons (used generally for observing the

path of the Sun and in particular zenithal passages), were found at

this and other sites. The sacred almanac may well have been set in

motion on August 13, 1359 BC, in Izapa.

Vincent H. Malmström, a

geographer who suggested this location and date, outlines his

reasons:

-

Astronomically, it lay at the only latitude in North America

where a 260-day interval (the length of the "strange" sacred almanac

used throughout the region in pre-Columbian times) can be measured

between vertical sun positions - an interval which happens to begin

on the 13th of August -- the day the peoples of the Mesoamerica

believed that the present world was created

-

Historically, it

was the only site at this latitude which was old enough to have been

the cradle of the sacred almanac, which at that time (1973) was

thought to date to the 4th or 5th centuries B.C.

-

Geographically, it was the only site along the required parallel of

latitude that lay in a tropical lowland ecological niche where such

creatures as alligators, monkeys, and iguanas were native -- all of

which were used as day-names in the sacred almanac.[9]

Malmström also offers strong arguments against both of the former

explanations.

A fourth theory is that the calendar is based on the crops. From

planting to harvest is approximately 260 days.

|

Name |

Meaning† |

|

Pop |

mat |

|

Wo |

black

conjunction |

|

Sip |

red

conjunction |

|

Sotz' |

bat |

|

Sek |

? |

|

Xul |

dog |

|

Yaxk'in |

new

sun |

|

Mol |

water |

|

Ch'en |

black

storm |

|

Yax |

green

storm |

|

Sak |

white

storm |

|

Keh |

red

storm |

|

Mak |

enclosed |

|

K'ank'in |

yellow sun |

|

Muwan |

owl |

|

Pax |

planting time |

|

K'ayab' |

turtle |

|

Kumk'u |

granary |

|

Wayeb' |

five

unlucky days |

|

† Jones

1984 |

|

Haab'

The Haab' was the Maya solar calendar made up of eighteen months of

twenty days each plus a period of five days ("nameless days") at the

end of the year known as Wayeb' (or Uayeb in 16th C. orthography).

Bricker (1982) estimates that the Haab' was first used around 550 BC

with the starting point of the winter solstice.

The Haab' month names are known today by their corresponding names

in colonial-era Yukatek Maya, as transcribed by 16th century sources

(in particular, Diego de Landa and books such as the Chilam Balam of

Chumayel).

Phonemic analyses of Haab' glyph names in pre-Columbian

Maya inscriptions have demonstrated that the names for these

twenty-day periods varied considerably from region to region and

from period to period, reflecting differences in the base language(s)

and usage in the Classic and Postclassic eras predating their

recording by Spanish sources.[11]

Each day in the Haab' calendar was identified by a day number in the

month followed by the name of the month. Day numbers began with a

glyph translated as the "seating of" a named month, which is usually

regarded as day 0 of that month, although a minority treat it as day

20 of the month preceding the named month.

In the latter case, the

seating of Pop is day 5 of Wayeb'. For the majority, the first day

of the year was 0 Pop (the seating of Pop). This was followed by 1

Pop, 2 Pop as far as 19 Pop then 0 Wo, 1 Wo and so on.

As a calendar for keeping track of the seasons, the Haab' was a bit

inaccurate, since it treated the year as having exactly 365 days,

and ignored the extra quarter day (approximately) in the actual

tropical year.

This meant that the seasons moved with respect to the

calendar year by a quarter day each year, so that the calendar

months named after particular seasons no longer corresponded to

these seasons after a few centuries.

The Haab' is equivalent to the

wandering 365-day year of the ancient Egyptians.

Wayeb'

The five nameless days at the end of the calendar, called Wayeb',

were thought to be a dangerous time.

Foster (2002) writes,

"During Wayeb, portals between the mortal realm and the Underworld

dissolved. No boundaries prevented the ill-intending deities from

causing disasters."

To ward off these evil spirits, the Maya had

customs and rituals they practiced during Wayeb'. For example,

people avoided leaving their houses or washing or combing their

hair.

Calendar Round

Neither the Tzolk'in nor the Haab' system numbered the years.

The

combination of a Tzolk'in date and a Haab' date was enough to

identify a date to most people's satisfaction, as such a combination

did not occur again for another 52 years, above general life

expectancy.

Because the two calendars were based on 260 days and 365 days

respectively, the whole cycle would repeat itself every 52 Haab'

years exactly. This period was known as a Calendar Round.

The end of

the Calendar Round was a period of unrest and bad luck among the

Maya, as they waited in expectation to see if the gods would grant

them another cycle of 52 years.

Long Count

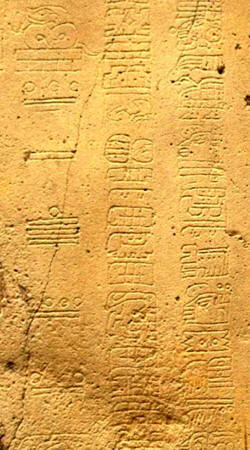

Detail showing three columns of glyphs from 2nd century CE La

Mojarra Stela 1 (below image). The left column gives a Long Count date of

8.5.16.9.7, or 156 CE. The two right columns are glyphs from the Epi-Olmec script.

Since Calendar Round dates can only distinguish in 18,980 days,

equivalent to around 52 solar years, the cycle repeats roughly once

each lifetime, and thus, a more refined method of dating was needed

if history was to be recorded accurately.

To measure dates,

therefore, over periods longer than 52 years, Mesoamericans devised

the Long Count calendar.

Detail showing three columns of glyphs from 2nd century CE La

Mojarra Stela 1.

The left column gives a Long Count date of 8.5.16.9.7, or 156 CE.

The two right columns are glyphs from the Epi-Olmec script.

The Maya name for a day was k'in. Twenty of these k'ins are known as

a winal or uinal. Eighteen winals make one tun. Twenty tuns are

known as a k'atun. Twenty k'atuns make a b'ak'tun.

The Long Count calendar identifies a date by counting the number of

days from the Mayan creation date 4 Ahaw, 8 Kumk'u (August 11, 3114

BC in the proleptic Gregorian calendar or September 6 in the Julian

calendar).

But instead of using a base-10 (decimal) scheme like

Western numbering, the Long Count days were tallied in a modified

base-20 scheme. Thus 0.0.0.1.5 is equal to 25, and 0.0.0.2.0 is

equal to 40. As the winal unit resets after only counting to 18, the

Long Count consistently uses base-20 only if the tun is considered

the primary unit of measurement, not the k'in; with the k'in and

winal units being the number of days in the tun.

The Long Count

0.0.1.0.0 represents 360 days, rather than the 400 in a purely

base-20 (vigesimal) count.

Table of Long Count units

|

Days |

Long Count period |

Long Count period |

Approx solar years |

|

1 |

= 1 K'in |

|

|

|

20 |

= 20 K'in |

= 1 Winal |

0.055 |

|

360 |

= 18 Winal |

= 1 Tun |

1 |

|

7,200 |

= 20 Tun |

= 1 K'atun |

19.7 |

|

144,000 |

= 20 K'atun |

= 1 B'ak'tun |

394.3 |

|

There are also four rarely used higher-order cycles: piktun,

kalabtun, k'inchiltun, and alautun.

Since the Long Count dates are unambiguous, the Long Count was

particularly well suited to use on monuments. The monumental

inscriptions would not only include the 5 digits of the Long Count,

but would also include the two tzolk'in characters followed by the

two haab' characters.

Misinterpretation of the Mesoamerican Long Count calendar is the

basis for a New Age belief that a cataclysm will take place on

December 21, 2012. December 21, 2012 is simply the last day of the

13th b'ak'tun. But that is not the end of the Long Count because the

14th through 20th b'ak'tuns are still to come.

Sandra Noble, executive director of the Mesoamerican research

organization FAMSI, notes that,

"for the ancient Maya, it was a huge

celebration to make it to the end of a whole cycle".

She considers

the portrayal of December 2012 as a doomsday or cosmic-shift event

to be,

"a complete fabrication and a chance for a lot of people to

cash in."[12]

The 2009 science fiction apocalyptic disaster film

2012 is based on this belief.

Supplementary series

Many classic period inscriptions include a supplementary series. The

supplementary series was deciphered by John E. Teeple (1874-1931).

A

supplementary series consists of the following:

Nine lords of the night

Each night was ruled by one of the nine lords of the underworld.

This nine day cycle was usually written as two glyphs: a glyph that

referred to the Nine Lords as a group, followed by a glyph for the

lord that would rule the next night.

Lunar series

A lunar Series generally is written as five glyphs that provide

information about the current lunation, the number of the lunation

in a series of six, the current ruling lunar deity and the length of

the current lunation.

Moon age

The maya counted the number of days in the current lunation. They

started with zero on the first night that they saw the thin crescent

moon.

Lunation number and lunar deity

The Maya counted the lunation in a cycle of six, numbered zero

through 5. Each one was ruled by one of the six Lunar Deities. This

was written as two glyphs: a glyph for the completed lunation in the

lunar count with a coefficient of 0 through 5 and a glyph for one of

the six lunar deities that ruled the current lunation.

Teeple found

that Quirigua Stela E (9.17.0.0.0) is lunar deity 2 and that most

other inscriptions use this same moon number.

It's an interesting

date because it was a Ka'tun completion and a solar eclipse was

visible in the Maya area two days later on the first unlucky day of

Wayeb'.

Lunation length

The length of the lunar month is 29.53059 days so if you count the

number of days in a lunation it will be either 29 or 30 days.

The maya wrote whether the lunar month was 29 or 30 days as two glyphs:

a glyph for lunation length followed by either a glyph made up of a

moon glyph over a bundle with a suffix of 19 for a 29 day lunation

or a moon glyph with a suffix of 10 for a 30 day lunation.

Venus cycle

Another important calendar for the Maya was the Venus cycle.

The

Maya were skilled astronomers, and could calculate the Venus cycle

with extreme accuracy. There are six pages in the Dresden Codex (one

of the Maya codices) devoted to the accurate calculation of the

heliacal rising of Venus.

The Maya were able to achieve such

accuracy by careful observation over many years. There are various

theories as to why Venus cycle was especially important for the

Maya, including the belief that it was associated with war and used

it to divine good times (called electional astrology) for

coronations and war.

Maya rulers planned for wars to begin when

Venus rose.

Notes

1. See entry on Itzamna, in Miller and Taube (1993), pp.99-100.

2. a b Academia de las Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala (1988). Lenguas

Mayas de Guatemala: Documento de referencia para la pronunciación de

los nuevos alfabetos oficiales. Guatemala City: Instituto

Indigenista Nacional. Refer citation in Kettunen and Hemke

(2005:5) for details and notes on adoption among the Mayanist

community.

3. "Mythological" in the sense that when the Long Count was first

devised sometime in the Mid- to Late Preclassic, long after this

date; see for e.g. Miller and Taube (1993, p.50).

4. Finley (2002), Voss (2006, p.138)

5. Malmström (1997): "Chapter 6: The Long Count: The Astronomical

Precision".

6. Coe (1992), Miller and Taube (1993).

7. Miller and Taube (1993, pp.68-71).

8. Classic-era reconstructions are as per Kettunen and Helmke

(2005), pp.45–46..

9. Malmström (1997), and

http://www.dartmouth.edu/~izapa/izapasite.html

10. Kettunen and Helmke (2005), pp.47–48

11. Boot (2002), pp.111–114.

12. As quoted in USA Today (MacDonald 2007).

References

Aveni, Anthony F. (2001). Skywatchers (originally published as:

Skywatchers of Ancient Mexico [1980], revised and updated ed.).

Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-70504-2. OCLC

45195586.

Boot, Erik (2002) (PDF). A Preliminary Classic

Maya-English/English-Classic Maya Vocabulary of Hieroglyphic

Readings. Mesoweb.

http://www.mesoweb.com/resources/vocabulary/Vocabulary.pdf.

Retrieved 2006-11-10.

Bricker, Victoria R. (February 1982). "The Origin of the Maya Solar

Calendar". Current Anthropology (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago

Press, sponsored by Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological

Research) 23 (1): 101–103. doi:10.1086/202782. ISSN 0011-3204. OCLC

62217742.

Coe, Michael D. (1987). The Maya (4th revised ed.). London and New

York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27455-X. OCLC 15895415.

Coe, Michael D. (1992). Breaking the Maya Code. London: Thames &

Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05061-9. OCLC 26605966.

Finley, Michael (2002). "The Correlation Question". The Real Maya

Prophecies: Astronomy in the Inscriptions and Codices. Maya

Astronomy. http://members.shaw.ca/mjfinley/corr.html. Retrieved

2007-05-11.

Foster, Lynn V. (2002). Handbook to Life in the Ancient Maya World.

with Foreword by Peter Mathews. New York: Facts on File. ISBN

0-8160-4148-2. OCLC 50676955.

Ivanoff, Pierre (1971). Mayan Enigma: The Search for a Lost

Civilization. Elaine P. Halperin (trans.) (translation of

Découvertes chez les Mayas, English ed.). New York: Delacorte Press.

ISBN 0-440-05528-8. OCLC 150172.

Jacobs, James Q. (1999). "Mesoamerican Archaeoastronomy: A Review of

Contemporary Understandings of Prehispanic Astronomic Knowledge".

Mesoamerican Web Ring. jqjacobs.net.

http://www.jqjacobs.net/mesoamerica/meso_astro.html. Retrieved

2007-11-26.

Jones, Christopher (1984). Deciphering Maya Hieroglyphs. Carl P.

Beetz (illus.) (prepared for Weekend Workshop April 7 and 8, 1984,

2nd ed.). Philadelphia: University Museum, University of

Pennsylvania. OCLC 11641566.

Kettunen, Harri; and Christophe Helmke (2005) (PDF). Introduction to

Maya Hieroglyphs: 10th European Maya Conference Workshop Handbook.

Leiden, Netherlands: Wayeb and Leiden University.

http://www.mesoweb.com/resources/handbook/. Retrieved 2006-06-08.

MacDonald, G. Jeffrey (27 March 2007). "Does Maya calendar predict

2012 apocalypse?". USA Today (McLean, VA: Gannett Company). ISSN

0734-7456.

http://www.usatoday.com/tech/science/2007-03-27-maya-2012_n.htm.

Retrieved 2009-05-28.

Malmström, Vincent H. (1997) (online reproduction by author). Cycles

of the Sun, Mysteries of the Moon: The Calendar in Mesoamerican

Civilization. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-75197-4.

OCLC 34354774. http://www.dartmouth.edu/~izapa/CS-MM-Cover.html.

Retrieved 2007-11-26.

Miller, Mary; and Karl Taube (1993). The Gods and Symbols of Ancient

Mexico and the Maya: An Illustrated Dictionary of Mesoamerican

Religion. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05068-6. OCLC

27667317.

Robinson, Andrew (2000). The Story of Writing: Alphabets,

Hieroglyphs and Pictograms. London and New York: Thames & Hudson.

ISBN 0-500-28156-4. OCLC 59432784.

Schele, Linda; and David Freidel (1992). A Forest of Kings: The

Untold Story of the Ancient Maya (originally published New York:

Morrow © 1990, pbk reprint ed.). New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN

0-688-11204-8. OCLC 145324300.

Tedlock, Barbara (1982). Time and the Highland Maya. Albuquerque:

University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-826-30577-6. OCLC 7653289.

Tedlock, Dennis notes, trans., ed (1985). Popol Vuh: The Definitive

Edition of the Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life and the Glories of

Gods and Kings. with commentary based on the ancient knowledge of

the modern Quiché Maya. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN

0-671-45241-X. OCLC 11467786.

Thomas, Cyrus (1897). "Day Symbols of the Maya Year". in J. W.

Powell (ed.) (Project Gutenberg EBook online reproduction).

Sixteenth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the

Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1894–1895. Washington DC:

Bureau of American Ethnology, Smithsonian Institution; U.S.

Government Printing Office. pp. 199–266. OCLC 14963920.

http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/18973/.

Thompson, J. Eric S. (1971). Maya Hieroglyphic Writing: An

Introduction. Civilization of the American Indian Series, No. 56

(3rd ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-806-10447-3.

OCLC 275252.

Tozzer, Alfred M. notes, trans., ed (1941). Landa's Relación de las

cosas de Yucatán: a translation. Papers of the Peabody Museum of

American Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University vol. 18.

Charles P. Bowditch and Ralph L. Roys (additional trans.)

(translation of Diego de Landa's Relación de las cosas de Yucatán

[orig. ca. 1566], with notes, commentary, and appendices

incorporating translated excerpts of works by Gaspar Antonio Chi,

Tomás López Medel, Francisco Cervantes de Salazar, and Antonio de

Herrera y Tordesillas. English ed.). Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum

of Archaeology and Ethnology. OCLC 625693.

Voss, Alexander (2006). "Astronomy and Mathematics". in Nikolai

Grube (ed.). Maya: Divine Kings of the Rain Forest. Eva Eggebrecht

and Matthias Seidel (assistant eds.). Cologne, Germany: Könemann.

pp. 130–143. ISBN 978-3-8331-1957-6. OCLC 71165439.

|