|

|

|

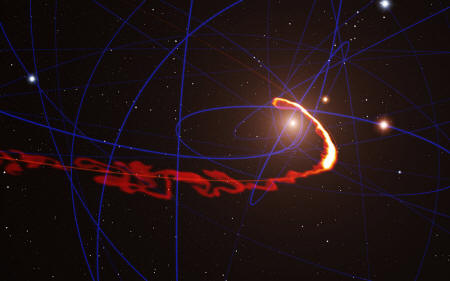

Artist's impression of PSR J1745-2900, a pulsar with a very high magnetic field ("magnetar") potentially just less than half a light year from the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy. The pulsar helped reveal the magnetic field around the Milky Way's supermassive black hole. Image released Aug. 14, 2

A strange, pulsing star has revealed a powerful magnetic field around the giant black hole at the heart of Earth’s Milky Way galaxy, scientists say.

The finding may help shed light on how the galaxy's supermassive black hole devours matter around it and spits out powerful jets of superhot matter, the researchers added.

The center of virtually every large galaxy is suspected to host a supermassive black hole with a mass that can range from millions to billions of times the mass of the sun.

Astronomers think the Milky Way's core is home to the monster black hole called Sagittarius A* - pronounced "Sagittarius A-star" - that is about 4 million times the mass of Earth's sun.

Scientists want to learn more about how black holes distort the universe around them, hoping to see if the leading theory regarding black holes, Einstein's theory of general relativity, holds up or if new concepts might be necessary. One way to see how black holes warp space and time is by looking at clocks near them.

Cosmic versions of clocks are known as pulsars - rapidly spinning neutron stars that regularly give off pulses of radio waves.

Pulsar tells the tale

Astronomers have been searching for pulsars near Sagittarius A* for the past 20 years.

Earlier this year, NASA's NuSTAR telescope helped confirm the existence of such a pulsar apparently less than half a light-year away from the black hole, one that pulsates radio signals every 3.76 seconds.

Scientists quickly analyzed the pulsar using the Effelsberg Radio Observatory of the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn, Germany.

Additional observations were performed in parallel and subsequently with other radio telescopes around the world.

The newfound pulsar, named PSR J1745-2900, belongs to a rare kind of pulsars known as magnetars, which only make up about 1 out of every 500 pulsars found to date.

Magnetars possess extremely powerful magnetic fields, ones about 1,000 times stronger than the magnetic fields of ordinary neutron stars, or 100 trillion times the Earth's magnetic field.

The radio pulses from magnetars are highly polarized, meaning these signals oscillate along one plane in space.

This fact helped the researchers detect a magnetic field surrounding Sagittarius A*.

This image shows the Effelsberg radio telescope during regular observations of the Galactic Center region for unidentified pulsars. The Galactic Center is in the Sagittarius constellation and is only visible for approximately 2 hours and 25 minutes every day.

Image released Aug.

14, 2013.

Black hole magnetic field revealed

Black holes swallow their surroundings, mainly hot ionized gas, in a process of accretion.

Magnetic fields threading within this accretion flow can influence how this infalling gas is structured and behaves.

As radio signals traverse the magnetized gas around black holes, the way they are polarized gets twisted depending on the strength of the magnetic fields.

By analyzing radio waves from the magnetar, the researchers discovered a relatively strong, large-scale magnetic field pervades the area surrounding Sagittarius A*.

In the area around the pulsar, the magnetic field is about 100 times weaker than Earth's magnetic field.

However,

If the magnetic field generated by the infalling gas is accreted down to the event horizon of the black hole - its point of no return - that could help explain the radio and X-ray glow long associated with Sagittarius A*, researchers added.

Astronomers predict there should be thousands of pulsars around the center of the Milky Way.

Despite that, PSR J1745-2900 is the first pulsar discovered there.

The researchers cannot test the leading theory regarding black holes using PSR J1745-2900 - they cannot measure the way it warps space-time accurately enough, since the pulsar is slightly too far away from Sagittarius A* and, being relatively young, its spin is too variable.

The researchers suggest pulsars that are closer to the black hole and are older with less variable spins could help test the theory.

The scientists detailed their findings online Aug. 14 in the journal Nature (A Strong Magnetic Field Around the Supermassive Black Hole at The Centre of The Galaxy).

Giant Black Hole News Editor July 17, 2013 from SPACE Website

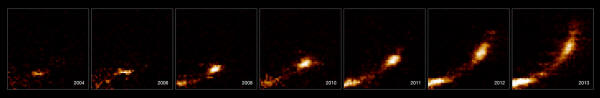

This simulation of a gas cloud passing close to the supermassive black hole

at the centre of the

galaxy shows the situation in mid-2013. Astronomers have spied a huge gas cloud being pulled like taffy around the supermassive black hole at the heart of the Milky Way.

Their observations suggest that the space cloud will be completely ripped apart over the next year as it swirls closer to the galactic drain. Most galaxies are thought to have enormous black holes at their center, and the one at the middle of the Milky Way - roughly 25,000 light years from Earth - has a mass about four million times that of the sun.

Scientists first spotted a gas cloud accelerating toward our galaxy's supermassive black hole in 2011:

Data from 2004 show that the cloud was once shaped like a circular blob, but the intense gravitational forces of the black hole have now stretched it spaghetti-thin, researchers say.

Their new observations were made this past April with the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile.

The cloud's light becomes more difficult to spot the more it gets stretched, but a 20-hour exposure with the VLT's special infrared spectrometer, called SINFONI, allowed scientists to measure the cosmic body getting closer to its doom.

Scientists still don't know where exactly the gas cloud came from, but they say the new observations rule out some possibilities.

At its closest approach, the grossly stretched cloud is a little more than 15 billion miles (25 billion km) from the black hole itself - about five times Neptune's distance from the sun, the researchers say.

This is dangerously close considering the black hole's humongous mass, and the cloud, Stefan Gillessen says, is "barely escaping falling right in."

These observations from ESO's Very Large Telescope, using the SINFONI instrument, show how a gas cloud is being stretched and ripped apart

as it passes close to

the supermassive black hole at the centre of the galaxy.

Gillessen and colleagues say the head of the cloud has already whipped around the black hole and is speeding back in our direction at more than 6.2 million mph (10 million km/h), roughly one percent the speed of light.

The tail is following at a slower pace (about 1.6 million mph, or 2.6 million km/h).

The new observations will be detailed in the Astrophysical Journal. Scientists plan to intensely monitor the region throughout the year to watch as the cloud gets completely torn apart - a rare opportunity to test theories about how black holes pull in mass.

|