|

by Davide Castelvecchi

14 September 2016

from

Nature Website

Voyage to

Praesepe

A virtual journey from the Solar System to the

Praesepe Cluster

(M44), some 577 light years

away, based on Gaia's 3D mapping of individual stars.

Gaia also measured

the velocities of some of the stars, represented here by arrows.

First results from Gaia

probe

also seem to solve old

controversy

over Pleiades cluster.

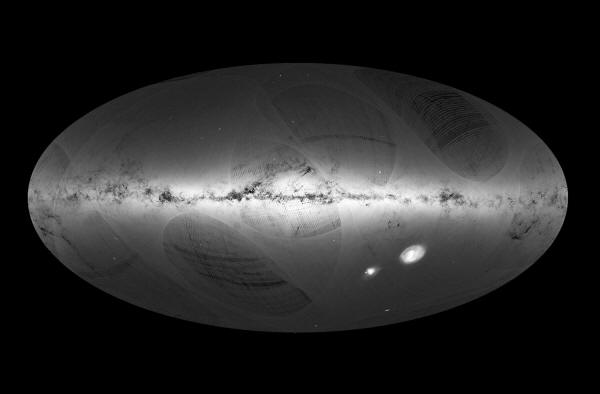

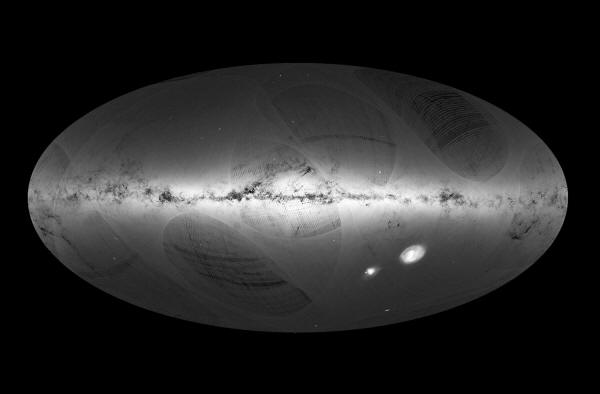

The European Space Agency (ESA) has released the largest, most

detailed map yet of the Milky Way.

It pinpoints the 3D positions of

1.1 billion stars, almost 400 million of which were previously

unknown to science.

ESA's

Gaia space observatory mapped out

the catalogue. The results are expected to transform what

astronomers

know about the Galaxy

- allowing

researchers to discover new extrasolar planets, examine the

distribution of dark matter and fine-tune models of how stars

evolve.

Hundreds of astronomers began to access

the

database as soon

as it was made publicly available on 14 September, says Gaia project

scientist Timo Prusti, who works at ESA's European Space Research

and Technology Centre in Noordwijk, the Netherlands.

"My advice to

the astronomical community is: please enjoy with us," he said at a

press conference in Madrid.

Within 24 hours, more than 11,000 users

had accessed the catalogue, ESA said, and independent teams have

begun to post papers based on Gaia data on the preprint repository

arXiv.

Gaia has already found more stars than

researchers expected, which suggests that the Milky Way is slightly

bigger than previously estimated, says Gisella Clementini, a Gaia

researcher at the Bologna Astronomical Observatory in Italy.

But few new results were announced at

the catalogue's unveiling, because Gaia's team was allowed to do

only limited analyses before the data release - unusual for space

observatories, whose mission scientists often have up to a year's

exclusive use of their data before sharing them with the world.

One notable result, however, is a

measurement of the distance of

the Pleiades,1

a cluster of stars in the constellation Taurus that has been the

subject of

a long-running controversy.

Whereas numerous measurements put

the Pleiades cluster at a distance of about 135 parsecs (440 light

years) from the Sun, Gaia's predecessor, ESA's

Hipparcos mission,

found it to be about 15 parsecs closer.

Gaia measured 134 parsecs, give or take

6 parsecs - suggesting that the Hipparcos findings were inaccurate.

Anthony Brown, an astronomer at the Leiden Observatory in the

Netherlands who chairs Gaia's data-processing collaboration,

stresses that the results are preliminary and that they could change

once Gaia collects more data.

(Ultimately, Gaia should be the first

mission able to measure the distances of individual stars in the

cluster, rather than an average.)

But there's scant possibility that Gaia's results will be corrected so much that they agree with the

Hipparcos results, thinks David Soderblom, an astronomer at the

Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland.

"It's not

impossible but it sure isn't very likely at this point," he says.

"That, to me, is basically the answer."

Soderblom expects that the

trouble with the Hipparcos measurement may have been in corrections

made to account for the unusual brightness of stars in the cluster.

The Milky Way and its neighbouring

galaxies

are shown in this map based on Gaia satellite data:

brighter regions indicate denser concentrations of stars.

Gaia launched in late 2013 and

started its scientific mission in July 2014.

The spacecraft cost

€450 million (US$500 million), but the mission's total cost,

including the expense of operations and running data centres, is

close to €1 billion. The preliminary catalogue released today is

based on Gaia's first 14 months of data-taking.

Gaia does not take

still exposures as ordinary telescope cameras do:

instead, it

constantly spins on its axis, making a full revolution every six

hours and tracking the streaks that stars leave along its

1-gigapixel detector.

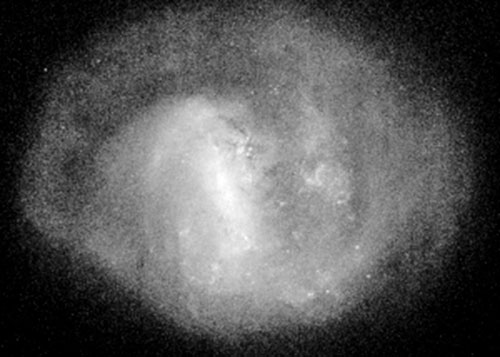

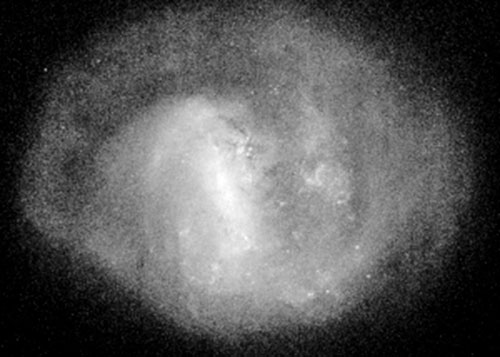

ESA/Gaia/DPAC

A reconstruction of the Large Magellanic

Cloud

based on Gaia data.

By comparing scans of the sky taken

six months apart, researchers are able to triangulate and

measure stars' distances using the parallax effect, a technique

that dates back to ancient Greece.

In the first release of Gaia's catalogue, more than two million stars have been

labeled

both with measurements of their distances from the Sun and their

motion, obtained by comparing Gaia data with those from

Hipparcos.

In future releases, the catalogue will grow to

include the distances and velocities of more than one billion

stars.

With more years of observation,

Gaia's measurements will become so accurate that the distances

of many of the Galaxy's stars will be pinpointed to within 1%.

"What Gaia is going to do is going

to be phenomenal," says Wendy Freedman, an astronomer at the

University of Chicago in Illinois. "It will be the fundamental

go-to place for astronomers for decades to come."

References

1.

Brown, A. G. A. et al.

Astron. Astrophys -

Gaia Data Release 1 - Summary of the

Astrometric, Photometric, and Survey Properties - (2016).

One notable result, however, is a

measurement of the distance of the Pleiades,

a cluster of stars in the constellation Taurus that has been the

subject of a long-running subject. See "Controversy

Reignites over Distance of Pleiades Star Cluster".

|