|

by Denise Chow

SPACE Staff Writer

July 08, 2010

from

Space Website

Giant propeller-shaped structures have

been discovered in the rings of Saturn and appear to be created by a

new class of hidden moons, NASA announced Thursday.

NASA's Cassini spacecraft spotted the distinctive structures inside

some of

Saturn's rings, marking the first time scientists have

managed to track the orbits of individual objects from within a

debris disk like the one that makes up Saturn's complicated ring

system.

"Observing the motions of these disk-embedded objects provides a

rare opportunity to gauge how the planets grew from, and interacted

with, the disk of material surrounding the early sun," said the

study's co-author Carolyn Porco, one of the lead researchers on the

Cassini imaging team based at the Space Science Institute in

Boulder, Colo.

"It allows us a glimpse into how the solar system

ended up looking the way it does."

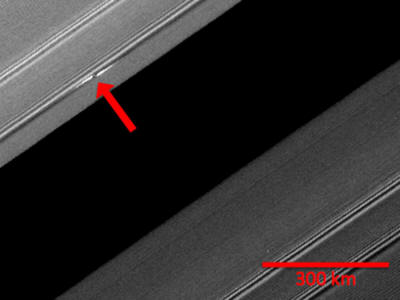

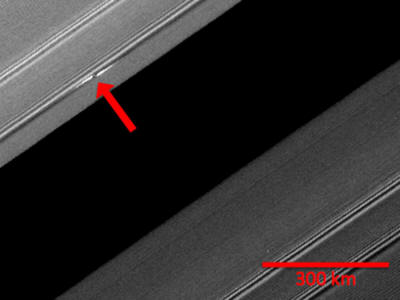

Photos of the propellers taken by Cassini show them to be

huge

structures several thousands of miles long.

A

propeller-shaped structure created by an unseen moon

is brightly

illuminated on the sunlit side of Saturn's rings

in this image

obtained by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft.

The image was

released on July 8, 2010.

Credit: NASA/JPL/SSI

By understanding how

they form, astronomers hope to glean insight into the debris disks

around other stars as well, researchers said.

The results of the study are detailed in the July 8 issue of the

journal Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Propellers at Saturn

Cassini scientists have seen double-armed propeller structures in

Saturn's rings before, but on a smaller scale than the larger,

newfound features.

They were first spotted in 2006 in an area now

known as the "propeller belt," which is located in the middle of

Saturn's outermost dense ring - the A ring.

The propellers are actually gaps in the ring material were created

by a new class of objects, called moonlets, that are smaller than

known moons but larger than the particles making up Saturn's rings.

It is estimated that these moonlets could number in the millions,

according to Cassini scientists.

The moonlets clear the space immediately around them to generate the

propeller-like features, but are not large enough to sweep clear

their entire orbit around Saturn, as seen with the moons Pan

and Daphnis (photos of Saturn rings and moons below.)

But in the new study, researchers a new legion of larger and rarer

moons in a separate part of the A ring, farther out from Saturn.

These much larger moons create propellers that are hundreds of times

larger than those previously described, and these objects have been

tracked for about four years.

The study was led by Cassini imaging team associate Matthew Tiscareno at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y.

The propeller features for these larger moons are up to thousands of

miles long and several miles wide. The moons embedded in Saturn's

rings appear to kick up ring material as high as 1,600 feet (0.5 km)

above and below the ring plane.

This is much greater than the typical ring thickness of about 30

feet (10 meters), researchers said.

Hidden Saturn moons

Still, the

Cassini spacecraft is too far away to see the moons amid

the swirling ring material that surrounds them. Yet, scientists

estimate that the moons measure approximately half a mile (about one

km) in diameter, based on the size of the propellers.

According to their research, Tiscareno and his colleagues estimate

that there are dozens of these giant propellers. In fact, 11 of them

were imaged multiple times between 2005 and 2009.

One such propeller, nicknamed Bleriot after the famous aviator

Louis

Bleriot, has shown up in more than 100 separate Cassini images and

one ultraviolet imaging spectrograph observation during this time.

"Scientists have never tracked disk-embedded objects anywhere in the

universe before now," said Tiscareno.

"All the moons and planets we

knew about before orbit in empty space. In the propeller belts, we

saw a swarm in one image and then had no idea later on if we were

seeing the same individual objects. With this new discovery, we can

now track disk-embedded moons individually over many years."

Over their four years of observation, the researchers noticed shifts

in the orbits of the giant propellers as they travel around Saturn,

but the cause of these disturbances have not yet been determined.

The shifting orbits could be caused by collisions with other smaller

ring particles, or could be responses to these particles' gravity,

the researchers said. The orbital paths of these moonlets could also

be altered due to the gravitational attraction of large moons

outside of Saturn's rings.

Scientists will continue to monitor the moons to see if the disk

itself is driving the chances, similar to the interactions that

occur in young solar systems.

If so, Tiscareno said, this would be

the first time such a measurement has been made directly.

"Propellers give us unexpected insight into the larger objects in

the rings," said Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist based at

NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif.

"Over the next

seven years, Cassini will have the opportunity to watch the

evolution of these objects and to figure out why their orbits are

changing."

NASA launched the

Cassini probe in 1997 and it arrived at Saturn in

2004, where it dropped the European

Huygens probe on the cloudy

surface of

Titan, Saturn's largest moon.

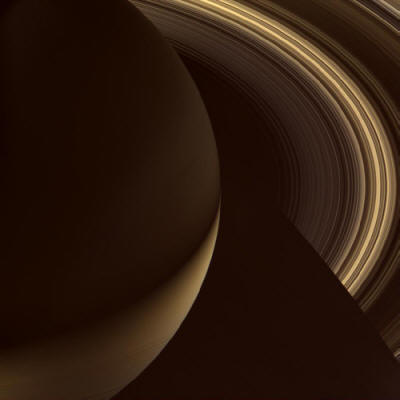

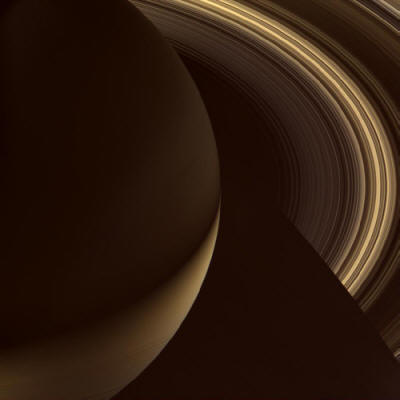

Saturn gets a new

look in this new image

taken by the Cassini

spacecraft studying the ringed planet.

The vivid orange and

yellow hues of Saturn's atmosphere,

and the blue tinge of

its rings at far right,

highlight this

composite of several images taken by Cassini's wide-angle camera.

To build this view,

researchers used special camera filters

that are sensitive

only to certain types of infrared light.

Cassini's camera

recorded this image on Dec. 13, 2006

from a distance of

about 511,000 miles (822,000 kilometers) from Saturn.

Cassini was slated to be

decommissioned in September of this year (2010), but received a life

extension that now runs through 2017.

|