|

por Andrés Eloy Martínez

04 Agosto 2010

del Sitio Web

ElUniversal

|

Por primera vez, los investigadores pudieron analizar la longitud de

onda de radiación infrarroja del planeta |

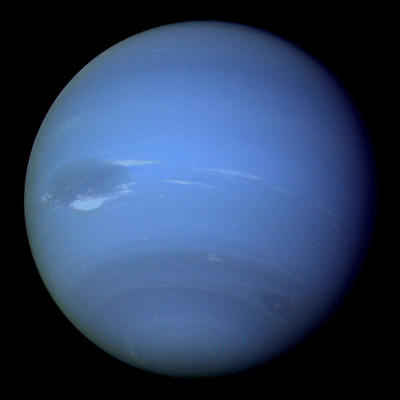

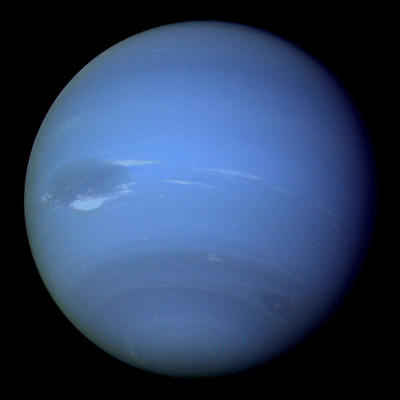

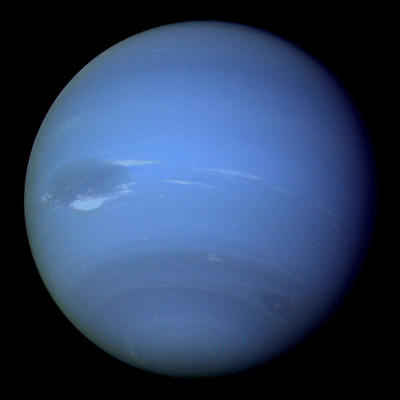

El planeta Neptuno habría recibido el impacto de una cometa hace 200

años

(Foto: Especial Max Planck Institute)

Científicos del

Instituto Max Planck descubrieron evidencias del

impacto de un cometa sobre el planeta Neptuno hace 200 años, de

acuerdo a una comunicado del propio instituto.

Cuando el

cometa Shoemaker-Levy 9 golpeó, hace 16 años, a Júpiter,

científicos de todo el mundo se prepararon para el gran espectáculo:

instrumentos a bordo de las naves espaciales Voyager 2, Galileo y

Ulises capturaron datos de este raro evento.

Hoy, estos mismos datos ayudan a los científicos a detectar impactos

de cometas ocurridos hace muchos años.

Estas grandes "bolas de nieve y polvo", como las llaman los

astrónomos, dejan huellas en la atmósfera de los planetas gigantes

de gas:

-

agua

-

dióxido de carbono

-

monóxido de carbono

-

ácido

cianhídrico

-

sulfuro de carbono

Estas moléculas pueden ser detectadas en la luz que el planeta

refleja hacia el espacio.

En febrero de 2010, científicos de este mismo instituto descubrieron

fuerte evidencia del impacto de un cometa en Saturno alrededor hace

230 años.

Ahora, nuevas mediciones realizadas por el

observatorio espacial Herschel indican que Neptuno experimentó un hecho similar.

Por primera vez, los investigadores pudieron analizar la longitud de

onda de radiación infrarroja de Neptuno.

La atmósfera del planeta más exterior de nuestro sistema solar se

compone principalmente de hidrógeno y helio, con trazas de agua,

dióxido de carbono y monóxido de carbono.

Los científicos detectaron una inusual distribución del monóxido de

carbono en la capa superior de la atmósfera, denominada estratosfera,

se encontraron con una mayor concentración que en la capa inferior o

troposfera.

"Esta alta concentración de monóxido de carbono en la estratosfera

sólo puede explicarse por un origen externo", señaló el científico

Paul Hartogh, investigador principal de la misión Herschel.

"Normalmente, las concentraciones de monóxido de carbono en la

troposfera y la estratosfera deben ser iguales o disminuir con el

aumento de la altura", añadió.

La única explicación para estos resultados es el

impacto de un

cometa.

Tal colisión desmorona el cometa, mientras que el monóxido de

carbono atrapado en el cometa de hielo se libera y con los años se

distribuye por toda la estratosfera.

El instrumento con el que se logro este descubrimiento, llamado red

de foto-detector, cámara y espectrómetro, fue desarrollado en el

Instituto Max Planck.

Con éste se analiza la longitud de onda de radiación infrarroja,

también conocida como radiación calórica, que los cuerpos como

Neptuno emiten en el frió del espacio.

El satélite Herschel lleva a bordo el telescopio más grande que

jamás haya sido operado en el espacio.

Cometary Impact

...on Neptune

July 16, 2010

from

MPS Website

Measurements performed by the

space observatory Herschel point to a

collision about two centuries ago.

A comet may have hit the planet Neptune about two centuries ago.

This is indicated by the distribution of carbon monoxide in the

atmosphere of the gas giant that researchers - among them scientists

from the French observatory LESIA in Paris, from the Max Planck

Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Katlenburg-Lindau (Germany)

and from the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics

(MPE) in Garching (Germany) - have now studied.

The scientists analyzed data

taken by the research satellite Herschel, that has been orbiting

the Sun in a distance of approximately 1.5 million kilometers since

May 2009. (Astronomy & Astrophysics, published online on July 16th,

2010)

When the

comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 hit Jupiter sixteen years ago,

scientists all over the world were prepared: instruments on board

the space probes Voyager 2, Galileo and Ulysses documented every

detail of this rare incident.

Today, this data helps scientists

detect cometary impacts that happened many, many years ago.

The "dusty

snowballs" leave traces in the atmosphere of the gas giants: water,

carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, hydrocyanic acid, and carbon

sulfide. These molecules can be detected in the radiation the planet

radiates into space.

In February 2010 scientists from MPS discovered strong evidence for

a cometary impact on Saturn about 230 years ago (see Astronomy and

Astrophysics, Volume 510, February 2010). Now new measurements

performed by the instrument

PACS (Photodetector Array Camera and

Spectrometer) on board the Herschel space observatory indicate that

Neptune experienced a similar event.

For the first time, PACS allows

researchers to analyze the long-wave infrared radiation of Neptune.

Figure 1

Two centuries ago a comet may have hit Neptune, the outer-most

planet in our solar system.

(Credits: NASA)

The atmosphere of the outer-most planet of our solar system mainly

consists of hydrogen and helium with traces of water, carbon dioxide

and carbon monoxide.

Now, the scientists detected an unusual

distribution of carbon monoxide: In the upper layer of the

atmosphere, the so-called stratosphere, they found a higher

concentration than in the layer beneath, the troposphere.

"The

higher concentration of carbon monoxide in the stratosphere can only

be explained by an external origin", says MPS-scientist Paul Hartogh,

principle investigator of the Herschel science program 'Water and

related chemistry in the solar system'.

"Normally, the

concentrations of carbon monoxide in troposphere and stratosphere

should be the same or decrease with increasing height", he adds.

The only explanation for these results is a cometary impact.

Such a

collision forces the comet to fall apart while the carbon monoxide

trapped in the comet’s ice is released and over the years

distributed throughout the stratosphere.

"From the distribution of

carbon monoxide we can therefore derive the approximate time, when

the impact took place", explains Thibault Cavalié from MPS.

The

earlier assumption that a comet hit Neptune two hundred years ago

could thus be confirmed. A different theory according to which a

constant flux of tiny dust particles from space introduces carbon

monoxide into Neptune’s atmosphere, however, does not agree with the

measurements.

In Neptune’s stratosphere the scientists also found a higher

concentration of methane than expected. On Neptune, methane plays

the same role as water vapor on Earth: the temperature of the so-called

tropopause - a barrier of colder air separating troposphere and

stratosphere - determines, how much water vapor can rise into the

stratosphere. If this barrier is a little bit warmer, more gas can

pass through.

But while on Earth the temperature of the tropopause

never falls beneath minus 80 degrees Celsius, on Neptune the

tropopause's mean temperature is minus 219 degrees.

Therefore, a gap in the barrier of the tropopause seems to be

responsible for the elevated concentration of methane on Neptune.

With minus 213 degrees Celsius, at Neptune’s southern Pole this air

layer is six degrees warmer than everywhere else allowing gas to

pass more easily from troposphere to stratosphere.

The methane,

which scientists believe originates from the planet itself, can

therefore spread throughout the stratosphere.

The instrument PACS was developed at the Max Planck Institute for

Extraterrestrial Physics. It analyzes the long-wave infrared

radiation, also known as heat radiation, that the cold bodies in

space such as Neptune emit.

In addition, the research satellite

Herschel carries the largest telescope ever to have been operated in

space.

|