|

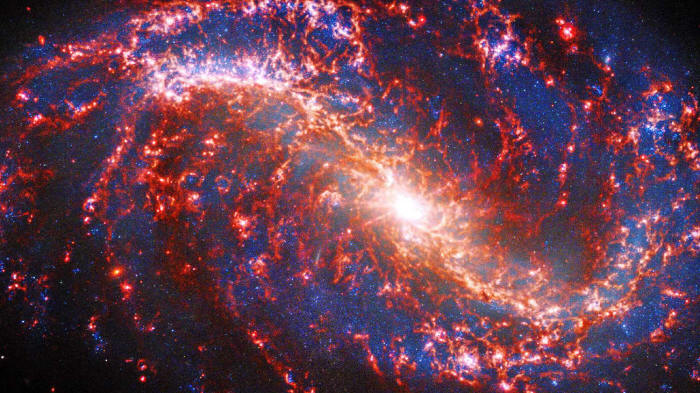

of the galaxy NGC 7496 reveals bright channels

of dust

and gas where stars are actively forming. the mega-telescope started delivering data, astronomers reported exciting new discoveries about galaxies, stars, exoplanets and even Jupiter...

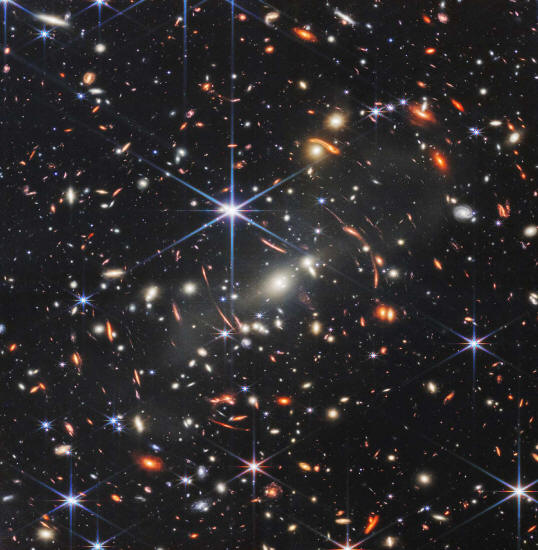

As soon as President Biden unveiled the first image from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) on July 11, Massimo Pascale and his team sprang into action.

Coordinating over Slack, Pascale, an astrophysicist at the University of California, Berkeley, and 14 collaborators divvied up tasks.

The image showed thousands of galaxies in a pinprick-size portion of the sky, some magnified as their light bent around a central cluster of galaxies.

The team set to work scrutinizing the image, hoping to publish the very first JWST science paper.

Three days later, just minutes before the daily deadline on arxiv.org, the server where scientists can upload early versions of papers, the team submitted their research.

They missed out on being first by 13 seconds,

The victors, Guillaume Mahler at Durham University in the United Kingdom and colleagues, analyzed that same first JWST image.

The "healthy competition," as Mahler calls it, highlights the enormous volume of science that is already coming from JWST, days after scientists started receiving data from the long-awaited, infrared-sensing mega-telescope.

The Dawn of Time

One of JWST's much-touted abilities is the power to look back in time to the early universe and see some of the first galaxies and stars.

Already, the telescope - which launched on Christmas Day 2021 and now sits 1.5 million kilometers from Earth - has spotted the most distant, earliest galaxy known.

A newfound galaxy dubbed GLASS-z13, which is so far away that we see it as it appeared 300 million years after the Big Bang, now holds the record for the earliest known galaxy.

That record is not expected to last long.

NASA/CSA/ESA/STScI

Two teams found the galaxy when they separately analyzed JWST observations for the GLASS survey, one of more than 200 science programs scheduled for the telescope's first year in space.

Both teams, one led by Rohan Naidu at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Massachusetts and the other by Marco Castellano at the Astronomical Observatory of Rome, identified two especially remote galaxies in the data:

Both galaxies look extremely small, perhaps 100 times smaller than the Milky Way, yet they show surprising rates of star formation and already contain 1 billion times the mass of our sun - more than expected for galaxies this young.

One of the young galaxies even shows evidence of a disklike structure. More studies will be done to break apart their light to glean their characteristics.

Another early-universe program has also turned up "incredibly distant galaxies," said Rebecca Larson, an astronomer at the University of Texas, Austin and a member of the Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science (CEERS) survey.

Just weeks into the survey, the team has bagged a handful of galaxies from the universe's first 500 million years, although Larson and her colleagues haven't released their exact findings yet.

The telescope's first public image shows a cluster of galaxies called SMACS 0723, which is so heavy it warps and magnifies

the light from distant galaxies beyond it.

More early galaxies hide in the image of the galaxy cluster presented by President Biden and studied by Pascale and Mahler.

Pascale and Mahler found up to 16 remote galaxies that have been magnified in the image; their exact ages aren't yet known.

The telescope took a closer look at one distant galaxy in the image, a smudge of light that dates to 700 million years after the Big Bang.

Now scientists are hoping the telescope will find an absence of heavy elements in even earlier galaxies - evidence that these galaxies contain only Population III stars, the hypothesized first stars in the universe, thought to have been monstrously huge and made entirely from hydrogen and helium.

(Only as those stars exploded did they forge heavier elements such as oxygen and spew them into the cosmos.)

Galactic Structure

For scientists seeking to understand the structure of galaxies and how stars form within them, JWST has already provided impactful data.

JWST sees ribbonlike channels of star formation in galaxy NGC 7496 that were previously shrouded in dust and therefore invisible in images taken

by the Hubble Space Telescope.

One observing program, led by Janice Lee at the National Science Foundation's NOIRLab in Arizona, looks for young sites of star formation in galaxies.

On behalf of Lee's team, JWST observed a galaxy 24 million light-years away called NGC 7496, whose young star-forming regions have until now been shrouded in darkness.

Hubble's instruments were unable to penetrate the thick dust and gas that surrounds these regions.

JWST, though, can see infrared light that bounces off the dust, allowing the telescope to probe close to the moments when the stars switched on and nuclear fusion ignited in their cores.

What's most remarkable, she said, is that NGC 7496 is a normal galaxy,

Yet under the watchful eye of JWST, it suddenly comes to life and reveals channels where stars are forming.

John Barentine, an astronomer at the dark-sky conservation firm Dark Sky Consulting in Arizona, meanwhile, made a more serendipitous discovery in one of JWST's first images.

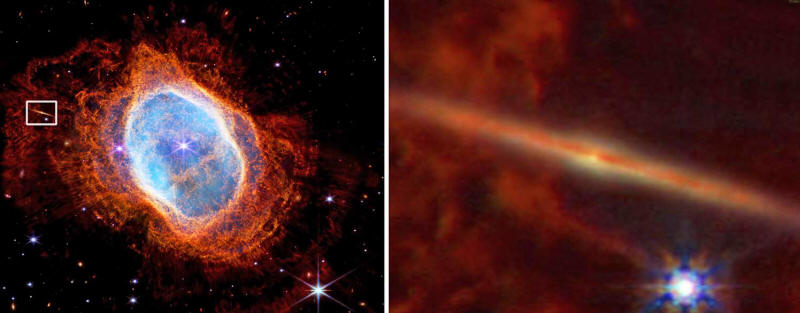

The telescope's picture of the Southern Ring Nebula, 2,500 light-years from Earth, showed remarkable clarity.

Off to the side, an intriguing galaxy viewed edge-on (a unique vantage point for studying the galaxy's central bulge), previously misidentified as part of the nebula itself, poked into view.

A disk galaxy viewed perfectly edge-on was spotted in JWST's image of the Southern Ring Nebula. The unique vantage point lets scientists

study the structure of the galaxy's central bulge.

An Eye on Stars and Planets

Smaller targets are in JWST's crosshairs, too, including the planets of our own solar system.

Jupiter appeared in magnificent fashion as part of the first batch of images, captured in an exposure lasting just 75 seconds. Astronomers know that Jupiter's upper atmosphere is hundreds of degrees hotter than the lower atmosphere, but they aren't sure why.

By detecting infrared light, JWST could see the heated upper atmosphere shining; it appears as a red ring around the planet.

Melin's program plans to use JWST in the coming weeks to study the driving force behind this atmospheric heating.

The mysterious, red-hot glow of Jupiter's upper atmosphere is visible in JWST's 75-second exposure of the planet. Also visible are Jupiter's thin ring and its icy moon Europa shining brightly on the left. A small atmospheric disturbance, visible on the planet's bottom edge,

is caused by an interaction with the volcanic moon Io.

Hiding in JWST's image of Jupiter is the volcanic moon Io interacting with Jupiter's aurora - creating a small bump in the aurora.

The image reveals,

The effect has been seen before, but it was easily picked out by JWST with barely a glance at the planet.

JWST is probing planets in other star systems too. Already, the telescope has taken a peek at the famous TRAPPIST-1 system, a red dwarf star with seven Earth-size worlds (some potentially habitable), though the data is still being analyzed.

Early observations have been released of a less hospitable planet, a "hot Jupiter" called WASP-96 b, in a tight 3.4-day orbit around its star.

JWST found water vapor in the planet's atmosphere, confirming evidence of water reported days earlier by Chima McGruder of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center and colleagues, who used a ground-based telescope.

But JWST can go further; by observing WASP-96 b's ratio of carbon to oxygen, it may be able to solve a confounding mystery about hot Jupiters:

More oxygen would suggest that the gas giant initially formed near the star, while a higher carbon ratio would suggest that it formed in more carbon-rich regions further away.

Meanwhile, JWST may have spotted a temporary light in the sky - a short-lived event known as a transient - which it was not initially designed to do.

The astronomer Mike Engesser and colleagues at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland (the operations center for JWST), noticed a bright object not apparent in Hubble images of the same region.

They think it's a supernova, or exploding star, some 3 billion light-years away - proof that the telescope can find these events.

JWST should be capable of finding far more distant supernovas too, which will give it another way to serve as a probe of the early universe.

It may also find stars being torn apart by the supermassive black holes that reside at galaxies' centers, something no previous telescope has seen.

Transients, like other astronomical phenomena, are set to be redefined.

After decades of planning and construction, JWST has hit the sky running.

The issue now is keeping pace with the constant barrage of science coming down from a machine so complex yet faultless it almost defies belief that it was built by human brains.

NOTES:

|