|

by

Ethan Siegel

Published

March 2023.

Updated September 24, 2025

from

BigThink Website

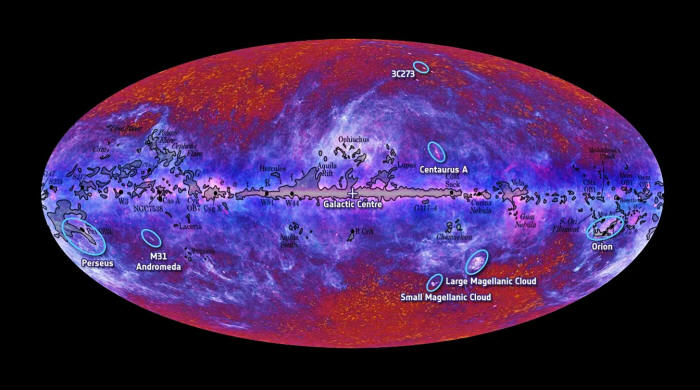

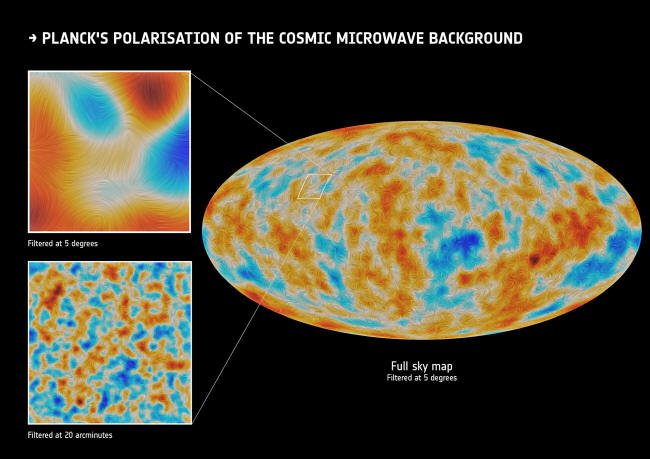

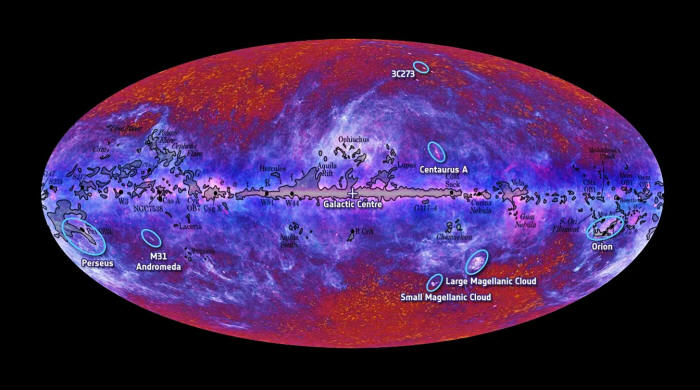

Credit: ESA, HFI and

LFI consortia,

2010; CO map from T.

Dame et al., 2001

|

When

the entire sky is viewed in a variety of wavelengths,

certain sources corresponding to distant objects beyond

our galaxy are revealed.

This

first all-sky map from Planck includes not only the

cosmic microwave background, but also extragalactic

contributions and the foreground contributions from

matter within the Milky Way itself.

All

of these must be understood to tease out the appropriate

temperature and polarization signals. |

The

hot Big Bang

is often

touted as the

beginning

of the Universe.

But

there's one piece of evidence

we can't

ignore

that shows

otherwise...

Key Takeaways

-

For

many decades, people conflated the hot Big Bang,

describing the early Universe, with a singularity: that

this "Big Bang" was the 'birth' of space and time.

-

However, in the early 1980s, a new theory called cosmic

inflation came along, suggesting that before the hot Big

Bang, the Universe behaved very differently, pushing any

hypothetical singularity unobservably far back. Earlier

this century, some very strong evidence arrived showing

that there was a Universe before the Big Bang,

demonstrating that the Big Bang wasn't truly the 'start'

of it all.

-

Earlier this century, some very strong evidence arrived

showing that there was a Universe before the Big Bang,

demonstrating that the Big Bang wasn't truly the start

of it all.

The notion of

the Big Bang goes back nearly 100 years, when

the first evidence for the expanding Universe appeared.

If the Universe is expanding and cooling

today, that implies a past that was smaller, denser, and hotter.

In our imaginations, we can extrapolate back to

arbitrarily small sizes, high densities, and hot temperatures:

all the way to a singularity, where all of

the Universe's matter and energy was condensed in a single

point.

For many decades, these two notions of the Big

Bang - of the hot dense state that describes the early Universe and

the initial singularity - were inseparable.

But beginning in the 1970s, scientists started identifying some

puzzles surrounding the Big Bang, noting several properties of the

Universe that weren't explainable within the context of these two

notions simultaneously.

When

cosmic inflation was first put forth and

developed in the early 1980s, it separated the two definitions of

the Big Bang, proposing that the early hot, dense state never

achieved these singular conditions, but rather that a new,

inflationary state preceded it.

There really was a Universe before the hot Big

Bang, and some very strong evidence from the 21st century truly

proves that it's so.

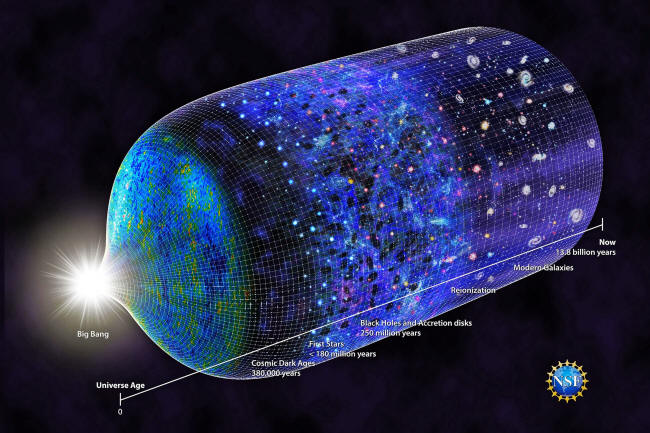

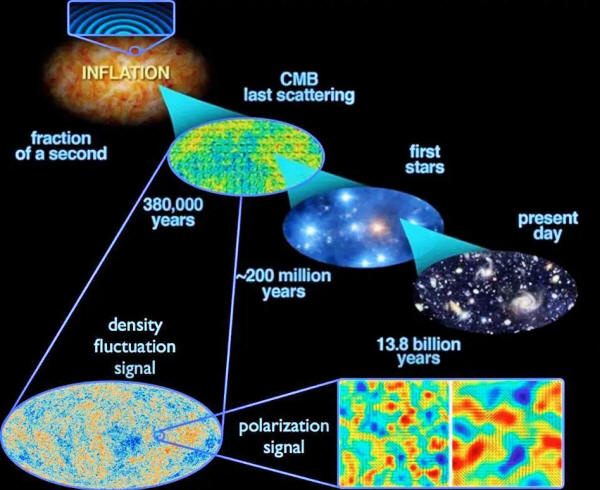

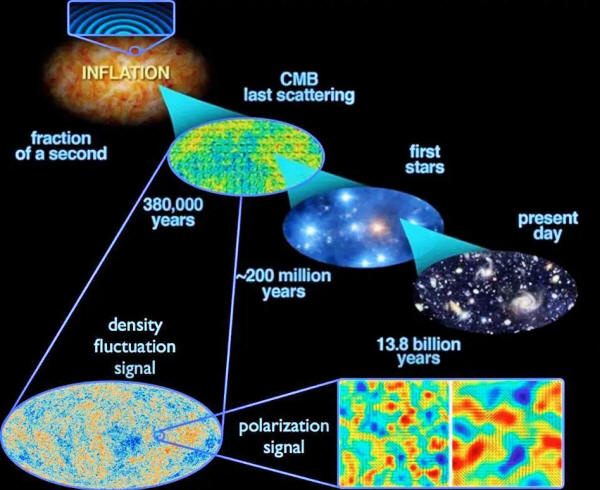

Credit: Nicole Rager Fuller

National

Science Foundation

|

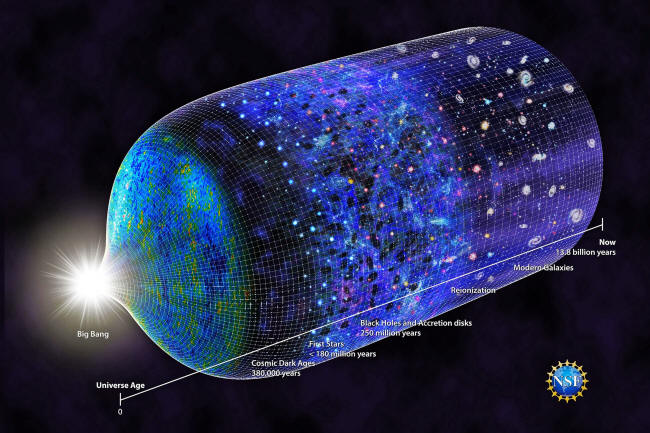

Our

entire cosmic history is theoretically well-understood,

but difficult to depict in a static, 2D image.

The

Universe's present expansion rate and energy composition

are related, which is why most modern illustrations of

our cosmic history have a tube-like shape: where they

often (dubiously) depict an initial singularity, a

period of inflation, and then a slower expansion that

changes with time while our Universe evolves.

No one

diagram encodes all of these details correctly,

including the one shown here, which seems to maintain a

constant "size" for the Universe, disagreeing with

reality. |

Although we're certain that we can describe the very early Universe

as being hot, dense, rapidly expanding, and full of

matter-and-radiation - i.e., by the hot Big Bang - the question of

whether that was truly the beginning of the Universe or not is one

that can be answered with evidence.

The differences between a Universe that began

with a hot Big Bang and a Universe that had an inflationary phase

that precedes and sets up the hot Big Bang are subtle, but

tremendously important.

After all, if we want to know what the very

beginning of the Universe was, we need to look for evidence from the

Universe itself.

In a hot Big Bang that we extrapolate all the way back to

a

singularity, the Universe achieves arbitrarily hot temperatures and

high energies.

Although the Universe will have an "average"

density and temperature, there will be imperfections throughout it:

overdense regions and underdense regions

alike.

As the Universe expands and cools, it also

gravitates, meaning that overdense regions will attract more

matter-and-energy into them, growing over time, while underdense

regions will preferentially give up their matter-and-energy into the

denser surrounding regions, creating the seeds for an eventual

cosmic web of structure.

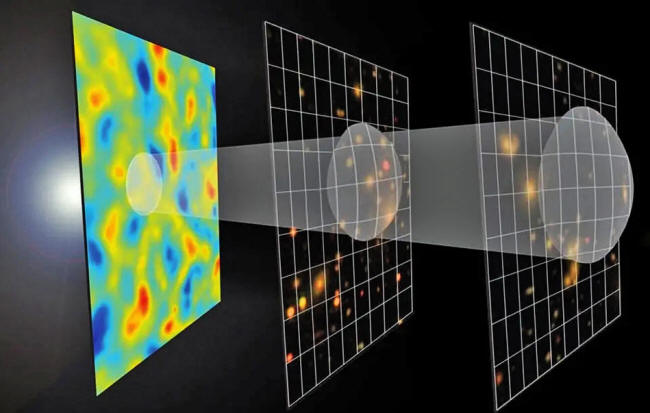

Credit: E.M. Huff, SDSS-III

South Pole

Telescope, Zosia Rostomian

|

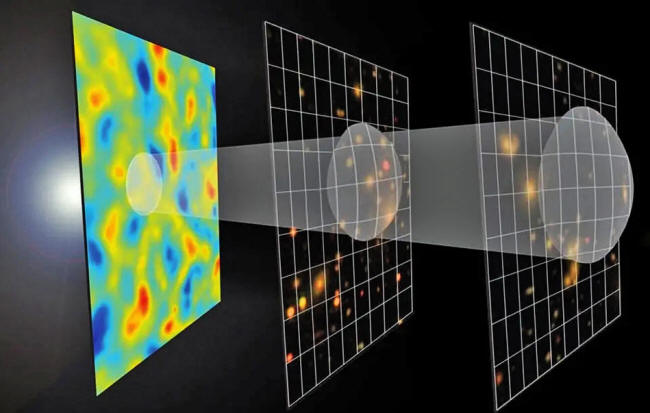

The

density fluctuations in the 'cosmic microwave background'

(CMB) provide the seeds for modern cosmic structure to

form, including stars, galaxies, clusters of galaxies,

filaments, and large-scale cosmic voids.

But the CMB

itself cannot be seen until the Universe forms neutral

atoms out of its ions and electrons, which takes

hundreds of thousands of years, and the stars won't form

for even longer: 50-to-100 million years. |

But the details that will emerge in the cosmic web are determined

far earlier, as the "seeds" of the large-scale structure were

imprinted in the very early Universe.

Today's stars, galaxies, clusters of galaxies,

and filamentary structures on the largest scales of all can be

traced back to density imperfections from when neutral atoms first

formed in the Universe, as those "seeds" would grow, over hundreds

of millions and even billions of years, into the rich cosmic

structure we see today.

Those seeds exist all throughout the Universe,

and remain, even today, as temperature imperfections in the Big

Bang's leftover glow:

the

cosmic microwave background.

As measured by the

WMAP satellite in the 2000s

and its successor, the

Planck satellite, in the 2010s, these

temperature fluctuations are observed to appear on all scales, and

they correspond to density fluctuations in the early Universe.

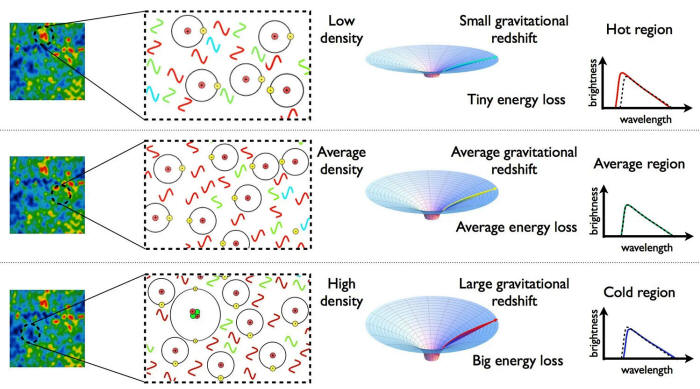

The link is because of gravitation, and the fact

that within general relativity, the presence and concentration of

matter-and-energy determines the curvature of space.

Light has to travel from the region of space

where it originates to the observer's "eyes," and that means:

-

the overdense regions, with more

matter-and-energy than average, will appear

colder-than-average, as the light must "climb out" of a

larger gravitational potential well,

-

the underdense regions, with less

matter-and-energy than average, will appear

hotter-than-average, as the light has a

shallower-than-average gravitational potential well to climb

out of,

-

...and that the average density regions will

appear as an average temperature: the mean temperature of

the cosmic microwave background...

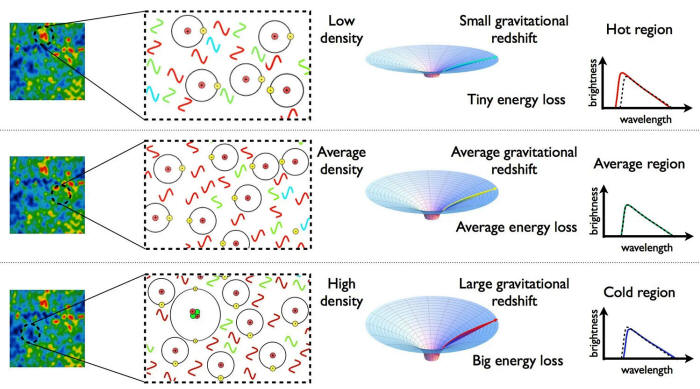

Credit: E. Siegel

Beyond the

Galaxy

|

Regions of space that are slightly denser than average

will create larger gravitational potential wells to

climb out of, meaning the light arising from those

regions appears colder by the time it arrives at our

eyes.

Vice versa, underdense regions will look like hot

spots, while regions with perfectly average density will

have perfectly average temperatures. |

But where did these imperfections come from, initially?

These temperature imperfections that we observe

in the Big Bang's leftover glow come to us from an epoch that's

already 380,000 years after the start of the hot Big Bang, meaning

they've already experienced 380,000 years of cosmic evolution.

The story is quite different, depending on which

explanation you turn toward.

According to the "singular" Big Bang explanation,

the Universe was

simply "born" with an original set of imperfections, and these

imperfections grew and evolved according to the rules of

gravitational collapse, of particle interactions, and of radiation

interacting with matter, including the differences between normal

and dark matter.

According to the inflationary origin theory, however, where the hot

Big Bang only arises in the aftermath of a period of cosmic

inflation, these imperfections are seeded by quantum fluctuations -

that is, fluctuations that arise due to the inherent

energy-time uncertainty relation in

quantum physics - that occur during the inflationary period:

when the Universe is expanding exponentially...

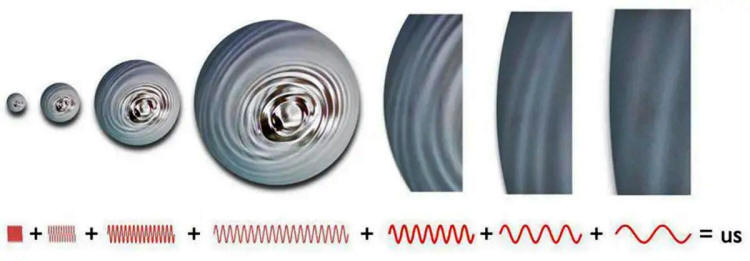

These quantum fluctuations, generated on the

smallest scales, get stretched to larger scales by inflation, while

newer, later-time fluctuations get stretched atop them, creating a

superposition of these fluctuations on all distance scales.

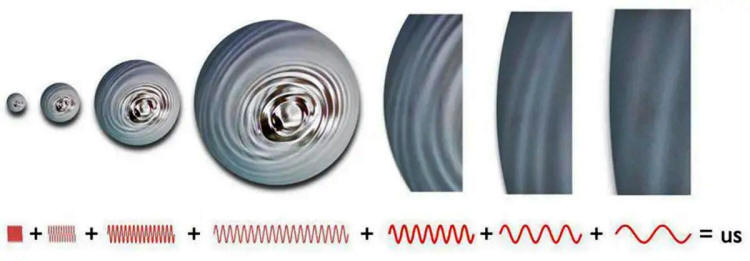

Credit: E. Siegel

Beyond the

Galaxy

|

The

quantum fluctuations that occur during inflation do

indeed get stretched across the Universe, and later,

smaller-scale fluctuations get superimposed atop the

older, larger-scale ones.

These field fluctuations cause

density imperfections in the early Universe, which then

lead to the temperature fluctuations we measure in the

cosmic microwave background, after all the interactions

between dark matter, normal matter, and radiation occur

prior to the formation of the first stable, neutral

atoms. |

These two pictures are conceptually different, but the reason

they're interesting to astrophysicists is that each picture leads to

potentially observable differences in the types of signatures we'd

observe.

In the "singular" Big Bang picture, the types of

fluctuations that we'd expect to see would be limited by the speed

of light:

the distance that a signal - gravitational or

otherwise - would have been allowed to propagate if it were

moving at the speed of light through the expanding Universe that

began with a singular event known as the Big Bang.

But in a Universe that underwent a period of

inflation prior to the start of the hot Big Bang, we'd expect there

to be density fluctuations on all scales, including on scales larger

than the speed of light, which could have allowed a signal to travel

since the start of the hot Big Bang.

Because inflation essentially "doubles" the size

of the Universe in all three dimensions with each

tiny-fraction-of-a-second that passes, fluctuations that occurred a

few hundred fractions-of-a-second ago are already stretched to a

scale larger than the presently observable Universe.

Although later fluctuations superimpose themselves atop the older,

earlier, larger-scale fluctuations, inflation allows us to start the

Universe off with ultra-large-scale fluctuations that shouldn't

exist in the Universe if it began with a Big Bang singularity

without inflation.

Credit: E. Siegel; ESA/Planck and

the DOE

NASA/NSF

Interagency Task Force on CMB research

|

The

quantum fluctuations inherent to space, stretched across

the Universe during cosmic inflation, gave rise to the

density fluctuations imprinted in the cosmic microwave

background, which in turn gave rise to the stars,

galaxies, and other large-scale structures in the

Universe today.

This is the best picture we have of how

the entire Universe behaves, where inflation precedes

and sets up the Big Bang.

Unfortunately, we can only

access the information contained inside our cosmic

horizon, which is all part of the same fraction of one

region where inflation ended some 13.8 billion years

ago. |

In other words,

the big test that one can perform is to examine the

Universe, in all its gory details, and look for either the presence

or absence of this key feature:

what cosmologists call

super-horizon

fluctuations.

At any moment in the Universe's history, there's

a limit to how far a signal that's been traveling at the speed of

light since the start of the hot Big Bang could've traveled, and

that scale sets what's known as the

cosmic horizon.

-

Scales that are smaller than the horizon,

known as sub-horizon scales, can be influenced by physics

that's occurred since the start of the hot Big Bang.

-

Scales that are equal to the horizon,

known as horizon scales, are the upper limit to what

could've been influenced by physical signals since the start

of the hot Big Bang.

-

And scales that are greater than the

horizon, known as super-horizon scales, are beyond the limit

of what could've been caused by physical signals generated

at or since the start of the hot Big Bang.

In other words,

if we can search the Universe for

signals that appear on super-horizon scales, that's a great way to

discriminate between a non-inflationary Universe that began with a

singular hot Big Bang (which shouldn't have them at all) and an inflationary Universe that possessed an inflationary period prior to

the start of the hot Big Bang (which should possess these

super-horizon fluctuations).

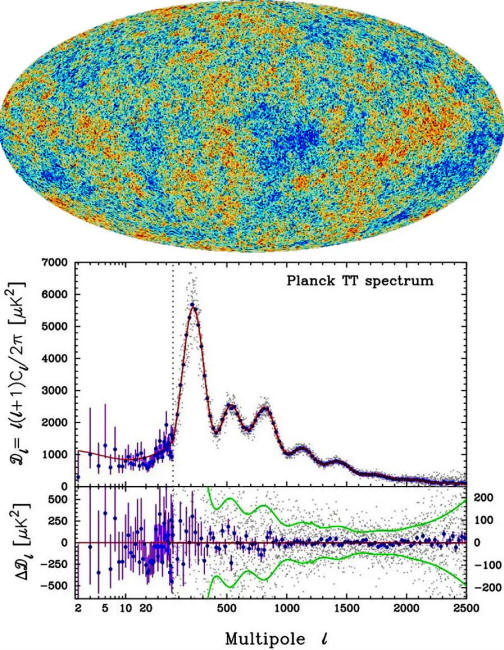

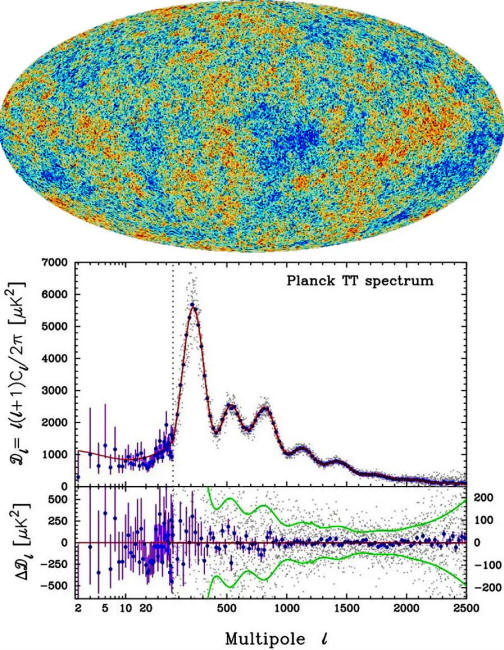

Credit: ESA and the Planck

Collaboration

|

The

fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background were

first measured accurately by COBE in the 1990s, then

more accurately by WMAP in the 2000s and Planck (above)

in the 2010s.

This image encodes a huge amount of

information about the early Universe, including its

composition, age, and history.

The fluctuations are only

tens to hundreds of microkelvin in magnitude.

On large

cosmic scales, the error bars are very large, as only a

few data points exist, highlighting a large inherent

uncertainty. |

Unfortunately, simply looking at a map of temperature fluctuations

in the cosmic microwave background isn't enough, on its own, to tell

these two scenarios apart.

The temperature map of the cosmic microwave

background can be broken up into different components, some of which

occupy large angular scales in the sky, and some of which occupy

small angular scales, as well as everything in-between.

The problem is that fluctuations on the largest scales have two

possible causes.

They could be created from the fluctuations that

arose during an inflationary period, sure.

But they could also be

created simply by the gravitational growth of structure in the

late-time Universe, which has a much larger cosmic horizon than the

early-time Universe.

For example,

if all you have is a gravitational potential well for a

photon to climb out of, then climbing out of that well costs the

photon energy; this is known as

the Sachs-Wolfe effect in physics,

and occurs for the cosmic microwave background at the point at which

the photons were first emitted.

However,

if your photon falls into a gravitational potential well

along the way, it gains energy, and then when it climbs back out

again on its way to you, it loses energy.

If the gravitational imperfection either grows or

shrinks over time, which it does in multiple ways in a gravitating

Universe filled with dark energy, then various regions of space can

appear hotter or colder than average based on the growth (or

shrinkage) of density imperfections within it.

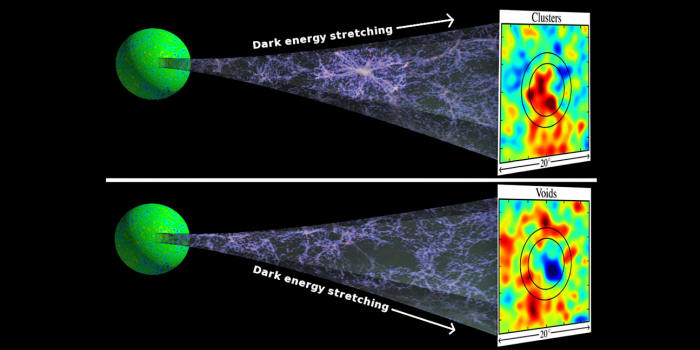

This is known as

the integrated Sachs-Wolfe effect.

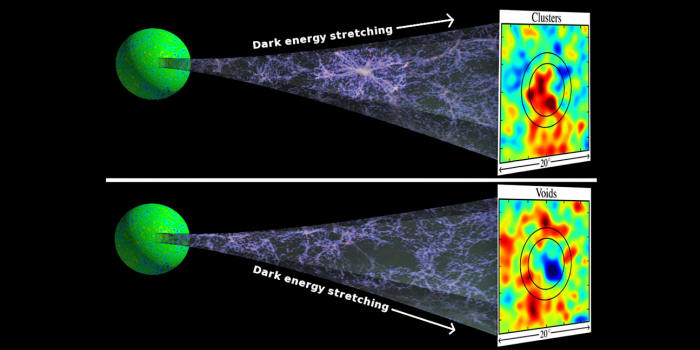

Credit: B.R. Granett et al., ApJ,

2008

|

At

late times, photons fall into gravitational structures

like rich clusters or sparse voids, and then leave

again.

However, matter can flow in or out of these

structures, and the expansion of the Universe can change

the strength of that potential during the time a photon

traverses it, creating a relative redshift or blueshift

owing to what's known as the integrated Sachs-Wolfe

effect. |

So when we look at the temperature imperfections in the cosmic

microwave background and we see them on these large cosmic scales,

there isn't enough information there, on its own, to know whether:

-

they were generated by the Sachs-Wolfe

effect and are due to inflation

-

they were generated by the integrated

Sachs-Wolfe effect and are due to the growth/shrinkage

of foreground structures

-

they're due to some combination of the

two

Fortunately, however, looking at the temperature

of the cosmic microwave background isn't the only way we get

information about the Universe; we can also look at the polarization

data of the light from that background.

As light travels through the Universe, it interacts with the matter

within it, and with electrons in particular. (Remember, light is an

electromagnetic wave!)

If the light is polarized in a radially-symmetric

fashion, that's an example of an E-mode (electric) polarization.

If

the light is polarized in either a clockwise or counterclockwise

fashion, that's an example of a B-mode (magnetic) polarization.

Detecting polarization, on its own, isn't enough

to show the existence of super-horizon fluctuations, however.

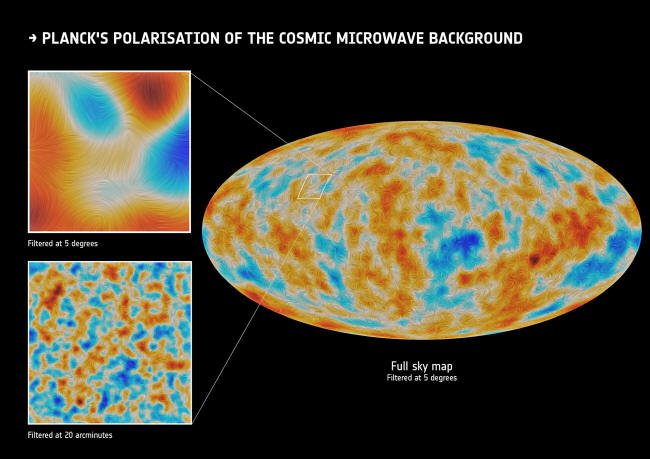

Credit: ESA and the Planck

Collaboration, 2015

|

This

map shows the CMB's polarization signal, as measured by

the Planck satellite in 2015.

The top and bottom insets

show the difference between filtering the data on

particular angular scales of 5 degrees and 1/3 of a

degree, respectively.

While temperature data, alone, can

demonstrate that the CMB is of cosmic nature, the

polarization signal gives us key pieces of information

relevant to the details of cosmic inflation. |

What you need to do is perform a correlation analysis:

between the polarized light and the

temperature fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background and

correlate them on the same angular scales as one another.

This is where things get really interesting,

because this is where observationally looking at our Universe allows

us to tell the "singular Big Bang without inflation" and the

"inflationary state that gives rise to the hot Big Bang" scenarios

apart...!

-

In both cases, we expect to see

sub-horizon correlations, both positive and negative ones,

between the E-mode polarization in the cosmic microwave

background and the temperature fluctuations within the

cosmic microwave background.

-

In both cases, we expect that on the

scale of the cosmic horizon, corresponding to angular scales

of about 1 degree (and a multipole moment of about l = 200

to 220), these correlations will be zero.

-

However, on super-horizon scales, the

"singular Big Bang" scenario will only possess one large,

positive "blip" of a correlation between the E-mode

polarization and the temperature fluctuations in the cosmic

microwave background, corresponding to when stars form in

large numbers and reionize the intergalactic medium.

The "inflationary Big Bang" scenario, on

the other hand, includes this, but also includes a series of

negative correlations between the E-mode polarization and

the temperature fluctuations on super-horizon scales, or

scales between about 1 and 5 degrees (or multipole moments

from l = 30 to l = 200).

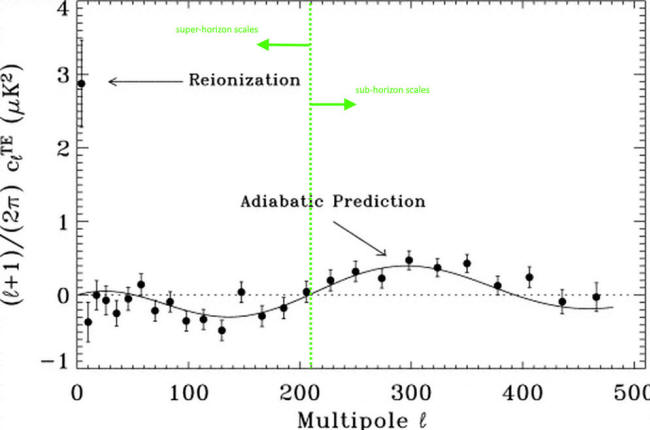

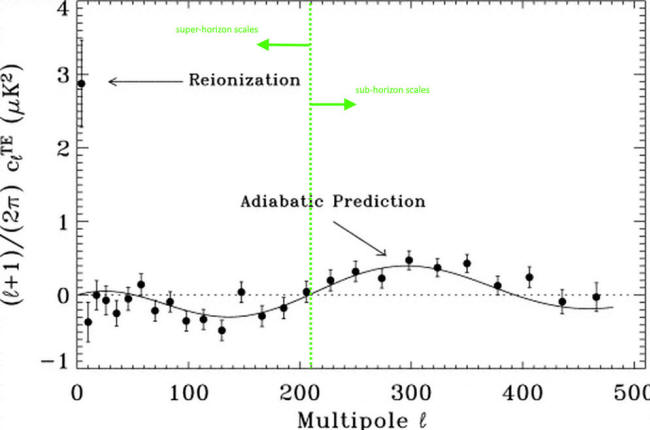

Credit: A. Kogut et al., ApJS,

2003;

annotations by

E. Siegel

|

This

2003 WMAP publication is the very first scientific paper

to show the evidence for super-horizon fluctuations in

the temperature-polarization correlation (TE

cross-correlation) spectrum.

The fact that the solid

curve (and the data), and not the dotted line, is

followed to the left of the annotated green dotted line

is very difficult to overlook, and represents extremely

strong evidence for super-horizon fluctuations: evidence

for inflation. |

What you see, above, is the very first graph,

published by the WMAP team in 2003,

a full 20 years ago, showing what cosmologists call the TE

cross-correlation spectrum:

the correlations, on all angular scales, that

we see between the E-mode polarization and the temperature

fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background.

In green, I've added the scale of the cosmic

horizon, along with arrows that indicate both sub-horizon and

super-horizon scales.

As you can see, on sub-horizon scales, the

positive and negative correlations are both there, but on

super-horizon scales, there's clearly that big "dip" that appears in

the data, agreeing with the inflationary (solid line) prediction,

and definitively not agreeing with the non-inflationary, singular

Big Bang (dotted line) prediction.

Of course, that was 20 years ago, and the WMAP satellite was

superseded by the Planck satellite, which was superior in many ways:

it viewed the Universe in a greater number of

wavelength bands, it went down to smaller angular scales, it

possessed a greater temperature sensitivity,

it included a dedicated polarimetry

instrument, and it sampled the entire sky more times,

further reducing the errors and uncertainties.

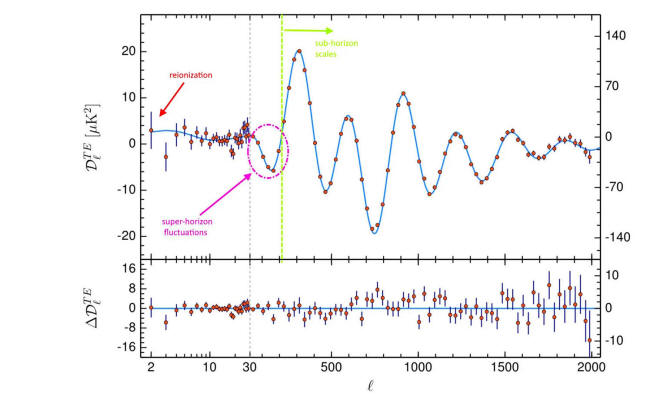

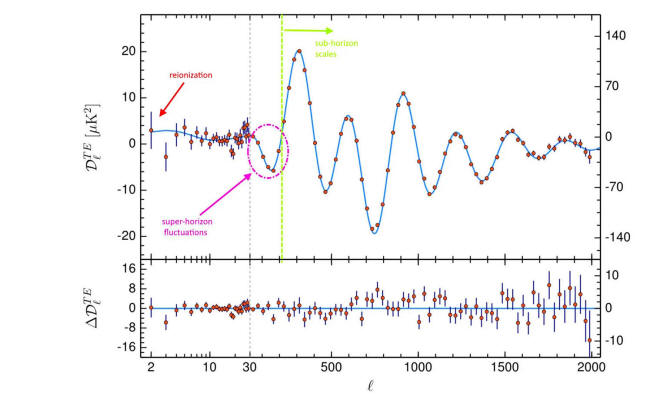

When we look at the final (2018-era) Planck TE

cross-correlation data, below, the results are breathtaking.

Credit: ESA and the Planck

collaboration;

annotations by

E. Siegel

|

If

one wants to investigate the signals within the

observable Universe for unambiguous evidence of

super-horizon fluctuations, one needs to look at

super-horizon scales at the TE cross-correlation

spectrum of the CMB.

With the final (2018) Planck data

now in hand, the evidence is overwhelmingly in favor of

their existence, validating an extraordinary prediction

of inflation and flying in the face of a prediction

that, without inflation, such fluctuations shouldn't

exist. |

As you can clearly see, there can be no doubt that

there truly are super-horizon fluctuations

within the Universe, as the significance of this signal is

overwhelming.

The fact that we see super-horizon fluctuations,

and that we see them not merely from reionization but as they are

predicted to exist from inflation, is a slam dunk:

the non-inflationary, singular Big Bang model

does not match up with the Universe we observe.

Instead, we learn that we can only extrapolate

the Universe back to a certain cutoff point in the context of the

hot Big Bang, and that prior to that, an inflationary state must

have preceded the hot Big Bang.

We'd love to say more about the Universe than that, but

unfortunately, these are the observable limits that we're stuck

with:

fluctuations and imprints on larger scales

leave no effect on the Universe that we can see.

There are other tests of inflation that we can

look for as well:

a nearly scale-invariant spectrum of purely

adiabatic fluctuations, a cutoff in the maximum temperature of

the hot Big Bang, a slight departure from perfect flatness to

the cosmological curvature, and a primordial gravitational wave

spectrum among them.

However, the super-horizon fluctuation test is an

easy one to perform and one that's completely robust.

All on its own, it's enough to tell us that the Universe didn't

start with the hot Big Bang, but rather that an inflationary state

preceded it and set it up.

Although it's generally not talked about

in such terms, this discovery, all by itself, is easily a

Nobel-worthy achievement.

|