|

by Katyanna Quach

June 30,

2021

from

TheRegister Website

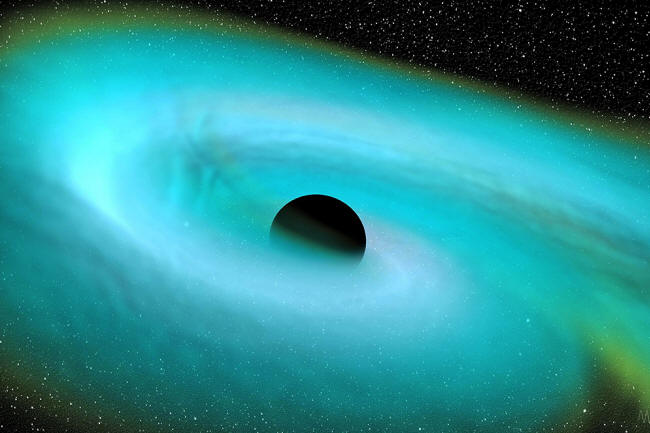

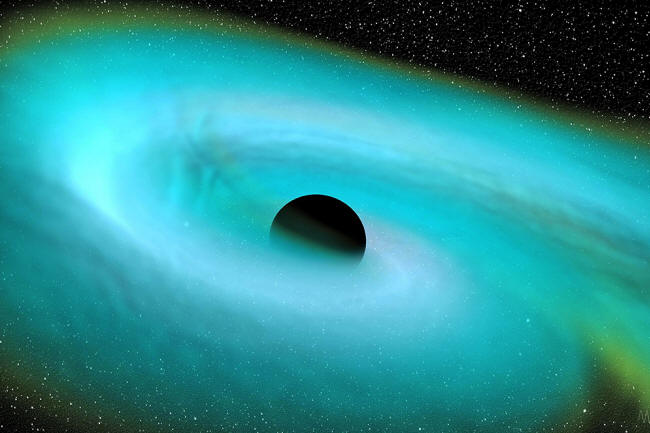

Image from a MAYA collaboration numerical

relativity simulation of an NSBH binary merger,

showing the disruption of the Neutron Star.

Credit: Deborah Ferguson (UT Austin),

Bhavesh Khamesra (Georgia Tech),

and Karan Jani (Vanderbilt)

You wait ages

for a neutron

star

and black hole

to collide,

then two pairs

come along

at once...

Gravitational wave detectors have reportedly spotted the merger of a

black hole and a

neutron star - not once but twice in the same month.

This is the first time

scientists have been able to confirm the detection of the merger of

a black hole and neutron star, too.

Although several

gravitational wave events have been detected since America's

Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) made

the first

gravity wave discovery in 2015,

they have always involved collisions between objects of the same

type, such as two black holes smashing into each other, or two

neutron stars.

These latest discoveries, however, are the result of odd pairings: a

black hole with nine times the mass of our Sun crashing into a

1.9-solar-mass neutron star, and a slightly smaller black hole

measuring six solar masses impacting with a 1.5-solar-mass neutron

star.

The cosmic prangs were announced on Tuesday by multiple teams

working with the

LIGO and

Virgo detectors in Louisiana, USA,

and Santo Stefano a Macerata, Italy, respectively.

As the LIGO and Virgo detectors become more and more finely tuned,

the detection of these merger events are expected to crop up like

buses:

none for ages, and

then many along at once.

These latest collisions

were detected ten days apart, on January 5, 2020, at 1624 UTC, and

January 15 at 0423 UTC.

The first event, the more energetic of the two and

involving the more massive bodies, was code-named

GW200105, and took place about 900

million light-years from Earth.

The second event,

referred to as

GW200115, was further away at about

one billion light-years away.

"We had long expected

to see a merger between a black hole and neutron star, but there

are many uncertainties that made it difficult to predict how

many of this pairing there are in our universe," Ryan Magee,

co-author of a paper (Observation

of Gravitational Waves from Two Neutron Star-Black Hole

Coalescences) published in The Astrophysical

Journal and a postdoctoral scholar at the California

Institute of Technology, told The Register.

"From these two detections, we can infer that, in a fixed volume

of space, there are a few more neutron star-black hole mergers

per year than black hole-black hole [ones], but not as many as

there are neutron star-neutron star mergers."

Previous attempts to

confirm a black hole-neutron star collision were unfruitful.

One signal detected in

April 2019 may have been skewed by noise, and another from August of

the same year is

still being debated.

Both black holes likely swallowed their neutron stars whole, leaving

no trace of light for the team to follow.

"These were not

events where the black holes munched on the neutron stars like

the cookie monster and flung bits and pieces about," Patrick

Brady, a professor at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and

spokesperson of the LIGO Scientific Collaboration,

said in a statement.

"That 'flinging

about' is what would produce light, and we don't think that

happened in these cases."

A merger between a

galactic void and the densest type of star probably occurs within a

billion light years of Earth about once a month, the team reckon.

"The detector groups

at LIGO, Virgo, and

KAGRA are improving their

detectors in preparation for the next observing run scheduled to

begin in summer 2022," Prof Brady added.

"With the improved

sensitivity, we hope to detect merger waves up to once per day

and to better measure the properties of black holes and

super-dense matter that makes up neutron stars."

|