|

by Robert Lea

a rotating supermassive black hole.

(Image

credit: Robert Lea - created with Canva) really do sit at the frontier of human understanding"...

The discovery came as the result of a new form of

"black hole archeology" that links black hole spins to the gas and

dust they have consumed to grow over 7 billion years of cosmic

history. The findings, courtesy of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) suggest a few things. For one, the early universe may have been more orderly than previously suspected.

And secondly, the growth of supermassive black holes through the merger chain of progressively larger and larger black holes (triggered as galaxies collide and merge) may be supplemented by the objects voraciously feasting on surrounding gas and dust.

Measuring Black Hole spin isn't easy

Despite being cosmic monsters that shape the

entire galaxies around them, supermassive black holes with masses

millions or billions of times that of the sun (and their more

diminutive stellar-mass counterparts) are overall quite simple.

As physicist John Wheeler wittily explained this lack of distinguishing features:

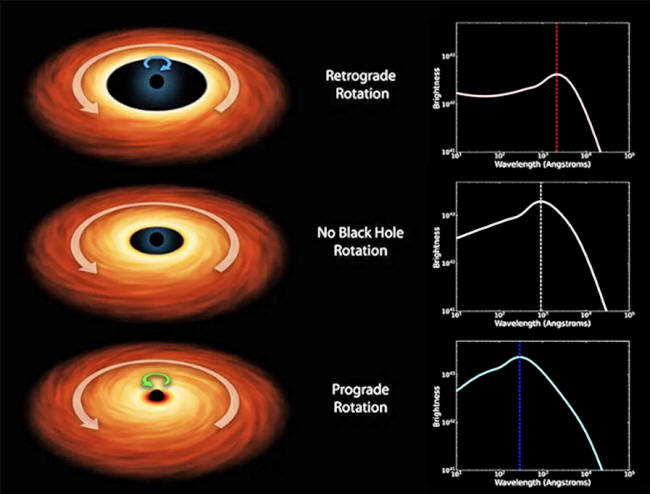

(Left) Artist's impressions of a black hole and its accretion disk with different spins. (Right) the corresponding multiwavelength spectrum that would be observed in each one. (Image credit: Left: NASA/JPL-Caltech Right: Logan Fries and the SDSS collaboration)

The speed at which a black hole spins is difficult to distinguish from the speed at which the surrounding flattened cloud of gas and dust - the accretion disk - rotates.

A Cosmic Fossil Record

The team tackled the challenging task of determining the spin of black holes using the SDSS's Reverberation Mapping project.

This project has been making extremely precise mass measurements for hundreds of black holes while also conducting detailed observations of the structures of the voids' accretion disks.

When material falls into the black hole, it also brings with it angular momentum - that rotation reveals details of a black hole's past diet.

An illustration of a supermassive black hole in the early cosmos. (Image credit: Robert Lea - created with Canva)

This "fossil record" can be decoded when scientists compare the observed rate of spin to what is predicted.

Currently, the favored model suggests supermassive black holes grow by mergers triggered when their home galaxies collide and merge.

Because these individual galaxies have their own rates of rotation and random orientation,

Given this, scientists expect that black holes should spin very slowly.

That isn't what this team discovered, however...

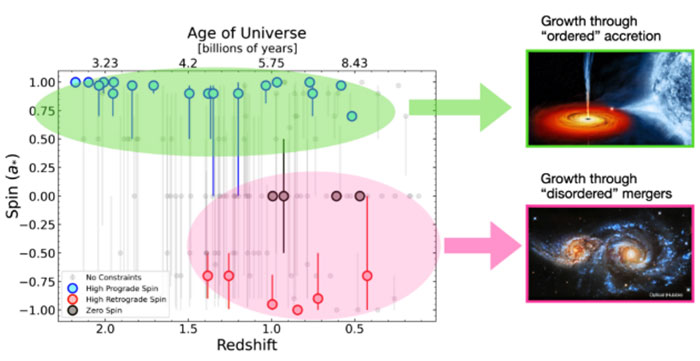

A graph of observed black hole spin over the history of the universe, from past to present running left to right. The thick colored dots represent the observed spins of black holes, blue shows rotation in the same direction as the accretion disk, gray shows little or no rotation, and red shows rotation in the opposite direction. The green oval shows what would be expected from black hole growth by smooth accretion; the pink oval shows what would be expected from mergers. (Image credit: Left: Logan Fries and the SDSS collaboration Top right: NASA, ESA, and The Hubble Heritage Team (STScI) Bottom right: NASA/CXC/M.Weiss)

Not only did this research reveal that many black holes are spinning more rapidly than expected, but it also showed that black holes in more distant galaxies spin even more quickly than those in the local universe.

This suggests the spin of black holes could build gradually over time.

One way that could happen is through the black hole's accumulation of angular momentum by its gradual accretion of dust and gas.

Researchers could further test this idea and verify these results using observations from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which, in its three years of operation, has been finding supermassive black holes from earlier and earlier epochs of the universe.

Fries presented the team's findings on Jan. 14 at the 245th meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) in National Harbor, Maryland.

|