|

by Joey Shapiro Key and Martin Hendry

June 2016

Volume 12 - Nature Physics

from

SCI-Hub Website

|

Joey Shapiro Key is Director of

Education and Outreach for the Center for Gravitational Wave

Astronomy at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, Brownsville,

Texas 78520, USA.

Martin Hendry is Head of the

School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Glasgow,

Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK.

E-mail:

jkey@phys.utb.edu;

martin.hendry@glasgow.ac.uk |

The announcement

confirming

the discovery of gravitational

waves

created sensational media

interest.

But educational outreach and

communication

must remain high on the agenda

if the general public is to

understand

such a landmark result.

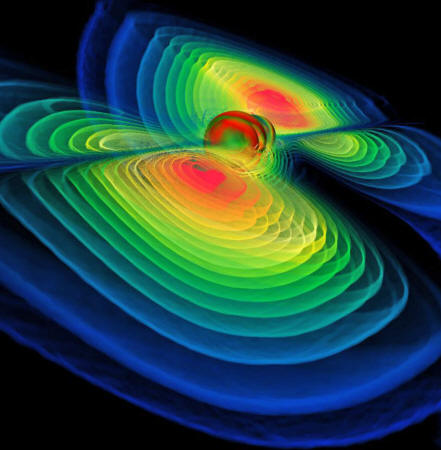

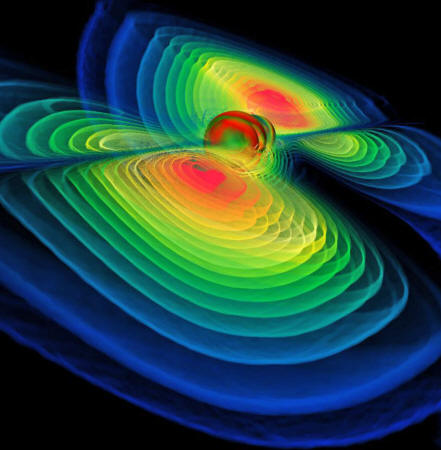

On 11 February 2016 the

LIGO Scientific Collaboration (LCS) and

Virgo collaboration (LSC and the

Virgo Collaboration are separate organizations, they cooperate

closely and are referred to collectively as "LVC"), announced the discovery of

gravitational waves

and the first observation of a binary black hole merger. 1

The physics community has been working

towards these discoveries since Einstein's theory of general

relativity predicted gravitational waves and black holes 100 years

ago. 2, 3

It is an especially salient example of

work that takes dedication and patience over generations of

scientists.

So,

-

How does the scientific

community share the excitement of this long-awaited

discovery with the world?

-

How can the importance of the

discovery be communicated to a public that is not familiar

with the details of the work?

-

And how can the entire history

of the field of gravitational wave astronomy be condensed to

maximize interest and impact for non-experts?

Modern modes of communication require

swift reactions, distilled messages, and new content backed up by

in-depth coverage of the human, historical and fundamental science

stories.

To assess the impact of the news of a

scientific discovery it is important to differentiate between public

excitement and public understanding. Efforts on both fronts are

valid and important but it is harder to evidence the latter: a

genuine increase in public understanding.

That said, we can surely agree that everyone should be able to

appreciate something about how important and exciting physics is,

regardless of their academic background, social demographic or

native language.

The discovery of

gravitational waves and the merger

of two black holes are awe-inspiring events, even for those who do

not have a deep understanding of general relativity.

Similarly, one can love a Mozart

symphony or a Renoir portrait without expertise in symphonic writing

or impressionist painting, and the beauty of Olympic athletics can

be admired by a worldwide audience, including a majority of people

who do not participate in any particular sport.

The Education and Public Outreach Working Group of the LVC helped to

shape the collaboration strategy for informing the world about our

scientific breakthrough.

As a group of professional scientists as

well as educators, outreach professionals, and students, we aimed to

assemble a range of resources designed for different levels and for

a variety of goals that would convey both the excitement and

importance of our discoveries and (as best we could) how those

discoveries had been made possible.

To what level of detail do we hope to have each individual engage

with our science and expand their understanding of the Universe?

With little or no mathematics we almost

always have to explain physics using analogies that are imperfect,

but that can convey core ideas.

For example, 'ripples in the fabric of

space-time' is the common analogy for gravitational waves, but what

does the 'ripple' actually refer to?

Waves on the surface of a

rubber sheet or trampoline do not 'stretch and squeeze' the

distances between points on the sheet, so the analogy doesn't work

to explain the effect of a passing gravitational wave on the LIGO

interferometers.

Indeed, physicists themselves were

confused about the nature of gravitational waves for 40 years, and

took an additional 60 years to build an experiment capable of

detecting them!

We therefore adopted a multi-level approach.

We developed accessible

resources using commonplace (if imperfect) analogies such as the

stretched rubber sheet, and simplified schematics such as our

interferometer animations, 4 designed to give even

the casual viewer some clear insight into what gravitational waves

are and how we detected them.

In parallel, we prepared in-depth

material designed to address more detailed questions about the

science and technology behind gravitational wave detection -

principally making this material available via our website.

5

A key example here was our science

summaries, 6 in-depth articles written without

technical language but conveying the essential scientific arguments

and conclusions presented in our detection papers.

Our products also included translations

of the press release into 18 languages, an educator guide for

teachers, new simulations and animations, and tutorials for using

the public LIGO data through the LIGO Open Science Center. 7

We also sought to promote our outreach efforts vigorously using

social media, formulating a comprehensive plan that would direct

followers to the very latest news, provide clear pathways to more

in-depth resources, and offer opportunities to engage directly with

us as LVC researchers.

These included, for example, an e-mail

address (question@ligo.org) that since February has attracted

hundreds of enquiries from across the globe, posing some highly

challenging and perceptive questions to the collaboration.

Finally, our strategy highlighted the importance of not just our

scientific breakthroughs, but also the scientific methodology that

underpinned them.

We emphasized three key messages in

particular.

-

Firstly, detecting gravitational

waves was extremely challenging and a quest that many had

thought impossible (in the words of LIGO Executive Director

Dave Reitze, it was the equivalent of the Apollo 'moonshot').

Thus our success was a triumph for the long-term vision and

investment of the National Science Foundation (NSF) and

other national funding agencies.

-

Secondly, we highlighted that

our discovery relied on the teamwork and cooperation of many

hundreds of scientists and engineers from dozens of

countries across the globe - mirroring the methodology of

many contemporary 'big science' projects.

-

And thirdly, to quote

Carl

Sagan, we conveyed the concept that "extraordinary claims

require extraordinary evidence".

The 5 month delay between our detection

and its announcement involved a huge amount of meticulous analysis,

leaving no stone unturned in the quest to convince ourselves that we

detected a real signal.

In other words, this was part and parcel

of the scientific process.

Box 1 - Making Waves about Gravitational

Waves

The worldwide response to the announcement that gravitational

waves had been discovered wasn't restricted to the mainstream

media.

The sheer breadth and depth of

interest it generated was a testimony to the importance of the

result:

-

Newspaper and television

news coverage of the gravitational wave detection

included front page articles in the

-

New York Times, and on the

CNN and BBC websites. A total of 961 newspaper front

pages from 12 February featured the discovery according

to Newseum, which included it on their list of dates in

2016 deemed to be of historical significance - and it

was the only positive historical news day selected in

the past 6 months. 8

-

Members of the US Congress

met with leaders from the NSF and LIGO in a hearing that

has been lauded as a bipartisan show of support.

-

The LIGO Scientific

Collaboration Facebook page top post reached 665,000

people, with 15,000 likes and 2,800 shares. From 8

February to 8 March the page reached 1.5 million people,

7,300 shares, 42,400 reactions, and gained 8,700 new

followers.

-

Caltech media reported 70

million aggregate impressions on all tweets using the #gravitationalwaves,

#LIGO, and #EinsteinWasRight hashtags.

-

The @LIGO Twitter top tweet

had 639,000 impressions, 4,116 retweets, and 2,996

likes. From 8 February to 8 March the account had 4.7

million impressions and gained 19,200 new followers.

The top LIGO Twitter mention

was from President Obama, who tweeted as @POTUS:

"Einstein was right!

Congrats to @NSF and @LIGO on detecting

gravitational waves - a huge breakthrough in how we

understand the Universe", with 80,000 engaged, 9,500

retweets, and 21,000 likes.

-

The PhD Comics on

gravitational waves has had 1.5 million views. 9

-

Brian Greene appeared on The

Late Show with Stephen Colbert to discuss LIGO and the

discovery of gravitational waves. His appearance has had

over 2.2 million views on YouTube. 10

-

In a YouGov survey conducted

in the UK, a third of people polled thought that the

discovery mattered a 'fair amount' or 'a great deal'.

-

Our Reddit Ask Me Anything

(AMA) session on 12 February provided 923 comments, with

LVC scientists answering more than 90% of the questions

asked 11 and sparked a separate thread

discussing the LVC AMA on reddit.com/r/bestof.

-

The NASA Astronomy Picture

of the Day featuring the gravitational wave discovery

12 had over a million views over 11-16

February, and was translated into over 20 languages on

external mirror sites.

-

Poet and non-scientist Missy

Assink 13 read her original poem

GW150914 or a Love Story Between Two Black Holes at

Spoken Word Paris in March 2016. 14

Our efforts to communicate the importance of the discovery have

certainly helped to build public interest in physics research (see

Box 1 above). And generating excitement is undoubtedly

the first step towards promoting understanding and awareness among

the general public.

Although we can never measure the exact impact

this discovery will have on society, it's clear that there is a wave

of

new physics fans across the globe.

References

-

Abbott, B. P. et al. Phys. Rev.

Lett. 116, 061102 (2016)

-

Einstein, A. & Sitzungsber, K.

Preuss. Akad. Wiss. 1, 688 (1916)

-

Einstein, A. & Sitzungsber, K.

Preuss. Akad. Wiss. 1, 154 (1918)

-

https://www.ligo.caltech.edu/video/ligo20160211v6

-

www.ligo.org

-

http://www.ligo.org/science/outreach.php

-

https://losc.ligo.org/about/

-

Discovery of gravitational waves

Newseum -

http://go.nature.com/nHTw7T

-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4GbWfNHtHRg

-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ajZojAwfEbs

-

https://www.reddit.com/r/IAmA/comments/45g8qu/we_are_the_ligo_scientific_collaboration_and_we/

-

http://apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap160211.html

-

https://about.me/missyassink

-

https://www.facebook.com/Spoken-Word-Paris-165517768215/

|