|

by Ramin Skibba of the winds created by a black hole

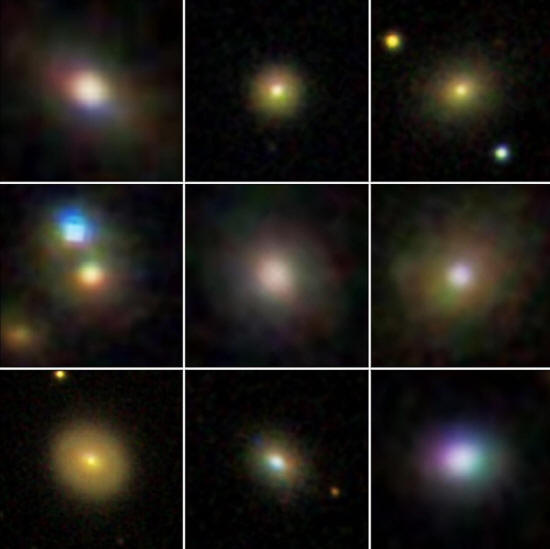

at the center of a galaxy. have been found to hide gas-spewing black holes...

That's the takeaway from a new study of so-called dwarf galaxies - galaxies that are so small and dim that astronomers only know about the ones relatively nearby.

What's more, these black holes are somewhat explosive - engines powering strong jets of gas and radiation that stifle the galaxies' growth.

Gabriela Canalizo and her colleagues found dwarf galaxies with black holes providing energetic feedback stronger even than they expected.

The research (AGN-Driven

Outflows in Dwarf Galaxies) has been submitted to The

Astrophysical Journal.

Astronomers find them

either by spotting the hard turns made by nearby stars, or by

catching the glow that appears when gas and stars fall in, creating

a radiation-spewing "active galactic nucleus" -

AGN.

Because they have few stars for astronomers to track, and little gas and dust to power active galactic nuclei, it was assumed that any black holes in dwarf galaxies would live up to their name and be too dark to find.

Not anymore...

The researchers started their search by combing through the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, which is essentially a huge map of the northern night sky collected over many years of observation.

They picked out 29 relatively close dwarf galaxies using two criteria.

They then used the giant Keck telescope in Hawaii for follow-up observations.

Upon taking a closer look at the 29 candidate galaxies, they found 13 that showed evidence of oxygen ions missing two electrons - a telltale signal of an active galactic nucleus.

They also determined that

gas in these 13 galaxies was flowing out at speeds of up to 1,000

kilometers per second - fast enough for at least some gas to

overcome the gravitational pull of the galaxy and erupt into

intergalactic space.

During this process,

other stars die in supernova explosions, which can disrupt the star

formation process and eject gas from the galaxy.

that

hide massive black holes in their cores.

But these massive black holes, in the form of active galactic nuclei, are far more powerful growth disruptors.

The research also affects the standard view of how the largest black holes in the universe came to exist.

Many astrophysicists, including Jillian Bellovary, think that such supermassive black holes grow when entire galaxies smash into each other, leading their central black holes to collide and form bigger ones.

If dwarf galaxies

host large black holes, collisions between these smaller galaxies

might eventually lead to black holes of the supermassive variety,

which can have the mass of billions of Suns.

It's designed to measure gravitational waves emanating from the impacts of smaller black holes, like those now known to inhabit dwarf galaxies.

Its planned launch is

still 15 years away.

|