|

by Carlo Barbera

July 24, 2007

from

ThePaganFiles Website

The origins

While many European populations are linked to their original

homeland because of historical reasons or the archaeological

evidence of migrations that occurred in remote times, the origin of

the Basque people were and still remain shrouded in mystery.

Something like two million and half Basques live nowadays along the

Western range of the Pyrenees in a territory on the border between

France and Spain.

Euskal Herria (the Basque name of the country) is formed by seven

provinces:

-

Bizkaia, Gipuzcoa, Araba and Navarra in Spain

-

Lupurdi,

Bassa Navarra and Zuberoa in France

Though these provinces straddle the

geo-political boundaries of the two European countries, their are

independent from an ethnic as well as a linguistic point of view.

The Basques think of themselves as the

original, prehistoric inhabitants of what is, today, Spanish

territory. Some scholars think that the Basques may indeed be the

descendants of the Cro-Magnon populations that occupied the area in prehistorical times and that made the famous rock paintings and

graffiti discovered inside many caves in this territory.

Physical anthropologists think that

modern Basques and ancient Cro-Magnon men share many characteristics

and physical traits.

On the basis of our current knowledge, the most ancient remains

discovered in the land today occupied by the Basques date to the

Lower Palaeolithic period and can be assigned to 200.000 - 100.000

BCE. The evidence is based on lithic and pointed tools in sandstone,

quartz, silica and basalt, discovered in sites along the coast and

in riverine settlements.

The origin of the language called Euskara, spoken by the Basques, is

unknown. It is a pre Indo-European language, totally unique, that

shares only a few analogies with Caucasic and Berber dialects. The

Basques call themselves Euskaldun, from Euskara "Basque language"

and dun "somebody who speaks". Modern linguistics try to discover

the age of this language by investigating its most ancient root

words.

For example, the word axe, haizkolari, derives from the root-word

haitz, which means stone or rock. This has lead many to think that

it may be a linguistic reference to Neolithic stone tools.

In his studies, the abbot Dominique Lahetjuzan (1766-1818) came to

the conclusion that the Basque language was the language spoken in

the Garden of Eden. He showed how the names of the main chapters of

the Book of Genesis were all Basque in origin and had their

appropriate, specific meaning. For his theories, the abbot has been

called one of the strangest characters of the theological era.

In 1825, the French abbot Diharce De

Bidassouet wrote in his "History of the Cantabrians" that Basque was

the original language spoken by God, a statement for which the abbot

was soundly ridiculed.

At about the same period, the Basque priest

Erroa stated that Basque was the language spoken in the Garden of

Eden. His colleagues thought he was a lunatic, but Erroa was so

deeply convinced of being right in his hypothesis that he caught the

attention of the Bishop of Pamplona: he, conversely, directed his

appeals to the Chapter of the Cathedral of Pamplona.

The ecclesiastical institution

considered Erroa's theories and, after many months of deliberations,

established that Erroa was right and publicly supported his theory.

However, in a short time all the reports and the registry containing

the ecclesiastical deliberations disappeared mysteriously.

Many studies on the Basque people stress how deeply they are

different and separated from other cultures. However, if we look

closely we can see this is not completely true. In ancient times the

Basques were known to the Greeks, who called them Ouaskonous (the

people of the he-goat), due to their habit of sacrificing goats to

their gods.

Later on, the Roman armies that passed

through Iberia reported to have been in contact with a population

they called Vascones.

The advent of

Kixmi

The expansion of Christianity in the land occupied by the Basques

was a very slow process. In the 9th century AD, in fact, in many

areas of the country there were still many Gentiles, i.e., Pagans

(the protagonists of a number of legends in which Gentile is often

the synonymous of a gigantic, wild man who has exceptional strength

and who lives hidden in the mountains, away from the local

communities).

However, the presence of groups of

Christianized people in certain localities from the 4th century AD

testifies that the Christian religion had already started to spread

in these areas since the beginning of the Christian era.

The mythological and folk lores will be deeply touched by the new

religion.

To exemplify that, it suffices to mention the legend of the

mysterious cloud. One day, in the vicinity of Ataun, a luminous

cloud coming from the East appeared in the sky. The Gentiles were

frightened. They asked an old man what was the meaning of that omen,

and he replied:

"Kixmi (Christ) has come. It is the end of our era,

throw me down a precipice".

This was done and then, followed by the

cloud, they tried to hide themselves beneath a large stone: the

refuge turned to be their grave.

Traces of this lost world can be found in the prehistory of the

Basque people: when ordered chronologically, these traces could

offer an idea of some of the most relevant traits of the Basque

original religious beliefs. A lot, however, can be reconstructed

analyzing the ethnographic data, the rites and the local folklore of

the Basque people.

The Pyrenees are dotted with sacred sites: caves, springs, wells,

valleys and mountain peaks. The mountains and the valleys were

thought to be the abodes of divinities and Genies: the earth was

believed to contain beautiful landscapes and green valleys hidden to

mortals. The most famous of all these sites is probably a plain

named Akelarre in the province of Navarra. The name comes from

aker,

he-goat and larre, pasture.

For hundred of years, this place was

connected to witchcraft and it has been probably chosen as the place

where to celebrate ancient rituals and sacrifices. The Church has

eradicated any information related to the pagan religion of the

Basques, and has even denied the existence of such rituals. However,

the Greek geographer Strabo reports beyond doubt that sacrificing

goats was a ritual crucial in the religious beliefs of the

Ouaskonous.

Due to the many mountains which characterize the Basque landscape,

the Romans - and later on the Arabs, Spaniards and French - were not

able to gain full control over the region. The Romans occupied only

portions of the Basque land and imposed on them Roman law, but they

did not succeed in subjugating completely the Basque people.

It seems that the Basques have

assimilated in their own culture only few foreign words and customs:

they have been the last of all Western European people to be

converted to Christianity. For centuries, the Christian missionaries

and their new religion were ignored by a vast portion of the Basque

people, who preferred to practice their traditional religion, full

of magical beliefs. In the 14th century the number of Basques

converted to Christianity had raised sensibly, but until the 17th

century the non-Christian living in the area were still considerably

many.

In 1609, a controller sent from Bordeaux to check the state of the

Christian church in the Basque territory under French rule reported

that Witches Sabbath were often held in the churches themselves,

with the approval, if not the participation, of the local priest.

The French controller was shocked to see how sympathetic were the

local Basque priests towards the old, pagan religion.

The majority of the population still

practiced a religion which was a mixture of Paganism and

Christianity. Such reports provoked strong reactions in France and

in Spain which led to the systematic destruction of the Basque

religion and culture. In this way

the Catholic Church was able to

reach the goal which the Romans and the Arabs had missed: full

control over the Basque people.

Altogether, 2000 people were first accused of witchcraft and then

executed: something like 50.000 people witnessed the trials, which

were public and held in open spaces to facilitate the audience.

Pope Gregory IX instituted papal Inquisition in 1231 against heresy.

In 1478 Pope Sixtus IV authorized the Spanish Inquisition to fight

Jewish and Moslem apostasy. In 1483 he nominated the person who

would organize the Inquisition in all the regions of Spain. This was

the great inquisitor Tomas de Torquemada.

A hunting season was declared against women, especially those that

gathered herbs, obstetricians, widows and spinsters. It has been

estimated that 9 million people, above all women, were burnt or

hanged in Europe at that time.

It appears that Franciscans participated in these trials against

witchcraft helping the gathering and the building up of proofs.

They were particularly busy spying potential witches and denouncing

them to the authorities. They tortured women obtaining from them

false confessions.

At Logrono many people were tortured until they admitted anything

they were ordered to say by the monks. It is recorded that one of

the tortured women, Mariquita de Atauri, after she had denounced

while being tortured, a great many innocent people she killed

herself by throwing herself in the river near her house and drowning

. When the Inquisition was established in 1231, it was the

Dominicans who were in charge of the organization and killing of

heretics.

The

Inquisition and the

Dominicans concentrated themselves on the

Alps of northern Italy. The use of torture was officially authorized

by pope Innocent IV in 1252.

The Jesuits, many of whom were Basques like their founder Ignatius

de Loyola, don't seem to have taken part in the witch hunting but on

the contrary, it seems that they acted as mediators and translators

with the local population.

Maybe it was the Basque Jesuits who

defended their ancient language that was, together with the Basque

culture, one of the objectives of the Inquisition as it later was

that of Francisco Franco from 1930 onwards.

Basque

Pantheon

With the arrival of Christianity there also came the destruction of

much knowledge of various rituals and magical arts that were common

to all the valleys of Euskal Herria. Fortunately the Basques have a

strong oral tradition that is celebrated even today with songs and

competitions among storytellers. There is still a vast collection of

ancient myths and legends although many of them have never been

translated from Euskara.

According to the Basques there is a duality of beings and of worlds:

-

on the one side the natural world (berezko)

-

on the other the

supernatural one (aideko)

-

to operate in the first, one has to use

natural instruments

-

one enters the second through magic

The

magical means are many but they are all based on the ADUR, or

magical virtue, that links things with their representations.

Curses or birao are transmitted

thanks to adur, to the person or thing which is signaled: a

symbolic action towards an image emits its adur, that

operates at a distance. Names are sound images of things. According

to a popular Basque saying all that has a name exists "izena duen

gutzia omen da".

The main gods are Ortzi or Eguzki, the sun god, Ilargia or

Illargui, the moon goddess, Mari the earth goddess and Sugaar,

the god both of the earth and of the sky. Ortzi, also called Ost

or Eguzki, is the god of the sun, of the sky and of thunder

and is often compared to Jupiter, Zeus and Thor.

Ortzi, and its western equivalent Osti are the first elements in a

dozen words like "cloud storm", "thunder" and "dawn". For example

"rainbow" is Ortzadar (adar means horn) and "daylight"

is Orzargi (argi means light).

In many children rigmaroles there is mention of a female being,

scion of the earth (Lur). According to an old way of thinking, the

sun is born from the earth and goes back to it. It is believed that

sunlight is not liked by witches or by certain categories of Lamies,

as in a narration concerning a Lamia whose golden comb was stolen by

a shepherd. He was about to take it back when a ray of the rising

sun touched lightly the man's clothes .... "thank the sun" she told

him and retired in her cave.

Sun symbols are circles, swastikas, the flowers of thistles, very

frequent in Basque popular funerary art.

The dolmen culture with its dolmens oriented from east to west are a

proof of sun worship.

Unfortunately little remains of the god and of the myths and

knowledge of whatever ritual was celebrated to adore it.

The moon goddess Ilargia or Illargui appears in many myths and

legends. Because they are agriculturists and fishermen, the Basques

are very close to the moon cycles. Ilargia is the guardian of death;

lshe accompanies people on the way to the afterlife.

Ilargia regulates the world of the secret knowledge, of divination

and magic.

Illargui like the sun, is of a feminine gender; when she

appears on the eastern mountains one says:

"Illargui amandrea, zeruan ze iberri?"

(Lady, mother moon, what news do you bring us?).

Friday is sacred to her in the same way

as Thursday is sacred to the sky. According to an old belief, the

moon is the light of the dead and to die with a waxing moon is

considered a good omen for the afterlife. Sun and moon are children

of the earth where they both go back after their run in the sky.

In traditional tales it is said that the face of the earth is

unlimited in all directions and whoever wants to explore its borders

is destined to fail. The earth contains treasures hidden in caves

and mountains that often cannot be found because there are no

precise indications useful to find them and also because menacing

genies intervene and terrify those who seek the treasures and force

them to abandon the search. It is the habitual dwelling of souls, of

divinities and of most mythical beings some of which take on the

likeness of bulls, horses, goats and other animals.

The mythical world of the Basques is peopled by genies or divinities

that take on the shape of animals or of half human beings who live

inside caves.

Among these one is particularly important. This is Mari, an

anthropomorphic goddess, one of the most ancient chthonic female

deities.

Mari's husband is Maju, who also appears as a snake or Sugaar.

Apparently they live separately. Mari lives on earth and Maju/Sugaar

in the sea. This is for a good reason. When Maju and Mari

meet they produce violent rain storms with hail, thunder and

lightening.

A 16th century legend says that Mari is the founder of the

House of the Lords of Biscay.

The "Lady" or the "Dame", as Mari is often called, lives in the

regions of the deep, but also in grottoes and in precipices linked

with each other by subterranean conduits, Mari's shapes are diverse:

-

In the subterranean regions she takes on zoomorphic shapes

-

On the

surface instead she appears as a very beautiful lady elegantly

dressed who is combing her hair with a golden comb

-

Sometimes she

moves in the sky in a chariot drawn by horses or surrounded by

flames

-

She also appears like a flaming tree, a

white cloud, a rainbow, a gust of wind, a bird, a sickle made of

fire, moving from one mountain peak to another

-

Mari sometimes drives across the

sky her chariot drawn by four white horses or she rides a

white ram.

Like Persephone she is abducted by a bull. She

leads all subterranean genies. Sometimes she is not alone in her

dwelling but is surrounded by animal-genies or by young girls.

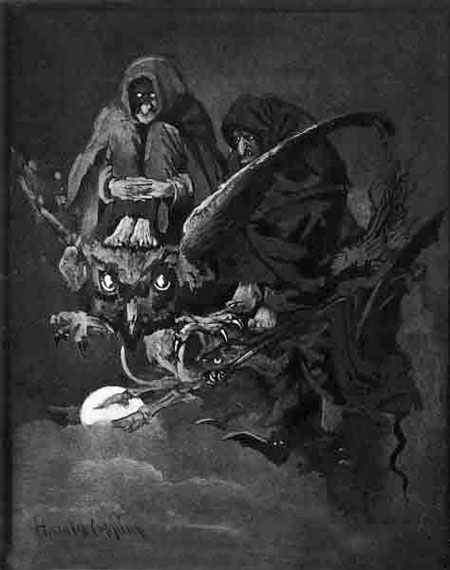

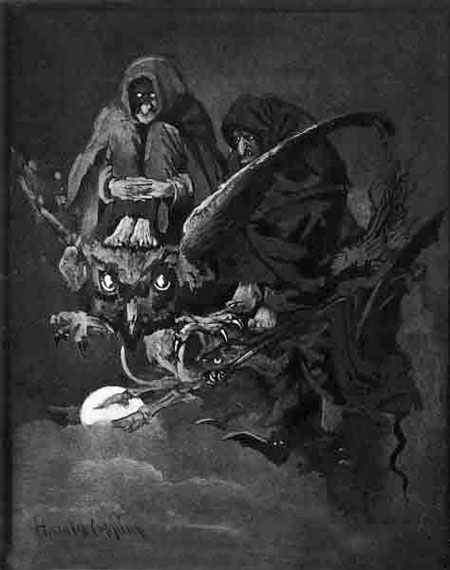

Many of her attributes are those characteristic of witches. A legend

narrates that Mari gave a piece of charcoal to one of her prisoners,

Catalina. The coal became pure gold. The goddess often changes her

dwelling place and for each of these places there is a corresponding

different character, as if the goddess was not one and the same but

a plurality of sister goddesses.

The caves where these live are often meeting places or witches

Akelarre. Like Mari, the witches have power over natural

phenomena.

The way the witches are called is Sorgin. Do witches exist?

"One cannot say that they exist, one cannot say that they do not

exist" according to a popular saying.

On the other hand the witches

themselves confirm their existence:

" No, we do not exist, yes we do

exist, we are fourteen thousand here", thus they answered some

women weavers at Eldauayen.

In many popular tales there is mention

of the abduction of people who disbelieved in them.

There are genie-witches and human-witches.

The first ones belong to Mari's cortege. They take on many of her

tasks and they build bridges and dolmen.

Men can also belong to the second category of witches but more often

they are women with a bad character whose interventions cause death

or infirmity.

The witches often transform themselves into cats, sometimes into

dogs or rams and they very often move about from one place to the

other by smearing themselves with an ointment and reciting a phrase

that says:

"Sasi guztien ganeti eta odei

guztien aizpiti" ( Above all the thorns and through all the

clouds).

Next to the subterranean and malevolent

genies there are some who are helpful (familiarrak), some

aquatic, rural, nocturnal, who fly, etc.

Between the world of the gods and that of man there is the Lord of

the Woods, the Basajaun. He is semi-divine and a strong,

hairy being with animal characteristics. Basajaun watches over the

forests and all wild creatures. He is a rural genie, the lord of the

woods or also the Wild Lord. He is considered to be the protector of

flocks.

When comes a storm he shouts warnings to

the shepherds; he prevent wolves from approaching flocks. He is the

first to have cultivated the earth. Human beings obtained the right

to cultivate the earth when a man won a bet with Basajaun. He stole

the seeds that Basajun was sowing and he came back to his peoples to

teach them how to produce food.

The Lamie or Laminak have a particular importance. They are genies

with a human shape although they have chicken, duck or goat feet.

In the coastal areas they are women with the lower part of their

bodies in the shape of a fish. They are not of a specific sex,

although they are mostly female genies. Some legends describe them

as small people that live underground.

Caves are their dwellings but they can also live near puddles and

river pools. They are in the habit of spinning with a spindle and a

distaff, of building bridges, dolmen and houses.

Lamies often appear with a golden comb, they willingly accept

offerings left by men on the window sill of houses; they fall in

love and are loved by human beings. If people enter per chance in

their dwellings they greet them kindly unless they are intrusive. In

that case they abduct them.

The duplicity of their nature is obvious. They can be beneficiary or

malevolent.

They can become extremely violent with those they abduct. They can

drink their blood and also eat the flesh of their victims.

The cycle of the Lamies has many links with that of the witches or

that of the Gentiles.

There are other deities, spirits, semi-divine beings like Intxitxu,

the invisible spirit that builds the Cromlechs, the mysterious stone

circles in the mountains that surround Oiartzun. Irelu is a

subterranean spirit that abducts whoever disturbs it. Its mysterious

footprints can be seen near the caves of Armontaitz and Malkorburu.

If one climbs the mountain called Ubedi you can hear its singing

mixed with the sound of the wind.

Near the caves of Balzola and Montecristo lives Erensuge, a terrible

snake that attracts people with its breath only to devour

them. In the area of Albistur and Zegama one can be frightened by

the echo of strange laments and by some sheep nearby that is running

away. It is Basajun that announces its presence and warns shepherds

that a storm is about to come.

Near the caves of Santimamine, Sagastigorri and Covairadea, look for

a cow that is completely red, a calf or a bull with ferocious eyes.

It's Beigorri, the guardian of many of Mari's abodes.

This animal is represented in many of

the paintings found in the caves of this region.

The "Etxe"

Basques are attached to house cults, etxe. A home is not only

the place of origin but a temple and a cemetery, a symbol and a

common centre for the living and the dead of a family. The

"etxekandere" or lady of the house is the main priestess of domestic

cults and she performs some rituals inherent with frequenting the

dead and the training of living people.

These traditions bear witness to the great respect that Basques have

for female roles, so much so that at the time of the fueros

the choice of the heir would fall on the first born, boy or girl,

contrary to the feudal laws that gave this prerogative only to male

descendants.

Before the arrival of Christianity the house was used as a family

burial place. Among the beliefs that are part of the religious

rituals there is that it is forbidden to turn around a house three

times. The Basque house was considered inviolable so much so that it

provided the right of refuge, and inalienable because it had to be

bequeathed whole and undivided to the members of a given family.

The souls of the dead were prayed to in the domestic cults, They

have a particular importance in Basque culture. According to a

widespread belief they appear in the shape of lightening, lights or

wind gusts, sometimes like shadows.

By night they often go back to

their etxe through subterranean passages.

Winter

festivals

According to tradition death does not break family links. The memory

of the dead lives in the magic rite of lighting thin candles, the

argizaiolak. The 1st of November is the day when the Winter

Festival begins. In places like Amezketa in Gipuzcoa the argizaiolak

light the tombs to keep alive the spirit of the dead.

The winter solstice has become part of the long Christmas

festivities.

A character named Olentzero announces

this season and seems to have originated in some pre-Christian

rituals. He is described as a simple coalman who was the first to

hear the good news. Maybe he is what remains of a character that was

linked with the ceremony of the lighting of the fire in a remote

past.

An interesting custom is that of "beating the Yule log ". The log is

brought to the house under a cloth blanket. The relatives and the

children say a prayer towards the log, then each of them beats the

log three times with a small branch. When the blanket is removed the

Yule log is exhibited together with candles and cakes.

The most important winter festival is Carnival. In many cities this

festivity is announced by strange processions during which the

participants are dressed like gypsies, a reminiscence of the time

when large tribes of gypsies used to come to the Basque carnivals.

In the province of Gipuzcoa the children of the two villages of

Amezketa and Abaltzisketa dance around all the houses to awaken the

generosity of their neighbors.

In the city of Lasarte-Oria the dance of

the witches 'Sorgin Dantza' is performed on the Sunday of Carnival..

Summer

festivals

While the ancient rituals of the winter solstice have almost

entirely been absorbed by Christianity, the traditions of the summer

solstice have remained strong and intact. The celebrations emphasize

the purification and the exaltation of summer and the sun. On the

night of the solstice practically in all the villages, city or farm,

a fire is lit.

In the countryside these can be seen on

the mountains and in front of the farms. In the towns they are lit

in the middle of squares or in a nearby field. A very popular custom

is that of jumping over the fire. In the country fires burning

branches are taken from the fire and dragged in the fields to cast

off any form of evil. The day after the summer solstice the markets

of the towns exhibit " lucky branches", pieces of wood that have not

been entirely burnt in the fires.

These are considered to be protective

against fires.

Conclusions

This is only a brief research on a very old and little known

Tradition. There is much to learn concerning the mythology and the

magic-spiritual practices of the Basque peoples. They contain the

archetypes from which all the knowledge of the world has emerged.

Within the deep knowledge of this people it seems that are hidden

the keys to open the secret doors of all the world Traditions.

The genetic and ethnic-cultural constitution of the Basques, the

remote origin of their language that seems to stem directly from the

ancestral memory of the earth and possibly from words, sparks of

life fallen from the gods of heaven, allow us to perceive a remote

enchanted garden, beyond the barriers of time, inhabited by

fantastic and wonderful creatures.

The attempts at erasing the signs of the Great Origin have not been

capable of shadowing the intact consciousness of reality that

appears in the folds of a world as modern as it is unreal and

ferocious.

The Lamies of the Baia still sing their melodious whispers in the

gusts of winds coming from the ocean and Mari still travels in the

starry sky of the nights in Euskal Herria, with her flaming chariot

leaving behind her on the top of the mountains tokens of her love

for her wonderful kingdom.

And in the streets of the villages, in the countryside and in the

towns one can still hear the agonizing laments for a Peace that has

never been acquired and of a Freedom forever negated to the

Euskaldunak people, those that speak the Basque language.

|