How are we going to feed 9 billion people by 2050?

The answer to this question - or the lack thereof - is one of the biggest issues in agriculture today. Experts estimate that we need to grow 60 percent more food than we currently produce.

And as a result, there is a push to constantly create more.

More miracle crops. More monocultures. More monocrops. More seeds. More food...

But are we missing the point?

Currently, in the U.S., almost half of our food - 40 percent of what we grow - ends up in the garbage. Globally, food waste is rising to 50 percent as developing nations struggle with spoilage and Western nations simply toss edible food away. Instead of turning our food system inside out to meet that 2050 deadline, why donít we simply waste less?

Do the math. If we just get better about using the food we grow, weíre already almost a quarter of the way there.

We need to start somewhere.

Letís start at the farm.

Farm to Table to Landfill

In Hackettstown, New Jersey, vegetable farmer Greg Donaldson leads informal tours around his fields to show visitors a large rotting pile of mostly edible produce.

The pile is a hub for perfectly good cucumbers (bent), strawberries (overripe but delicious), tomatoes (small blemishes), peaches (bruised) and garlic (split cloves). Stalks of broccoli, ears of corn, full heads of lettuce, eggplants, pears: Itís a perverse cornucopia, left to decay in the sun.

At the beginning of summer, the pile fits in a dumptruck bed; by fall, it needs multiple tractor-trailers to haul it away. The sight of so much wasted produce used to eat at Donaldson, make him feel bad. But he and other farmers have learned to live with it as part and parcel of being a farmer.

According to the charity Feeding America, more than 6 billion pounds of fruits and vegetables go unharvested or unsold each year.

Itís because much of the food on a farm falls victim to aesthetic trifles: the misshapen peach, the tomato too large to fit in a three-pack. Or in an uncertain economy, a farmer grows more than he market demands, then leaves entire fields and orchards unharvested.

We are growing more food than we know what to do with.

And this early-stage waste is only the beginning.

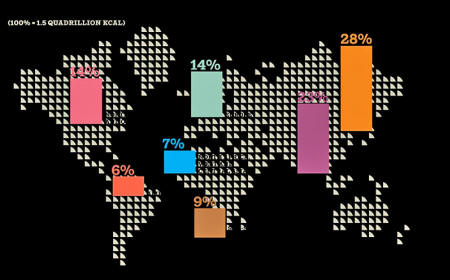

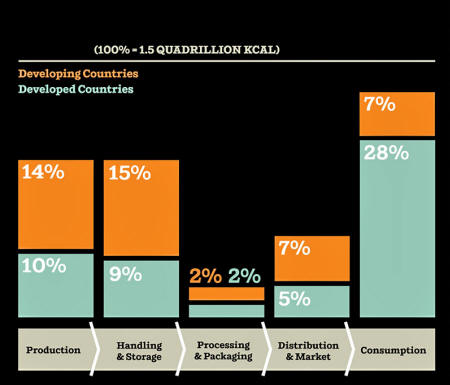

From transport to processor to retailer to consumer, food waste affects every step of the supply chain between farm and fork. In developing countries, nearly 50 percent of the loss happens early in foodsí life: inefficient harvesting, spoilage, inadequate processing, obsolete transport technologies and other systemic problems.

In Western nations, the problems are heavily weighted toward consumer and retail waste.

A comprehensive 2012 report by the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) found that a whopping 43 billion pounds of food in the U.S. was thrown away just on the retail level in 2008.

Reducing food losses by only 15 percent would be enough food to feed more than 25 million Americans each year.

But supermarket food is marketed with an eye toward bulk, convincing shoppers to take home more than they can use.

"There is a terrible push to make consumers buy more than they need, through family-sized packaging and buy-one-get-one-free promotions," says Tim Fox, co-author of "Global Food - Waste Not, Want Not" a report from the Institution of Mechanical Engineers (IMechE).

Still, all this pre-consumed food waste doesnít let consumers off the hook.

Think of your own fridge right now - the unappealing leftovers, the wilted lettuce, the expired milk and yogurt. A quarter of those items, according to the NRDC, will ultimately end up in the trash.

So, why worry about this?

With nearly a billion hungry people in the world, 50 million in the U.S., the moral dimension is clear. Except that conservation doesnít go straight from A to B: Your half-eaten sandwich is not going to make it to people who need it. We need to worry because in a global commodity market, waste drives food prices up, for everyone.

The United Nationís Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) is currently working on a comprehensive report, scheduled to be out in October, that shows the link between how global food prices are set and the many tons of food we throw away.

They know this much already:

The amount of annual consumer food waste in industrialized nations is equal to an entire yearís food production in sub-Saharan Africa.

FOOD WASTE, AMERICAN-STYLE

Spoiled milk, old fruit, unwanted pasta: It adds up.

Pictured is the amount (and type) of food wasted monthly by the average American household, as measured by researchers at the University of Arizona in 2004. Astonishingly, the study found that 14% of the trash was edible goods whose owners had not even bothered to take out of its packaging. Overall, 14% of all food brought into the average household annually gets tossed - 12% of all meat, 26% veggies, 24% fruit.

The environmental toll for throwing away so much uneaten food is also costly.

Of the millions of tons that we waste in America each year, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates 96 percent ends up in landfills. And currently, food waste is the number one material taking up landfill space, more than paper or plastic.

This produces methane gas, one of the most harmful atmospheric pollutants. Itís true that some food waste is inevitable. There will always be a percentage of food grown that is not consumed.

But there are also many ways to prevent unnecessary loss.

We can do this!

The Path Forward - Data

Andrew Shakman co-founded LeanPath almost a decade ago after discovering a shocking piece of information: Most restaurants and large commercial food operations had no clue how much and what kind of food they were throwing away.

Even when knowing would save them money.

"Food has been perceived as more affordable than labor," says Shakman, "and the lower the cost, the less people were concerned about protecting it."

The Portland, Oregon-based company is one of many using data to help change the worldís waste habits.

As Dana Gunders, author of the 2012 NRDC food waste study, notes, itís because of the paucity of good numbers on the topic that,

"food waste has not been on peopleís radars."

WHERE WE WASTE - PRODUCTION

In developing nations, this stage sees vast amounts of wastage, often because processing facilities are lacking or nonexistent.

Without, say, an adequate facility for drying rice or bottling milk, farm products may spoil before they ever make it to consumers. A study by the European Commission estimates that nearly 40% of total food loss (excluding farm-level loss), happens during manufacturing.

Shakmanís system works like this:

A worker weighs food about to be thrown out on a small scale and selects from labeled buttons to indicate what is being tossed. In real time, food companies are able to tabulate how and what is being wasted - without using too much employee time.

Shakman is shy to give out exact numbers of what his clients are wasting but he says that his 150 or so customers (which include University of California at Berkeley dining halls and the MGM Grand Buffet in Las Vegas) have seen waste plummet by up to 80 percent after installing the system, as well as big cost savings.

"Data drives behavioral change," Shakman says.

Anecdotal evidence from farmers confirms this. When Donaldson started tracking the waste created on his farm, he was shocked by some of the results.

For instance, 20 percent of his strawberries were being left to rot in the field.

"That used to be a loss we could withstand," he says. "But a farmerís profit margins have gotten tighter and tighter and a 20 percent loss has become unaffordable."

Once Donaldson saw the data, he instantly became proactive, putting his overripe or blemished berries into jams and jellies that he packages for sale.

Faced with similar losses on garlic and tomatoes, he started producing a line of tomato sauce. Bruised peaches and peppers go into a line of peach salsa. Now the items Donaldson was tracking as a net loss have been converted to a gain.

But how do you change the behavior of supermarkets, which still believe that the appearance of abundance outweighs lost revenue?

Data can even help mitigate that loss. A combined task force of the National Restaurant Association, the Grocery Manufacturers Association and the Food Marketing Institute just released its first-ever self-generated report on food waste.

Laura Abshire, sustainability director for the National Restaurant Association, notes that the knowledge that the retail sector produces over 4 billion pounds of food waste annually incites a call for action.

"As our members learn the cost of wasting, they are changing their practices," she says.

The Path Forward - Technology

Refrigerators that tell you when your food is going bad.

Giant vats of organic waste using the same process as the human stomach to make energy. Mobile apps that help you shop more efficiently. As more people become aware of food waste as a problem, technology makers are busy coming up with solutions.

For example, thereís a host of apps that help shoppers plan meals better to avoid overbuying perishable items, or calculate the shelf life of different groceries. In the home, smart fridges now give consumers even more information about their food.

These fridges, pioneered by LG and Samsung, help keep track of your perishables, alert you when something is about to spoil and use Internet connectivity to help devise recipes.

At this point, you still have to input all the items you buy; the next-generation smart fridge promises to automatically scan its own contents.

WHERE WE WASTE - IN STORES

The price of food has a lot to do with who wastes.

In Western nations food is historically cheap, and food operations have little incentive to conserve. One U.S. study from the University of Arizona found that, in retail, convenience stores had the highest levels of waste (26.3% of the total) - mostly cheap cooked food that often goes into the trash.

Abroad and in the U.S., waste operators and big food retailers have been using anaerobic digesters, giant sealed containers where bacteria breaks food waste down into biogas, a renewable energy source that comes from organic material fermenting without oxygen, to make energy from compostable food.

In South Central Los Angeles this past year, the supermarket chain Kroger built a new digester that serves 369 Southern California stores:

Annually it will create 13 million kilowatt hours, or enough to power 2,000 homes for a year while saving 150 tons of food a day that would normally be hauled to landfills.

The company that invented this behemoth, Boston-based Feed Resource Recovery, was started by a pair of business school graduates in 2007.

"The hardest thing," according to co-founder Nick Whitman, was figuring out how to make this "closed loop" system of waste management economically attractive to clients.

As it turns out, not having to haul garbage to landfills is actually a huge cost-saver.

"It has a significant upside of saving millions in waste-removal costs," Whitman says, speaking of the Kroger plant.

His company now has a number of other projects in the pipeline, not all of them for supermarkets.

Of course, the ideal situation is for food to be digested by humans, not anaerobics.

Studies show that most restaurants and supermarkets still are not getting the majority of their edible food waste to food banks or other organizations before it spoils.

The Path Forward - Propaganda

If all goes well, by the end of the year, the eight pigs tucked away in a corner of Stepney City Farm in East London will be the most famous porcine beasts in all of England.

As part of "The Pig Idea," a 2013 campaign against the 2002 European ban on the feeding of catering waste to pigs, food waste activist Tristram Stuartís organization Feeding the 5000 is partnering with the Mexican restaurant chain Wahaca to rear the hogs entirely on legally permissible food waste.

Campaign coordinator Edd Colbert says that after seven months, the pigs will be "turned into pork" and fed to 5,000 people in Londonís Trafalgar Square in a huge feast.

"They donít seem too hungry," Colbert says with disappointment as we enter the pen, explaining apologetically that Modern Farmer has arrived on the heels of a radio team.

"Everyone wants to see them eating," he says of the barrage of journalists that has come to view the pigs.

This public campaign, complete with cool logos and social media blasts, is one of dozens launched in the U.K. over the past few years.

The island nation was one of the biggest per-capita food wasters on the planet, but thanks to over a decade of sustained governmental, business and nonprofit research and programming, itís becoming a global leader on the issue.

Englandís magic trick? Applying savvy public relations to the subject.

The countryís interest in food waste has its roots in a 1999 European Union initiative to severely cap landfills.

In response, the government helped found public-private partnership WRAP, which has found great success in putting out headline-grabbing research about how much food is wasted as well as engineering public awareness projects.

"Theyíve basically done a huge amount of campaigning work," says Dr. David Evans, sociologist at the University of Manchester, who recently completed a nine-month ethnography of how food gets wasted in households in Manchester.

"So itís not activism in the sense of dumpster-diving or marginal activity or social movements; theyíve really kind of pushed the issue up the agenda."

The public support of WRAP extends to the business community.

The Courtauld Commitment, a government-funded U.K. initiative in conjunction with over 50 grocery retailers and food manufacturers, kicked off in 2005.

Companies including Coca-Cola, Kelloggís, Nestlť, Heinz and Asda (part of Walmart Corporation) pledged to voluntarily cut down on their food and food packaging waste. Results have already been impressive, with an 8.8 percent reduction in supply chain waste (well higher than the 5 percent target).

Perhaps more important, reducing food waste in the U.K. has become, well, cool.

Now, meals prepared from dumpster-diving have a certain glamour unimaginable in the States, where there is a stigma attached to this kind of activity. Stuart, a handsome poster boy for the movement, has made public dinners from would-be garbage a global phenomenon after years of events in England.

His organization, along with help from other nonprofits, recently took its act to Amsterdam, where the "Damn Food Waste" lunch fed thousands in a public square in late June.

It recently did an event in New York City.

WHERE WE WASTE - ON THE FARM

See these lovely vegetables? Totally ripe, tasty... and unlikely to reach your plate.

Produce with aesthetic abnormalities is regularly culled from farms, as food retailers have stringent rules about what they sell. The NRDC estimates that 20% of fruits and vegetables are lost on the farm, but only 2% of grains and 3% of meat. Other factors, like bad weather, also contribute to crop loss.

Why do the British public relations programs work? Probably because the British focus on solutions rather than judgments.

"I think itís one of the few areas where I think the activists arenít particularly moralistic. They are very pragmatic, and frankly I find it hugely refreshing," says Evans.

The movement is spreading.

Even China, a country not known for conservationism or Earth-friendly policies, has begun public programs aimed at reducing waste.

The "Clean Your Plate" campaign, started earlier this year by young activists, and "Operation Empty Plate," started in April of last year, have made great strides in convincing young people that a clear plate is a cool plate.

China also has a president who has taken an unusually strong stance against food waste. Itís early for any solid stats on how much these efforts have reduced Chinaís waste, but the Chinese government is already reporting a reduction in wasteful banquets and unneeded luxury food purchases.

But back to those 9 billion people. Can wasting less food really solve the problem? The data suggests it could greatly help.

The World Resources Institute released a paper in June 2013 estimating that if food waste is cut in half - from 24 percent to 12 percent globally - that saving would also cut the number of additional calories needed by 2050 by 22 percent.

In other words, by just not wasting edible food, we could get about a quarter of the way to feeding the projected population.

Like recycling, itís going to take a coalition of governments, private companies, nonprofit organizations and committed researchers to change our bad habits and inefficient processes, but thereís no time to lose.

Letís stop throwing our future away.