|

from

TheVerge Website

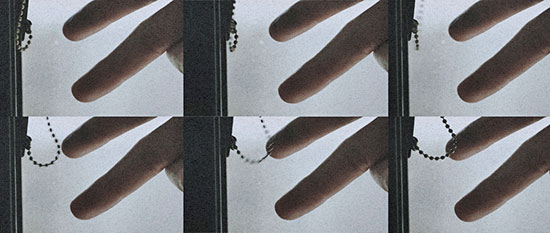

His left arm was stretched out on the operating table, his sleeve rolled up past the elbow, revealing his first tattoo, the Air Force insignia he got at age 18, a few weeks after graduating from high school.

Sarver was trying a technique he learned in the military to block out the pain, since it was illegal to administer anesthetic for his procedure.

Tim, the proprietor of Hot Rod Piercing in downtown Pittsburgh, put down the scalpel and picked up an instrument called an elevator, which he used to separate the flesh inside in Sarver's finger, creating a small empty pocket of space.

Then, with practiced hands, he slid a tiny rare earth metal inside the open wound, the width of a pencil eraser and thinner than a dime.

When he tried to remove his tool, however, the metal disc stuck to the tweezers.

The implant stayed put the second time.

Tim quickly stitched the cut shut, and cleaned off the blood.

Tim dangled the needle from a string of suture next to Sarver's finger, closer and closer, until suddenly, it jumped through the air and stuck to his flesh, attracted by the magnetic pull of the mineral implant.

Tim started prepping a new tray of clean surgical tools. Now it was my turn.

Wearable technologies like Google's Project Glass are narrowing the boundary between us and our devices even further by attaching a computer to a person's face and integrating the software directly into a user's field of vision.

The paradigm shift is reflected in the

names of our dominant operating systems. Gone are Microsoft's

Windows into the digital world, replaced by a union of man and

machine: the iPhone or Android.

I first met Sarver at the home of his best friend, Tim Cannon, in Oakdale, a Pennsylvania suburb about 30 minutes from Pittsburgh where Cannon, a software developer, lives with his longtime girlfriend and their three dogs.

The two-story house sits next to a beer dispensary and an abandoned motel, a reminder the city's best days are far behind it. In the last two decades, Pittsburgh has been gutted of its population, which plummeted from a high of more than 700,000 in the 1980s to less than 350,000 today.

For its future, the city has pinned much of its hopes on the biomedical and robotics research being done at local universities like Carnegie Mellon.

Cannon led me down into the basement, which he and Sarver have converted into a laboratory. A long work space was covered with Arduino motherboards, soldering irons, and electrodes.

Cannon had recently captured a garter snake, which eyed us from inside a plastic jar.

The pair call themselves grinders - homebrew biohackers obsessed with the idea of human enhancement - who are looking for new ways to put machines into their bodies.

They are joined by hundreds of aspiring biohackers who populate the movement's online forums and a growing number, now several dozen, who have gotten the magnetic implants in real life.

Cannon looks and moves a bit like Shaggy from Scooby Doo, a languid rubberband of a man in baggy clothes and a newsboy cap. Sarver, by contrast, stands ramrod-straight, wearing a dapper three-piece suit and waxed mustache, a dandy steampunk with a high-pitched laugh.

There is a distinct division of labor between the two:

The moniker for their working unit is

Grindhouse Wetwares. Computers are hardware. Apps are software.

Humans are wetware.

Cannon got his own neodymium magnetic implant a year before Sarver.

Putting these rare earth metals into the body was pioneered by artists on the bleeding edge of piercing culture and transhumanists interested in experimenting with a sixth sense.

Steve Haworth, who specializes in the bleeding edge of body modification and considers himself a "human evolution artist," is considered one of the originators, and helped to inspire a generation of practitioners to perform magnetic implants, including the owner of Hot Rod Piercing in Pittsburgh.

(Using surgical tools like a scalpel is a grey area for piercers. Operating with these instruments, or any kind of anesthesia, could be classified as practicing medicine. Without a medical license, a piercer who does this is technically committing assault on the person getting the implant.)

On its own, the implant allows a person to feel electromagnetic fields:

While this added perception is interesting, it has little utility.

But the magnet, explains Cannon, is more of a stepping stone toward bigger things.

As an example of how that might work, Cannon showed me a small device he and Sarver created called the Bottlenose.

It's a rectangle of black metal about half the size of a pack of cigarettes that slips over your finger. Named after the echolocation used by dolphins, it sends out an electromagnetic pulse and measures the time it takes to bounce back.

Cannon slips it over his finger and closes his eyes.

He twirls around the half-empty basement, eyes closed, then stops, pointing directly at my chest.

The way Cannon sees it, biohacking is all around us.

He took a pair of electrodes off the workbench and attached them to my temples.

A sharp pinch ran across my forehead as the first volts flowed into my skull.

He and Sarver laughed as my face involuntarily twitched.

History.01

In one sense, Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, part man, part machine, animated by electricity and with superhuman abilities, might be the first dark, early vision of what humans' bodies would become when modern science was brought to bear.

A more utopian version was put forward in 1960, a year before man first travelled into space, by the scientist and inventor Manfred Clynes.

Clynes was considering the problem of how mankind would survive in our new lives as outer space dwellers, and concluded that only by augmenting our physiology with drugs and machines could we thrive in extraterrestrial environs.

It was Clynes and his co-author Nathan Kline, writing on this subject, who coined the term cyborg.

At its simplest, a cyborg is a being with both biological and artificial parts: metal, electrical, mechanical, or robotic. The construct is familiar to almost everyone through popular culture, perhaps most spectacularly in the recent Iron Man films.

Tony Stark is surely our greatest contemporary cyborg:

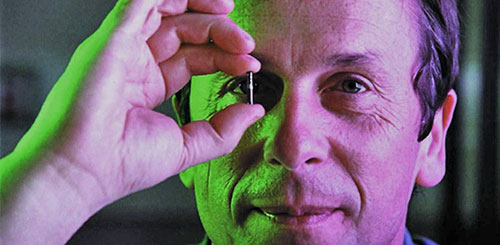

Britain is the birthplace of 21st-century biohacking, and the movement's two foundational figures present a similar Jekyll and Hyde duality.

One is Lepht Anonym, a DIY punk who was one of the earliest, and certainly the most dramatic, to throw caution to the wind and implant metal and machines into her flesh.

The other is Kevin Warwick, an academic at the University of Reading's department of cybernetics. Warwick relies on a trained staff of medical technicians when doing his implants.

Lepht has been known to say that all she requires is a potato peeler and a bottle of vodka.

In an article on h+, Anonym wrote:

Anonym's essay, a series of YouTube videos, and a short profile in Wired established her as the face of the budding biohacking movement.

It was Anonym who proved, with herself as the guinea pig, that it was possible to implant RFID chips and powerful magnets into one's body, without the backing of an academic institution or help from a team of doctors.

Over the last decade grinders have begun to form a loose culture, connected mostly by online forums like biohack.me, where hundreds of aspiring cyborgs congregate to swap tips about the best bio-resistant coatings to prevent the body from rejecting magnetic implants and how to get illegal anesthetics shipped from Canada to the United States.

There is another strain of biohacking which focuses on the possibilities for DIY genetics, but their work is far more theoretical than the hands-on experiments performed by grinders.

But while Anonym's renegade approach to bettering her own flesh birthed a new generation of grinders, it seems to have had some serious long-term consequences for her own health.

***

Part.02

I had Lepht Anonym in the back of my mind as I stretched my arm out on the operating table at Hot Rod Piercing.

The fingertip is an excellent place for a magnet because it is full of sensitive nerve tissue, fertile ground for your nascent sixth sense to pick up on the electro-magnetic fields all around us. It is also an exceptionally painful spot to have sliced open with a scalpel, especially when no painkillers are available.

The experience ranked alongside breaking my arm and having my appendix removed, a level of pain that opens your mind to parts of your body which before you were not conscious of.

For the first few days after the surgery, it was difficult to separate out my newly implanted sense from the bits of pain and sensation created by the trauma of having the magnet jammed in my finger. Certain things were clear:

They lurked like landmines in everyday objects - my earbuds, my messenger bag - sending my finger ringing with a deep, sort of probing force field that shifted around in my flesh.

High-tension wires seemed to give off a sort of pulsating current, but it was often hard to tell, since my finger often began throbbing for no reason, as it healed from the trauma of surgery.

Playing with strong, stand-alone magnets was a game of chicken.

The party trick of making one leap across a table towards my finger was thrilling, but the awful squirming it caused inside my flesh made me regret it hours later. Grasping a colleague's stylus too near the magnetic tip put a sort of freezing probe into my finger that I thought about for days afterwards.

Within a few weeks, the sensation began to fade. I noticed fewer and fewer instances of a sixth sense, beyond other magnets, which were quite obvious.

I was glad that the implant didn't interfere with my life, or prevent me from exercising, but I also grew a bit disenchanted, after all the hype and excitement the grinders I interviewed had shared about their newfound way of interacting with the world.

He was one of the first to experiment with implants, putting an RFID chip into his body back in 1998, and has also taken the techniques the farthest. In 2002, Prof. Warwick had cybernetic sensors implanted into the nerves of his arm.

Unlike the grinders in Pittsburgh, he had the benefits of anesthesia and a full medical team, but he was still putting himself at great risk, as there was no research on the long-term effects of having these devices grafted onto his nervous system.

I chatted with Warwick from his office at The University of Reading, stacked floor to ceiling with books and papers.

He has light brown hair that falls over his forehead and an easy laugh. With his long sleeve shirt on, you would never know that his arm is full of complex machinery. The unit allows Warwick to manipulate a robot hand, a mirror of his own fingers and flesh. What's more, the impulse could flow both ways.

Warwick's wife, Irena, had a simpler cybernetic implant done on herself.

When someone grasped her hand,

Prof. Warwick was able to experience the same sensation in

his hand, from across the Atlantic. It was, Warwick writes,

a sort of cybernetic telepathy, or empathy, in which his

nerves were made to feel what she felt, via bits of data

travelling over the internet.

But Prof. Warwick says that misses the point.

It's a sentiment that can take some getting used to.

With the advent of smartphones, says Prof. Warwick, all that has changed.

While he is an accomplished academic, Prof. Warwick has embraced biohackers and grinders as fellow travelers on the road to exploring our cybernetic future.

To that end, Prof. Warwick and one of his PhD students, Ian Harrison, are beginning a series of studies on biohackers with magnetic implants.

The end goal for Prof. Warwick, as it was for the team at Grindhouse Wetwares in Pittsburgh, is still the stuff of science fiction.

For Warwick, this will advance not just the human body and the field of cybernetics, but allow for a more practical evaluation the entire canon of Western thought.

It would be another attempt to study the mind, from inside and out, as Wittgenstein proposed.

But with access to objective data.

As the limits of space exploration become increasingly clear, a generation of scientists who might once have turned to the stars are seeking to expand humanity's horizons much closer to home.

On a hot day in mid-July, I went for a walk around Manhattan with Dann Berg, who had a magnet implanted in his pinky three years earlier.

I told him I was a little disappointed how rarely I noticed anything with my implant.

Berg worked for a while in the piercing and tattoo studio, which brought him into contact with the body modification community who were experimenting with implants.

At the same time, he was teaching himself to code and finding work as a front-end developer building web sites.

Berg took me to an intersection at Broadway and Bleecker. In the middle of the crosswalk, he stopped, and began moving his hand over a metal grate.

People passing by gave us odd stares as Berg and I stood next to each other in the street, waving our hands around inside an invisible field, like mystics groping blindly for a ghost.

Part.03

Cannon popped a tray of mashed potatoes in the microwave and showed me where he put his finger to feel the electromagnetic waves streaming off. We stepped out onto the back porch and let his three little puggles run wild.

The sound of cars passing on the nearby highway and the crickets warming up for sunset relaxed everyone.

I asked what they thought the potential was for biohacking to become part of the mainstream.

Brain implants are now being used to treat Parkinson's disease and depression. Scientists hope that brain implants might soon restore mobility to paralyzed limbs.

The crucial difference is that grinders are pursuing this technology for human enhancement, without any medical need.

Sarver joined the Air Force just weeks after 9/11.

In place of college, he got an education in electronics repairing fighter jets and attack helicopters.

He left the war a very different man.

Yet, while he rejected the conflict in the Middle East, Sarver's time in the military gave him a new perspective on the human body.

The boys from Grindhouse Wetwares both sucked down Parliament menthols the whole time we talked.

There was no irony for them in dreaming of the possibilities for one's body and willfully destroying it.

Flesh and blood are easily shed in grinder circles, at least theoretically speaking.

As far as the biohackers are

concerned, we are the best argument against

intelligent

design.

But technology marches on.

We came back into the kitchen for dinner.

As I wolfed down steak and potatoes, Cannon broke into a nervous grin.

He disappeared down into the basement lab and returned with a small device the size of a cigarette lighter, a simple circuit board with a display attached.

This was the HELEDD, the next step in the Grindhouse Wetwares plan to unite man and machine.

The smartphone in your pocket would act as the brain for this implant, communicating via bluetooth with the HELEDD, which would use a series of LED lights to display the time, a text message, or the user's heart rate.

Cannon hopes to have the operation in the next few months.

A big part of what drives the duo to move so fast is the idea that there is no hierarchy established in this space.

I point out that Steve Jobs may have died in large part because he was reluctant to get surgery, afraid that if doctors opened him up, they might not be able to put him back together good as new.

|