|

by John Noble Wilford

from

NewAgePointToInfinity Website

Two ancient skulls, one from central Africa and the other from the

Black Sea republic of Georgia, have shaken the human family tree to

its roots, sending scientists scrambling to see if their favorite

theories are among the fallen fruit.

Probably so, according to paleontologists, who may have to make

major revisions in the human genealogy and rethink some of their

ideas about the first migrations out of Africa by human relatives.

|

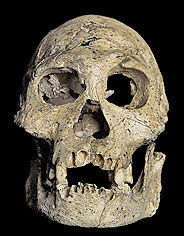

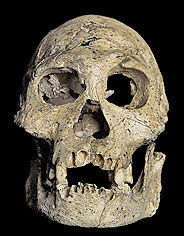

National Geographic Society

This could be the face of the first human to leave Africa, the

August issue of National Geographic magazine says. The

1.75-million-year-old skull, found in the republic of Georgia, had a

tiny brain, not nearly the size scientists thought our ancestors

needed to migrate into a new land. |

Yet, despite all the confusion and uncertainty the skulls have

caused, scientists speak in superlatives of their potential for

revealing crucial insights in the evidence-disadvantaged field of

human evolution.

The African skull dates from nearly 7 million years ago, close to

the fateful moment when the human and chimpanzee lineages went their

separate ways. The 1.75-million-year-old Georgian skull could answer

questions about the first human ancestors to leave Africa, and why

they ventured forth.

Still, it was a shock, something of a one-two punch, for two such

momentous discoveries to be reported independently in a single week,

as happened in July.

"I can't think of another month in the history of paleontology in

which two such finds of importance were published," said Dr. Bernard

Wood, a paleontologist at George Washington University. "This really

exposes how little we know of human evolution and the origin of our

own genus Homo."

Every decade or two, a fossil discovery upsets conventional wisdom.

One more possible "missing link" emerges. An even older member of

the hominid group, those human ancestors and their close relatives

(but not apes), comes to light. Some fossils also show up with

attributes so puzzling that scientists cannot decide where they

belong, if at all, in the human lineage.

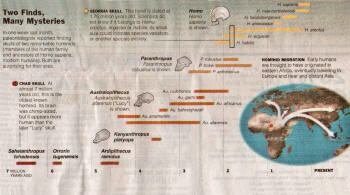

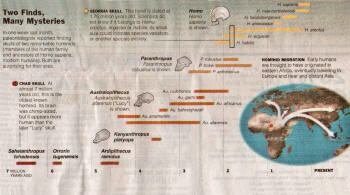

At each turn, the family tree, once drawn straight as a ponderosa

pine, has had to be reconfigured with more branches leading here and

there and, in some cases, apparently nowhere.

"When I went to medical school in 1963, human evolution looked like

a ladder," Dr. Wood said. The ladder, he explained, stepped from

monkey to modern human through a progression of intermediates, each

slightly less apelike than the previous one.

But the fact that modern Homo sapiens is the only hominid living

today is quite misleading, an exception to the rule dating only

since the demise of Neanderthals some 30,000 years ago.

Fossil

hunters keep finding multiple species of hominids that overlapped in

time, reflecting evolutionary diversity in response to new or

changed circumstances. Not all of them could be direct ancestors of

Homo sapiens. Some presumably were dead-end side branches.

So a tangled bush has now replaced a tree as the ascendant imagery

of human evolution. Most scientists studying the newfound African

skull think it lends strong support to hominid bushiness almost from

the beginning.

That is one of several reasons Dr. Daniel E. Lieberman, a biological

anthropologist at Harvard, called the African specimen "one of the

greatest paleontological discoveries of the past 100 years."

The skull was uncovered in the desert of Chad by a French-led team

under the direction of Dr. Michel Brunet of the University of Poitiers. Struck by the skull's unusual mix of apelike and evolved

hominid features, the discoverers assigned it to an entirely new

genus and species — Sahelanthropus tchadensis. It is more commonly

called Toumai, meaning "hope of life" in the local language.

In announcing the discovery in the July 11 issue of the journal

Nature, Dr. Brunet's group said the fossils - a cranium, two lower

jaw fragments and several teeth - promised "to illuminate the

earliest chapter in human evolutionary history."

The age, face and geography of the new specimen were all surprises.

About a million years older than any previously recognized hominid,

Toumai lived close to the time that molecular biologists think was

the earliest period in which the human lineage diverged from the

chimpanzee branch. The next oldest hominid appears to be the

6-million-year-old Orrorin tugenensis, found two years ago in Kenya

but not yet fully accepted by many scientists.

After it is

Ardipithecus ramidus, which probably lived 4.4 million to 5.8

million years ago in Ethiopia.

"A lot of interesting things were happening earlier than we

previously knew," said Dr. Eric Delson, a paleontologist at the City

University of New York and the American Museum of Natural History.

The most puzzling aspect of the new skull is that it seems to belong

to two widely separated evolutionary periods.

Its size indicates

that Toumai had a brain comparable to that of a modern chimp, about

320 to 380 cubic centimeters.

Yet the face is short and relatively

flat, compared with the protruding faces of chimps and other early

hominids. Indeed, it is more humanlike than the "Lucy" species,

Australopithecus afarensis, which lived more than 3.2 million years

ago.

"A hominid of this age,"

Dr. Wood wrote in Nature, "should certainly

not have the face of a hominid less than one-third of its geological

age."

Scientists suggest several possible explanations.

Toumai could

somehow be an ancestor of modern humans, or of gorillas or chimps.

It could be a common ancestor of humans and chimps, before the

divergence.

"But why restrict yourself to thinking this fossil has to belong to

a lineage that leads to something modern?" Dr. Wood asked. "It's

perfectly possible this belongs to a branch that's neither chimp nor

human, but has become extinct."

Dr. Wood said the "lesson of history" is that fossil hunters are

more likely to find something unrelated directly to living creatures

— more side branches to tangle the evolutionary bush. So the picture

of human genealogy gets more complex, not simpler.

A few scientists sound cautionary notes. Dr. Delson questioned

whether the Toumai face was complete enough to justify

interpretations of more highly evolved characteristics. One critic

argued that the skull belonged to a gorilla, but that is disputed by

scientists who have examined it.

Just as important perhaps is the fact that the Chad skull was found

off the beaten path of hominid research. Until now, nearly every

early hominid fossil has come from eastern Africa, mainly Ethiopia,

Kenya and Tanzania, or from southern Africa.

Finding something very

old and different in central Africa should expand the hunt.

"In hindsight, we should have expected this,"

Dr. Lieberman said.

"Africa is big and we weren't looking at all of Africa. This fossil

is a wake-up call. It reminds us that we're missing large portions

of the fossil record."

Although overshadowed by the news of Toumai, the well-preserved

1.75-million-year-old skull from Georgia was also full of surprises,

in this case concerning a later chapter in the hominid story.

It

raised questions about the identity of the first hominids to be

intercontinental travelers, who set in motion the migrations that

would eventually lead to human occupation of the entire planet.

The discovery, reported in the July 5 issue of the journal Science,

was made at the medieval town Dmanisi, 50 miles southwest of

Tbilisi, the Georgian capital. Two years ago, scientists announced

finding two other skulls at the same site, but the new one appears

to be intriguingly different and a challenge to prevailing views.

Scientists have long been thought that the first hominid

out-of-Africa migrants were Homo erectus, a species with large

brains and a stature approaching human dimensions. The species was

widely assumed to have stepped out in the world once they evolved

their greater intelligence and longer legs and invented more

advanced stone tools.

The first two Dmanisi skulls confirmed one part of the hypothesis.

They bore a striking resemblance to the African version of H.

erectus, sometimes called Homo ergaster. Their discovery was hailed

as the most ancient undisputed hominid fossils outside Africa.

But the skulls were associated with more than 1,000 crudely chipped

cobbles, simple choppers and scrapers, not the more finely shaped

and versatile tools that would be introduced by H. erectus more than

100,000 years later. That undercut the accepted evolutionary

explanation for the migrations.

The issue has become even more muddled with the discovery of the

third skull by international paleontologists led by Dr. David

Lordkipanidze of the Georgian State Museum in Tbilisi. It is about

the same age and bears an overall resemblance to the other two

skulls. But it is much smaller.

"These hominids are more primitive than we thought,"

Dr. Lordkipanidze said in an article in the current issue of National

Geographic magazine. "We have a new puzzle."

To the discoverers, the skull has the canine teeth and face of

Homo habilis, a small hominid with long apelike arms that evolved in

Africa before H. erectus. And the size of its cranium suggests a

substantially smaller brain than expected for H. erectus.

In their journal report, the discovery team estimated the cranial

capacity of the new skull to be about 600 cubic centimeters,

compared with about 780 and 650 c.c.'s for the other Dmanisis

specimens. That is "near the mean" for H. habilis, they noted.

Modern human braincases are about 1,400 cubic centimeters.

Dr. G. Philip Rightmire, a paleontologist at the State University of

New York at Binghamton and a member of the discovery team, said that

if the new skull had been found before the other two, it might have

been identified as H. habilis.

Dr. Ian Tattersall, a specialist in human evolution at the natural

history museum in New York City, said the specimen was "the first

truly African-looking thing to come from outside Africa." More than

anything else, he said, it resembles a 1.9-million-year-old Homo

habilis skull from Kenya.

For the time being, however, the fossil is tentatively labeled Homo

erectus, though it stretches the definition of that species.

Scientists are pondering what lessons they can learn from it about

the diversity of physical attributes within a single species.

Dr. Fred Smith, a paleontologist who has just become dean of arts

and sciences at Loyola University in Chicago, agreed that his was a

sensible approach, at least until more fossils turn up. Like other

scientists, he doubted that two separate hominid species would have

occupied the same habitat at roughly the same time. Marked

variations within a species are not uncommon; brain size varies

within living humans by abut 15 percent.

"The possibility of variations within a species should never be

excluded," Dr. Smith said. "There's a tendency now for everybody to

see three bumps on a fossil instead of two and immediately declare

that to be another species."

Some discoverers of the Dmanisi skull speculated that these hominids

might be descended from ancestors like H. habilis that had already

left Africa. In that case, it could be argued that H. erectus itself

evolved not in Africa but elsewhere from an ex-African species.

If

so, the early Homo genealogy would have to be drastically revised.

click image to

enlarge

But it takes more than two or even three specimens to reach firm

conclusions about the range of variations within a species. Still,

Georgia is a good place to start.

The three specimens found there

represent the largest collection of individuals from any single site

older than around 800,000 years.

"We have now a very rich collection, of three skulls and three

jawbones, which gives us a chance to study very properly this

question" of how to classify early hominids, Dr. Lordkipanidze said,

and paleontologists are busy this summer looking for more skulls at

Dmanisi.

"We badly want to know what the functional abilities of the first

out-of-Africa migrants were," said Dr. Wood of George Washington

University. "What could that animal do that animals that preceded it

couldn't? What was the role of culture in this migration? Maybe

other animals were leaving and the hominids simply followed."

All scholars of human prehistory eagerly await the next finds from

Dmanisi, and in Chad. Perhaps they will help untangle some of the

bushy branches of the human family tree to reveal the true ancestry

of Homo sapiens.

|