|

February 28, 2012

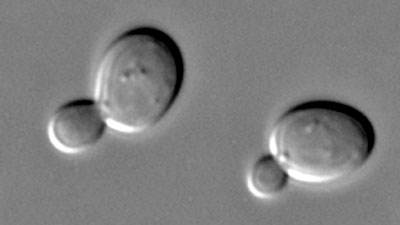

Wikimedia Commons,

Masur

Yeast cells aren’t normally magnetic, but a little genetic engineering can make them thralls to a magnetic field.

The research, published today (February 28) in PLoS Biology, suggests that manipulations of a few widely expressed genes could be enough to get any cell magnetized, which could be a powerful tool for both research and medicine.

Xiaoping Hu,

who did not

participate in the study, added that this work appears to be the

first attempt to magnetize yeast, and may “give guidance” to others

working to induce magnetism in eukaryotic cells.

Yeast usually shunt excess iron into

vacuoles, where it’s kept in a non-magnetic state, explained

synthetic biologist Pamela Silver, whose postdoc Keiji

Nishida performed the work.

Magnetism is an under-exploited

property, and Nishida hoped that working out the underlying pathways

of cell magnetism in yeast could be a stepping stone to making any

cell into a magnet.

Nishida then added a gene for human ferritin, an iron storage protein.

Ablating the yeast’s iron detox pathway and juicing its iron storage was enough to induce mild magnetism in yeast grown in a solution containing the iron-based compound ferric citrate:

Nishida and Silver also hoped to understand what, if any, ordinary pathways in yeast could contribute to magnetism.

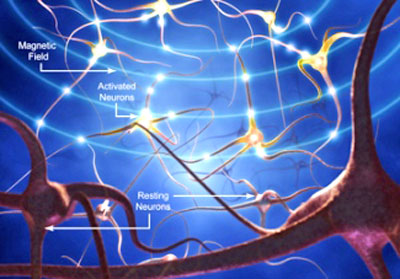

After screening knockouts for changes in magnetic properties, they identified Tco89p, a non-essential component of TORC1 (target of rapamycin complex 1), which regulates cell growth in response to environmental changes like alterations in redox state, stress, and nutrients.

Cells missing Tco89p showed reductions in magnetism, while transfecting yeast cells with plasmids containing multiple copies of TCO89 were more magnetic. Tco89 appears to be working by altering the redox state of the yeast cells, but the details of those alterations remain unclear.

Working out the mechanism of the induced yeast magnetism could provide synthetic biologists with a new tool.

Magnetism also has other basic research applications, including producing bio-compatible magnetic nanoparticles, which are studied as possible drug delivery systems, Hu said.

Magnetism may also serve as a new

technique for separating cells of a population. Indeed, Nishida

showed that the magnetic yeast can be trapped in a magnetic column.

This technique could also theoretically be a step in an anticancer therapy: applying alternating current magnetic fields to cells containing magnetic particles transfers magnetic energy in the form of heat, selectively killing just the particle-containing cells.

Magnetic Fields Effect on Humans from prd34.blogspot Website

They then enhanced the magnetic sensitivity even further through interaction with a second protein that regulates cell metabolism.

Since the same metabolic protein

functions similarly in cells ranging from simple yeast to more

advanced - human - cells, the new method could potentially be

applied to a much wider range of organisms.

Magnetic fields are everywhere, but few organisms can sense them.

Those that do, such as birds and

butterflies, use magnetic sensitivity as a kind of natural global

positioning system to guide them along migratory routes. How these

few magnetically aware organisms gain their magnetism remains one of

biology's unsolved mysteries.

Researchers Pamela Silver, Ph.D., and Keiji Nishida, Ph.D., were able to imbue yeast with similar properties.

|