|

|

|

from MotherJones Website

if Monsanto and Dow get their way.

During the late December media lull, the USDA didn't satisfy itself with green-lighting Monsanto's useless, PR-centric "drought-tolerant" corn.

It also prepped the way for approving a

product from Monsanto's rival Dow Agrosciences - one that

industrial-scale corn farmers will likely find all too useful.

The company's pitch to farmers is simple:

At risk of sounding overly dramatic, the product seems to me to bring mainstream US agriculture to a crossroads.

If Dow's new corn makes it past the USDA and into farm fields, it will mark the beginning of at least another decade of ramped-up chemical-intensive farming of a few chosen crops (corn, soy, cotton), beholden to a handful of large agrichemical firms working in cahoots to sell ever larger quantities of poisons, environment be damned.

If it and other new herbicide-tolerant

crops can somehow be stopped, farming in the US heartland can be

pushed toward a model based on biodiversity over monocropping,

farmer skill in place of brute chemicals, and healthy food instead

of industrial commodities.

The technology cut a huge chunk of work

out of farming, allowing farmers to cultivate ever more massive

swathes of land with less labor.

When Roundup Ready crops hit the market in the mid-1990s, farmers started applying more and more Roundup per acre. From Mortensen, at al, "Navigating a Critical Juncture for Sustainable Weed Management," BioScience, Jan. 2012

But by the time farmers had structured their operations around Roundup Ready and its promise of effortless weed control, the technology had begun to fail.

In what was surely one of the most predictable events in the history of agriculture, it turned out than when farmers douse millions of acres of land with a single herbicide year after year, weeds evolve to resist that poison.

Last summer, Roundup-resistant superweeds flourished in huge swathes of US farmland, forcing farmers to apply gushers of toxic herbicide cocktails and even resort to hand-weeding - not a fun thing to do on a huge farm.

A recent article in the industrial-ag

trade journal Delta Farm Press summed up the situation: "Days of

Easy Weed Control Are Over."

In its petition to the USDA to approve 2,4-D-resistant corn, the company explicitly pitched it as the answer to farmers' Roundup trouble. The 2,4-D trait will be "stacked" with Monsanto's Roundup trait to,

Note that the new product marks a point

of collusion, not competition, between industry titans Dow and

Monsanto - they plan to license the 2,4-D and Roundup traits to each

other to form "stacked" hybrids.

The USDA, for its part, is buying what Dow is selling.

Its Draft Environmental Assessment offers no critique of Dow's claims, and recommends that the product be deregulated. The agency is currently seeking public comment on the matter; the comment period ends February 27.

Doug Gurian-Sherman, a senior scientist with the Union of Concerned Scientists, told me that when the USDA brings a GMO product to the comment stage after having recommended deregulation, it "almost always" green-lights the product.

Dow's new GM corn merits just such a public uproar, it seems to me.

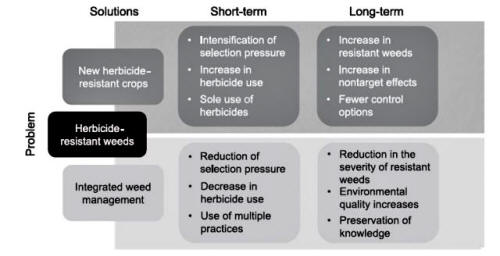

A just-released paper from a group of

researchers led by Pennsylvania State University crop scientist

David A. Mortensen makes a strong case that new

herbicide-tolerant crops will lead US agriculture down a path of

ever-increasing addiction to agrichemicals. (abstract

here.)

They retort that resistance to two or more herbicides isn't a rare occurrence at all:

They add that on millions of acres of farmland in the Midwest and South, many weeds will only need to develop a single resistance pathway, because they're already resistant to Roundup.

That is, when farmers apply 2,4-D at

will to weeds that are already resistant to Roundup, they'll

essentially be selecting for weeds that can resist both.

The authors predict that glyphosate (Roundup) use will hold steady at high levels - and use of other herbicides, like 2,4-D, will soar. From Mortensen, at al, "Navigating a Critical Juncture for Sustainable Weed Management," BioScience, Jan. 2012

All in all, the authors conclude, chances are "actually quite high" that Dow's new product will unleash a new generation of superweeds that resist both Roundup and 2,4-D.

If 2,4-D resistance does indeed emerge, farmers will likely

respond just as they responded to the advent of Roundup resistance -

by applying ever higher doses.

They say the compound is quite volatile and prone to be carried in air, where it can do damage to non-target plants like the neighbor's vegetable farm.

They also fear that if you're a farmer

determined not to use a stacked 2,4-D/Roundup seed, you could be

forced to if your neighbor's 2,4-D spray keeps knocking down your

corn.

However, as I've reported before, the advocacy group Beyond Pesticides points to both epidemiological and lab-based evidence linking it non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and other cancers.

It's also an endocrine disruptor, Beyond Pesticides reports, meaning it can,

And in 2004, a coalition of more than a dozen environmental and social justice groups, including the Natural Resources Defense Council and Pesticide Action Network, wrote a letter to the EPA rebuking it for underestimating the health risks of 2,4-D - in particular, its carcinogenicity.

The EPA, it goes without saying, brushed

those concerns aside.

IWM would mean bringing skill and thought back to farming, and it would push farmers into planting more crops than just corn and soy. The biggest obstacle to IWM over the Dow/Monsanto vision doesn't lie in efficiency or economics.

The authors cite research showing that,

Rather, the obstacle lies in political economy: the power of the agrichemical companies to set the research agenda both in public universities and at the USDA, and to use farm supports to reward farmers for growing a narrow set of crops.

Farmers have been using Roundup

technology for nearly a generation; they will grope for the next fix

to it until our public ag-research complex shows that them there's a

better, cheaper way.

We don't have to go that way. It's time

to raise hell.

Fork in the road. From Mortensen, at al, "Navigating a Critical Juncture for Sustainable Weed Management,"

BioScience, Jan. 2012

|