|

Chapter 3

- What Hawaii Tells Us About Evolution

Terence: The subject of this particular trialogue is Hawaii, what

this island tells us about evolution, and how it relates to island

ecosystems and their evolutionary process generally. The task falls

to me because as chance would have it, in the course of my life I

have visited most of the major theaters of evolution that involve

island groups considered to be exemplars of the various types of

island groups on the planet.

Hawaii, where we are recording this trialogue, is a group of

mid-ocean volcanic islands. The only other mid-ocean volcanic island

groups in the world are the Azores, the Canaries and the Seychelles.

They offer great contrast to Hawaii, particularly the Seychelles,

which as a portion of the Madagascar land mass has been above water

some 300 million years, perhaps longer than any other place on the

planet.

There the evolutionary process offers a dramatic contrast to

the far more recent evolution in the Hawaiian Islands. The Hawaiian

Islands represent the unique case, because of the size of the

volcanic calderas and of the vents beneath the Pacific floor that

have created them. In fact, these vents and volcanic conduits are

the largest on the planet.

What we have in Hawaii is a tectonic

plate sliding slowly toward southern Russia and Japan that is

crossing over a weak place in the Earth's crust, a place where the

core magma of the planet lies a considerable percentage closer to

the surface than anywhere else on earth. The result of this

situation is a series of islands formed in the same spot that each,

after its volcanic birth, is rafted away on the continental plate

towards the northwest.

The life in the Hawaiian islands shows 30 to 35 million years of

indemnification using the ordinary rates of gene change that

biologists recognize. Nevertheless, geologically speaking, no

Hawaiian island is over 12 million years old.

The obvious

interpretation of these facts is that life arose out here on islands

which no longer exist, and as islands rose and fell, the life hopscotched from one island to another. Indeed, the dispersal rate

of birds, tree snails, and other organisms moving eastward from

Kauai across Oahu, Molokai and Maui to the Big Island, Hawaii

itself, shows that this gradient is still operable.

The forests of

Hawaii are the most species-poor forests of the major islands.

Hawaii is species poor because animals are still arriving here from

the other islands. Nevertheless because these volcanoes are so huge,

Hawaii has a complete range of ecological systems, from sea level to

14,000 feet, virtually the entire range on the planet in which life

is able to locate itself.

The volcano itself, Mauna Loa, is by

volume the world's largest mountain, because is is already a 14,000

foot mountain when it breaks through to sea level, having risen from

the Pacific floor, and in this part of the world the Pacific Ocean

is 13,000 feet deep. This mountain was enormous before it ever broke

water. It now rises 13,000 feet above sea level, and its sister

mountain, Mauna Kea, is shorter by only 120 feet.

What has been created out here is a very closed ecosystem far from

any continental land mass. The forms of life which arise here arise

on rafted debris or tucked into the feathers of migratory birds or

in some other highly improbable fashion. What we see here is a

winnowing of continental species based on extreme improbability. As

an example, a very common Sierra Nevada wildflower of no great

distinction apparently arrived millions of years ago as a single

seed on Maui, and by that crossing has created a mutated race of

plants that we know as the Hawaiian Silversword, one of the most

bizarre endemic plants that the island has produced.

In terms of islands within islands and the fractal adumbration of

nature; it's very evident here. For example, because the island is

created by a series of lava flows of varying ages, there is a

constant process in which ecosystems become islanded by lava flows.

And so you have a series of micro-islands of species that develop

independently of each other even though they may only be some few

miles apart, but separated by a landscape so toxic and desolate that

there is very little intermixing of genes.

This is thought to have

been a formative factor in the evolution of the Hawaiian fruit-flies,

Drosophila, which of course were very useful in early studies of

genetics because the chromosomes of the Hawaiian Drosophila are ten

thousand times larger than the ordinary Drosophila and in the era

before electron microscopes you could actually color band these with

certain dyes.

Using chromosomes of these Hawaiian Drosophila, early

chromosome studies went forward.

In terms of extrapolating all of this particular natural history

data into some sort of general model, I think what life on the

island brings home to us is that the earth itself is an island. I've

been saying for many years that one of the most revolutionary yet

totally trivial and predictable revolutions sure to come in biology

is the recognition that models of island isolation or species

dispersion across oceans can easily be expanded to the

three-dimensional ocean of outer space.

Very clearly viruses, prions,

gene fragments, molecularly coded information, percolate between the

stars as a statistically very low component of the general cosmic

dust and debris. Indeed, there have been many attempts to establish

this idea, by Fred Hoyle and others. Recently a theory of the cometary origin of life has been put forward. It seems to me

perfectly obvious that in time these notions will be embraced; after

all, viruses can freeze down to crystalline states that are almost

minerals.

And as for a dispersion between celestial bodies, it's now

generally agreed that a number of meteorites that have been

recovered in the Antarctic are in fact fragments of Mars.* So the

work on island dispersal patterns and the statistical mechanics of

this process will eventually, I think, play a role in modeling how

life is dispersed throughout the galaxy.

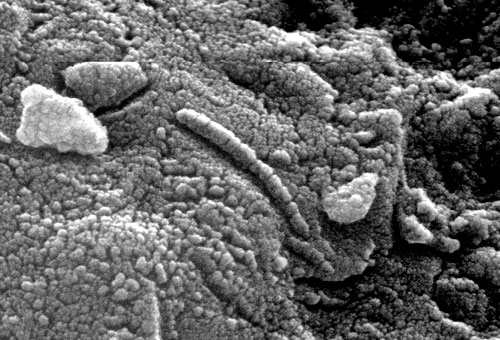

* This trialogue was recorded prior to the 1996 discovery of fossil

life in a meteor of Martian origin (click below image).

Some of the other

islands that I've been fortunate enough to relate to are the

Indonesian islands, which are the absolute other end of the

spectrum of the class of tropical islands. What we have here in

Hawaii, as I said, is mid-ocean islands far from continental

floras and faunas, while Indonesia is in fact a submerged

continent.

As recently as 120,000 years ago,

Indonesia, from Sumatra to New Guinea, was a single land mass

which paleobiologists refer to as

Sundaland. In the process of this shallow continent's subsidence,

the sea filled in the low spots, so that today there is a direct

correlation between species differentiation on any two Indonesian

islands and the depth of the sea between them. These correlations

have been shown over and over. One of the great conundrums of 19th

century biology was the so-called problem of Wallace's line.

Alfred Russel Wallace, co-discoverer with

Darwin of the

principle of

natural selection, believed that between the islands of Bali and

Lombok and then going west of Celebes you could draw a line which

represented the line of convergence between the Austral-Papuan biogeo-graphical zones and the Asian-Malayan zones.

Statistical studies, Ernst Mayr's principally, have disproven this

notion. However, I have collected butterflies and stood in the

forests on both sides of Wallace's line in several places and I

completely understand Wallace's observation and in fact wonder about

Mayr's conclusion. Wallace concluded that these forests are very

different; the bird calls, the butterflies, and the flora - all seemed

different.

But what Mayr seemed to show was that there was no

distinct line. There was a gradient from Australia to Malaya in one

direction and Malaya to Australia in the other direction. Island

groups like this, and I haven't mentioned the Galapagos but they are

another example, are such obvious laboratories of speciation that

when Darwin and Wallace and Walter Henry Bates and other 19th

century biologists who were grappling with the so-called species

problem set out to do their fieldwork, they could not fail to be

impressed by this peculiar theme and variation.

They could not

understand whose fingers strung the harp until they realized that

similar populations separated by catastrophe such as the arrival of

ocean water or a lava flow, then come under very slightly different

selection pressures which cause slightly different physical

characteristics to be taken on. In the Amazon Basin for example, you

can move 2,000 miles and have only about a 15% replacement in

butterfly species. In Indonesia you can cross a strait of water 20

miles wide and have a 17% replacement of butterfly species.

Darwin

and Wallace visited these places, both continental floras and faunas

and the island situations, and through careful observation they

finally understood what the mechanism of speciation was. And it's a

wonderful thing, you know. Take for example butterfly diversity,

that is a situation where diversity itself confers adaptive

advantage. Because butterflies are largely predated upon by birds,

it's been shown in numerous studies that birds hunt a target image.

They have an image of their prey.

If through the chance

recombination of genes your wing color or wing shape pushes you

outside the target spectrum, you will be ignored and survive.

Ralph: Like us!

Terence: And so variety itself becomes a premium in the evolutionary

game. Novelty itself then is preserved because novelty confers an

adaptive advantage in this situation, for birds and butterflies. I

think the implications of these things lie close to the surface.

Earth is a small island, we are making great changes in its

ecological parameters, we are affecting plant and animal

populations. By studying how evolution has shaped island groups, we

can appreciate our own small cosmic island and perhaps eventually

draw politically empowering conclusions from that.

Rupert: What a wonderful overview, Terence. A real delight. There

remains a major evolutionary puzzle. Islands have a tremendous role

in speciation, as all evolutionists believe, and of which both

Darwin and Wallace provided classic examples. Then in places where

there are contacts through island chains the flora can be extremely

species-rich, as in the Malaysian-Indonesian archipelago, one of the

great creation centers of species in the world. That's the kind of

tropical forest I know best, having lived in Malaysia. From what

you've said, this evolutionary creativity arises from a combination

of isolation on islands, plus mingling of two totally radically

different floras, giving rise to all sorts of new possibilities and

combinations.

Terence: And the process was pumped by the repetitive comings and

goings of the sea which repeatedly islanded populations and then

reunited them.

Rupert: And presumably also pumped by the ice ages not only through

changes in sea level, but also through the compression of all forms

of life towards the tropics, followed by a pole-wards migration of

species at the end of each ice age. All this makes sense for the

centre of evolutionary creativity in the Malaysian-Indonesian

archipelago. The problem is that it doesn't explain that other great

centre of evolutionary creativity, the Amazon basin.

Terence: The answer is very simple. It has simply been above ground

a very long time. In other words, the Malaysian-Austro-Papuan

situation is fairly recent, probably the map has looked as it does

no more than 7 or 8 million years. The Amazon on the other hand has

been above water 280 to 300 million years. So simply being in the

tropics with 3, 4, 5 breeding seasons a year for many organisms, and

never being inundated by sea water or catastrophe allowed that

incredible climatic speciation on a continental land mass.

You're

right, it didn't happen as far as we know in Africa, although

Africa's so heavily impacted by human beings that any notion of its

original natural history is impossible. But that's the short answer,

that it was above water a long, long time.

Rupert: But then we have two methods of prolific evolution. One

depends on being around a long time, as in the case of the Amazon.

The other depends on isolation, climatic pumping, mixing of gene

pools and so on.

Terence: What pumped the Amazon situation on a micro level is the

meandering of rivers. You see, it's very hard in a climaxed forest

situation for any new species to gain a foothold. But because rivers

meander and destroy forests and create sand bars and the

intermediate zone of uninhabited land, so-called pioneer species can

move in there.

And that's where the speciation is taking place.

Carl

Sauer estimated that before the advances of human culture it was the

meandering rivers that were the main force for modern plant

evolution on this planet. A vast amount of shifting of boundaries

goes on, and it's in that shifting boundary zone that mutants, new

forms, can get hold. That's why a pioneer plant species will have

the following characteristics. It will be an annual and it will be a

prolific seeder. It will be herbaceous, not woody. In short, it will

be a weed.

And that's what a weed is, a pioneer species, a

tremendously predatory species designed for open land, utterly

unable to compete in the forest, but in open land able to take over

very well.

Rupert: Yes, but while isolation, new environments and so on,

explain one side of evolution, I think there's another side which

Darwinism can't explain, because it puts too much emphasis on

natural selection. J.C. Willis, the great British botanist who

worked in Ceylon and knew the Asian flora well started off as a keen

Darwinian, but was forced to the conclusion that much evolution took

place by divergent mutation, rather than natural selection.

For

example, in Ceylon and India there are many species of water plants

in the family Podostemaceae that live in streams with leaves that

float on water, with many different leaf forms. Any attempt to

account for a particular leaf form in terms of adaptation to water

flow fail because leaves of quite different shape seem to do just as

well, and can flourish side by side.

Terence: Well, the Hawaiian Hapu here is an excellent example. Here

we have the two tree ferns, two distinct species, distributed in a

ratio of 50-50. One has little black stickery stems and the other

has a fuzzy brown soft stem. What selective pressure caused stickers

to work for one and not to work for the other, when they're standing

right next to each other? Seems to me there must be drift of genes

or simply variety for its own sake.

Rupert: Life is constantly trying out new forms. Unsuccessful

novelties are weeded out by natural selection. A few are a wild

success. But many novel forms may work equally well, and survive

equally well, like the two species of tree ferns in your Hawaiian

forest. There may just be lots of equivalent species, where you've

got novelty for novelty's sake. They are not all closely shaped and

sculpted by natural selection.

Ralph: Well, getting back to Hawaii here, it seems, if I understood

you right, that what's unique about Hawaii is the Hawaiian Islands

are young, and they're maximally oceanic islands, far from any

continents. And the process of the population of a new island from a

neighboring island is visible, even in the present, and then we see

a certain pattern is repeated over and over again, even in the

course of a century.

So it seems to me that these different examples

you were talking about conflate two different processes more or less

projected upon the same screen. One is a purely biogeographical

process which could at least be imagined to be operating the same

way without any evolution. We have only the same species that were

found on Maui suddenly appearing on Hawaii by a process of

dispersal.

Some species are successful at pioneering, and help

create an ecology suitable for the second species, and their

space-time patterns are developed one upon another, very interesting

fractal movies that to begin with would have nothing to do with

evolution.

On top of that, you have - I'm not sure about the relative time scales

of this - then you have an evolutionary process involving speciation

either during or after the colonization of a brand new island. Is

evolutionary process essential to the population of the new island

or isn't it?

Terence: I think in the short term it isn't and in the long term it

is. Because many forms of life are arising in these islands, it's

not home free. New arrivals must contend with this kind of islanding

by volcanic flow that I mentioned, and other large-scale

catastrophic events that have gone on in the Hawaiian Islands.

Basically I think that what we see here are genes being mixed and

stirred at a faster rate than in most places and that's without

mentioning the vast number of plants and animal introductions

brought by human beings.

One of the other unique things about Hawaii

that I didn't enumerate is that human beings arrived late and this

absence of long term human impact gives us a clearer picture of

what's happening. It's almost as though Hawaii is a speeded up

microcosm of the earth itself, probably eight-tenths of the big

island is in the pre-archeozoic phase - in other words, almost abiotic

- and

then large areas are covered by lichen, with a fern or two here in

the crevasses.

Ralph: You used the word pumping, and I like that. There's a sort of

a forcing or coupling or a codependence between these different

processes, physical ones, as for example new lava flows, the

meandering of rivers, or the appearance of islands, and space/time

evolutionary processes.

Terence: Really the ice ages are the pump. They raise and lower sea

levels. They create deserts and drop humidity. They force change.

And they are probably driven by fluctuations in the dynamics of the

sun.

Rupert: I should just point out that the evolutionary process looks

rather different if you take

morphic resonance into account. Habit

formation then becomes a much more important evolutionary process.

Individual organisms adapt to new environments. You can take seeds

from a given plant and grow them at different altitudes and in

different climates, and in many places they survive. But in these

different environments, the plants grow differently. Grow them there

over several generations and they develop a new group habit,

stabilized by morphic resonance, without the need for genetic

change.

Terence: Well, adaptive behavior is that small margin of

adjustability that is supposedly not genetically driven.

Rupert: Habit formation and the inheritance of these habits by

morphic resonance could enable evolution to occur much more rapidly

than neo-Darwinians suppose possible, because they ascribe almost

everything to slow statistical changes in gene frequencies. Instead

of mere random mutation and natural selection, you have the positive

adaptation of animals and plants themselves to a new environment.

They often react and respond in a creative way, forming new habits

of life appropriate to the environment. So the creative adaptation

of life to new circumstances, in my view, is not a matter of minor

adjustments. What we are seeing is the innate creativity of life in

action. Not blind, random mutation, not just physical forces, not

just natural selection, but a creativity inherent in all life.

Morphic resonance would enable these new habits to be stabilized and

inherited.

This theory suggests that not only can habits be passed on by

morphic resonance from generation to generation, but also by

morphic

resonance forms and habits could jump from place to place. This

could, for example, help to account for the parallel evolution of

marsupials in Australia with placental mammals on other continents.

Terence: It would augment the natural selection of separated genes

in general.

Rupert: Yes, these things work together. There's still natural

selection of gene pools; but creative adaptation and spread of new

habits take place as well. I suppose the thing about Hawaii that

puzzles me most is why there haven't been more species and more

forms of life in Hawaii. In the rainforest here we see only half a

dozen or so species of tree, whereas in Sumatra or in the Amazon,

there would be hundreds.

Terence: Again, the answer is time

- 200, 300 million years versus 20

million years. That's what it is.

Ralph: There's so many reasons to fail here. I personally find the

environment harsh, lush as it may look to you or other people, and I

suppose that one way a new species could fail is through having bad

habits. There may be habits that manifest visually to us only in

terms of spatial patterns. The colonization of the black lava by the

Ohia tree appears in a certain fractal pattern in which there are

characteristic frequencies of distances that may have to do with the

distance the seeds fly in the wind or something like that.

There is

a certain spatial pattern which is the necessary one for survival

that has a kind of a morphic resonance. I mean there wasn't a

space/time pattern in the physical substrate itself. And other

species, although they would look equally strong or stronger in the

sense of

phylotaxis, when dispersed in the lava they can't make it

because their spatial characteristic is wrong.

So the change of a

species that may not involve DNA could be a change of habit in terms

of the spatial distribution. It could just be response to a nutrient

because of the change in size and therefore characteristic distance

in the space/time patterns. We seem to see that - first we see the

lichen, the lichen creates just a minimum of degradation of the

surface that makes it possible for the Ohia tree to grab hold.

And

the lichen, as the pattern is obviously fractal, sort of

characteristically fractal, and the lava surface is fractal as well,

and fractal means that there's a resonance across scales, then the

lichen scale, which is much smaller - there may be many kinds of

lichen, but only this one grows because its fractal pattern has the

right basic form, something like a time wave, so that as a matter of

fact it's compatible with the bare rock.

And then the Ohia tree is

compatible with its fractal pattern apparently on a much larger

scale which nevertheless resonates harmoniously as opposed to other

species that might be disharmonious. And this harmony, this

capability of a certain space/time pattern, is a habit which may

change and adapt in a way that requires no change in DNA at all, a

nongenetic variation, just dependent on some kind of morphic field.

Rupert: You are talking about the evolution and development of whole

ecosystems. I think what's interesting about this island, the Big

Island of Hawaii, is that this forest ecosystem gets established on

the slopes of the volcano, but is wiped out again and again through

new lava flows. When lava flows are recolonized, an entire

ecosystem has to move, not just single species. So it has to be an

exceptionally portable ecosystem. Maybe that's why it has to travel

light.

Terence: Good point.

Ralph: Coming back to this question of the morphogenetic field of an

entire ecosystem, I just want to ask you about this. In this

creation myth of the Hawaiian Islands ecosystem that you described,

there are islands which have already disappeared and ecosystems have

jumped from them onto Kuai and so on.

But as I understand it, these

islands are rafting along over this more or less stationary hot

spot. Those early islands were right here where we are sitting

today, also very distant from any continental land mass. So is Day

One of biology on the Hawaiian Island chain a result of

long-distance dispersion?

Terence: Yes.

Ralph: Nothing happened until the right lichen arrived after

millions of years?

Terence: Well the lichen I suspect can probably be found in air

samples above any point on the planet.

Rupert: Say you've got spores as the first colonizers.

Terence: Yes, and then the ferns come next, which also propagate by

spores. The reason the non-flowering plants conquered the planet, if

you think about it, is because the planet was like Hawaii. It was

new lava, it was covered with lava flows, and the ferns could get

hold. We think of ferns as soft, somehow spoiled plants. Actually,

they're the toughest plants there are. When we study biology they

teach you about

Psilotum, related to the ancestors of the ferns. The

forest here is full of Psilotum plants, I can point them out to you.

They're tough.

Ralph: But how do they get here? These spores are carried by birds?

Terence: Well sure, by spores. Mud on the feet of migratory birds

could carry millions of spores.

Rupert: The duck's foot theory. More necessary for the transport of

seeds than spores, which are so small and so light that they can be

carried over long distances in the air.

Ralph: Well I think there's a startup problem. I just can't imagine

that the frequency of ducks flying is enough to explain the arrival

of correct species and in the correct temporal sequence. I mean they

would have to be dumping literally dumptruck loads of different

genetic materials on a daily basis on a brand new island in order to

have a chance to get started.

Terence: No, studies with banded birds show that there's a lot of

material moving around and a million years is a long time, a number

of improbable things can go on in a million years.

Ralph: Well I've been here for a week. I have not seen a new species

of bird arrive from the mainland.

Terence: Well stick around.

Rupert: Okay, let's accept the duck's foot hypothesis, especially in

relation to migratory birds. Birds do migrate from place to place

over large distances, including many species in Hawaii, which has

migrants from different continents. But which is cause and which is

effect? No one knows the evolutionary basis for migration.

Terence: No, I don't think it is migratory birds. I think the

process is primarily one of a novelty, unusual events, catastrophe.

The greatest storm of the century, every century.

Ralph: Birds blown

off course.

Terence: Birds blown off course. Now that happens. A single big

storm veering off course might equal a century of ordinary

dispersal.

Rupert: But there are far more regular migrants. And migratory

patterns of birds evolve. For example, new ones have appeared in

Europe in a matter of a few decades, as in the case of the blackcap.

Birds of this species that nest in Germany and Austria traditionally

migrate in the winter to the western Mediterranean. But over the

last 30 years, an ever-increasing proportion migrates to England

instead, where they find abundant food on garden bird tables.

But how would species of migrants find out about Hawaii in the first

place? Rather than individuals being blown here by chance or whole

flocks of them starting out lemming-like from the coast of

California in the hope of finding an island 2,500 miles away, they

may in some way have known that there were islands there to go to.

Perhaps this could happen through a kind of collective map which

they share with other migratory birds.

Some migratory species

knowing about Hawaii may enable others starting off in that

direction to follow a kind of preexisting flight path, rather like

airline flight paths. When we flew here to Hawaii outside the window

about a hundred feet away there was a vapor trail, which we followed

exactly for two hours; it was presumably from the previous jet

flight to Hawaii.

Maybe in bird migrations many species follow the same path, as many

northwestern European species follow the Mediterranean coast of

Spain and cross over the Straits of Gibraltar into North Africa, and

North American migrants tend to follow four main north-south

"flyways."

Maybe when the Hawaiian Islands appeared, long-distance migrants

like albatrosses or other large seabirds noticed them and started

coming here. Somehow this got into a general bird navigation map,

and other species started coming. The appearance of new land

channeled bird migration routes towards it. The word got around and

increasing numbers of species started coming here if only to rest on

the way across the Pacific. Then the ducks' foot hypothesis would be

very plausible.

Ralph: A new island in the Pacific, tell the albatrosses, and the

birds do their job as sort of a pack train to bring as much genetic

material as rapidly as possible and dump it on the new island.

Rupert: Somewhat like an adventure of Doctor Doolittle. But the

question of how migratory birds found Hawaii raises the further

question of the original Polynesian people who found it. One

possibility is that they were keen observers of migrant birds and

noticed that birds set off from their islands in a particular

direction and months later came back again. It would therefore be a

fairly simple deduction that if you followed the migrant birds you'd

reach land sooner or later.

Terence: That's right.

Ralph: That's what "East is a big bird" means. But following the

birds is no less of a mystery than the birds themselves being able

to migrate. So either the people could follow the birds, who

navigate by some unknown mysterious means, or the people could have

had access to similar mysterious means themselves, and when a new

island comes up then the information is somehow injected into their

own migration patterns in their canoe rides from one island to

another.

Rupert: In terms of human migration, these islands are now the limit

of the westward migration of Europeans, having gone right across

North America, subjugating the natives and trying to eliminate their

culture, the whole process has moved here. We can see it happening

before our very eyes, and in evolutionary terms it's the opposite of

everything we've been talking about so far. Now there's no

separation of the islands from the TV networks and other cultural

forces of America.

Terence: One of the most frightening trends I think in modern

culture is the wish to build shopping malls everywhere. There is a

mentality that would like to turn the entire planet into an

international airport arrival concourse. That's someone's idea of

Utopia.

Ralph: There appears to be a double gradient here with the eastward

migration of Asian people balancing the westward migration of

European people, and this is actually the interface where the double

gradient can produce an increase in novelty and new mutations, and a

forward leap perhaps, of human evolution, could begin here.

Terence: A standing wave forming here as forces move both east and

west.

Rupert: So can we point to any human creativity in Hawaii which

exemplifies the cultural equivalent of the Malaysian Archepelego? Or

is it more like a stalemate with roughly half of the island's

population coming from the East and half with the West, with the

native Hawaiians trapped in between?

Terence: Well, a Pacific Rim culture is hypothesized to be emerging,

and Hawaii is central to all of that. It's equidistant from Sydney,

Lima, Tokyo, and Vancouver.

Rupert: Have they adopted the slogan, "Hawaii, the Pacific Hub" ?

Terence: If they haven't, I'm sure they're not far behind. The

presence of the world's largest telescopes here make it a center of

world science, at least in astronomy. I think the world's first,

second and third largest telescopes are on this island, with an

identical twin of the largest being built 200 yards away from it.

Rupert: So it's a centre for linking humanity with the stars.

Terence: We're looking out from the top of Hawaii, chosen

paradoxically for being the darkest place on earth.

Ralph: From here they'll see the next wave of ducks' feet departing

for Biosphere II.

Back to Contents

Chapter 4 - Homing Pigeons

Rupert: In my book,

Seven Experiments That Could Change The World,1

I focus on areas of research that have been neglected by orthodox

institutional science because they don't fit into its present view

of the world. As we have already discussed (Chapter 1), this

research can be done on very low budgets.

The experiment I propose with homing pigeons is one of the most

expensive in the book, but even so need cost no more than about

$600. In spite of over a century of research, we really haven't a

clue how homing pigeons find their way home. You can take a homing

pigeon 500 miles from its loft and release it, and it will be home

that evening if it's a good racing bird.

Pigeon racing enthusiasts

do this regularly. The birds are taken away from the homes in

baskets on trains or on lorries. Then the baskets are opened, the

pigeons circle around and fly home. It's a very competitive sport.

Pigeon fanciers win cups and cash prizes, and good racing birds can

sell for as much as $5,000.

Pigeon homing is a phenomenon that everyone agrees is real.

Moreover, many other species of birds and animals can home,

including dogs and cats, and even cows. But no one knows how they do

it. Charles Darwin was one of the first to put forward a theory. He

proposed that they do it by remembering all the twists and turns of

the outward journey.

This theory was tested by putting pigeons in

rotating drums, and driving them in sealed vehicles by devious

routes to the point of release. They flew straight home. They could

even do this if they were anesthetized for the duration of the

journey. The birds could still fly straight home. So these

experiments eliminate theory number one.

Another theory is that they do it by smell. This is not

intrinsically very plausible, since, for example, pigeons released

in Spain can home to their loft in England downwind from the point

of release. There is no way the smells could blow from its loft in

England, to Spain, against the wind, but the birds get home.

Experimenters have blocked up pigeons' nostrils with wax, and they

get home. They've severed their olfactory nerves, poor birds; they

still get home.

They've anesthetized their nasal mucosa with xylocaine or other local anesthetics, and they get home just the

same. So smell cannot explain their homing abilities.

The next theory is that they do it by the sun, somehow calculating

latitude and longitude from the sun's position. To do this they

would need a very accurate internal clock. Well, pigeons can home on

cloudy days, and they can also be trained to home at night. They

don't have to see the sun, or even the stars. If they can see the

sun, then they use it as a kind of rough compass, but it is not

necessary for homing. You can shift their time sense by switching on

lights early in the morning, and covering their loft before sunset.

For example you can shift their sense of time by six hours. Now if

you take such birds away from home and release them on a sunny day,

they set off roughly 90 degrees from the homeward direction, using

the sun as a compass. However, after a few miles they realize

they're going the wrong way. They change course and go home.

Then there is the landmark theory. The use of landmarks is

inherently unfeasible, because if you release the birds hundreds of

miles from where they've been before, landmarks can't possibly

explain their finding their home, although they undoubtedly use

landmarks when they're close to home, in familiar territory. In any

case, this theory has been tested to destruction, by equipping the

pigeons with frosted glass contact lenses, which mean they can't see

anything at all, more than a few feet away.

Pigeons with frosted

glass contact lenses can't fly normally, and indeed many refuse to

fly at all. Those that will fly do so in a rather awkward way.

Nevertheless, such birds can be released up to 100 miles away or

more, and although some of them get picked off by hawks, others can

get within a few hundred yards of the loft. They crash into trees or

telegraph wires, or flop down onto the ground, showing that they

need to see the loft in order to land on it.

But the amazing thing

is that they can get so close when they are effectively blinded.

Sometimes they overfly the loft, and then within a mile or two,

realize they've gone too far, turn around and come back.

This leaves only the magnetic theory. Until the 1970s, most

scientists were very reluctant to consider this possibility, because

magnetism sounded too like "animal magnetism," mesmerism, and a

whole range of fringe subjects they didn't want to mess with. It

also seemed unlikely that pigeons could detect a field as weak as

the earth's.

However, it has been shown that some migratory birds

can indeed detect the earth's magnetic field; they do seem to have a

kind of compass. However, even in principle, a compass sense cannot

explain homing. If you had a magnetic compass in your pocket, and

you were parachuted into a strange place, you'd know where north and

south were, but you wouldn't know where home was. You would need a

map as well as a compass, and you would need to know where you were

on the map.

But perhaps the pigeons have an extraordinarily sensitive magnetic

sense, by which they can measure the dip of the compass needle. A

compass needle points straight down at the north pole and is

horizontal at the equator; the angle of dip depends on the latitude.

So if pigeons not only have a compass but can measure the dip of the

needle, they might be able to work out their latitude. This could,

in theory, enable them to know how far north or south they had been

displaced.

But if they are taken due east or west of their home, the

angle of the field is exactly the same as at home, and pigeons can

home equally well from all points of the compass.

In spite of these inherent theoretical difficulties, the magnetic

theory has been taken seriously by many scientists, not because it

is particularly convincing, but because they think there must be

some mechanistic explanation, and this is all that's left.

Nevertheless, this theory too has been refuted by experiment.

To

disrupt the magnetic sense, pigeons have been treated experimentally

in two ways.

-

Firstly, they've had magnets strapped to their wings or

their heads, in order to disrupt any possible magnetic sense.

-

Secondly, they've been degaussed by being put in extremely strong

magnetic fields that will disrupt any magnetically sensitive parts

within them. These demagnetized pigeons and pigeons with magnets

strapped to them can still get home.

(The first experiments of this

kind in the late 1970s seemed to show that magnets could reduce

their ability to home on cloudy days; however, these initial results

turned out to be unrepeatable, and many experiments have now shown

that pigeons can home, even on cloudy days, when any possible

magnetic sense is disrupted).

That's the current state of play. Every hypothesis has been tested,

and tested to destruction. They've all failed.

The one remaining

that you occasionally hear is,

"They can hear their home from

hundreds of miles away, because of extremely sensitive hearing."

Even this won't work, because pigeons that can't hear can still get

home. All the theories have failed. Nobody has a clue how they do

it, although this ignorance is often covered up by vague statements

about "subtle combinations of sensory modalities," without giving

any details as to what this might mean.

Pigeon homing is the tip of the iceberg. There are many other

phenomena to do with migratory and homing behavior in animals which

are unexplained, including the migration of cuckoos, Monarch

butterflies, salmon, and so on. Human beings may also have a

directional sense, probably best developed in nomadic people like

Australian Aborigines, South African bushmen, and Polynesian

navigators, and least developed in modern urban people. In summary,

pigeons, like many other animal species, seem to have navigational

powers which are inexplicable in terms of known senses and physical

forces.

The experiment that I'm proposing is very simple, and I can outline

it briefly. The evidence suggests there is an unknown sense, force

or power, connecting the pigeons to their home. I think of it as a

kind of invisible elastic band, stretched when the birds are taken

away from their homes, pulling them back and giving them a

directional sense.

I'm not bothering at the moment to theorize about

the possible physical basis of this, whether it's part of existing

physics, an extension of nonlocal quantum physics, or whether it

requires a new kind of field. That question is open.

Using this simple model of an invisible connection, the experiment

I'm proposing is the converse of those done so far. The usual

experiments involve taking the pigeons from the home, and watching

them return. By contrast, my experiment involves taking the home

from the pigeons, using a mobile pigeon loft, which is essentially a

shed mounted on a farm trailer.

I've actually done this experiment, first in Ireland and secondly in

eastern England. So far, I haven't been able to carry it past the

first training phase. I found, however, that it is possible to train

pigeons to home to a mobile loft. They don't expect their home to

move any more than we do, and the first time you take them out, you

move their home just a hundred yards.

When you release them they can

see perfectly well that it's not where it was before. They go on for

hours flying round the place where it was before, until they go into

the loft in its new position. That's just how we'd behave if we went

home found our house a hundred yards down the street. Most of us

wouldn't just go straight in; we'd probably go round and round in

circles, around the place where it was before, looking awfully

puzzled.

That's what pigeons do. If you keep doing this, after three

or four times, they just get used to it, realizing they're nomads or

gypsies now. After this kind of training, they can find their home

up to 2-3 miles away within ten minutes and go straight in.

During the First World War the British Army Pigeon Corps had 200

mobile lofts in converted London buses. There's still one army that

uses mobile pigeon lofts, the Swiss army, and they are doing some

fascinating research. Unfortunately some of it is classified, being

a military secret.

To go forward with the experiment, after you've trained the birds,

you move the mobile loft 50 miles downwind from the point of

release, so they can't smell it. If the pigeons find it quite

quickly, flying straight there, this would suggest there's an

invisible connection between them and their home. The next question

would be, is it between the loft itself, or the other pigeons? To

test this you leave some of their nearest and dearest in the loft,

or you take the nearest and dearest somewhere else, to seeing

whether they find the nearest and dearest, or whether they find the

physical structure of the loft.

How the experiment will turn out, I don't know. If there's a new

power force or sense involved, what might it imply? What might it

tell us? Where would we go from there? This is the question I want

to raise with you.

Ralph: Let me ask you for a couple of details. When they race the

pigeons and these home lofts are all in different cities, different

streets, and so on, how does it work? Does the wife of the pigeon

racer sit at home and when the mate comes, pull out the cellular

telephone and call headquarters?

Rupert: The racing pigeon has a little ring on its leg for the race,

with its number and the race number. When it enters the loft, the

pigeon fancier captures the bird, takes this ring off, and using a

sealed time clock issued by the local racing pigeon federation,

stamps the ring with the time it comes home. When they send in these

tags with the time stamps they calculate from the point of release,

the straight-line distance to each loft, divide the distance by the

time, and get the average speed.

Ralph: Do they account for difficulties and anomalous obstacles

encountered along the way?

Rupert: No. If they're killed by a sparrow hawk, they don't win the

race.

Ralph: Does the home loft that they're racing to contain family

members?

Rupert: Yes.

Ralph: There's a whole bunch of pigeons in the loft, and only one or

two of them are racing?

Rupert: There are several racing systems. The birds need a motive to

go home fast. In the winter, they don't home very well. Races are

usually held in the spring or the summer when they've got mates,

eggs and young, so they have an incentive to get back to their

family. One widely practiced method is called the jealousy system,

dependent on the fact that pigeons are monogamous, forming pairs

that last at least for a year.

The pigeon owners wait until the

birds have paired up, then they take away the bird that they're

racing, and let another bird approach its mate. Then the racing bird

is taken away. When released it returns home really fast.

Ralph: The stronger the motivation, the tighter the morphogenetic

elastic band.

Rupert: Yes.

Ralph: Now that I'm getting the elastic band theory down I'm ready

to risk speculating on the question. This is my fantasy.

First of all, accepting the premise that ordinary fields won't do as

an explanation, let's assume it's a kind of ESP. I'm thinking of

bats, which have been studied in a room just like this one, with

wires strung through it. In the daytime the bat will fly around

missing the wires and avoiding the wall, using vision primarily, we

suppose. At night they do the same thing without vision, using

sonar.

Suppose, based on bats, that the brain and the mind are able

to image the results of sonar experiments, in the same kind of image

that the eyes form. In other words, instead of only hearing the

sound and trying to compute where the echo's coming from, the bat

actually sees the room with its ears, in the same kind of

representation as the visual. Then if somebody suddenly turns the

lights on, the bat wouldn't hesitate and fall to the ground because

it has to switch from system A to system B.

The visual

representation of the room would exactly overlay the sonar image.

Similarly, dolphins have this huge melon-shaped sensory organ that

receives sonar waves. Both in the case of bats and dolphins, the

visual/sonar representation is more three-dimensional than ours.

This would give them, in a way, a kind of a higher IQ.

Dolphins and

whales, who also use sonar, may sense almost the entire planet as a

three-dimensional object, with its curvature and so on.

If there were a sixth sense that homing pigeons and monarch

butterflies have, and maybe us to a degree, then I'd suppose it

would work like that. Going back to our pigeons, after they're

rotated, doped, transported 500 miles and released, with this sixth

sense it would consult a very detailed three-dimensional road map of

the entire planet, orienting the holographic three-dimensional image

with the visual world, rotating things around to get them aligned,

and then flying in the map.

Things like smells, the sun, the

magnetic field, are factors, and they'll act as a kind of label on

the map.

This still doesn't explain how they get home. They would have to

know where home is marked on the map. Given a sixth sense with a

complete road map of the world as a three-dimensional object

containing smells, trees, magnetic fields, the sun and the celestial

polar constellations and so on, there must be some kind of beacon

where home is supposed to be. Even in this sixth sense theory, that

remains a mystery. The pull of some sort of morphogenetic rubber

band is one idea, if there's an obstacle between pigeon and loft,

there would have to be some way to find a way around it.

I think the rubber band theory is too simple. Considering jealousy

and so on, the longer the rubber band is pulled, the tighter it

gets, which is the opposite of most fields that we know, where the

farther you get away from home, the weaker is the pull. I would

think that the rubber band is more like a beacon that's a part of

this whole field. Then the question is how is the physical

information of a location, especially a recently moved location,

inserted into the field.

This would be the final mystery to fill in

the picture.

Terence: It seems to me, if I can download this into language, that

the problem is not with the pigeon, but with the experimenter. We

know from studying quantum mechanics that things are not simply

located in space and time. This error is what Whitehead called the

fallacy of misplaced concreteness. I've always felt that biology is

a chemical strategy for amplifying quantum mechanical indeterminacy

into macrophysical systems called living organisms.

Living organisms

somehow work their magic by opening a doorway to the quantum realm

through which indeterminacy can come. I imagine that all of nature

works like this, with the single exception of human beings, who have

been poisoned by language.

Language has inculcated in us the very

strong illusion of an unknown future. In fact the future is not

unknowable, if you can decondition yourself from the assumption of

spatial concreteness.

The answer to how the pigeon finds its way home is that a portion of

the pigeon's mind is already home, and never left home. We, gazing

at this, assume that pigeons, monarch butterflies, and so forth, are

simpler systems than ourselves, when in fact, our assumption of the

unknowability of the future creates a problem where there is no

problem. It's only in the domain of language, and perhaps only the

domain of certain languages, that this becomes a problem.

To put it simply, if you had the consciousness of a pigeon, you

would not have a diminutive form of human consciousness, you would

have a consciousness that we can barely conceive of. The

consciousness of the pigeon is a continual awareness extending from

birth to death, and the particular moment in space and time in which

an English-speaking person confronts a pigeon is, for the pigeon,

not noticeably distinct from all the other serial moments of its

life.

The problem is in the way the question is asked, and in the

way human beings interpret the data that is deployed in front of

them. After all, in the animal world, the future is always rather

like the past, because novelty tends to be suppressed. Most things

that happen have happened before and will happen again.

My

expectation would be that what we're seeing when we confront these

kinds of edge phenomena in biology is a set of phenomena which, when

correctly interpreted, will bring the idea of quantum mechanical

biology out from the realm of charge transfer, intracellular and subcellular activity, and into the the domain of the whole organism.

I'm not sure this is the solution, but it does cause the problem to

disappear.

Ralph: Are you saying that the entire life history of the pigeon is

more or less determined at the outset, including the trip away from

the loft and the trip back?

Terence: It never went anywhere. It's only when you've laid over

this a three-dimensional grid imposed by language that there appears

to be a problem. In other words, there's some kind of a totality

involved, but we section and deny it, and then come up with a

dilemma.

Rupert: What about the pigeons that get picked off by sparrow hawks

on the way home?

Terence: They doubtless see that as well. The real question I'm

raising is to what degree does language create the assumption of an

unknown future? To what degree does it dampen a sense of the future

that I imagine to be very highly evolved in the absence of language?

Rupert: It's hard for me to grasp. Do you mean that when a pigeon is

released, part of its mind is still at home, in the future, and this

in some sense helps it to get back to the loft?

Terence: You and I have talked about this before. You've always

implied that the morphogenetic fields drive, push from behind.

Rupert: No, I've always said they pulled from in front.

Terence: Then they're attractors. I am partly saying that, and

partly that the consciousness of the organism is distributed in time

in a way that makes it capable of doing miracles from our point of

view. From its own point of view, there's nothing unusual going on

at all.

Ralph: You wouldn't be at all surprised if, as a matter of fact, the

race was won by a clever pigeon that actually vanished at the point

of release and simultaneously appeared back in the loft.

Terence: You're seeing it as some kind of virtual tunneling, as an

amplified quantum mechanical effect. Perhaps this is the solution to

the spontaneous combustion mystery. We pay great lip service to the

idea that quantum mechanics is very important for life and so forth.

Well, the mechanical nature of things at a quantum physical level

suggests that if life is an application of those processes, then our

apparent entrapment in three-dimensional space with an unknown

temporal dimension is almost, you would say, habitual, not

intrinsic. This seems very reasonable to me.

Ralph: I think your idea is good. I like it. If consciousness

extends over a certain span of time, even a few days, it would

explain a lot of things in the pigeon world. I still think it's

important to know whether the future is totally determined, or if

the consciousness of the future includes several alternatives. In

the case of several alternatives, sooner or later the pigeon is

presented by a fork in the road and has to decide which way to go.

I

think we're still missing here some kind of mechanism for the pigeon

to follow the stretched rubber band of its own consciousness,

occupying an extended region of space and time, so that its ordinary

physical body ends up back where its consciousness ends. How does it

do it?

Terence: An analogy would be when you run a cartoon or a film

backwards, and there's a spectacle of wild confusion, but

miraculously, everything manages to end up in the right place. It

isn't that there really aren't choices for a pigeon when it comes

into awareness, but that it comes into all the awareness it will

ever have. It's like having your deathbed memories handed to you at

the moment of birth.

Essentially, for the pigeon, it's a kind of

play. It knows what's going to happen, its life unfolds as

anticipated, but it doesn't even know that it knows. The pigeon

doesn't have the concept "anticipated." It's we who are observing

that have that concept, and we alone are tormented by an anxiety of

the unknowable future, an artifact of culture and language.

Things

like monarch butterflies, pigeon homing, and some of these other

phenomena are clues to us that imputing our consciousness into

nature creates problems in our understanding.

Ralph: That means that except for ignorance caused by the power of

language, we would have the consciousness of a pigeon and therefore

see our entire lifetime. According to this view, the baby pigeon

chick, upon pecking out the shell, is waking from a dream, looking

around and realizing that, "Oh damn, I'm the one that's going to

have to race three years from now and they're going to put this

other jerk in there with my mate."

Terence: You use language to portray the state of mind of the

pigeon. That immediately collapses its four-dimensional vector into

three dimensions and it becomes no longer a pigeon, but a person

talking like a pigeon.

Ralph: Is the pigeon then aware or unaware of its entire history

from birth until death?

Terence: It's aware, but it's not aware that it's a history.

Ralph:

Experienced as one timeless moment.

Terence: We could go further with this and say this explains our own

curious relationship to the prophetic and anticipated. Instead of,

like the pigeon, having a 95% clear view of the full spectrum of our

existence, by opting into language we have perhaps a 5% view of the

future. We're tormented by messiahs and prophecies, and we lean

toward astrology and computer modeling and all of these advanced

tools that give us a very weak and wavering map of the future which

we pay great credence to and worry a great deal about.

I'm

suggesting that if we could step away from language that we'd fall

into a timeless realm where darkness holds no threat and all things

are seen with a kind of great leveling and all anxiety leaves the

circuits.

Perhaps this is what Zen masters do and teach.

I'm suggesting one more version of The Fall. From the fourth

dimensional world of nature, complete in time, we fell into the

limited world of language and an unclear future and hence into great

anxiety and conundrums like how do the pigeons find their way home.

Ralph: This suggests that we should stop talking and writing books

and just hum.

Terence: I've always felt that. Rather like a pigeon.

Ralph: Is this a polite way of saying that Rupert's current book and

homing pigeon experiment is a total waste of time even if it only

costs $10?

Terence: I think all experiments as currently understood are futile,

because all, including I assume the experiments in Rupert's book,

make the assumption that time is unvarying, and I don't believe that

time is unvarying. I didn't intend to open this up on a general

frontal attack of the epistemic methods of modern science, but in

fact the idea that time is invariant is entirely contradicted by our

own experience and is merely an assumption science makes in order to

do its business.

Ralph: I believe that we have a case here of multiple personality in

action and now I'm going to undertake to prove it. You are now

suffering from hay fever. Suppose that Rupert had in his book an

eighth chapter on an experiment with homeopathic medicine, and the

outcome of it was that a flower power was discovered which

absolutely and instantly cures hay fever. Would you then be

interested in the result?

Terence: Sure, but as a practical matter, I don't think we should

confuse our ideologies with our sinuses. You see, I would like to

redefine science as the study of phenomena so crude that the time in

which they are imbedded is without consequence. I suppose ball

bearings rolling down slopes fall into this category.

The things

which really interest us; love affairs, the fall of empires, the

formation of political movements, happen on a different scale, and

there's no theory for much of what happens in the human world. In

the human world the invariance of time forces itself upon us, so we

create categories of human knowledge outside of time, like

psychology or advertising or political theory, that address the

variable time that we experience.

Then we hypothesize a theoretical

kind of time, which is invariant, and that is where we do all the

science that leads us into these incredibly alienating abstractions.

This goes back to Newton, who said time is pure duration. He

visualized time as an absolutely featureless surface. Now take note

that Plato's effort to describe nature with perfect mathematical

solids was abandoned long ago, because nowhere do we meet perfect

mathematical forms in nature. The only perfect mathematical form

that has been retained in modern scientific theory is the utterly

unsupported belief that time, no matter at what scale you magnify

it, will be found to be utterly featureless.

There is absolutely no

reason to assume this is true, since all experiential evidence is to

the contrary. The problem is, if we ever admit that time is a

variable medium, a thousand years of scientific experiments will be

swept away in an instant. It's simply a house of cards that's better

left where it stands.

Rupert: This seems to go a little bit beyond the problem of pigeon

homing.

Terence: It addresses the problem of experiments as a notion.

Rupert: If we take what you are saying down to the level of pigeons

again, it turns out to be an elaborate version of the rubber band

theory; "the rubber filigree," or something like that. Let's say we

perform the experiment of moving the loft; it could show us

something that goes beyond anything contemporary science would

expect. It might or might not fit with your all-time theory.

Terence: It does fit.

Rupert: Nevertheless, here we have an experiment, crude though it

is, which would show that the existing scientific model is very

inadequate. The rubber band theory involves a kind of attraction to

the home and in that sense involves a pull in time, so it does raise

all these questions about the nature of time.

Terence: Do you have a theory about how it works? I don't see how

morphogenetic fields are particularly helpful here.

Rupert: Yes. I think the morphogenetic field would include both the

pigeon and its loft. You can separate them by moving the loft or by

moving the pigeon. Either way, they're part of a single system. The

pigeon's world includes its loft, its home, its mate, and all the

rest of it. When you move them, they're now separated parts of a

single system, linked by a field. The pigeon is attracted within

this field, back toward the home which functions as an attractor.

This is where Ralph and I have a different view of attractors. The

pigeon is pulled back toward the field, not needing a road map of

the whole of Britain. A road map is irrelevant. It just feels a pull

in a particular direction.

Ralph: It's like the angel theory; that when I come to a fork in the

road, a guiding angel appears from behind a tree and tells me which

way to go.

Rupert: Roughly speaking, it is. You just feel a pull in a

particular direction. You don't even think about it. I think that's

how the pigeon does it, subjectively. I don't think it necessarily

needs to see the whole of its future from egg to grave. I think it

feels a pull towards home by this kind of invisible rubber band,

which is actually like a gradient within the field towards an

attractor which is its home.

That's how you'd model it

mathematically. You wouldn't have to bring in the whole of the rest

of Britain and a road map. If it did, however, need a road map to

the whole of Britain or Europe, we'd have to ask the question how

would it get it? It might tune into the collective memory of all the

other pigeons that have ever gone on homing races. If a pigeon could

access the collective pigeon psyche, or the collective memory of

other species; if all birds could link up to what all other birds

could see, then they would indeed have access to a global map of the

world.

I think that's probably going further than we need in this

rather limited case.

In the case of young cuckoos migrating in the autumn from Britain to

South Africa, independent of the parents that they leave a month

earlier, they must be tuning in at least to a kind of collective

cuckoo memory that includes features of the landscape over which

they fly. The rubber band theory wouldn't necessitate even that.

Ralph: There still seems to be a mathematical or cognitive problem,

when the loft is moved. The dynamical system, which extends

essentially over the whole of the planet, wherever the pigeon may be

released, has to receive the feeling of which direction to go. The

question arises, how does the attractor, the loft, extend its field

and directional instructions all over the planet? I don't think that

the idea of morphic resonance helps here, because in the case of the

moving loft, no other pigeon has flown to it.

Rupert: I'm not talking about morphic resonance, I'm talking about

the field itself. morphic resonance is a memory. Say you have a pile

of iron filings and a magnet. The filings are drawn toward the

magnet and you see lines of force between them. When you move the

magnet, you see an immediate response.

Ralph: The loft itself simply functions as a magnet in another field

which is not an electromagnetic field; a sort of emotional field.

Rupert: When you move the loft and it's just like moving a magnet.

Automatically the iron filings or whatever respond. That's basically

the model I'm suggesting.

Ralph: And the reason that I can't find my car in the parking garage

is because I'm not emotionally attached to it and I've never been in

love with it. I should get an Italian car.

Rupert: In the human realm it could apply to finding people. My wife

Jill does an experiment in her workshop where people form pairs and

they first find each other by humming with their eyes closed. After

they've got that, they find their partner just by feeling where they

are and heading in that direction. I've tried doing this experiment

with our children on the assumption that with children this effect

might be very strong, and it turned out one of them was extremely

good at finding me. Then I discovered he was peeping.

Maybe bonds between pigeons and their homes are comparable to the

bonds between people and other people. Indeed, they may be related

to the kind of social bonds that hold society together. When we say

the bonds between people, we may mean something more than a mere

metaphor.

Perhaps there is an actual connection. We have many

examples from the human realm, as when a child falls ill miles away

and its mother immediately starts worrying and rings up to find out

what's happening. This may be another manifestation of the same kind

of rubber band effect. It may be an aspect of social bonding.

The

motive of pigeons to go home is social, not merely geographical. If

it hasn't got mates, it doesn't bother. In the case of migratory

birds, bees that have to forage out from their hives and then come

back, there must be some way in which the social bonds extend into a

geographical dimension and then become spatial, directional bonds to

find the home group.

There are cases reported by naturalists that when packs of wolves go

out hunting, a wolf may be injured, and stay behind in a kind of

lair. The pack goes on and kills an animal, quite silently, no

baying. Then the wounded wolf take the shortest line from where it

was to the place of the kill and joins the rest of the pack for its

meal.

The tracks show that it goes in a straight line without

following scents, because it can do this when the wind is blowing

the wrong way. This kind of social bond and linkage may be

fundamental.

Ralph: There's a kind of agreement here that there is a sixth sense

that's a field phenomenon, like the quantum field. It's a social

field, involved with the flocking of birds, the schooling of fish,

and with herds of animals and packs of wolves. To answer the

question you posed when you started us off; what would this teach

us, or mean to us in terms of our future?

It could be that humans

are somehow divorced from the significance of this field, so

whenever their guardian angel speaks, they always do the opposite.

If we want to understand the population explosion, the demise of the

planet, all these wars, the manifestation of hatred and sources of

evil, a candidate for the disharmony in the human species would be

its disconnection with this field. Here's where Terence's idea comes

in, that somehow to submit to language is to lose our connection

with the field.

We've all done experiments in not speaking, for

example meditation and dreaming, where the antitheses of language

has an opportunity to come forward and re-connect us to this field.

For people like Americans, who watch television seven hours a day,

there may somehow not be enough time away from language.

Terence: Notice that most prophetic episodes are dreams. This

supports my point, that we've lost connection with a kind of

fourth-dimensional perception that for the rest of nature is

absolutely a given.

Rupert: Why do you think it's a given in the

rest of nature?

Terence: Because there are many, many cases of this kind of thing.

Animals that are put in the pound by the owners who are moving, and

then the owners move seven hundred miles and the animal escapes from

the pound and it doesn't return to the ancestral home; it returns to

the new apartment in a different city.

The monarch butterflies, the

homing pigeons, a whole host of mysterious phenomena become utterly

transparent and trivial if you simply hypothesize that for them, the

future doesn't have this occluded character that it has for us as a

result of our acquiescence in language behavior.

Rupert: It's not just a problem in time, it's a problem in space.

Terence: They see themselves at every point in their life, not just

the high or low points.

Ralph: They're a minute ahead of where they are, so they just go

that way.

Terence: In other words they can always see their goal from where

they are. They navigate through time in the same way that we

navigate through space. I mean, if you were a two-dimensional

creature, the things that we do, navigating in three-dimensional

space, would be absolutely mysterious and generate all kinds of

metaphysical speculation and hypotheses.

Why should nature imprison

itself within a temporal domain?

Clearly, for us it's an artifact of

language. We talk about future tenses, past tenses that aren't

descriptive of the future and the past; they create it. That's why I

put in the possible exception of human languages where this is not

happening and therefore they are much closer to animal perception.

The "mysterious" behavior of Australian aborigines, or the Hopi.

These people seem capable of things that to us are like magic, but

the magic is all done by knowing what's going to happen. If they

simply imbibe the animal's understanding, then to them it's trivial.

This is the most elegant explanation, not requiring new, undetected

fields, or any of these other somewhat cobbled-together mechanisms.

Rupert: Just another dimension.

Terence: We know it's there. There's no debate about that. I've

always noticed that all the magic done by shamans in aboriginal

society, especially the ones that are using psychoactive plants,

suddenly becomes not so mysterious if you simply assume that, by

perturbing the ordinary brain states and ordinary language states,

they let in this hyper-dimensional understanding. Look at what

shamans do; they predict weather and they tell the tribe where the

game has gone, both requiring a knowledge of the future.

They rarely

lose a patient, meaning they know who's going to make it and who

isn't, so they can refuse all cases destined to be fatal. All these

examples of shamanic magic can easily be explained by the simple

assumption that they can to some degree perceive the future. Animals

operate from this place to begin with. What is the shaman's strategy

for attaining his special knowledge?

He becomes like an animal, he

is master of animals, he dresses in skins, he growls.

Ralph: He talks to pigeons.

Terence: He talks to the animals, perturbing his brain state with

ordeals or drugs or other techniques. The very close association of

the shaman to the animal mind suggests that it's the clue to

entering this atemporal or fourth dimensional perceptual sphere.

Rupert: In the Christian tradition the principle symbol of the holy

spirit - that which gives inspired prophecy, shamanic-type gifts of

healing, all the gifts of the spirit, including speaking in tongues,

prophecy, healing, and intuitions of various kinds - is the pigeon.

The first Biblical story of the pigeon is in the story of Noah's

ark, where the pigeon was sent off and came back with the olive

twig.

Right from the beginning the pigeon is a messenger who can

find out things in distant places and return, bringing back the

information.

You could say that central to the whole Western

tradition, this shamanic thing of becoming like an animal, in this

case somehow entering the mind of a pigeon, or in some way

assimilating to the state of the pigeon, is the basis of the gift of

knowledge, prophecy, and spiritual power.

Notes

1 Rupert Sheldrake,

Seven Experiments that Could Change the World

(London: Fourth Estate, 1994).

Back to Contents

Chapter 5 - The World Wide

Web

Ralph: I first fell in love with the World Wide Web in the winter of

1993-94 ,when it was about one year old. And my obsession with the

Web grew so rapidly that I have written a book on it called

The Web

Empowerment Book.

My motive was to wake people up to the existence

of this thing before it's too late, and get them involved in order

to participate in the creation of our future. But when I go around

trying to tell people about it they say,

"Well what is it? And how

is it different from the Internet?" and so on.

I'll start by trying

to tell you this.

By now everybody is familiar with the Internet. It's on the cover of