|

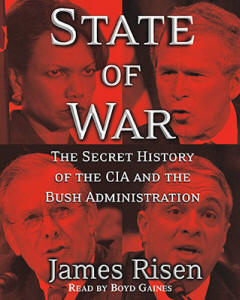

by James Risen January 2006 from TheGuardian Website

She had probably done this a dozen times before. Modern digital technology had made clandestine communications with overseas agents seem routine.

Back in the cold war, contacting a secret agent in Moscow or Beijing was a dangerous, labour-intensive process that could take days or even weeks. But by 2004, it was possible to send high-speed, encrypted messages directly and instantaneously from CIA headquarters to agents in the field who were equipped with small, covert personal communications devices.

So the officer at CIA headquarters assigned to

handle communications with the agency's spies in Iran probably didn't think

twice when she began her latest download. With a few simple commands, she

sent a secret data flow to one of the Iranian agents in the CIA's spy

network. Just as she had done so many times before.

The CIA officer had made a disastrous

mistake. She had sent information to one Iranian agent that exposed an

entire spy network; the data could be used to identify virtually every spy

the CIA had inside Iran.

On the heels of the CIA's failure to provide accurate pre-war intelligence on Iraq's alleged weapons of mass destruction, the agency was once again clueless in the Middle East.

In the spring of 2005, in the wake of the CIA's

Iranian disaster, Porter Goss, its new director, told President Bush

in a White House briefing that the CIA really didn't know how close Iran was

to becoming a nuclear power.

The story dates back to the Clinton administration and February 2000, when one frightened Russian scientist walked Vienna's winter streets.

The Russian had good reason to be afraid. He was

walking around Vienna with blueprints for a nuclear bomb.

It was one of the greatest engineering secrets

in the world, providing the solution to one of a handful of problems that

separated nuclear powers such as the United States and Russia from rogue

countries such as Iran that were desperate to join the nuclear club but had

so far fallen short.

The CIA had given him the nuclear blueprints and then sent him to Vienna to sell them - or simply give them - to the Iranian representatives to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

With the Russian doing its bidding, the CIA appeared to be about to help Iran leapfrog one of the last remaining engineering hurdles blocking its path to a nuclear weapon.

The dangerous irony was not lost on the Russian

- the IAEA was an international organization created to restrict the spread

of nuclear technology.

The CIA was placing him on the front line of a

plan that seemed to be completely at odds with the interests of the US, and

it had taken a lot of persuading by his CIA case officer to convince him to

go through with what appeared to be a rogue operation.

Should he expect to be hauled before a congressional committee and grilled because he was the officer who helped give nuclear blueprints to Iran?

The

code name for this operation was Merlin; to

the officer, that seemed like a wry tip-off that nothing about this program

was what it appeared to be. He did his best to hide his concerns from his

Russian agent.

In a luxurious San Francisco hotel room, a

senior CIA official involved in the operation talked the Russian through the

details of the plan. He brought in experts from one of the national

laboratories to go over the blueprints that he was supposed to give the

Iranians.

He said the CIA was mounting the operation simply to find out where the Iranians were with their nuclear program. This was just an intelligence-gathering effort, the CIA officer said, not an illegal attempt to give Iran the bomb.

He suggested that the Iranians already had the

technology he was going to hand over to them. It was all a game. Nothing too

serious.

But Tehran would get a big surprise when its scientists tried to explode their new bomb. Instead of a mushroom cloud, the Iranian scientists would witness a disappointing fizzle. The Iranian nuclear program would suffer a humiliating setback, and Tehran's goal of becoming a nuclear power would have been delayed by several years.

In the meantime, the CIA, by watching Iran's

reaction to the blueprints, would have gained a wealth of information about

the status of Iran's weapons program, which has been shrouded in secrecy.

Within minutes of being handed the designs, he had identified a flaw.

His comments prompted stony looks, but no straight answers from the CIA men.

No one in the meeting seemed surprised by the

Russian's assertion that the blueprints didn't look quite right, but no one

wanted to enlighten him further on the matter, either.

During a break, he took the senior CIA officer aside.

The CIA case officer couldn't believe the senior

CIA officer's answer, but he managed to keep his fears from the Russian, and

continued to train him for his mission.

But the defector had his own ideas about how he

might play that game.

No matter what the CIA told him, he was going to

hedge his bets. There was obviously something wrong with the blueprints - so

he decided to mention that fact to the Iranians in his letter. They would

certainly find flaws for themselves, and if he didn't tell them first, they

would never want to deal with him again.

The Iranians clearly didn't want publicity.

An Austrian postman helped him. As the Russian

stood by, the postman opened the building door and dropped off the mail. The

Russian followed suit; he realized that he could leave his package without

actually having to talk to anyone. He slipped through the front door, and

hurriedly shoved his envelope through the inner-door slot at the Iranian

office.

He was the front man for what may have been one

of the most reckless operations in the modern history of the CIA, one that

may have helped put nuclear weapons in the hands of a charter member of what

President

George W Bush has called the "axis of

evil".

It's not clear who originally came up with the

idea, but the plan was first approved

by

Clinton. After the Russian

scientist's fateful trip to Vienna, however, the Merlin operation was

endorsed by the Bush administration, possibly with an eye toward repeating

it against North Korea or other dangerous states.

But in previous cases, such "Trojan horse" operations involved conventional weapons; none of the former officials had ever heard of the CIA attempting to conduct this kind of high-risk operation with designs for a nuclear bomb.

The former officials also said these kind of programs must be closely monitored by senior CIA managers in order to control the flow of information to the adversary. If mishandled, they could easily help an enemy accelerate its weapons development.

That may be what happened with Merlin.

Nuclear experts say that they would thus be able to extract valuable information from the blueprints while ignoring the flaws.

|