|

21 September 2016 from Nature website

better-off individuals and those educated at elite institutions such as Eton College, UK,

are often

over-represented.

poverty and social background remain huge barriers

in scientific careers.

Last year, Christina Quasney was close to giving up.

A biochemistry major at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, Quasney's background was anything but privileged. Her father runs a small car-repair shop in the tiny community of Millersville, Maryland, and she was the first person in her immediate family to attend university.

At the age of 25, she had already spent years struggling to make time both for her classes and the jobs she took to pay for them, yet was still far from finishing her degree.

Quasney's frustrations will sound familiar to millions of students around the world.

Researchers like to think that nothing matters in

science except the quality of people's work. But the reality is that

wealth and background matter a lot. Too few students from

disadvantaged backgrounds make it into science, and those who do

often find that they are ill-prepared owing to low-quality early

education.

And it's clear that the universal issue of class is far from universal in the way it plays out.

Here, we

look at eight countries around the world, and their efforts to

battle the many problems of class in science.

UNITED STATES - How

the classroom reflects class divide

Yet for students who share her struggles to make ends meet, the US higher-education system can pose one obstacle after another.

Government-supported early education is funded mainly at the state and local level, he notes, and because science courses are the most expensive per student, few schools in the relatively poor districts can afford to offer many of them.

Students from these districts

therefore end up being less prepared for university-level science

than are their wealthier peers, many of whom attended well-appointed

private schools.

The students who do get in then have to find a way to pay the increasingly steep cost of university.

Between 2003 and 2013, undergraduate tuition, fees, room and board rose by an average of 34% at state-supported institutions, and by 25% at private institutions, after adjusting for inflation. The bill at a top university can easily surpass US$60,000 per year.

Many students are

at least partly supported by their parents, and can also take

advantage of scholarships, grants and federal financial aid. Many,

like Quasney, work part time.

For those who go on

to graduate programs, tuition is usually paid for by a combination

of grants and teaching positions. But if graduate students have to

worry about repaying student loans, that can dissuade them from

continuing with their scientific training.

But for students such as Quasney,

staying in science can still be a matter of luck.

That chance encounter led Quasney to join Summers' laboratory in January, and it was a revelation. Before, she had felt that some of her professors had forgotten what it was like to be a struggling student.

Summers' lab is the exact opposite, she says.

Her experiences have helped her to understand what she can expect when she applies to graduate school and pursues a career in research.

CHINA - Low pay powers

brain drain

To combat large-scale poverty,

especially in the interior provinces, the communist government in

Beijing is trying to make education equally available to everyone.

And for those unable to come up with that sum, the country

has national scholarship programs, including tax-free loans and

free admission.

A quota system ensures that students from remote regions

such as Xinjiang and Tibet are represented at elite schools. China

even has 12 universities that are dedicated to minorities.

Children of senior government leaders and private business owners account for a disproportionate share of enrolment in the top universities. And students hesitate to take on the work-intensive career of a scientist when easier, and usually more lucrative, careers await them in business.

According to Hepeng Jia, a journalist who writes about science-policy issues in

China, this is especially true for good students from rich families.

The average across all scientific ranks is just 6,000 Yuan per month, or about one-fifth of the salary of a newly hired US faculty member.

Things are especially tough for postdoctoral researchers or junior-level researchers,

This leads many scientists to use part of their grants for personal expenses.

That forces them to

make ends meet by applying for more grants, which requires them to

get involved in many different projects and publish numerous papers,

which in turn makes it hard to maintain the quality of their work.

But China has also been able to lure some of the most prominent of these researchers back home.

Cao Kai, a researcher at the Science and Technology Talent Center of

the science ministry in Beijing, released a survey in April that

found one such returning scientist was rewarded with a stunningly

high annual salary of 800,000 Yuan.

That, he says, would

go a long way to attracting and retaining talent in science,

regardless of social background.

UNITED KINGDOM - The

paths not taken

A 2016 study found

that, unlike in law or finance, researchers from lower-income

backgrounds are paid no less than their more advantaged peers (D. Laurison

and S. Friedman -

The Class Pay Gap in Higher Professional and Managerial Occupations).

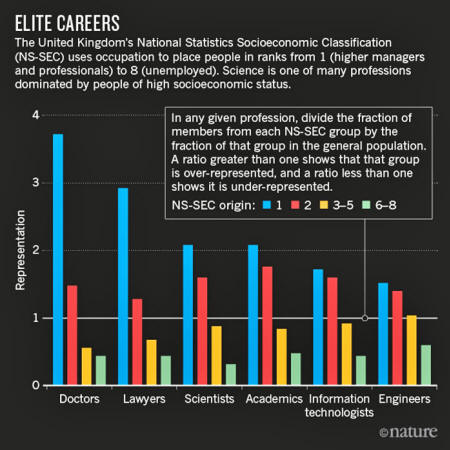

The same study found that only 15% of scientists come from working-class households, which comprise 35% of the general population (below image).

Another found that, over the past 25 years, 44% of UK-born Nobel-prizewinning scientists had gone to fee-paying schools, which educate 7% of the UK population (P. Kirby Leading People 2016 The Sutton Trust, 2016).

Laurison, D. & Friedman,

S. Am. Soc. Rev. 81, 668–695 (2016)

But those from working-class backgrounds

rarely saw it as a career - perhaps because they seldom encountered

people in science-related jobs (ASPIRES: Young People's Science and

Career Aspirations, Age 10–14 King's College London, 2013).

Early

results are promising, and the team plans to expand the program

next year.

A third issue is the effect of a sudden trebling of annual university fees to £9,000 (US$12,000) in 2012.

The danger, she adds, is that a failure to represent all backgrounds will not only squander talent, but increasingly isolate science from society.

That disconnect was apparent in the Brexit referendum in June, when more than half of the public voted to leave the European Union, compared with around one in ten researchers.

JAPAN - Deepening divisionsby David Cyranoski

Nonetheless, graduate education and academic research have become less attractive options over the past decade, especially for the underprivileged.

Some warn that this could make research a preserve of the wealthy - with grave social costs.

A big part of the problem is the rise in tuition fees: even at the relatively inexpensive national universities, the ¥86,000 (US$840) in entrance and first-year tuition fees students paid in 1975 would make little dent in the ¥817,800 they've been paying since 2005.

In addition, thanks to Japan's long economic contraction, parents are chipping in 19% less for living costs on average than they did a decade ago.

This leaves students increasingly dependent on 'scholarships' - which in Japan are mainly loans that need to be paid back.

Half of all graduate students have taken out loans, and one-quarter owe more than ¥5 million.

Even for those who make it through university on loans, jobs that would make the debt worthwhile are far from guaranteed.

In their prime years, between the ages of 30 and 60, one-third of university graduates earns less than ¥3 million per year.

The social divide in higher education already shows.

A crucial step to becoming a researcher is to enter a powerful institution such as the University of Tokyo, where the average income of a student's family is twice the national average.

The government has taken stock of the issue.

A government plan for 'investment in the future', announced on 2 August, promises to increase funding for scholarships that need not be repaid as well as to boost the availability of tax-free student loans.

But the government has yet to take up a more specific examination of the relationship between success as a researcher and economic factors, says Sumikura.

BRAZIL - Progressive policy pays offby Jeff Tollefson

The government-run schools are so bad that they are avoided by all but the poorest families. As recently as 2014, just 57% of the country's 19-year-olds had completed high school.

And yet there are signs of progress, especially in science, technology, engineering and medicine. In 2011, for example, Brazil created Science Without Borders, a program to send tens of thousands of high-achieving university and graduate students to study abroad.

Because students from wealthier families have by far the best primary and secondary education, they might have been expected to dominate the selection process.

But by the end of the first phase this year, more than half of the 73,353 participants had come from low-income families.

In São Paulo, meanwhile, the medical school at the prestigious University of Campinas (UNICAMP) gives preference to admitting gifted students from government-run schools.

The program started in 2004 after research suggested that out of those with similar test scores prior to admittance, predominantly poor government-school students tended to perform better at UNICAMP than did their counterparts from private schools.

The former comprised 68% of this year's entering class.

Carlos Henrique de Brito Cruz, who launched the UNICAMP initiative when he was the university rector, suspects that part of the answer is quite simple.

Brazil may also be seeing the fruits of the government's effort to improve scientific literacy and push more students into science careers, which gained momentum after the inauguration of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva as president in 2003.

A division at the federal Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation focuses entirely on 'social inclusion', with programs to improve public schools and promote research in fields that affect local communities, such as nutrition and sustainability.

The poor quality of secondary education remains a substantial problem that could take a generation or more to address, experts say.

Nonetheless, existing initiatives could be boosting the quality of government schools enough for ambitious students to excel, says Carlos Nobre.

The next question, he says, is whether these students will be able to bolster innovation in Brazilian science.

INDIA - Barriers of language and casteby T.V. Padma

Especially outside the cities, higher education - including science - largely remains a privilege of the rich, the politically powerful and the upper castes.

India's national census does not collect data on caste, rural or gender representation in science, nor do the country's science departments.

Nonetheless, says Gautam Desiraju, a chemist at the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore, it is clear that rural Indian students are hampered by a lack of good science teachers and lab facilities, and are unaware of opportunities to enter mainstream science (see www.nature.com/indiascience).

The barriers are even higher for rural girls, who are discouraged from pursuing higher studies or jobs, and for girls from poor urban families, who are expected to take jobs to contribute to their dowries.

Many rural students are also hampered by their poor English, the language that schools often use to explain science.

Caste - the hereditary class system of Hindu society - is officially not an issue.

India's constitution and courts have mandated that up to half of the places in education and employment must be reserved for people from historically discriminated-against classes.

However, a clause excludes several of India's top science centers from this requirement.

And in reality there is an,

Teachers do not encourage them as much as they do students from upper castes.

As a result, he says,

Still, says Desiraju, there are signs of progress.

For a long time, Indian officials assumed that all they had to do was set up centers of scientific excellence and the effects on education would simply trickle down to the masses.

At the University of Delhi South Campus, geneticist Tapasya Srivastava sees the effects of that shift.

KENYA - Easy access but poor prospectsby Linda Nordling

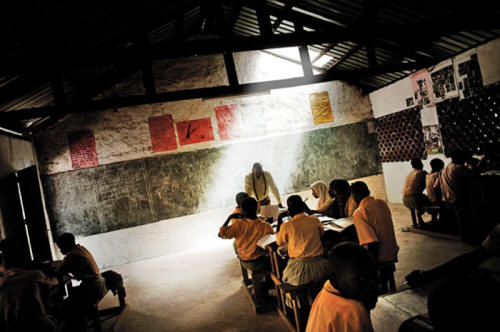

Francesco Cocco/Contrasto/eyevine Poor students from Kenya are often interested in science, but struggle to make it a career.

In Kenya, where around 40% of the population lives on less than US$1.25 a day, class matters surprisingly little for who makes it into science.

As one of Africa's fast-growing 'lion' economies, the country has seen university enrolment more than double since 2011, reaching more than 500,000 last year.

The government subsidizes tuition fees for poor secondary-school students who get good grades in science, and there are loans available to help them with living expenses.

At the postgraduate level, however, the lack of opportunities in Kenya means that many science hopefuls have to do part of their training abroad.

She now has a Rhodes scholarship to finish her PhD in chemical biology at the University of Oxford, UK.

For those staying at home, the surest path to a research career is to get a job with foreign-funded organizations such as,

But competition is fierce, and it can take years to get accepted.

This is when graduates from a poorer background are more likely to give up, says Anne Makena. They are drawn by lucrative private-sector salaries and mindful of the need to contribute financially to their families, whereas wealthier students can afford to wait.

Another source of uncertainty is Kenyan universities' struggle to secure enough operating funds from the government.

The shortfall has led vice-chancellors in the country's public universities to propose up to a five-fold rise in tuition fees for resource-intensive courses, including science. If this happens and government subsidies do not keep pace, poorer students might forego science courses for cheaper degrees.

That would be a pity, says Baldwyn Torto, head of behavioral and chemical ecology at ICIPE, because Kenyan students from modest backgrounds make excellent scientists in his experience.

RUSSIA - Positive policy, poor productivityby Quirin Schiermeier

Yet the country retained its socialist ideals in education: even now, Russia produces a large share of its science students and researchers from low- and middle-income backgrounds.

The country hosts some 3,000 universities and higher learning institutes, and about half of its secondary-school graduates go on to attend them.

The average among all Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development countries is about 35%.

In peripheral regions such as the Urals or Siberia, where local governments are keen to develop scientific and engineering capacity, teachers identify talented students as early as ages 4 to 6.

If they continue to show promise, they are encouraged to enroll at local universities, whose tuition-free programs may focus on local needs such as agricultural technology.

Children who demonstrate exceptional skills in science, art, sports or even chess may earn admission to the Sirius educational centre in Sochi on the Black Sea. This centre, backed by Russian president Vladimir Putin, was set up after the 2014 Winter Olympics to help Russia's most gifted youths develop their talent with support from leading scientists and professionals.

Since December 2015, prospective students who succeed in local or national science competitions and maths Olympiads can also hope to secure a presidential grant worth 20,000 rubles (US$307) per month.

These grants allow hundreds of students from lower social backgrounds to study at the nation's top universities on the sole condition that they will stay in Russia for at least five years after graduation.

But despite such efforts, Russia's science output remains relatively low.

One reason, Dmitry Peskov says, is the Russian science community's isolation. For all their skills and social diversity, Russian researchers tend to speak poor English and are underrepresented in international meetings and collaborations.

Uncertainty over the Russian government's future support of science adds to the problem.

|