Stretching beneath

Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay,

South America's Guaraní

Aquifer is larger than Texas and California combined.

Critics fear that the

United States is secretly taking over the underground reservoir.

But experts say the

conspiracy theorists are all wet

Conspiracy theorists fear the United States

is secretly taking control of South America's largest underground

reservoir of fresh water.

The accusations are clouding international

efforts to develop the Guaraní Aquifer. And the rumors come at a time

when water may be joining oil as one of the world's most fought-over

commodities (related:

"UN Highlights World Water Crisis"

- June 5, 2003.)

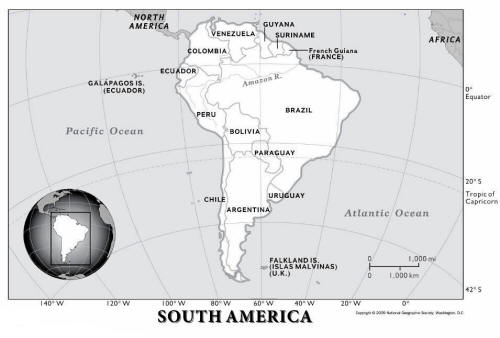

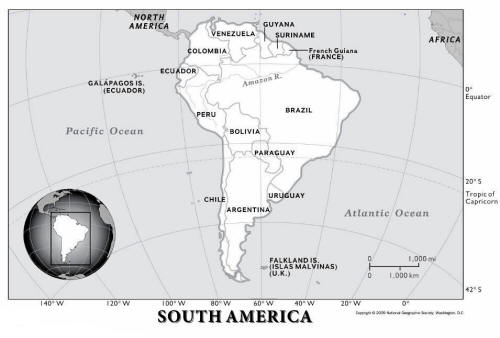

Stretching beneath parts of,

-

Argentina

-

Brazil

-

Paraguay

-

Uruguay,

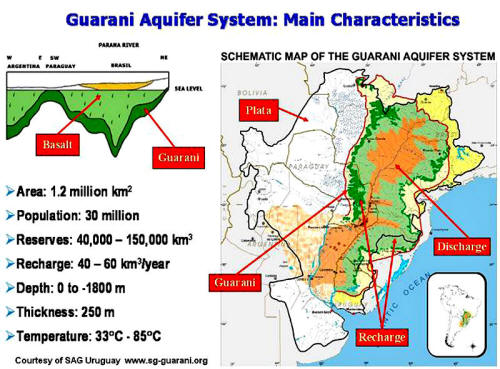

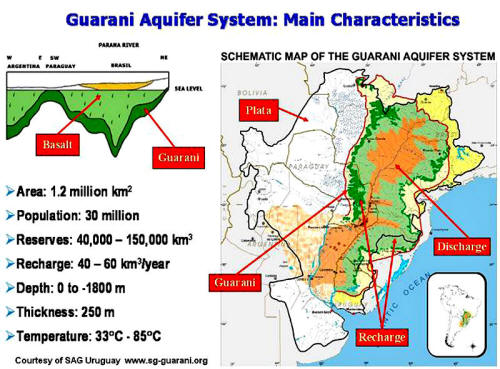

...the Guaraní Aquifer is an underground system of

water-bearing rock layers covering 460,000 square miles (1.2 million square

kilometers) - an area larger than Texas and California combined.

The International Atomic Energy Agency says the

Guaraní may be big enough to supply drinking water to 360 million people on

a sustainable basis.

Already, some 500 cities and towns across Brazil

tap the aquifer for drinking water. Officials worry that overuse and

expanding agricultural activities are threatening the reservoir's future

health.

Currently experts are studying the sandstone

aquifer's structure and devising ways to sustainably develop and manage the

cross-border resource for farming, drinking supplies, and geothermal energy.

The Global Environment Facility (GEF), a U.S.-based

funding consortium managed by

the United Nations and

the World Bank, has put

the equivalent of 13.5 million U.S. dollars into the project.

That funding plus contributions from national

governments adds up to a total of 27 million dollars for the first phase of

the Guaraní project, which began in 2003 and ends in 2009.

Distrust of the U.S.

But local distrust of U.S.-backed lending

institutions - along with the presence of U.S. troops in Paraguay - has spawned

suspicions that Washington is exerting slow control over the aquifer as

insurance against water shortages in the U.S.

"The United States already has water problems in

its southern states," said Adolfo Esquivel, an Argentine activist and Nobel

Peace Prize laureate.

"And it is clear that humans can live without oil,

gold, and diamonds but not water. The real wars will be over water, not

oil."

Esquivel points to a recent military deal, under

which U.S. Special Forces will train with Paraguayan soldiers.

He says this

is evidence of Washington's creeping control - a claim that's been further

popularized by an Argentine documentary,

Sed: Invasión Gota a Gota - Thirst: Invasion Drop by Drop

- below video:

Sed: Invasión Gota a Gota

Acuífero Guaraní

by

DANIEL CAAMAÑO

May 15, 2012

from YouTube Website

The theory centers on an ill-reputed jungle area

known as

the Triple Border, where Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay meet.

The area is home to thousands of Muslim

merchants who immigrated to South America from Syria and is known as a

hotbed of smuggling, drug dealing, and arms sales.

U.S. officials have repeatedly said that

merchants in the area launder money from illegal activities to Middle East

terrorist groups, including Hezbollah.

At an August 24, 2004, press briefing in

Washington, D.C., for example, the U.S. Treasury Department's Assistant

Secretary for Terrorist Financing, Juan Zarate, referred to a "Hezbollah

financier" imprisoned in Paraguay who Zarate said had been operating in the

Triple Border.

"He was engaged in a panoply of different

financial activities used to support Hezbollah, everything from extortion to

counterfeiting of currency to… smuggling," Zarate said.

"Really, it was a

potpourri of financial criminal activity that he was using and his

counterparts were using to support Hezbollah and to send funds back to

Lebanon."

(Read the

full

transcript of the press briefing.)

But critics say the State Department's claims

are little more than pretext for a subtle invasion.

"They have no evidence but claim a terrorist

presence in the area so they can install a military base and exert control

over the water," said Elsa Bruzzone, a policy specialist for the Buenos

Aires-based CEMIDA, a pro-democracy group founded by retired Argentine

military personnel.

Bruzzone also worries that loan conditions from

foreign lenders will force national governments to privatize the aquifer to

pay back funds.

She and other activists have pressured Mercosur

- a

regional trade bloc made up of the four countries that the aquifer

underlies, plus Venezuela - to fight any foreign control over the aquifer.

Mercosur has recently proclaimed the aquifer to

be the property of those national governments and initiated a committee to

study the issue, Bruzzone says.

Overblown?

But many in South America feel the conspiracy

theories are overblown, and U.S. officials have denied the allegations.

"The United States has no interest in the

Guaraní Aquifer, which the U.S. government recognizes as an important

resource for the inhabitants of the region," said a January statement

released by the U.S. embassy in Paraguay.

Jorge Rucks is an Argentina-based official for

the Organization of American States (OAS). The four Guaraní countries

have

elected the OAS to serve as executor of the aquifer-development project.

Rucks stresses that the four Guaraní countries

have power over the aquifer project.

He adds that the money managed by the UN and

World Bank comes without strings.

"We are talking about grants, no credits," he

said. "The money does not have to be paid back, and it carries no

conditions."

But the history of colonial domination on this

resource-rich and largely untapped continent keeps suspicions alive. Miguel Auge is a hydrology professor at the

University of Buenos Aires and was one of the first academics to initiate

studies of the aquifer.

He says South American governments and lawmakers

should be careful.

"We can't forget the invasions that Latin

American countries have suffered throughout history, because it is happening

again," he said.

"Governments here have handed the most important

patrimony we have - water, soil, oil, gas, and minerals - to foreign groups from

North America and Europe."

The Guaraní Aquifer uproar recently affected a

millionaire conservationist from the United States.

Douglas Tompkins, an ecologist and former owner

of Esprit clothing line, owns large chunks of Chile and Argentina, some of

which sit atop the aquifer. Earlier this month Argentina's populist

undersecretary of land and housing, Luis D'Elía, decided to cut chains and

padlocks at Tompkins's ranch, allowing a group of Indian activists onto the

property, located in the Esteros del Iberá wetlands in the north of

Argentina.

D'Elía has told local media he is pushing

legislation to seize Tompkins's land, in part because, D'Elía claims, the

conservationist is part of the United States' effort to "grab control of our

water."