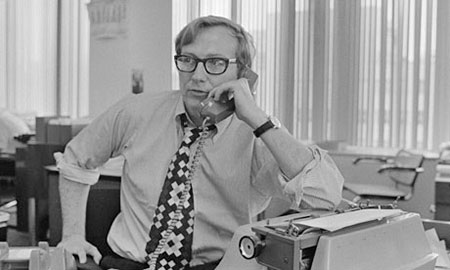

Seymour Hersh has got some extreme ideas on

how to fix journalism - close down the news bureaus of NBC and ABC, sack

90% of editors in publishing and get back to the fundamental job of

journalists which, he says, is to be an outsider.

It doesn't take much to fire up Hersh,

the

investigative journalist who has been the nemesis of US presidents since

the 1960s and who was once described by the Republican party as,

"the closest thing American journalism

has to a terrorist".

He is angry about the timidity of

journalists in America, their failure to challenge the White House and

be an unpopular messenger of truth.

Don't even get him started on the New York

Times which, he says, spends "so much more time carrying water for Obama

than I ever thought they would" - or the death of Osama bin Laden.

"Nothing's been done about that story, it's one big lie, not one word of

it is true," he says of the dramatic US Navy Seals raid in 2011 [see

footnote].

Hersh is writing a book about national

security and has devoted a chapter to the bin Laden killing.

He says a

recent report put out by an "independent" Pakistani commission about

life in the Abottabad compound in which Bin Laden was holed up would not

stand up to scrutiny.

"The Pakistanis put out a report, don't get me

going on it. Let's put it this way, it was done with considerable

American input. It's a bullshit report," he says hinting of revelations

to come in his book.

The Obama administration lies

systematically, he claims, yet none of the leviathans of American media,

the TV networks or big print titles, challenge him.

"It's pathetic, they are more than

obsequious, they are afraid to pick on this guy [Obama]," he declares in

an interview with the Guardian.

"It used to be when you were in a situation

when something very dramatic happened, the president and the minions

around the president had control of the narrative, you would pretty much

know they would do the best they could to tell the story straight.

Now

that doesn't happen any more. Now they take advantage of something like

that and they work out how to re-elect the president."

He isn't even sure if the recent revelations

about the depth and breadth of surveillance by the National Security

Agency will have a lasting effect.

Snowden changed the debate

on surveillance

He is certain

that NSA whistleblower

Edward Snowden,

Hersh says he

and other journalists had written about surveillance, but Snowden was

significant because he provided documentary evidence - although he is

skeptical about whether the revelations will change the US government's

policy.

"Duncan Campbell [the British

investigative journalist who broke the Zircon cover-up story], James

Bamford [US journalist] and Julian Assange and me and the New

Yorker, we've all written the notion there's constant surveillance,

but he [Snowden] produced a document and that changed the whole

nature of the debate, it's real now," Hersh says.

"Editors love documents. Chicken-shit

editors who wouldn't touch stories like that, they love documents,

so he changed the whole ball game," he adds, before qualifying his

remarks.

"But I don't know if it's going to mean

anything in the long [run] because the polls I see in America - the

president can still say to voters 'al-Qaida, al-Qaida' and the

public will vote two to one for this kind of surveillance, which is

so idiotic," he says.

Holding court to a packed audience at City

University in London's summer school on

investigative journalism, 76-year-old Hersh is on full throttle, a

whirlwind of amazing stories of how journalism used to be:

-

how he exposed the My Lai massacre

in Vietnam

-

how he got the Abu Ghraib pictures

of American soldiers brutalizing Iraqi prisoners

-

what he thinks of Edward Snowden

Hope of redemption

Despite his concern about the timidity of

journalism he believes the trade still offers hope of redemption.

"I have this sort of heuristic view that

journalism, we possibly offer hope because the world is clearly run

by total nincompoops more than ever… Not that journalism is always

wonderful, it's not, but at least we offer some way out, some

integrity."

His story of how he uncovered

the My Lai

atrocity is one of old-fashioned shoe-leather journalism and doggedness.

Back in 1969, he got a tip about a

26-year-old platoon leader, William Calley, who had been charged

by the army with alleged mass murder.

Instead of picking up the phone to a press

officer, he got into his car and started looking for him in the army

camp of Fort Benning in Georgia, where he heard he had been detained.

From door to door he searched the vast

compound, sometimes blagging his way, marching up to the reception,

slamming his fist on the table and shouting:

"Sergeant, I want Calley out now."

Eventually his efforts paid off

with

his first story appearing in the St Louis Post-Despatch, which was

then syndicated across America and eventually earned him the

Pulitzer Prize.

"I did five stories. I charged $100 for

the first, by the end the [London] Times were paying $5,000."

He was hired by the New York Times to follow

up the Watergate scandal and ended up hounding Nixon over Cambodia.

Almost 30 years later, Hersh made global

headlines all over again with his exposure of the

abuse of Iraqi

prisoners at Abu Ghraib.

Put in the hours

For students of journalism his message is

put the miles and the hours in.

He knew about Abu Ghraib five months before

he could write about it, having been tipped off by a senior Iraqi army

officer who risked his own life by coming out of Baghdad to Damascus to

tell him how prisoners had been writing to their families asking them to

come and kill them because they had been "despoiled".

"I went five months looking for a document,

because without a document, there's nothing there, it doesn't go

anywhere."

Hersh returns to US president

Barack Obama.

He has said before that the confidence of the US press

to challenge the US government collapsed post 9/11, but he is adamant

that Obama is worse than Bush.

"Do you think Obama's been judged by any

rational standards? Has Guantanamo closed? Is a war over? Is anyone

paying any attention to Iraq? Is he seriously talking about going

into Syria?

We are not doing so well in the 80 wars

we are in right now, what the hell does he want to go into another

one for. What's going on [with journalists]?" he asks.

He says investigative journalism in the US

is being killed by the crisis of confidence, lack of resources and a

misguided notion of what the job entails.

"Too much of it seems to me is looking

for prizes. It's journalism looking for the Pulitzer Prize," he

adds.

"It's a packaged journalism, so you pick

a target like - I don't mean to diminish because anyone who does it

works hard - but are railway crossings safe and stuff like that,

that's a serious issue but there are other issues too.

"Like killing people, how does [Obama]

get away with the drone program,

-

Why aren't we doing more?

-

How does he justify it?

-

What's the intelligence?

-

Why don't we find out how good

or bad this policy is?

-

Why do

newspapers constantly cite the two or three groups that

monitor drone killing?

-

Why don't we do our own work?

"Our job is to find out ourselves, our

job is not just to say - here's a debate' our job is to go beyond

the debate and find out who's right and who's wrong about issues.

That doesn't happen enough. It costs money, it costs time, it

jeopardizes, it raises risks.

There are some people - the New York

Times still has investigative journalists but they do much more of

carrying water for the president than I ever thought they would…

it's like you don't dare be an outsider any more."

He says in some ways President

George Bush's administration was easier to write about.

"The Bush era, I felt it was much easier

to be critical than it is [of] Obama. Much more difficult in the

Obama era," he said.

Asked what the solution is Hersh warms to

his theme that most editors are pusillanimous and should be fired.

"I'll tell you the solution, get rid of

90% of the editors that now exist and start promoting editors that

you can't control," he says.

I saw it in the New York Times, I see people

who get promoted are the ones on the desk who are more amenable to the

publisher and what the senior editors want and the trouble makers don't

get promoted.

Start promoting better people who look you

in the eye and say 'I don't care what you say'. Nor does he understand

why the Washington Post held back on the Snowden files until it learned

the Guardian was about to publish.

If Hersh was in charge of US Media Inc, his

scorched earth policy wouldn't stop with newspapers.

"I would close down the news bureaus of

the networks and let's start all over, tabula rasa. The majors, NBCs,

ABCs, they won't like this - just do something different, do

something that gets people mad at you, that's what we're supposed to

be doing," he says.

Hersh is currently on a break from

reporting, working on a book which undoubtedly will make for

uncomfortable reading for both Bush and Obama.

"The republic's in trouble, we lie about

everything, lying has become the staple."

And he implores journalists to do something

about it.

Footnote

This article was amended on 1 October 2013.

The original text stated that Hersh sold a

story about the My Lai massacre to the New York Times for $5,000 when in

fact it was the Times of London. Hersh has pointed out that he was in no

way suggesting that Osama bin Laden was not killed in Pakistan, as

reported, upon the president's authority: he was saying that it was in

the aftermath that the lying began.

Finally, the interview took place in the

month of July, 2013.