August 30, 2011

from

WBEZ91.5

Website

A K-9 police officer and his

partner, "Bart,"

patrol New York's Grand

Central Terminal in 2003.

Less visible are the

clandestine security measures

the government has

implemented since 2001.

Thousands of government organizations and private companies work on programs

related to counterterrorism, homeland security and intelligence.

Last December, The Washington Post

reported that

this,

"top-secret world... has become so large, so unwieldy and so secretive

that no one knows how much money it costs, how many people it employs, how

many programs exist within it or exactly how many agencies do the same

work."

On today's Fresh Air, Washington Post national security reporter

Dana

Priest, the co-author of both the Post's investigative series and the book

Top Secret America: The Rise of the New American Security State,

joins Terry Gross for a discussion about how the "terrorism industrial

complex" created in response to the Sept. 11 attacks grew to be so big.

"The government said, 'We're facing an enemy we don't understand, we

don't have the tools to deal with it, here's billions... of dollars and

a blank check after that for anybody with a good idea to go and pursue

it' " she says.

"Not only does the government find it

difficult to get its arms around itself, [but now] it doesn't know

what's inside, it doesn't know what works, it doesn't know what doesn't

work. And nobody still, 10 years later, is really in charge of those

questions."

Priest and fellow Post reporter William Arkin

found that many security and intelligence agencies do the same work.

For example, there are 51 federal organizations

and military commands, she says, that track the flow of money to and from

terrorist networks.

"So what you have are good-hearted people

and companies and employees who are doing what they think they can get

paid for and what might help but so much of it is reinventing the wheel

that another organization has already reinvented five times," she says.

Because much of the counterterrorism work is

classified, she says, there's no room for the public to have any kind of

oversight into the process.

That role falls largely those with security

clearances and the intelligence committees within Congress.

"So you and I cannot pressure government to

do better," she says.

"The interest groups that weigh in on every

other subject matter in our governments cannot weigh in, in any public

manner. So you get this cabal of people who have clearances and they

weigh in - and that cabal, unfortunately, includes a profit motive

because there are so many companies whose livelihoods depend on a

continued flow of money to them - because [right after

Sept. 11] the

government relied on contractors to do the work ... [because] Congress

and the White House didn't want it to appear like they were growing

government while they were asking the government to do much more."

Many of the contractors that the government hired to do counterintelligence

and security work are paid much more than their public counterparts in the

CIA and Homeland Security.

"[The government] is willing to pay these

companies money to get the bodies," she says.

"It's created this unintended adverse

consequence: [The private companies then] also drew from the agencies.

It sucked away the very people that those agencies needed to keep. And

it did it because it could attract them with relatively high salaries

and less stressful work than when you're working in government.

So in

addition to costing more, it cost the government some of its best people

- and then it sold those people back to them at two or three times as

much money."

More than 800,000 people now hold top-secret

security clearances.

And now an entire industry has sprung up to

provide those clearances, says Priest.

"The government is now contracting

contractors to do the security clearances for other contractors," she

says.

"The contractors, in the beginning, were

just supposed to be supplemental to the federal employees... But now,

they are everywhere. And some agencies... could not exist without them."

JSOC

When 9/11 came along, not only were more

things put into the secret box, but they were more highly classified

- making it difficult for not only the public to understand, but for

other people within government [to understand].

- Dana Priest

Priest also profiles the Joint Special

Operations Command, or

JSOC, the clandestine military command that now

conducts more anti-terrorism operations than the CIA.

The organization, established in 1980, conducted

hostage rescues for many years. It has since developed into a highly

secretive and lethal force responsible for reconnaissance and targeted

military operations - including the one last May in Pakistan that found and

killed Osama Bin Laden.

Priest describes JSOC as,

"sitting at the center of a secret universe

as the dark matter that shapes the world in ways that are usually not

detectable."

"In the last 10 years, JSOC has managed to pull off a level of obscurity

that the CIA hasn't even managed," she says.

"Until now, we have had sporadic reporting

here and there about actions undertaken by JSOC but [we have] tried to

put together its history since 9/11 when it was completely revamped into

a manhunting, lethal arm of the military."

Priest and Arkin looked at what JSOC has been

allowed to do and how effective the organization has been in the past

decade.

"As a killing machine, it is highly

effective," she says.

"No one competes with them. It is a

professionalized killing force and that's what it's been used for. They

operate in very small groups of people so they can keep a low profile.

They have their own interrogation facilities that they alone control.

And they have captured and killed a lot more Al-Qaeda than the CIA

have."

The JSOC team also did reconnaissance and

special-operations work in the months directly after Sept. 11.

Dana Priest received the 2008 Pulitzer Prize

for her coverage of the Water

Reed Army Medical Center

and the 2006 Pulitzer Prize

for her work on CIA secret prisons.

Whitney Shefte/Little, Brown & Co.

Dana Priest received the 2008 Pulitzer Prize for

her coverage of the Water Reed Army Medical Center and the 2006 Pulitzer

Prize for her work on CIA secret prisons.

"They also have a kill list," she says.

"That is one of the more controversial

aspects of JSOC and the CIA - they can put people on that list and they

can then hunt them down and kill them. Some people call that

assassination, which is banned in the United States. Other people call

that targeted killing. That's what the U.S. government calls it."

Priest says both Presidents

Bush and

Obama have

used JSOC as a personal weapon against terrorists.

"In JSOC's case, they have the authority to

do more killing in this way than the CIA does without informing

Congress," she says.

"Under [President] Bush, they did not inform

Congress much at all about JSOC's actions. President Obama has taken a

slightly different approach. He believes they should brief Congress...

The CIA has more oversight of its activities

than JSOC does. JSOC's oversight comes from its own chain of command.

The CIA's oversight comes not only from its own chain of command - but

also from Congress."

Priest says there's a difference between secrecy

- and the current state of secrecy that was created in response to the

terrorist attacks on Sept. 11.

"We're not arguing that secrecy is

unnecessary - not at all," she says.

"The bin Laden strike is one great example

of why you do have to keep operations secret. However, the secrecy has

gotten out of control. Everybody in government and outside has made that

point. When 9/11 came along, not only were more things put into the

secret box, but they were more highly classified - making it difficult

for not only the public to understand, but for other people within

government [to understand]...

And now, it's simply out of control. And

most people I interviewed would agree with that. And they would also

agree that the government can no longer maintain its secrets."

Interview Highlights

On the intelligence committees in Congress:

"But the intelligence committees are so

understaffed and overwhelmed by the largeness of the task.

There are literally only one handful of

staffers who have any expertise in the National Reconnaissance

Office, which is the office that manages spy satellites and happens

to spend tens of billions of dollars a year to do that.

It's a critical function. Those handful

of staffers - half of them are very inexperienced - because there's

a relatively high turnover. That's your oversight."

On why she wanted to report on this:

"Watching social programs overseas that

are meant to deal with terrorism in a different way - not in a

military way - be killed because of funding or be underappreciated

because they couldn't show results on paper quickly, while there was

so much waste in this area."

On the secrecy surrounding JSOC:

"It's all shrouded in secrecy and in

this case, a level of secrecy that's beyond all others so it's hard

for the public to know not only what they're doing but whether those

actions are effective or whether they're counterproductive...

Whatever they do - and if they make

mistakes - there is always a cleanup operation afterwards. There are

always people in a village who hate what is being done and civilians

are killed and that has happened repeatedly.

The blowback for such

secret operations is no longer secret...

That is one of the downsides to being

able to give the authority to one person or a group of people to use

such a lethal weapon without the rest of the world knowing - because

you're operating in the dark, by yourself, without the oversight you

normally get."

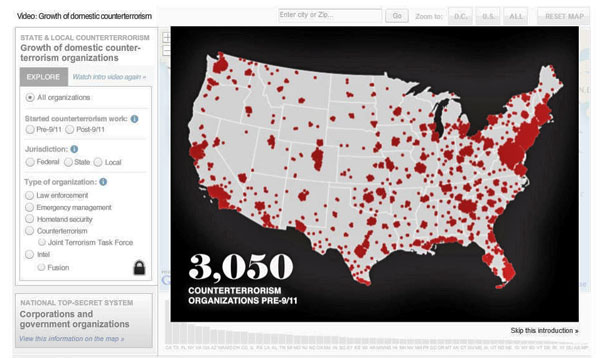

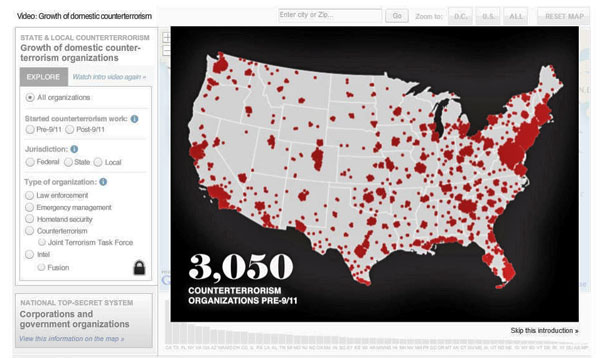

Where is Top Secret America?

for Multimedia, click above

image

Video

Top Secret America