|

by Alfred W. McCoy December 5, 2010 from AlterNet Website

A soft landing for America 40 years from now? Don’t bet on it.

The demise of the United States as the global

superpower could come far more quickly than anyone imagines. If Washington

is dreaming of 2040 or 2050 as the end of the American Century, a more

realistic assessment of domestic and global trends suggests that in 2025,

just 15 years from now, it could all be over except for the shouting.

So delicate is their ecology of power that, when things start to go truly bad, empires regularly unravel with unholy speed:

Future historians are likely to identify the Bush administration’s rash invasion of Iraq in that year as the start of America's downfall.

However, instead of the bloodshed that marked

the end of so many past empires, with cities burning and civilians

slaughtered, this twenty-first century imperial collapse could come

relatively quietly through the invisible tendrils of economic collapse or

cyberwarfare.

As a half-dozen European nations have discovered, imperial decline tends to have a remarkably demoralizing impact on a society, regularly bringing at least a generation of economic privation.

As the economy cools, political temperatures rise, often sparking

serious domestic unrest.

In one of its periodic futuristic reports, Global Trends 2025, the Council cited,

Like many in Washington, however, the Council’s analysts anticipated a very long, very soft landing for American global preeminence, and harbored the hope that somehow the U.S. would long,

No such luck.

Under current projections, the United States

will find itself in second place behind China (already the world's second

largest economy) in economic output around 2026, and behind India by 2050.

Similarly, Chinese innovation is on a trajectory toward world leadership in

applied science and military technology sometime between 2020 and 2030, just

as America's current supply of brilliant scientists and engineers retires,

without adequate replacement by an ill-educated younger generation.

By that year, however, China's global network of

communications satellites, backed by the world's most powerful

supercomputers, will also be fully operational, providing Beijing with an

independent platform for the weaponization of space and a powerful

communications system for missile- or cyber-strikes into every quadrant of

the globe.

In his State of the Union address last January, President Obama offered the reassurance that,

A few days later, Vice President Biden ridiculed the very idea that,

Similarly, writing in the November issue of the

establishment journal

Foreign Affairs, neo-liberal foreign policy

guru Joseph Nye waved away talk of China's economic and military

rise, dismissing “misleading metaphors of organic decline” and denying that

any deterioration in U.S. global power was underway.

Already, Australia and Turkey, traditional U.S. military allies, are using their American-manufactured weapons for joint air and naval maneuvers with China. Already, America's closest economic partners are backing away from Washington's opposition to China's rigged currency rates.

As the president flew back from his Asian tour last month, a gloomy New York Times headline summed the moment up this way:

Viewed historically, the question is not whether the United States will lose its unchallenged global power, but just how precipitous and wrenching the decline will be.

In place of Washington's wishful thinking, let’s use the National Intelligence Council's own futuristic methodology to suggest four realistic scenarios for how, whether with a bang or a whimper, U.S. global power could reach its end in the 2020s (along with four accompanying assessments of just where we are today). The future scenarios include: economic decline, oil shock, military misadventure, and World War III.

While these are hardly the only possibilities

when it comes to American decline or even collapse, they offer a window into

an onrushing future.

A harbinger of further decline:

Add to this clear evidence that the U.S. education system, that source of future scientists and innovators, has been falling behind its competitors.

After leading the world for decades in 25- to 34-year-olds with university degrees, the country sank to 12th place in 2010. The World Economic Forum ranked the United States at a mediocre 52nd among 139 nations in the quality of its university math and science instruction in 2010. Nearly half of all graduate students in the sciences in the U.S. are now foreigners, most of whom will be heading home, not staying here as once would have happened.

By 2025, in other words, the United States is

likely to face a critical shortage of talented scientists.

In mid-2009, with the world's central banks

holding an astronomical $4 trillion in U.S. Treasury notes, Russian

president Dimitri Medvedev

insisted that it was time to end “the

artificially maintained unipolar system” based on “one formerly strong

reserve currency.”

Take these as signposts of a world to come, and of a possible attempt, as economist Michael Hudson has argued,

Suddenly, the cost of imports soars. Unable to

pay for swelling deficits by selling now-devalued Treasury notes abroad,

Washington is finally forced to slash its bloated military budget. Under

pressure at home and abroad, Washington slowly pulls U.S. forces back from

hundreds of overseas bases to a continental perimeter. By now, however, it

is far too late.

Meanwhile, amid soaring prices, ever-rising unemployment, and a continuing decline in real wages, domestic divisions widen into violent clashes and divisive debates, often over remarkably irrelevant issues. Riding a political tide of disillusionment and despair, a far-right patriot captures the presidency with thundering rhetoric, demanding respect for American authority and threatening military retaliation or economic reprisal.

The world pays next to no attention as the

American Century ends in silence.

Speeding by America's gas-guzzling economy in the passing lane, China became the world's number one energy consumer this summer, a position the U.S. had held for over a century.

Energy specialist Michael Klare has argued that this change means China will,

By 2025, Iran and Russia will control almost half of the world's natural gas supply, which will potentially give them enormous leverage over energy-starved Europe.

Add petroleum reserves to the mix and, as the

National Intelligence Council has

warned, in just 15 years two countries,

Russia and Iran, could “emerge as energy kingpins.”

The real lesson of the Deepwater Horizon oil disaster in the Gulf of Mexico was not BP's sloppy safety standards, but the simple fact everyone saw on “spillcam”:

Compounding the problem, the Chinese and Indians have suddenly become far heavier energy consumers.

Even if fossil fuel supplies were to remain constant (which they won’t), demand, and so costs, are almost certain to rise - and sharply at that. Other developed nations are meeting this threat aggressively by plunging into experimental programs to develop alternative energy sources. The United States has taken a different path, doing far too little to develop alternative sources while, in the last three decades, doubling its dependence on foreign oil imports.

Between 1973 and 2007, oil imports have

risen from 36% of energy consumed in the

U.S.

to 66%.

By comparison, it makes the 1973 oil shock (when prices quadrupled in just months) look like the proverbial molehill. Angered at the dollar's plummeting value, OPEC oil ministers, meeting in Riyadh, demand future energy payments in a “basket” of Yen, Yuan, and Euros. That only hikes the cost of U.S. oil imports further.

At the same moment, while signing a new series

of long-term delivery contracts with China, the Saudis stabilize their own

foreign exchange reserves by switching to the Yuan. Meanwhile, China pours

countless billions into building a massive trans-Asia pipeline and funding

Iran's exploitation of the world largest natural gas field at South Pars in

the Persian Gulf.

Under heavy economic pressure, London agrees to

cancel the U.S. lease on its Indian Ocean island base of Diego Garcia, while

Canberra, pressured by the Chinese, informs Washington that the Seventh

Fleet is no longer welcome to use Fremantle as a homeport, effectively

evicting the U.S. Navy from the Indian Ocean.

At this point, the U.S. can still cover only an

insignificant 12% of its energy needs from

its nascent alternative energy industry, and remains dependent on imported

oil for half of its energy consumption.

With

thermostats dropping, gas prices climbing

through the roof, and dollars flowing overseas in return for costly oil, the

American economy is paralyzed. With long-fraying alliances at an end and

fiscal pressures mounting, U.S. military forces finally begin a staged

withdrawal from their overseas bases.

This phenomenon is known among historians of

empire as “micro-militarism” and seems to involve psychologically

compensatory efforts to salve the sting of retreat or defeat by occupying

new territories, however briefly and catastrophically. These operations,

irrational even from an imperial point of view, often yield hemorrhaging

expenditures or humiliating defeats that only accelerate the loss of power.

With the hubris that marks empires over the

millennia, Washington has increased its troops in Afghanistan to 100,000,

expanded the war into Pakistan, and

extended its commitment to 2014 and beyond,

courting disasters large and small in this guerilla-infested, nuclear-armed

graveyard of empires.

With the U.S. military

stretched thin from Somalia to the Philippines and tensions rising in

Israel, Iran, and Korea, possible combinations for a disastrous military

crisis abroad are multifold.

Heavy loses are taken and in retaliation, an

embarrassed American war commander looses B-1 bombers and F-16 fighters to

demolish whole neighborhoods of the city that are believed to be under

Taliban control, while AC-130U “Spooky” gunships rake the rubble with

devastating cannon fire.

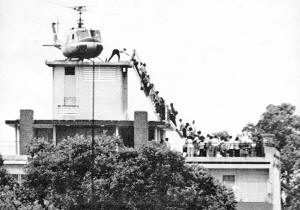

In scenes reminiscent of Saigon in 1975 (below images), U.S. helicopters rescue American soldiers and civilians from rooftops in Kabul and Kandahar.

Meanwhile, angry at the endless, decades-long stalemate over Palestine, OPEC’s leaders impose a new oil embargo on the U.S. to protest its backing of Israel as well as the killing of untold numbers of Muslim civilians in its ongoing wars across the Greater Middle East.

With gas prices soaring and refineries running dry, Washington makes its move, sending in Special Operations forces to seize oil ports in the Persian Gulf. This, in turn, sparks a rash of suicide attacks and the sabotage of pipelines and oil wells.

As black clouds billow skyward and diplomats

rise at the U.N. to bitterly denounce American actions, commentators

worldwide reach back into history to brand this “America's Suez,” a telling

reference to the 1956 debacle that marked the end of the British Empire.

Even a year earlier no one would have predicted

such a development. As Washington played upon its alliance with London to

appropriate much of Britain's global power after World War II, so China is

now using the profits from its export trade with the U.S. to fund what is

likely to become a military challenge to American dominion over the

waterways of Asia and the Pacific.

In August, after Washington expressed a “national interest” in the South China Sea and conducted naval exercises there to reinforce that claim, Beijing's official Global Times responded angrily, saying,

Amid growing tensions, the Pentagon reported that Beijing now holds,

By developing “offensive nuclear, space, and cyber warfare capabilities,” China seems determined to vie for dominance of what the Pentagon calls,

With ongoing development of the powerful Long

March V booster rocket, as well as the

launch of two satellites in January 2010

and

another in July, for a total of five,

Beijing signaled that the country was making rapid strides toward an

“independent” network of 35 satellites for global positioning,

communications, and reconnaissance capabilities by 2020.

Military planners expect this integrated system to envelop the Earth in a cyber-grid capable of blinding entire armies on the battlefield or taking out a single terrorist in field or favela.

By 2020, if all goes according to plan, the

Pentagon will launch a three-tiered shield of space drones - reaching from

stratosphere to exosphere, armed with agile missiles, linked by a resilient

modular satellite system, and operated through total telescopic

surveillance.

The

X-37B is the first in a new generation of

unmanned vehicles that will mark the full weaponization of space, creating

an arena for future warfare unlike anything that has gone before.

If we simply employ the sort of scenarios that

the Air Force itself

used in its 2009 Future Capabilities Game,

however, we can gain “a better understanding of how air, space and

cyberspace overlap in warfare,” and so begin to imagine how the next world

war might actually be fought.

Thousands of miles away at the U.S.

CyberCommand's

operations center in Texas, cyberwarriors

soon detect malicious binaries that, though fired anonymously, show the

distinctive digital fingerprints of China's

People's Liberation Army.

It suddenly fires all the rocket pods beneath

its enormous 400-foot wingspan, sending dozens of lethal missiles plunging

harmlessly into the Yellow Sea, effectively disarming this formidable

weapon.

Zero response. In near panic, the Air Force

launches its

Falcon Hypersonic Cruise Vehicle into an

arc 100 miles above the Pacific Ocean and then, just 20 minutes later, sends

the computer codes to fire missiles at seven Chinese satellites in nearby

orbits. The launch codes are suddenly inoperative.

Carrier fleets begin steaming in circles in the mid-Pacific. Fighter squadrons are grounded. Reaper drones fly aimlessly toward the horizon, crashing when their fuel is exhausted. Suddenly, the United States loses what the U.S. Air Force has long called “the ultimate high ground”: space.

Within hours, the military power that had

dominated the globe for nearly a century has been defeated in World War III

without a single human casualty.

As happened to European empires after World War

II, such negative forces will undoubtedly prove synergistic. They will

combine in thoroughly unexpected ways, create crises for which Americans are

remarkably unprepared, and threaten to spin the economy into a sudden

downward spiral, consigning this country to a generation or more of economic

misery.

Yet both China and Russia evince self-referential cultures, recondite non-roman scripts, regional defense strategies, and underdeveloped legal systems, denying them key instruments for global dominion.

At the moment then, no single superpower seems

to be on the horizon likely to succeed the U.S.

He argues that the billion people already packed into fetid favela-style slums worldwide (rising to two billion by 2030) will make,

As darkness settles over some future super-favela,

At a midpoint on the spectrum of possible

futures, a new global oligopoly might emerge between 2020 and 2040, with

rising powers

China, Russia, India, and Brazil collaborating with receding

powers like Britain, Germany, Japan, and the United States to enforce an ad

hoc global dominion, akin to the loose alliance of European empires that

ruled half of humanity circa 1900.

In this neo-Westphalian world order, with its endless vistas of micro-violence and unchecked exploitation, each hegemon would dominate its immediate region - Brasilia in South America, Washington in North America, Pretoria in southern Africa, and so on.

Space, cyberspace, and the maritime deeps,

removed from the control of the former planetary “policeman,” the United

States, might even become a new global commons, controlled through an

expanded U.N. Security Council or some ad hoc body.

Congress and the president are now in gridlock;

the American system is flooded with corporate money meant to jam up the

works; and there is little suggestion that any issues of significance,

including our wars, our bloated national security state, our starved

education system, and our antiquated energy supplies, will be addressed with

sufficient seriousness to assure the sort of soft landing that might

maximize our country's role and prosperity in a changing world.

It seems increasingly doubtful that the United States will have anything like Britain's success in shaping a succeeding world order that protects its interests, preserves its prosperity, and bears the imprint of its best values.

|