|

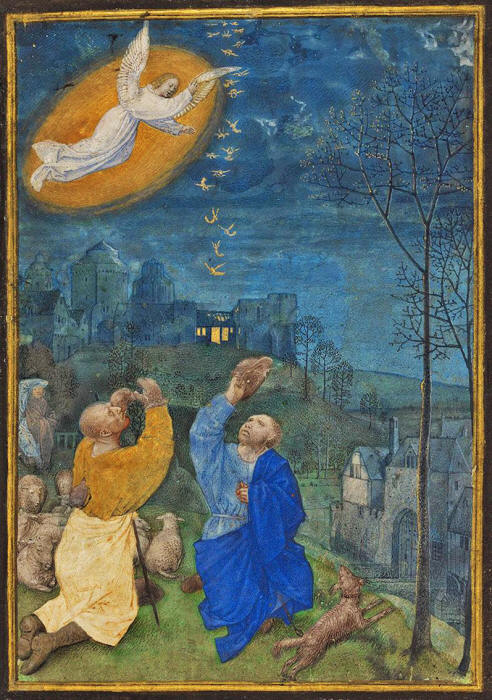

by Rebekah Wallace The Annunciation to the Shepherds (c1476-80, Flemish) by the Master of the Houghton Miniatures.

Courtesy the

Getty Museum, Los Angeles sought to understand the nature of angels, they unwittingly laid the foundations of modern physics

The answer, according to the 12th-century philosopher and theologian Maimonides, was simple.

Quoting a famous rabbi who talked about 'the angel put in charge of lust', Maimonides commented that,

Before the discovery of gravity, energy or magnetism, it was unclear why the cosmos behaved in the way it did, and angels were one way of accounting for the movement of physical entities.

Maimonides argued that,

Medieval painting of an angel appearing to shepherds at night,

featuring a

glowing sky and a pastoral landscape. (c1476-80, Flemish) by the Master of the Houghton Miniatures. Courtesy the Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Even when belief in angels later dissipated, modern physicists continued to posit incorporeal intelligences to help explain the inexplicable.

Malevolent angelic forces (i.e., demons) have appeared in compelling thought experiments across the history of physics.

These well-known 'demons of physics' served as useful placeholders, helping physicists find scientific explanations for only vaguely imagined solutions.

You can still find them in textbooks today. But that's not the most important legacy of medieval angelology.

Angels also catalyzed ferociously precise debates about the nature of place, bodies and motion, which would inspire something like a modern conceptual toolbox for physicists, honing concepts such as space and dimension.

Angels have been around at least since Biblical times, and are described in various, and sometimes odd, ways.

In the Book of Ezekiel, for example, the Cherubim have intersecting wheels sparkling like topaz that move them in all four directions without turning, and their,

However, aside from these googly-eyed angels, angels were also, as we can see from Maimonides, a way of explaining movement in the world.

They were spiritual substances that could take on

the appearance of corporeal beings, but also acted as invisible,

intelligent, immaterial forces.

The precise nature or essence of angels became a serious cause for debate, and these debates were not mere thought experiments.

Rather, because of the real belief in the existence of angels, theologians and philosophers could think through angels as a way of understanding the nature of the physical world and things like place, bodies and motion.

This was motivated by significant theological concerns.

One concern was that,

For us, our bodies are what make us limited, able to exercise force only directly, such as when I throw a ball.

This was dangerous territory for theologians,

potentially challenging God's omnipresence and omnipotence.

It was not a fringe topic, saved for pedants and scholars, but of serious importance in the debates that determined the limits and relations of physics, philosophy and theology.

Angelology and its synthesis with the

physics of its day would prime later thinkers to reflect on the

nature of bodies, place and movement, but also, importantly, how

they might relate to each other.

How the Greek philosopher conceived of place,

motion and bodies profoundly shaped the medieval worldview. And some

of the most prominent theologians of the day, such as Aquinas, used

Aristotle to think about the nature of angelic location.

That's why fire licks the air and a

rock falls.

As the philosopher Tiziana Suárez-Nani points out in Angels, Space and Place (2008),

For Aristotle, bodies could not exist without place, which served as a kind of container.

In other words, a vacuum is not possible in

Aristotle's view.

This nature makes them move in a certain direction, so place too must be inherently directional.

We now understand that direction within space is relative only to a starting reference point; the Universe as we know it has no absolute 'up' or 'down'.

But in the Aristotelian worldview,

In sum, Aristotle's physics linked bodies, place

and movement, and each depended upon the other.

that an angel has a different type of location

than a bodily being...

If you recall, theological concerns at the time required angels to have a specific location - to be limited and bodiless - in order to avoid angels with limitless power, rendering them omnipotent as well as omnipresent.

Since Aristotle's physics was the reigning

physics of the day, medieval scholars worked to explain these

location problems within his framework.

Aquinas and others solved this problem creatively, locating angels not by their physical dimensionality but by their operations. Aquinas proposed that an angel has a different type of location than a bodily being.

An angel is in a place by virtue of applying its

power to the physical objects in a given place. This limited both an

angel's operations and their location, locating them by their

operations, rather than by a body.

So when the nature of angels became a kind of

playground for thinking about the nature of the world, it was an

especially fraught subject.

These theses covered various philosophical and theological positions, but an impressive 28 of the 219 had to do with angels also known as 'separate substances' or 'intelligences'.

Some of these had to do with the nature of angel location and operation.

Importantly, the Condemnations of 1277 forbade believing that angels are located by their operations rather than by their substance, so Aquinas' solution for angelic location was now off the table.

This constraint would require even more creative

maneuvering from scholars.

His angelology would redefine the concept of

place that was so central to Aristotelian and medieval physics and,

as Helen Lang notes in Aristotle's Physics and its

Medieval Varieties (1992), this would shift the contours of

physics forever.

Painting of a person in a brown robe and hat gesturing with hands, seated by a book on a ledge

with a green

backdrop. (c1476-8) by Justus van Gent. Courtesy Wikimedia

But the Condemnations of 1277 explicitly forbade Aquinas' explanation: that angels are in a place according to their operations.

The challenge for medieval thinkers was to find a

way of locating an angel by its essence, without it being a bodily

substance, and to locate their operations, but without those

operations being the sole factor 'locating' the angels.

He did this to solve the theological problem of

God being able to create a rock outside of place, something

theologians claimed God could do, but his solution applied

equally to angelic location. In doing so, his creative rethinking of

physics would lead to new concepts and reconceptualise old ones,

shaping modern physics in a quite radical way.

When thought about in terms of dimension, the 'place' occupied by an object stays the same as the object moves through locations.

In this sense, its 'place', redefined as dimension, is the same, even though it changes location. In other words, Scotus, as aptly stated by Lang, 'neutralizes' place radically.

On the Aristotelian account, direction or location were part of the definition of 'place'. When redefined more mathematically as a kind of dimension, direction is no longer a necessary feature of this new kind of 'place'.

You can have an idea much more like that of

'space', something that doesn't inherently contain 'up', 'down',

'left' or 'right' in its definition.

because they have no dimensions, can exist only in a determined place

in an undetermined way...

Whereas Aristotle had defined place as a necessary defining feature of physical bodies, Scotus did not.

Instead, he created a hybrid account in which

something can exist inside the outermost rim of the celestial sphere

(occupying place in the Aristotelian sense), but it doesn't have to;

it could equally just occupy space by having dimension outside of

that sphere.

For Scotus, Aristotle's place could exist, but it didn't define bodies.

If something did exist in Aristotelian 'place',

it was by God's will, and because of what Scotus calls a

passive power, which simply means that it is able to exist in a

place without it going against the object's nature.

Scotus argues that angels too possess the passive power to exist in a place by God's will, because in this new physics, place and body are no longer mutually defining.

But unlike physical bodies, which must exist in a determined way in a determined place, angels, because they have no dimensions, can exist only in a determined place in an undetermined way.

The image Lang uses, citing Scotus,

This radical rethinking of Aristotelian physics, catalyzed by medieval debates in angelology, allowed a new understanding of the relationship between bodies, place and motion that helped reformulate our understanding of the very fabric of the cosmos.

For Aristotle, motion was just inherent to bodies because bodies had natures that made them seek their natural place.

To posit angels as immaterial external forces was indeed oddly closer to a classical physics that sees an invisible force like gravity working on bodies externally.

In fact, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz accused

Newton of having introduced occult forces with his theory of

gravity, because gravity seemed to be a supernatural force acting on

bodies at a distance.

(Theologically, there is very little difference

between demons and angels in terms of their metaphysical make-up.

Demons are a subset of angels; they are

fallen angels.)

This being, in addition, has infinite computational power, which it can apply to calculate the trajectory of each atom.

Laplace believed this would yield infinite

predictive power, and this super-intelligence could therefore know

the entire history of the world and the ultimate future of the

Universe. Such determinism would later be called into question by

quantum mechanics.

His contemporary William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin) would label it a demon, and the name stuck.

'Maxwell's demon', still called so today,

revealed deep connections between information and entropy, evolving

our empirical understanding of the world.

It could travel at impossible speeds, teleport, and act at a distance.

to understand the physical

world and the cosmos...

Einstein, for example, will have read Pearson, and his antipathy towards using,

But could Einstein have achieved what he did without the precursory belief in angels?

Theology certainly motivated a search for alternative accounts relating place, movement and bodies. But although the nature of angels as a topic of focus was the catalyst for discussions about the physics of place, enquiring individuals also thought through angels to understand the nature of the physical world and its relationship to the broader cosmos.

And this yielded more complex notions of space, location and dimension, giving them new meaning. The role angels played in such thought experiments was unique:

In fact, this mediatory role was part of the logic of positing angels in the first place.

Angels do feature in the Bible, but Aquinas believed that a priori arguments could be made for angels precisely because the great chain of being couldn't miss any links.

Any gaps mean that human beings could not possibly make the jump to understanding God.

We need some intermediary knowledge that would bridge knowledge of God and knowledge of the world. This is why angels, as early as Pseudo-Dionysius in the 5-6th century CE, were equated with language.

Speech also mediates between the realm of ideas and the physical world.

Otherwise, all the work of angels could simply be

explained by God. However, angels, precisely because of their

intermediary status, allowed human beings to think about dimensions

of created reality that yet transcended our direct human

perceptions.

Studies in embodied cognition are showing that our knowledge is built upon our experience of the world.

George Lakoff and Mark Johnson's Metaphors We Live By (1980) shows how our bodily experiences come together to create complex metaphors, grounding abstract concepts.

Although occult forces such as angels and demons may be ridiculed in modern culture as 'hand-wavey' explanations of quite logical, down-to-earth scientific phenomena, I would suggest the inverse.

That what is most down-to-earth might in fact be to think about the invisible forces of nature as angels, agents, immaterial intelligences with certain properties familiar to us, but amplified.

Properties like agency and intention.

It is only in thinking through, and with, these more familiar concepts that we can then discover a less intuitive set of concepts, like spacetime, which require grounding in concepts like dimension, body, place and movement.

These necessary grounding concepts were

sharpened, historically, by thinking through the relationship

between the material and immaterial world, and angelology played a

significant role in their honing.

It seems that this imaginative framework resounds in the actual structure of how our thought operates. By virtue of this, angelology lay the groundwork for thinking through the nature of place, time and motion in quite complex ways.

Did angels and demons carve a conceptual space for the invisible forces that physics would later come to discover?

Though it may seem that the scientific and the

demonic are at polar ends of the spectrum when it comes to

explaining the natural world, angels and demons have actually shaped

modern scientific explanation as we know it today.

|