|

by Andrea Mustain

Staff Writer

06 April 2012

from

LiveScience Website

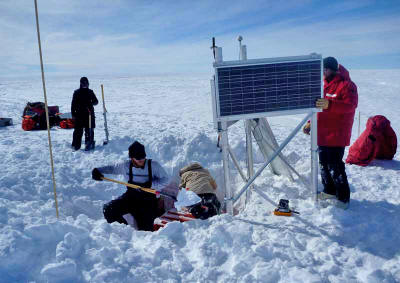

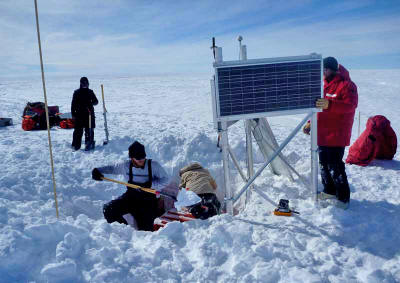

Researchers

hard at work around a seismograph,

an instrument in the

orange box buried in a hole in the snow.

Solar power runs the

seismic station during the summer,

and batteries keep it

going during the long, dark winter months.

CREDIT: Doug Wiens.

Thanks to a technological explosion in

the century since humans first set foot at the South Pole, Antarctic

research is thriving.

Yet despite the incredible scientific advances, there are still

gaping holes in some very basic knowledge about the frozen

continent. Namely, what, exactly, is under all that ice.

It's not simply a question for idle speculation. Figuring out what's

going on underneath the colossal Antarctic ice sheets is one

important puzzle piece in better forecasting what is happening to

the ice itself in a changing climate, some glaciologists say.

Scientists have used radar and other imaging technology to uncover

some astounding finds under the East Antarctic Ice Sheet:

A

vast

mountain range that rivals the Alps, and

Lake Vostok, one of Earth's

largest lakes.

But many scientists are trying to peer deeper still. They want to

map the rock that lies many miles beneath the bottom of the ice

sheet - in particular, the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

Sensors used to detect earthquakes are

helping in that goal.

The installation of

the seismograph network is part of a project called Polenet.

Here, traveling

researchers have set up camp for the night.

The camp faces north

toward Mount Waesche, left, and Mount Sidley, in the middle.

CREDIT: Mike Roberts.

Westside is

the quest side

Researchers have wanted to essentially perform a CAT scan of West

Antarctica's geological underpinnings to a depth of about 60 miles

(100 kilometers), said seismologist Doug Wiens, a professor

of Earth and planetary science at Washington University in St.

Louis.

"There are certain qualities about

Antarctica that make it particularly interesting," Wiens told

OurAmazingPlanet.

By installing a network of seismographs

- instruments that record the energy waves from faraway earthquakes

- to map out the qualities of the rock deep below the surface, Wiens

and a team of researchers hope to figure out "what effect the Earth

has on the ice sheet." The project is called Polenet. [See images of

the scientists at work in Antarctica.]

Seismograph data can help reveal how mushy the rocks are, and how

heat is distributed throughout them - a big deal for understanding

the network of mechanisms that govern changes in the ice sheet.

Because Antarctica has been covered with thick ice for many

thousands of years,

"the whole continent is pushed

down," Wiens said. "If you melted all the ice off, it would move

back up."

Charting how viscous the underlying

mantle - the colossal rocky layer directly below the Earth's crust

that, though rigid as steel, still "flows" - will help researchers

figure out how fast different parts of the continent would rebound,

he said.

"We think hot areas of the mantle

will flow easier, so they'll pop up faster," Wiens explained.

Cold areas, on the other hand, wouldn't

flow so easily.

"Sort of like molasses you've put in

the freezer," he said. "It doesn't flow, so it won't pop up very

fast."

The question of heat distribution and

flow from the mantle to the crust is also an important one, he said.

There is compelling evidence that watery-bottomed glaciers flow

faster - and scientists have observed a marked speed-up in many

Antarctic glaciers in recent years. However, it's not clear what's

driving the acceleration. Warming oceans are likely playing a big

role.

Geology might also be a factor.

"It might have a big effect on the

ice sheet and might explain some observations," Wiens said. "If

you have a large heat flow from the mantle in a given area, it

may form water at the bottom of the ice sheet."

Finally, seismographs can reveal hidden

sources of seismic activity - little earthquakes that could be the

signatures of active volcanoes hidden under the ice. [Antarctica:

Solving Geologic Mysteries]

Mount Sidley, the

highest volcano in Antarctica,

may have a lot of

company lurking out of sight.

Scientists are using

seismographs

to hunt for hidden

volcanoes in Antarctica.

CREDIT: Doug Wiens.

Success, at

last

This year, for the first time ever, Wiens and his colleagues have

the data in hand to actually fulfill this geological vision. Until

recently, Antarctica's brutal conditions destroyed instruments after

only a few months.

But improvements in batteries and data storage have allowed

researchers to run a network of about 35 seismographs since 2007,

enough time to get a decent picture of what is happening under the

West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

This last field season, in late 2011, a team trekked across West

Antarctica to retrieve seismographs that have been busily recording

years' worth of data. Researchers are now poised to begin the long

work of figuring out what it all means.

In the end, the work will reveal

long-held Antarctic secrets.

"It's really the first time we're

able to look at the interior structure of the mantle," said

Andrew Lloyd, a WSLU Ph.D. student who traveled hundreds of

miles by snowmobile to help retrieve some of the seismographs -

and the reams of data they recorded.

"It will enable us to say something really definitive about the

tectonics and geology of the region, which is something nobody

has been able to do before," Lloyd said.

Wiens said that the data are already

revealing a tantalizing picture of what is going on beneath West

Antarctica, a place that is, in the words of one scientist,

"hemorrhaging ice."

"We do see these big variations in

the temperature in the mantle across parts of Antarctica that

will have a big effect on the ice sheet," Wiens said.

However, he added, many months of work

lie ahead, and it will be some time before scientists are ready to

announce to the world what lies beneath the ice.

|