The USS PINE ISLAND (Navy Seaplane Tender) had pushed as far south as she dared in establishing an advance base from which to operate her seaplanes. There was still a couple of hundred miles of nearly solid ocean ice crust between her and that portion of Antarctica which we were to explore and photograph from the air. The skipper of the USS PINE ISLAND, Captain H.H. Caldwell, USN determined the leeward side of a huge iceberg, already located in the area, would provide the best protection for seaplane tending operations. We were Crew #3. Our plane, minus it's wings (which were stored overhead in the ship's hangar), was secured to the ship's afterdeck (fantail) by tie-down cables; the tail section was protruding far past the stern over the ocean. This was our duty station where we spent the major portion of each working day performing preventative maintenance, practicing emergency drills and speculating about our first flight into the unknown. The pilot was windmilling the plane around on the water a few hundred yards from the ship waiting for us to come out in the rearming boat and relieve him and his crew for the next flight. The surface conditions had worsened by now and the swells were enormous and rough.Relieving the crew on GEORGE 1 from the first flight was one of the wildest experiences I had ever encountered.

Even boarding the rearming boat from the lee side (sheltered from the wind-chopped sea) of that huge tender, which was hove to in the lee of "Old Bessie" (my nickname for the tremendous iceberg the ship used for protection), was extremely rough. With our flight rations and water breakers (drinking and cooking water containers) aboard, we headed for the plane. Once clear of the protection of "Old Bessie" and the USS PINE ISLAND, we were in some very wild water. The Boat Coxswain had to make three passes (approaches to the plane's starboard waist hatch) before we could secure the boat to the starboard side of the plane. To further indicate the sea conditions, transferring crews and flight supplies was an exceedingly hazardous experience in itself. The after hatch, fully open with hatch doors tightly secured in this position, measures approximately 5 feet square. We had to time the transfer of each piece of equipment and each person so that the pass through the hatch opening was made when it was clear of the boat gunnel. Visualize the hatch opening and closing constantly over the padded gunnel of the rearming boat. Of course, if the timing was not just right when you went through, you could have been crushed between the bottom of the top of the hatch as it came down, and the boat gunnel as it went up. Finally, the transfer was completed with no casualties. The rearming boat was headed for the tender with the relieved crew safely on board. Now commences another difficult task, the refueling operation. First, we taxied as close as we dared to the lee side of the tender. Then two rearming boats secured themselves to us, one to our starboard and one to our port side. Engines cut the boats took over, edging us up to within securing line and fuel hose range of the ship. Even though the USS PINE ISLAND was on the lee side of "Old Bessie", and we were on the lee side of her, it was still so rough that the rearming boats had to keep the engines running in order to maintain the proper relationship for fueling between GEORGE 1 and the ship. I was the only crew member in the after-station. Thank God the skipper of the USS PINE ISLAND, Captain Caldwell, had come along as an observer and was back in the after-station with me. Frenchie called back on the intercom and told me to load the JATO bottles while we were in this "relatively" calm status. He asked if I had anybody to help me, since these JATO bottles weigh between 80 and 100 pounds each. Ordinarily, this task is the Ordnanceman's responsibility (and always a two-man job) but someone, for some strange reason, decided an Ordnanceman would not be required for this Expedition. Fortunately, I had assisted in loading JATO bottles many times before. I asked the Captain if he would give me a hand and he stated "just tell me what to do." What a guy! So I reported to Frenchie that the Captain was here and would be glad to help. Imagine me, Aviation Radioman Second Class, having the Ship's Captain for an assistant! It was a good thing Captain Caldwell was a giant of a man! He was able (even though it was extremely rough, and nearly impossible to stand) to hold each bottle high enough and steady enough for me to align them properly and lock them in the mounting shackles on the waist hatch (the after-station hatch doors). The ignition wires were not yet connected, as a static buildup of electricity could set them off. Can you imagine the havoc this would cause?!! I reported to Frenchie the JATO bottles were loaded and he acknowledged telling me not to connect the ignition wires yet. We were still refueling and I noticed the lines securing the rearming boats through the waist hatches were tearing the aluminum skin of our plane from the lip of each hatch, port and starboard, all the way to the main structure supports, approximately 6 inches. I reported this to Frenchie and he advised waiting to see how bad it was after we were free of the boats, with both hatches properly secured in the ready for takeoff state. Upon completion of refueling, the steady lines were released from the plane and hauled back aboard the tender, along with the fueling hose. The rearming boats (still tearing violently at the securing lines to the plane) pulled us free and clear of the ship With engines running, we signaled the boats to cast off. Once clear we (Captain Caldwell and myself) immediately secured all after-station hatches for takeoff. After pounding and bending the torn hatch lip back as close to its original condition as possible, I discovered the hatches would close and lock OK. The hatch doors are designed to lock closed one half at a time. This permits the forward half (which the JATO bottles are mounted on) to be locked closed, with access through the after half to hook up the bottles, prior to commencing the takeoff run. Fortunately, everyone proved to be good sailors, otherwise, we'd all have been deathly seasick by now! I reported to Frenchie, "after station secured and standing by to connect the JATO bottles." Frenchie had radioed the ship to lay a big slick (a smooth area created on the water by a ship moving rapidly) for us as the water was too rough to attempt a takeoff without one. If the ship moves in an arc, it creates an area large enough to assist greatly in the start of the takeoff run. In extremely rough water this is necessary, otherwise, the plane would tend to porpoise badly and probably swamp out the engines. Frenchie told me to connect the JATO bottles but to be certain there was no static electricity on the plane's connectors by discharging them with a screwdriver before connecting the wires. I did so and secured the waist hatches reporting, "JATO bottles connected and after-station secured for takeoff, Sir." As power was applied and we picked up speed, I noticed water was shooting in from the tears in the hatch seams on both sides as if a fire hose had been applied under full pressure. I immediately reported this to Frenchie. He told me to keep an eye on it and as long as the water did not rise above the decking, we should be OK. At this reply I thought, "this guy really knows the limits of a PBM!" I later discovered how Frenchie managed to make that takeoff under the absolute worst conditions I had ever heard of. The slick did provide considerable assistance in getting started. The plane was extremely heavy, with a full load of fuel and plenty of ocean! Frenchie knew it would take a very long run to get the plane on the step before firing all four JATO bottles to accomplish the final lift off. The step is that part of the hull shown below:

I could not understand how he kept us from porpoising severely while hitting those gigantic waves as we gained speed. I did notice we were going right through the top of them and not dropping into the troughs. This, of course, allowed us to pick up the necessary speed. Frenchie later told me that he had Lt. (j.g.) Kearns (co-pilot) help him muscle her through. They both pulled the yoke (double yoke in PBM's - one for pilot and one for co-pilot) back as hard as they could when coming out of each swell (this kept her from dropping into the troughs) and pushed the yoke as hard as possible when going into each swell. This continuous muscle action lessened the tendency of the ship to porpoise until (finally!) enough speed was attained wherein we were just hitting the tops of each wave. At this point, Frenchie fired all four JATO bottles which gave us the added lift we needed. At long last, we were airborne. That was, by far, the longest takeoff run I have ever been in, or heard of. It was at least two miles! Fortunately, the ocean water never did rise above the decking, but we were still carrying a tremendous amount of it. Once well clear of the water, I hung my headphones up and reported to my "in flight" station on the flight deck. The Captain went forward to the observer's seat in the bow. The bow gun turret had been removed specifically for this expedition, and a comfortable seat in a clear Plexiglas dome had been installed in its place for viewing purposes. The view would have been fantastic from this position had the weather been nice. At this point, I would like to comment that in my mind I feel confident that no other "P-Boat" Commander in the Navy, before or since, could have negotiated that takeoff. If I have succeeded in describing all the conditions clearly, the reasons are obvious. In my opinion, Frenchie (now Lt. Cdr. Ralph P. LeBlanc, USN, Ret.) will always be the greatest PBM pilot the Navy has ever known! It took us quite a while to obtain an altitude of a mere 800 feet. We were flying in a snowstorm now and the visibility was ZERO - ZERO. Believing the weather conditions as previously reported were CAVU (ceiling and visibility unlimited) over the coast, and knowing my radar was working fine, I was not worried. Frenchie had been on the pre-established course for the coast since lift off. Double checking my radar scope, I observed what appeared to be icebergs all around, which provided good returns due to their size and solid surfaces. The coast was not yet visible on the radar scope since we were quite low and still 200 miles out. Flying at this low altitude provided us some hazy visibility as we emerged periodically from snowstorms. I knew icebergs by their appearance on the radar scope because just previous to this operation, I had flown radar on OPERATION NANOOK and my familiarity with these weather conditions, icebergs, etc. was well established. In fact, I had received a commendation for my performance on the radar during one flight in that operation. We had just flown over the North Pole and started to return when the weather socked us in tight. There was no way we could climb over the weather as it extended to 40,000 feet and a PBM's capability is only up to approximately 20,000 feet. So we stayed low and I read the radar to the pilot all the way back (for some 9 solid hours.) Oh well, that was another day! As we approached the coast, I kept a constant vigil on the radar scope, informing the pilot of any significant changes. The last reading was "mountain range twenty miles ahead and scattered icebergs." This was in total agreement with our charts. I continuously verified my radar indications with the Navigator's chart. Frenchie was preparing to do a "180" and return to Base as the weather was not clearing at all; in fact, it seemed to be getting worse... Then, all of a sudden, it felt as if we had hit a slight bump. Frenchie immediately poured on full power, starting to pull up and turn - and all I remember was the sensation of floating! The next thing I knew, someone was shaking my shoulder. I looked up, from an apparent crouched position in the snow, and saw our little flight engineer, Warr, looking down at me with tears in his eyes. My first comment was,

His immediate reply,

I had apparently been knocked out and, as things started to get a little clearer to me, I looked around and it became obvious that Warr's comment was undoubtedly the understatement of the year! At this point I would like to relate exactly why we exploded. When we felt that bump, we had torn a hole in the hull and the hull tank began leaking profusely. The 145-octane fuel was ignited by the engine exhaust flames. BOOM! -- 1,345 gallons most likely created the largest aircraft explosion ever, and how! As a radar operator with vast polar experience, I couldn't believe this had happened. It has now been determined that this "no returns" phenomenon was the first-ever "stealth radar" happening. The uncharted area from the coast to 800 feet in altitude where we hit was such a gradual incline that there was nothing for the radar to see.

Warr stated that he thought he was the only one left alive. He was blown down hill, in the opposite direction from the rest of us, and being very light in weight had landed quite a distance from us. He never lost consciousness and described turning over and over in the snow flurries and finally coming down, rolling over and over in the soft snow, far below the crash site. He immediately began walking back up hill into the smoke, the only indication of which direction to go, looking for the rest of us. Imagine how he must have felt after trudging up hill, in the blowing snow and smoke, for a couple of minutes with no sign of life anywhere. No wonder there were tears in his eyes when I first saw him!

The

Flight Deck was on its side with the flames roaring across it.

And poor Frenchie, he must have been the only man in the plane who had his safety belt fastened (as everyone is supposed to), and there he was, hanging by it in those roaring flames. Needless to say, he was terribly burned. It was a good thing Bill Kearns knew exactly where Frenchie was or he would have been burned even more severely. Warr and I, in that split second of time, were still trying to locate exactly where his cry for help was coming from. We knew we had to find shelter for Frenchie, out of this snow storm, immediately! The tunnel section of the plane was the only part left intact which could be utilized for shelter. We carried Frenchie into the large end of it, where it had been ripped from the main hull by the explosion. We were able to locate one sleeping bag in which to put Frenchie, and carefully set him down on a smooth section of the skin between two of the structure braces. We spread a parachute over the jagged, busted, open end to keep the wind and snow out. Bill Kearns stayed at Frenchie's side and applied sulfur powder to the exposed burned areas.

We found

Captain Caldwell standing a short distance from Williams, near the edge

of the flames. He must have been blown right out the bow. His physical

condition appeared good, although a little dazed.

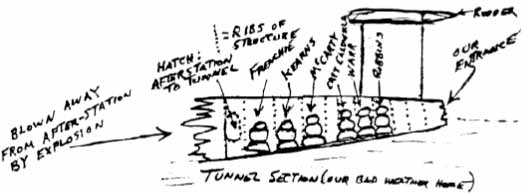

I cannot recall exactly where we came across McCarty (the Chief Photographer's Mate from the ship). I believe he had stationed himself in the tunnel section prior to the crash. His electric flight suit and earphones had been plugged into the control box at the tunnel hatch station from where he would be shooting pictures later on. McCarty had crawled out of the tunnel section holding his head in pain. He had evidently been slapped around, inside the tunnel section, quite severely. There was a huge gash in the top of his head, however, the cold had already begun coagulating the blood. McCarty might have bled to death had it not been for the extremely cold temperature. There were three sleeping bags available at this time. Frenchie and Bill Kearns each had one and were already located inside the tunnel section up next to the hatch (leading from what originally was the after-station). We gave McCarty the other one and located him next to Bill and Frenchie. There was one blanket between Captain Caldwell, Warr, and myself. We decided to bed down in the tunnel and wait for the storm to subside. Accurately describing our temporary quarters would be quite difficult, if not impossible, so here, to the best of my recollection, is a drawing of the situation:

Our entrance was established by the fact that the Plexiglas in the end of the tunnel section was gone. The other end had a hatch which was functioning properly so we had a good ready access to Frenchie and Bill. Incidentally, I failed to mention earlier that Bill had been blown through the windshield and was keeping his right arm in a sling he had made from his flight scarf. We later discovered his shoulder was dislocated and the upper arm was shattered. No compound fractures, Thank God! It is a good thing our wristwatches kept functioning, otherwise, we would never have known what part of the day it was (it was daylight around the clock). The three of us (Captain Caldwell, Warr, and myself) bedded down in the tunnel under that single blanket. We would rotate the center position from time to time to share its warmth. Williams was able to call my name and each time he did I would go out and offer words of encouragement, making certain he was as comfortable as possible and shielded from the snow. I must have been the only one he knew by name. I know we were all quietly praying, especially for Williams and Frenchie. When the weather subsided a little (I do not recall exactly how much time had elapsed), the Captain, Warr, and I went outside to survey the situation. Williams had not called my name in a while. We went straight to him; he was gone. I do not believe he suffered at all; we certainly hoped and prayed not. From time to time, even to this day, I often hear Williams calling my name (in my sleep, of course). We buried our dead and the Captain held services for all of them - Lopez, Hendersin, and Williams. At this point, you can well imagine how much the rest of us wondered what our fate would be. The first three days, the weather was exceptionally bad. Lots of snow and very dark overcast. As the weather permitted, we searched the debris for anything that might be of use to us. Near the area that use to be the after-station close to the tunnel, we located three large boxes of Pemmican. Each box contained about 100 eight ounce paper cups of this stuff. Pemmican is an especially prepared ration containing all the nutrients necessary for a healthy existence. It tastes terrible! I must add at this point that the pemmican of 50 years ago did in fact taste terrible. I hear it tastes good now. In those days flavor was not important for emergency rations. However, we knew we could get use to it if we had to. Presently, we were using the flight rations we located earlier. They consisted of steaks, potatoes, canned vegetables, butter, bread, salt, pepper, sugar, canned milk, and a few cookies. We even located two one gallon cans of good old Navy peanut butter! We had plenty of food for quite a while and I felt the Pemmican would get us through the Dark Season if need be. All of the fresh food was located in or near the area that would have been the galley (right beneath the flight deck). We had to dig it out of the snow. I acquired most of the sugar by separating it from the snow by taste. We had located a small two burner gas pressure stove in the emergency supplies - but no fuel. We had a couple of bombay tanks full of 145 octane still intact, so I tapped one of the fuel lines (by removing two hose clamps and a short piece of rubber hose) and plugged it up with a rag. We now had enough fuel to last us all year. We had also located our two pressure cookers, so we could cook quite well. I had done a lot of in-flight cooking in PBM's before, so I acquired the job of being the "Duty Cook". Oftentimes, when anyone wanted something to eat, they would call "Hey Cook" - so, another nickname. My main menu was "Pemmican Stew" - consisting of chopped up steak and Pemmican, salt, pepper, and water. Very little Pemmican at first - we knew we had to start getting use to its terrible taste. It camouflaged pretty well though. We were also having a hot vegetable. The real grand finale was my dessert - "peanut butter and snow sundae", consisting of a "glob" of clean snow (always careful to stay away from the yellow snow, of course!), canned milk, sugar, and topped with a mouth-savoring, delicious "blob" of peanut butter! Everyone thought it was great! Except poor Frenchie. His face had been burned severely. His mouth was burned to the point that he had to break his lips open with the fingers of his one good hand. He could not move his mouth much or it would break open at the corners and bleed. I kept Frenchie on a special buttermilk diet, prepared by heating canned milk and adding a small amount of butter and sugar. Sometimes, I would add slight variations as long as everything could be completely liquid. Bill Kearns would feed him. Frenchie never complained. It was even difficult for him to talk. He learned to manage quite well without moving his mouth at all. Bill patched him up as best he could with sulfur powder and added more whenever he felt it was needed. Bill discovered areas of his back and side were severely burned, and even part of one eyelid was burned away. We did not believe he had a chance of surviving unless, by some miracle, we could be rescued right away. I kept the burners going constantly for melting snow, trying to fill the two or three water breakers (cylinder shaped water holders that held about 4 or 5 gallons each) which were available. Seems as if it took 15 or 20 pots of snow to make just one cup of water! I'll never forget melting the first pot of snow and wondering where the water had gone!! As the weather permitted, the Captain and I would crank the handle of the Gibson Girl (emergency transmitter). Sometimes I would send CW messages with the manual key button while the Captain or Warr cranked, but most of [the] time we just left it in automatic and it would transmit a pre-programmed emergency message. Sometimes we were able to get the kite antenna up in the hope that we would get better range. Warr and I later built a fixed antenna (from the remains of the plane's original antennas), about 50 feet long, and secured it to the highest points of the wreckage. This allowed us to sit inside the tunnel in inclement weather and transmit constantly. It was encouraging for all of us just to see the light glowing on the Gibson Girl, telling us she was loading the antenna OK and should be radiating (transmitting). The weather didn't really break clear until the third day. By this time, we were fairly well set up. We were still very anxious to survey the area in good weather so we could really get the BIG PICTURE. We scrambled outside into the clear, bright sunshine, at first just drinking in the beauty of it all! Then, suddenly, the bright glare became too much. Some of us got headaches; we knew we had to get our snow goggles on immediately. That was a good lesson; I do not think any of us ever forgot to wear them again. The Captain's ankle was bothering him (we later learned it was broken), so Warr and I did most of the hiking around. We spotted a few dark objects way down the hill, so down we went to retrieve them. Three perfectly good sleeping bags still rolled up tight! This made us very happy, for now we all had our own sleeping bags. We were able to locate the rest of our emergency supplies - sled, first aid equipment, signaling equipment, more emergency rations, etc. I even found a Brownie Box Camera with film in it (I believe it had originally belonged to Mr. Lopez). I set it in the sun to dry out. It seemed to be OK but I wanted to give the film inside a better chance. At the captain's suggestion, Warr and I took one of the nine-man life rafts and spread it out about 40 feet down wind and down hill from our site. We then proceeded to locate everything we could find that was highly inflammable and piled it all in the raft. Powder from Varies pistol shells (after we discovered our Varies pistol would not work), powder from drop flares, solid fuel (was part of the emergency kit, but they had neglected to pack the stove with it), and anything else that would burn well. Nothing, of course, which we might be able to use later. I rigged a long-handled torch by joining (they snap together) three oar handles and wrapping a rag around the paddle end. Our signal fire was now ready to be doused with gasoline and ignited at a moment's notice. Fortunately, we had plenty of dry matches in our emergency kit and, I believe, everyone had his own lighter. During Survival Training, prior to deployment on this expedition, we were notified that cigarettes would be the least of our worries as we would lose all the desire to smoke. Most of us were heavy smokers and an ample supply of cigarettes were aboard the plane. During our thirteen days on the ice we never lost the desire to smoke and enjoyed our cigarettes very much! One nice day we were in the tunnel cranking on the Gibson Girl, and swapping sea stories when we noticed McCarty was not with us. Then we heard him rummaging around outside. Shortly thereafter, he crawled in with a very pleased expression on his face and told us he had pitched himself a tent (there were three pup tents in the emergency supplies) and looked over at the Captain and asked him if he would like to share it with him. Needless to say, the Captain accepted and thanked him. Sleeping between the ribs of this tunnel section really was not all that comfortable, especially for the Captain, for he was a very big man. Warr and I had previously set up a tent as a supply container only. This is where we stored all the food and goodies we might be able to use later. However, at that time we preferred the protection of the tunnel to sleep in. Now the weather was much better; in fact, it was beautiful! Not a cloud in the sky. Warr and I decided to set up our own tent. It was quite cozy and comfortable inside and the sleeping bags made it very nice. We had not been asleep more than two hours and I awakened to discover that I was having difficulty turning over. Suddenly, I realized my body heat had caused the snow to melt under me and there I was wedged in my own mold! Warr had the same trouble so we scouted around for a couple of pieces of decking. We found two pieces that were just the right size and slipped them under the canvas flooring of the pup tent. Our problem was solved. McCarty and the Captain did the same thing. The first clear day, after our housekeeping was well established and all the provisions we could locate were safely stowed in our supply tent - plus completing the fixed antenna for the emergency transmitter, I began to check out the aircraft RAX receiver. It appeared to be in good shape. This was the receiver we were using for communications with the Ship at the time of the crash. Nothing broken or burned. It looked as if it would work providing I could get the dynamotor (Receiver's power) running. My first thought for a good source of auxiliary power was the aircraft's Lawrence APU (Auxiliary Power Unit). It was a hand start (pull rope) type and we had plenty of aircraft fuel to operate it. It was on it's side and a good distance from our portion of the crash site. Our first disappointment was easily amplified by the fact that the pull rope start shaft was severely bent and jammed against the engine. No way could we ever use it. I discovered one of the aircraft's batteries had not been completely destroyed. The end cell was gone (busted off) but the other three looked good. I tore some wiring from the aircraft's harness and commenced making the electrical hookups necessary to give the receiver's dynamotor some input power. The instant I touched the return lead to the battery's negative terminal, the dynamotor jumped into action and produced one of the most beautiful sounds we had heard since our disastrous arrival. Everyone let go a loud cheer of approval! I plugged in the head phones, turned up the volume and alas! - no receiver background noise at all. The unit was still dead. Possibly the three cells of my crippled battery were not driving the dynamotor fast enough. I removed the voltmeter from the Flight Engineer's panel and discovered the battery was only producing about 16 volts. Apparently this was not adequate since, normally, 24 volts are used. It sure sounded good at first though! Later that night (or what should have been night) while lying in my sleeping bag and contemplating this problem, it occurred to me that I had seen a case of flashlight batteries somewhere in the debris. I was finally able to get to sleep with the exciting idea in mind of taping a string of them together and tying them in series with the remaining cells of my aircraft battery. I would now have the voltage necessary and we might be able to monitor the circuit from the good ole Pine Island again. I was never able to test my theory as we were awakened by Frenchie yelling (as best he could) "Plane - Plane!" I have had many dreams about correcting this receiver problem and actually being able to receive messages from the Ship. We were later informed the ship transmitted messages of encouragement every hour on the hour for the entire period we were gone. Our first contact with the rescue plane will be discussed after all the experiences that occurred during our 12-day ordeal on the icecap have been detailed. We had beautiful weather after the first three days and, after four continuous days of the same, we began to wonder why no rescue plane. We could only assume the weather conditions at the ship, 200 miles from us, must still be severe and we knew that no flights would be directed to take off in inclement weather. We managed to keep ourselves busy (those of us who could) and often occupied our minds by playing Salvo after we were bedded down. Salvo is an old Navy game and can be played by only two people. Each draws 100 squares on a piece of paper (or whatever), letters each row across the top, numbers each row down the side, and then places his ships (Battleship, Cruiser, Destroyer, Destroyer Escort, etc.) by abbreviations in whatever squares he desires. Then each takes a shot at the other's fleet by calling out a square by it's letter-number designation (A1, B5, etc.). Each hit is indicated by the opponent until one's Fleet has been completely sunk. The first to sink the other's entire fleet naturally wins the battle. We had a lot of fun with this game. We only ate one meal a day and drank a lot of coffee. Boiled coffee is good stuff. After being out there some 10 days we began to think in terms of having to make it through the entire dark season until the following summer when somebody might try to get in to us again. You see, we thought they had been receiving our Gibson Girl transmissions all along. Had we known they had not heard anything at all since the day we left, one can well imagine how we would have felt. So, once again, what you don't know won't hurt you! On one of the particularly beautiful sunny, clear days, we (the Captain, McCarty, Warr and I) were enjoying the sun. In fact, we were actually sunbathing. There was no wind at all, and the warm sun felt very good. Bill remained in the tunnel with Frenchie, always by his side. We were forever and always grateful to Bill for the good care and close watch he kept over our badly burned and very courageous Plane Commander! Still sitting on the wing enjoying the sun, I looked at the other guys and commented, "You guys sure look like a bunch of grubs!" I cannot remember who made this reply, but one of them said, "You don't look so hot yourself, Robbie; your left eye has been completely closed ever since we arrived!" I could not believe this - I immediately reached for my left eye and sure enough, my eye was tightly closed and felt very puffy. I had to see this! I scrounged up a signal mirror from one of the life raft emergency kits and WOW! - I couldn't believe my good eye. The whole left side of my head was swollen way out, black and blue. I was not sure, in that puffy looking area, where my left eye was located. My mind was immediately relieved when I forced the eyelids open and discovered my vision was not impaired. I find it difficult to believe I accomplished so much the first three or four days without realizing my left eye was completely closed. Since the weather was so nice, the little Brownie Box Camera (I had drying out in our tent) came to mind. We all agreed it should be OK to use by now. I believe Mr. Lopez had just loaded it with film before we left. Anyhow, I managed to get good close-up snaps of the others (except Bill and Frenchie as it was too dark inside the tunnel), using different angles of the wreckage as back drops. Using the film sparingly, I also snapped shots of the flight deck, Flight Engineer's panel, the wing , and engines. I combined as much as possible into each snapshot. We knew if people could see the total devastation of this plane they would never understand how anyone got out alive. When the film was used up, I carefully removed it from the camera, wrapped it in a piece of cloth and dropped it in my flight suit leg pocket and zipped it up. Someone said to put it back in the tent in case it needed further drying. I did not want to do this as I was afraid it would be forgotten. After thinking about it and being assured they would not let me forget, I placed it back in the tent for what we all thought was the best thing to do. Yep! You guessed it - that roll of exposed film is still right where I left it. Boy! Could we use it now! I know I would give my eye teeth to see those snaps, and I believe a lot of other people would too. Warr and I had previously found a 12-gauge shotgun with the stock blown off (never did locate the stock) and two shells. We had placed the shells along side the box camera to dry out. I left the gun in there also (along side my sleeping bag). There were some huge Arctic gulls that kept hanging around - and I don't mean just flying around - I mean right on the snow only 25 or 30 feet from us. This was beginning to get on our nerves, especially feeling they were just waiting for us! They were probably some kind of albatross, resembling an oversized seagull both in color and shape. However, their bodies were evidently loaded with some type of heavy yellow oil or grease, as was apparent by large blotches over what would have been the white plumage of their bodies. We were later to learn they were Skuas (the vultures of the Antarctic). With the weather so beautiful, and the hungry looking gulls standing out there waiting, it came to my mind that this might be a good time to try for "Arctic Gull Stew". We knew it would be much better to have them on our menu than vice versa. Besides, we needed a little action! I crawled into our tent and returned with our only shotgun and the only shells (2). I popped the breach a couple of times, worked the trigger mechanism and everything seemed to be in good working order. Someone said, "You better not try to fire that damn thing, it might blow up in your face!" This kind of encouragement I did not need. I was having a tough enough time trying to figure out how to hold it. The no stock bit made it sort of scary. Finally, I mustered up enough nerve (or whatever) to get the show on the road. These birds had evidently never seen humans before, consequently, they showed almost no fear of us at all. I dropped a shell in the chamber and started walking slowly toward three of them. When they were only about 25 feet away, I stopped as they appeared to be getting a little nervous. (I was very nervous!) I held the gun as far out in front of me as possible, aiming point blank at one of them. As I was squeezing the trigger, I remembered the warning about the gun blowing up and turned my head in the opposite direction . . B-O-O-O-O-M-M-M!!! I looked back and the three gulls were just standing there, looking quite placid, as if nothing had happened. I must have pulled the shot way off when I turned my head. I hadn't even ruffled his feathers! My audience got a big charge out of that and laughed uproariously! Now that my confidence was up and the gun seemed to fire quite well, I was going to make a definite score with the last remaining round. I chucked the last shell in the chamber (mind you, the damn birds were still ignoring me!), took careful aim and fired. My target flinched only ever so slightly, took a look at his buddies, glanced at me and decided to make a slow, nonchalant takeoff. My audience really roared! I said,

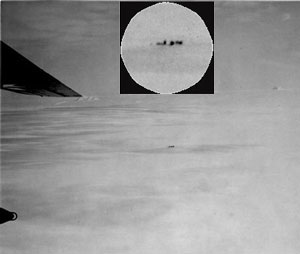

Besides, these shells were loaded with very small shot. But, to this day, I still cannot believe I didn't hurt that guy more then he indicated. At least one thing was accomplished - they all left the area (for a few days anyhow).We have been here twelve days now, the past nine of which the weather has been absolutely beautiful! We knew the weather had to be bad at the Ship or we would have seen one of our other planes long before now. Our little community was quite well established and our daily routine was well filled. I was the Chief Cook and Bottle Washer (with considerable help from Warr and the Captain). The Captain's ankle was apparently doing well (he never complained!) McCarty's deep gash in his head had healed over quite well (he did complain of headaches from time to time). Bill's arm appeared not to bother him as long as he kept it immobile, and he stayed constantly at Frenchie's side. It was difficult to tell how Frenchie was really doing. He seemed fairly cheerful at times, even wise-cracking occasionally - quite a guy! And, Warr and I were in the best of health. Early morning on the thirteenth day, someone yelled "PLANE", "PLANE"! and we all came scrambling out. The engine noise was fading away as we could barely see her in the distance about to go out of sight. I grabbed the canvas bucket, pulled the plug on the bombay tank and filled it with 145 octane gas, doused gas all over the life raft we had previously set up for this, then soaked the rag on my long handled torch. I could not get it to light and the plane was almost totally out of sight. I stepped up to the raft, with those gas fumes pouring off, and ignited another match. BOOOOOMMMM!! Everything seemed to explode in my face - no chance to turn away! Everyone cheered as a huge column of black smoke went pouring skyward. I blinked to insure my vision was still OK. Captain Caldwell had been watching me closely and asked if I was all right. I told him I thought so, but I wasn't too sure! As soon as it became obvious I was OK, he grinned broadly at me and stated that I was very lucky to get off with only my eyebrows and eyelashes singed off. We watched the speck in the sky that had been disappearing rapidly. Suddenly, it was apparent the speck had changed course and was fast becoming larger and larger. We cheered with wild abandon! Tears of joy and thankfulness were in evidence as we realized our prayers had finally been answered. Little did we realize the grueling ordeal ahead.

So,

Lt. Ball dropped us a weighted note which read,

The lake he was referring to was a huge area of ice-free expanse in the ocean crust just 10 miles from us large enough to land one of our PBM's in. The "know-it-alls" stated that a huge iceberg must have broken off and the current moved it creating this ocean lake. B.S. We had clear visibility, when we started from the crash site, all the way to the horizon from 800 feet up and there was no iceberg anywhere. To this day, I know the BIG GUY IN THE SKY had a lot to do with the creation of that lake; otherwise there would have been no way to get us out. If I ever had doubts before, this certainly erased them. Needless to say, I have been a firm Believer ever since! We had previously surmised a helicopter rescue might be possible. However, we later discovered they had been trying to get close enough to the coast to establish a good helicopter range for days, and no way!! The very heavy, thick and solid ocean ice crust stopped them cold. The Captain read the note aloud and asked us what we thought. It seemed like a darn good idea; besides, we all knew there was no other choice. We joined hands and formed a circle in reply. We commenced preparations to move out immediately. We assembled our sled (part of the emergency equipment). It was a leather thong tie-together kit and it worked amazingly well. Also, the main frame joints were inter-locking. We made a bed on the sled by placing three sleeping bags on it in such a manner that "Frenchie" said he was quite comfortable. Some guy!! He never complains! We all knew this would be a very painful ride for him. We packed all we thought we might need, including a water breaker, around Frenchie and tied it all on. I noticed from our present vantage point, 800 feet up, according to the barometric altimeter in the Flight Engineer's panel, we could readily see the lake. But it was quite obvious that once on our way down, we would lose sight of her for long periods of time. I removed a compass from the instrument panel (still intact, believe it or not) and set it on the back of the sled where the driver (Yours Truly!) could establish and maintain the correct course. We pushed off immediately, having no idea of how long it would take or what obstacle(s) yet lay in our path. The first part of the trip was quite enjoyable for me. It was all down hill. I was riding the runners and steering the sled by digging my heels into the snow, right heel for right turn and left, for left. Needless to say, the experience was totally new to me and quite exhilarating. I know it was rough on Frenchie, but he kept assuring me he was fine. We were quite some distance ahead of the rest of our crew when the sled came to a halt. We had bottomed out in a gully (smoothly, that is) and decided this was a good place to wait for the others. We could no longer see the lake at all, but I had the course marked on the compass, and was not worried. The rest of the group was glad we had stopped. I discovered they had been yelling at me to "wait for them" for some time.

While

resting at the spot where the sled had stopped, LT Ball dropped us a

note indicating he had to return to the Ship as his fuel was getting

low and for us not to worry; the other plane, with Lt. Cdr. John Howell

in the cockpit (he was the Senior Aviator in Charge), was on the way.

We pushed on, this time pulling the sled. The Captain's ankle was bothering him considerably - made obvious only by his limp. He also NEVER COMPLAINED. There were no pulling areas that were difficult, only very slight inclines or level terrain; the rest of it was all down hill, and "Yours Truly" was having a ball in his new field of endeavor, sled driver! The Captain, Bill, and McCarty all wanted to help with the sled, and did get a hand in from time to time. But, the going at this time (all of which was primarily down hill stuff until we reached the coast) was very easy and, for the most part, no more than riding and driving the sled. Maybe I was a little selfish with my sled driving, but I enjoyed being right there with "Frenchie" all the way. I know that long walk (even down hill) was tough on the others, but no one seemed to mind and there was certainly no room on the sled. We had been traveling quite a few hours now and making pretty good time. Once again, I was quite a distance ahead of the rest, and the slope was getting much steeper as we drew closer to the coastline. I guess I was feeling those belts of Old Crow more than I realized as I heard the Captain shout,

I dug my heels in hard and we stopped almost immediately. Sure enough, only 20 or 25 yards ahead was a sheer drop-off! We had reached the Coastline; now the most grueling part of the trip was to start. Meanwhile, Lt. Cdr. John Howell had relieved Lt. Ball in the air surveillance coverage of our trip. He came in at what appeared to be an altitude of about 3000 feet (maybe higher). I guess he was a little leery of the area as he maintained this altitude throughout his patrol. Shortly thereafter, he arrived on station (on station is an aviation term meaning the designated area of patrol) and notified us by drop-note that he was going to land on the lake and wait for us, as a fog bank was beginning to roll in. He knew he would have to save as much fuel as possible and landing in this totally strange area might prove to be a problem. We were able to watch him touch down; he negotiated the landing beautifully! Sure enough, shortly after, the fog bank moved in and obscured him from our vision. Believe me, it was a tremendous relief for us to know we now had somebody down there waiting for us. For my money, that landing was a very "gutsy" thing to do. We knew he had made many passes over the landing area, insuring himself it was clear of ice. Even so, 1345 gallons of 145 octane in your main hull tanks is enough to make anyone up tight knowing that area of the hull touches the water first at about 100 miles an hour. And, all of us had been briefed on how sometimes certain types of ice chunks, or small bergs, may not be seen above the water. This is where our 2nd hand from "the big guy in the sky" came in. How, in God's name, will we ever get down the face of this mini glacier to the smooth ocean crust! Presto! Just to our left is a trail large enough for the sled, all the way down with easy passage over a few crevasses at the bottom to the smooth ocean ice crust. Remember now -- this is exactly where we happened to arrive at the ocean. Now how, exactly, could all this wonderful good fortune happen to be right where we needed it? Now you know why we all became true believers! We were able to negotiate the narrow ledge quite well. The worst part was lifting the sled over a large crevice at the bottom. Everyone helped here. Once out on the smooth ocean crust, we knew we had it made. The sled glided right along with very little pulling involved. Walking became easier because there was not so much of the powdery stuff on top; except for poor McCarty. He kept falling through all the way up to his hips. None of the rest of us had this problem. Sometimes we would have to stop everything and pull him out., but most of the time (with a few words of encouragement from the Captain), he would fight his way back on top. Why only McCarty? I am not certain, but I believe his weight combined with his comparatively small feet must have created the problem. However, this only hampered him for about 35 yards - it must have seemed like an eternity to him!

From the time we started on the smooth ocean crust, we were in the fog bank discussed earlier. It was not a very dense fog and we knew our course. Besides, "Iron John" ( our nickname for Lt. Cdr. Howell) was windmilling (idling and blipping the engines) around in the lake, and the engine noise was excellent verification to us that we were on the right course. After traveling about half the distance from the coast to the lake, we were met by the Photographer's Mate, Dick Conger, from "Iron John's" crew. He and "Iron John" had come ashore (the ice shelf around the lake) in one of the plane's nine-man life rafts, and had pushed out to meet us and give us a hand. The fog came in very thick and heavy. Conger led the way to the rendezvous area where they had pulled the nine-man life raft up on the ice shelf. We decided to wait in hopes the fog would lift soon. Suddenly, while we were recapping some of our experiences to Lt. Cdr. Howell and Photographer's Mate Conger, a loud shrill scream pierced the fog and out of the water, clearing the top of the ice shelf with ease, came this huge Penguin. The surface of the ice shelf was a good two and a half feet above the water and this bird (if you can call him that!) must have been four feet tall. You can well imagine the tremendous speed he had attained to clear the shelf so easily. His forward momentum caused him to slide along on his belly for 10 to 15 feet before coming to a halt right in front of us (no more than eight feet away). He stuck his beak in the ice and pushed himself into an upright position. They do appear quite odd standing there on those big webbed feet that look as if they are stuck right on their buttocks. He cocked his head from side to side, and up and down really giving us the once over. I guess it was the first time he had ever seen anything as weird as us before. He then let out another scream which was immediately answered, and followed by, the speedy arrival of his buddy (or mate). They both stood there staring at us from every possible aspect. Of course we were just as inquisitive about them. Most of us had never seen or heard of penguins this huge. Someone commented they had read about a penguin this size, with an orange half moon on each side of it's neck, called an Emperor Penguin, and it was supposed to be the rarest bird in the world. These birds had to be emperors; they appeared so big and proud, and a sight to behold with their orange half moons! Their bodies were covered with a very heavy looking yellow oil, or grease, plainly visible in the white of their chest and belly coats. The Captain told me if I could capture one of them he would let me keep him on board the ship for a couple of days, so I started cautiously toward one of them (keeping between the bird and his escape route, the ocean!). When I was nearly close enough to grab him, he just tipped himself over on his belly and began sliding along on the ice by propelling his feet into the hard-packed snow. His speed was really quite slow, and I was staying with him on a fast walk. He must have felt the futility of his efforts because he stopped short, stood erect (once again with the beak in the snow to right himself), and looked me right in the eye. Noticing I was still coming toward him (within reaching distance now), he let loose with a very loud, annoyed, and totally irritated sounding screech. He stretched his little flipper (a penguin's wing) out as if to fend me off and I grabbed it. He promptly clamped down on my hand with his large, strong beak. Believe me, I am very grateful for the fact that it was not lined with teeth! His bluff worked, I released him immediately! The guys laughed uproariously, but I am confident they agreed with my decision to withdraw. Shortly after arriving at this rendezvous position, we decided to get Frenchie to the plane as soon as possible, fog or no fog! The fog was still extremely heavy but the radar gave the co-pilot a clear picture of his location in reference to the edge of the lake. Lt. Cdr. Howell informed the aircraft, with the aid of a megaphone, that we were bringing Frenchie out to the plane. The co-pilot was blipping the engines approximately 100 feet away, with both sea anchors streamed (sea anchors are water brakes, huge canvas, bucket shaped devices, with what would be the bottom removed, and a rope harness attached). It was far too deep to anchor; however, this condition kept the plane almost stopped.

The decision was made in Washington, D.C. that all the survivors would be returned to the United States immediately. Captain Caldwell managed, after much haggling with Washington, to stay in Command of his Ship. Warr and I were extremely disappointed as we had counted upon staying with the Ship, finishing up the operations, going around the Horn (a big deal for a Sailor), and pitching a big liberty in Rio de Janeiro on the way back.

We made our rendezvous with the USS PHILIPPINE SEA sometime around midnight. Plenty of daylight down there around the clock! This was to be our first experience with a "Boatswain's Chair". A Boatswain's Chair is a seat rigged on a pulley line tied between two ships. At sea this can be a very thrilling, and sometimes wet, ride. The line has to be kept as tight as possible, allowing for the slack and strain as the ships roll toward each other and then apart. The passenger may drop into the sea on one roll and then high in the air on the next (at this point, if the line is too tight, it will snap). They successfully transferred all of us. We were fortunate, none of us got wet! Credit must be given the crews handling the lines on each ship; they were really on the ball. Frenchie was strapped in a wire body stretcher and his transfer was also flawless. Now that we were aboard the USS PHILIPPINE SEA we knew we'd have to wait until Admiral Byrd's planes had been launched for Little America before we would be headed back to Panama. Far more important, however, was the fact that Frenchie was now under a good Doctor's / Surgeon's care. As soon as we were assigned bunks and a place to stow our gear, we (Warr and I) commenced to investigate this floating Naval Air Station! The first place we headed for was the Radio Shack. No one knew who we were so we introduced ourselves. They were glad to meet us and informed us they had been keeping up with our story on all the news reports. They let me contact the BROWNSON on CW (Morse Code) and I thanked all the guys on the USS BROWNSON for the wonderful care and manner in which they had treated us while we were on board. They asked us to remember them at the big conference in Washington, and I acknowledged. They wished us luck, and we wished them the same, and signed off. We then thanked the guys in the Radio Shack and told them we would be seeing them. We were notified that Frenchie was going to have both legs amputated. We had felt certain this would be inevitable, but it still came as a shock! Gangrene had started to travel up his legs and Doctor Barber felt the immediate operation was necessary in order to save as much of each knee joint as possible. All of us paid him a visit the night before the operation to remove the first leg. We thought we might be able to cheer him up, but we should have known, nothing could dampen Frenchie's spirit! In fact, he even told us a couple of good jokes. Up to his old tricks again! Always trying to keep us from worrying, no matter how dismal things looked for him. We were not allowed to see Frenchie again until after the operations were over, and the Doctor felt he was up to it. However, we kept in close contact through a Corpsman who was with him most of the time. The day after the first operation, Frenchie told them not to give him any more dope as it made him very ill. (I shuddered to think what I would be doing now, with one leg just removed and the other to be removed as soon as possible). But it didn't seem to bother Frenchie (although we knew it HAD to!) He told Dr. Barber,

Don't misunderstand this one very important fact, his legs were frozen solid before removal; this deadened any possibility of direct pain from the immediate area of the operation. Whether there were locals applied on top of the frozen area or not, I do not know. To further amplify the courage of this man, I would like to relate something to you as told to me by the Corpsman who was there; while the other leg was being removed, Frenchie had this Corpsman in hysterics with one joke after another. Of course a blind was up, keeping the operation from his vision, but I, for one, would have needed a lot more than that. It was not too much later, after Doctor Barber informed Frenchie that both operations were a complete success that Frenchie jokingly made some comment which included the words, "Just call me Shorty, Doc.". Doctor Barber and Frenchie are still the best of friends and there is a tremendous mutual admiration and respect between them. We rode the USS PHILIPPINE SEA back to Panama where we were met by a special Naval Delegate from Washington, D.C., who escorted us to the Naval Air Station, and aboard our special chartered flight to Washington. Frenchie, of course, had to remain in Dr. Barber's care on the Ship. He rode the ship back to the United States and was transferred to the Naval Hospital, Philadelphia, Pa. Upon arrival in Washington, we were rushed from the plane directly to a large conference room loaded with high ranking officials, as well as quite a few reporters. We were interrogated at length regarding our experiences, with particular emphasis directed to our survival problems. Subsequently, we were transferred to the Naval Receiving Station in Washington, D.C., where we were to remain until such time as the Navy felt they no longer needed our assistance in completing the required official reports. Shortly thereafter, we were authorized rest and rehabilitation leave. My family was in Prairieton, Indiana visiting my Aunt and Uncle on their farm. Prairieton is a small town just south of Terre Haute, Indiana. I purchased a train ticket to Terre Haute, called my parents and advised them I was on my way. With all the excitement of our arrival in Washington, crash survivors, heroes, etc., I was really riding high! Our first major stop was in Indianapolis. The Porter stated we had a few minutes to wait so I ran off the train to look for a telephone - right into the arms of my parents, Helen and Frank Robbins, and my sister, Barbara Jean Robbins. They decided to surprise me by meeting me in Indianapolis... they certainly were successful; I was stunned! Also on hand were a couple of reporters from the Indianapolis Star, flashing camera bulbs at us and, after a short interview, I retrieved my bag from the train and returned with my family to Prairieton. We have always been a very close family. This reunion was one of the high points in our lives. While in Prairieton, Dad gave me the family car, a six year old Plymouth in mint condition. This also gave him a good excuse to buy a new one there (much cheaper in Indiana than in our home State of California.) Now I was really a big shot, driving my own car back to Washington. I was caught in a snowstorm on the way and nearly totaled my newly acquired pride and joy. I could hardly wait to show my girl friend in Washington my new car. My girl friend, Dale Puckett, was the sweetest little girl I had ever known. I dated her quite regularly before going on OPERATION HIGHJUMP. I referred to her as my "fiancée". She was always an extremely busy little lady, holding down two jobs and going to college. She had been an orphan most of her life and, in fact, had spent many of her young years in an orphanage. She was the first girl whom I had met since starting my career in the Navy whose warmth, charm, and genuine sincerity, coupled with a sparkling personality (to say nothing of her fantastic figure!) kept me totally mesmerized!! My feelings today have only been enhanced by our 52 years of blissful married life. I wish every married couple could know the total happiness we continue to enjoy each and every year. Now, back to my story . . . . Upon returning to Washington, I learned Frenchie was now at the Naval Hospital in Philadelphia. I was anxious to see him again. I told Warr (my little buddy from the crash) I was going to drive up there to see Frenchie on the weekend. Warr was going that way also, on his way home. I telephoned Dale and asked her if she would like to meet Frenchie. She stated she had been looking forward to meeting him. I had told her all about him and felt confident she would like to go. So, Saturday morning, Warr and I drove by and picked up Dale. About half way to Philadelphia, Warr's homeward course detoured from ours. At this point, we wished him all the best and were on our way. We arrived in Philadelphia just before noon, and enjoyed a very nice lunch in an especially nice hotel restaurant. In fact, we liked the hotel so well that I had the Bell Captain set up a nice room for my fiancée, and another for me. After depositing our luggage in our respective rooms and freshening up a bit, we headed straight for the hospital. At the hospital, we were told where we could find Frenchie and just outside his room, I cautioned Dale about his looks and prepared her as best I could for what she was about to see. She assured me she would be all right and would never think of embarrassing Frenchie no matter what his condition. When we stepped through the door, his eyes lit up and the good side of his face was smiling. His good arm was propped close over his head for the purpose of grafting skin to one side of his face. His right eye was slightly popped in appearance, as the upper eyelid had been burned away. The odor of burned skin was still prevalent in the room. His mouth had been burned also and this factor, combined with his strong Cajun accent, made understanding him a bit difficult for Dale, but I was use to it. We were all so excited we found ourselves trying to jabber away at the same time. As always, his spirits were excellent. Like myself, Dale was in awe of this courageous, wonderful human being called Frenchie! We had not been in the room long and already Frenchie was expounding at great length to Dale about what a great guy I was, and how she should consider herself very fortunate to know such a fine fella! She stated she did, indeed, consider herself very fortunate to know such a fantastic guy as "her beloved Jim". I was a little embarrassed by all the plaudits, for I felt so fortunate to have so lovely a girl friend as Dale. She related to Frenchie all the many courageous things I had told her about him. Once again, Frenchie had us in stitches with a whole string of jokes, many of which were the things that had happened to him since he had been hospitalized. What a sense of humor the man possesses! We exchanged "sea stories" at great length, mostly for Dale's benefit, and she was hanging on to our every word! We enjoyed our afternoon with Frenchie thoroughly, and felt exhilarated by the fact that his spirits were so high. Upon departing, Dale assured Frenchie again that she did indeed consider herself very lucky to know me, and also that she would not do anything to hurt me - not ever! And me? Embarrassed again! We had a nice dinner, enjoyed a little sightseeing, a lot of dancing, and about midnight I said goodnight to Dale. On the way down to my room, I thanked God for saving this very special little lady just for me. I made up my mind right then that I was going to ask her to marry me. The following morning, we knew we had to immediately start the trip home. We drove by the hospital, chatted with Frenchie for a little while, and reluctantly said our good-bye's knowing that we were leaving with enough memories of this remarkable man to last us a lifetime, and headed back to Washington. Later, we learned that Frenchie was kept in the hospital for nearly a year longer than was necessary due to his ability to lift the spirits of veterans returning from Korea who were despondent about losing an arm or a leg, and had become completely withdrawn. A typical case in point: a Fighter Pilot, about to have his right leg amputated, refused to eat or talk to anybody. Frenchie was told of this and stated that he wanted to see him right away. He was wheelchaired to the pilot's bedside. Frenchie gave him a big "Hi, there!" The pilot looked over and became interested immediately; it is difficult to imagine what thoughts must have passed through his mind. Perhaps something like,

They exchanged yarns at length, and Frenchie even had the pilot laughing! Frenchie's dynamic personality, as well as his extremely high positive attitude, was always a great source of encouragement for everyone, especially those with serious problems. Frenchie was forever telling everyone that he was going to walk out of the hospital when they finally released him, and he did! He would get up in the middle of the night, slip into his newly acquired legs (wood, plastic, or whatever they were), and practice knee bends (and whatever else he could do), while holding on to the bed post. He would exercise in this manner until his stumps were raw and he could no longer stand the pain. Needless to say, with this type of determination it was not very long until he was walking on his own. Dale and I returned to Washington and our respective jobs. Shortly thereafter, we became Mr. and Mrs. (April 3, 1947) and, without question, that was the smartest move I ever made in my life! We were transferred to San Diego almost immediately, my hometown. Frenchie was medically retired and returned to his home in Breaux Bridge, Louisiana, a small suburb of Lafayette, Louisiana. Incidentally, Breaux Bridge is the "Crawfish Capitol of the World". He married his childhood sweetheart, built his own beautiful brick home, and settled down to raising a family (one of the most beautiful families we have ever had the pleasure to know.) Meanwhile, Dale and I completed my years to retirement in the Navy, which included tours in Bermuda, Hawaii, and Midway Island. I retired from the Navy in San Diego as a Chief Petty Officer in my hometown of birth, in May of 1965 after 22 years of a happy and wonderful career. By the way, I continued flying in PBM's until 1950, my faith in them and their pilots had not been shaken in the least by the crash (although, to this day, I still have nightmares that return to haunt me time and time again, and not for a moment have I forgotten the three shipmates who lost their lives in one of the world's most remote plane crashes.) We were blessed with one son, James E. Robbins. He and his wife, Marilyn, have a lovely home in Del Mar (in the North County, and a short distance from our home in San Diego), and we have two beautiful grandchildren, Bobby and Debbie and two great grandsons, Mark Oliver and Ethan Davies. I am presently residing in Palm Desert, CA, with my wonderful wife, Dale, and counting my blessings every day. ** I now am fully convinced that if it hadn't been for help from the "Greater Power", we would all still be down there. Also, the navy's Bureau of Missing Persons should be attempting to bring Lopez, Hendersin and Williams back for the full-dress Military Funeral they so richly deserve! ** Family information revised in July, 1999. The End

** In commemoration of the 50th Anniversary of Operation Highjump. The Stokes Collection released a special limited edition lithograph and a reproduction on canvas depicting the rescue of the crew of GEORGE ONE. For further information, please contact the Stokes Collection at P.O. Box 1420, Pebble Beach, CA 93953.

|