|

|

|

2104 from Academia Website

Göbekli Tepe is a name that will be familiar to anyone interested in the ancient mysteries subject.

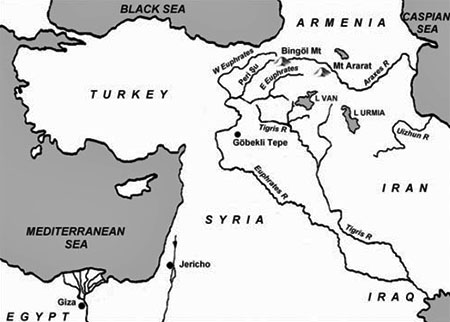

Billed as the oldest stone temple in the world, it is composed of a series of megalithic structures containing rings of beautifully carved T-shaped pillars. It sits on a mountain ridge at the western termination of the Ante-Taurus range in southeast Anatolia (today part of the Republic of Turkey), just eight miles (thirteen kilometers) from the ancient city of Urfa, Abraham’s traditional birthplace.

Here its secrets have remained hidden beneath an artificial, belly-shaped mound for the last ten thousand years.

Agriculture and animal husbandry were barely known when Göbekli Tepe was built, and roaming the fertile landscape of southwest Asia were, we are told, primitive hunter-gatherers, whose sole existence revolved around survival on a day-to-day basis.

So what is Göbekli Tepe? Who created it, and why?

More pressingly, why did its builders

bury their creation at the end of its useful life?

He was aware that a preliminary survey of Göbekli Tepe made in 1963 had concluded that the scattered fragments of cut and dressed limestone and broken pieces of sculpture found here were the product of a long forgotten Byzantine cemetery.

Yet when Schmidt arrived and saw not only the stone fragments, but also the thousands of stone tools littering the occupational mound, he concluded differently.

The mound, which is around 300 meters (330 yards) in length, 250 meters (275 yards) in breadth and 15 meters (50 feet) in height, belonged to an infinitely older age, one that thrived at the end of the Paleolithic age some eleven and a half thousand years ago.

He knew also that unless he walked away now, then he would be at Göbekli Tepe for the rest of his life. Thankfully Schmidt did decide to stay and excavate the site, for it was later discovered that the mountain ridge on which Göbekli Tepe sits was scheduled to become a quarry, its limestone rock to be used as foundation ballast for the new Urfa to Mardin highway.

Since 1995 Schmidt and his international

team of specialists, working on behalf of the German Archaeological

Institute and the Museum of Sanlıurfa (Urfa’s official title), have

uncovered four extraordinary stone structures at Göbekli Tepe,

constructed ca. 9500-8500 BC, along with a dozen or so smaller, and

often much simpler, rooms dating to ca. 8500-8000 BC.

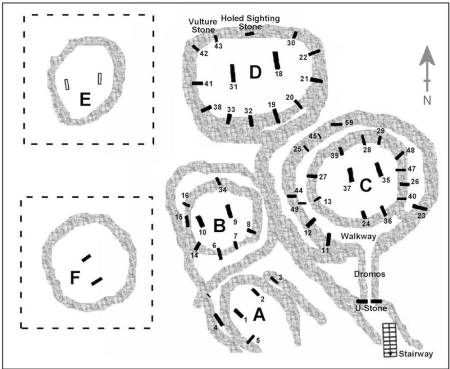

Elliptical in shape, and measuring between 15 and 20 meters (50 and 65 feet) in size, they each have rings of T-shaped standing stones - originally twelve in number - set within oval shaped walls made of quarry stones held in place by a thin layer of mortar (Enclosure C has an additional, and slightly later, inner ring of stones, as well as an approach passage or dromos entering from the south).

The pillars, which are all manufactured from limestone quarried from the mountain ridge, are very often adorned with carvings of strange creatures of the natural world, executed either in bas-relief or 3D sculpture.

Plan of GT’s main enclosures (Pic credit: Rodney Hale).

The stones are positioned like spokes of a wheel facing two much larger T-shaped monoliths, standing side-by-side at the centre of the enclosures, like twin portals to another world. In Enclosure C only the stumps of the central monoliths remain. Yet those in Enclosure D (see Fig. 2) are complete and rise to a height of 5.5 meters (18.5 feet).

Further examples of these twin central pillars are to be seen in Enclosure B, as well as in some of the younger structures uncovered at the site.

Bent arms are carved in relief on their wider, side faces. These terminate in hands with long, spindly fingers that curl around the pillar’s front narrow edge. Dropping vertically between the T-shaped "head" and the hands are twin vertical lines, indicating the hems of an open garment or stole of some kind.

Some T-shapes have a carved symbol on their "necks," above which is a V-shaped double line indicating that they are to be seen as pendants strung on cords, perhaps indicating devices of recognition, or emblems of office. They include bulls’ heads (bucrania), as well as H shapes, and also an eye cupped by a crescent.

Unique to the twin pillars in Enclosure D are wide belts with U-shaped belt buckles (see Fig. 3).

The twin central pillars in Enclosure D (Pic credit: Andrew Collins).

The belt on Enclosure D’s Pillar 18

(Pic credit: Andrew

Collins).

On top of this, the twelve-fold division of the stones in Enclosures C and D suggests a harmonisation with the celestial bodies, in particular the cycles of the sun and moon.

Did the Göbekli builders synchronize their monuments with the movements of the heavenly bodies?

In 2012 Robert Schoch, a geologist with the University of Boston, proposed that the twin central pillars in Enclosures B, C and D at Göbekli Tepe targeted the rising of the belt stars of Orion as they would have appeared on the horizon during the epoch of their construction.

As attractive as this proposal might seem - especially in view of Orion’s prominence in ancient astronomies - Schoch’s findings were dismissed by Italian astrophysicist and archaeoastronomer Giulio Magli of the University of Milan.

Having checked Göbekli Tepe’s relationship with Orion at this time, Magli discovered that for these alignments to work the megalithic enclosures would have to be at least a thousand years younger than any current dating estimates, which suggest a foundation date for the main enclosures somewhere in the region of ca. 9500-9000 BC.

The sudden appearance on the southern horizon of this bright star might, Magli proposed, have catalyzed the local hunter-gathering communities into building the first monumental architecture in human history.

It was another very attractive idea, and coming from an academic like Magli, it was destined to feature in scientific magazines, journals and websites worldwide.

But was it correct? Had Italy’s leading archaeo-astronomer found the true purpose behind the creation of Göbekli Tepe?

He determined that when Sirius first began to rise again around 9500 BC, the star only managed a feeble arc across the southern horizon before disappearing out of sight, a situation that barely changed for hundreds of years.

What is more, astronomy tells us that the nearer a star is to the horizon, the dimmer it will appear to the eye due to various natural factors, including atmospheric absorption and aerosol pollution.

These factors have established values, and when properly calculated for the latitude of Göbekli Tepe for 8950 BC and 9400 BC, the dates offered by Magli’s alignments for Enclosures C and D respectively, Sirius would have been barely visible as it passed low over the southern horizon (see Fig. 4).

Moreover, the low arc the star made each

night meant that it shifted its position against the local horizon

by as much as 3ş in just 20 minutes, making it a highly unsuitable

target to align monoliths toward with an estimated weight of around

fifteen tonnes a piece.

The faint star Sirius as it would have appeared rising on the southern horizon in 9400 BC.

Moreover, their existence should resonate with the beliefs and practices of the Epi-Paleolithic (that is, terminal Upper Paleolithic) peoples inhabiting the ancient world in the epoch immediately prior to the construction of Göbekli Tepe.

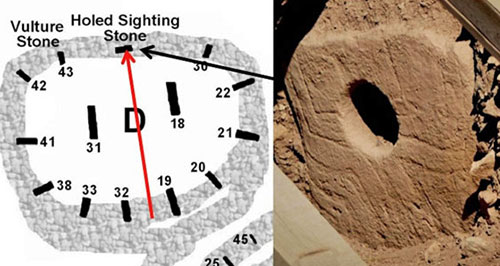

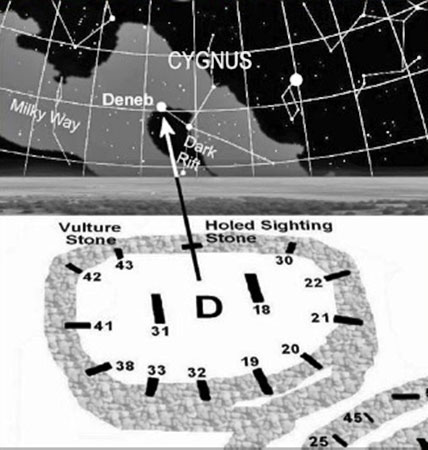

Yet there is every reason to believe that the structures are directed not southwards, towards Orion or Sirius, but north towards the circumpolar (i.e., never setting) and near circumpolar stars that forever turn about the celestial pole.

What is more, a person standing between the twin central pillars in Enclosures C and D at the proposed time of their construction, ca. 8980 and 9400 BC

Left, plan of Enclosure D showing position of holed stone and mean azimuth of the twin central pillars. Right, the holed stone in Enclosure D. (Pic Credits: Rodney Hale/Andrew Collins)

Enclosure D’s twin central pillars showing the position of the holed stone immediately behind them. (Pic credit: Andrew Collins)

This meant that if a person were to stand between the twin central pillars in these enclosures, they could have watched Deneb set through the circular apertures of the holed stones (Fig. 7).

The setting of Cygnus’s bright star Deneb aligned with the holed stone in Enclosure D. Not to scale. (Pic credit: Rodney Hale)

The answer lies in the fact that it marks the point on the Milky Way where it splits to form two separate streams, due to the presence of stellar dust and debris in line with the axis of the galactic plane. Ancient cultures saw this fork or cleft, known to astronomers as the Great Rift or Cygnus Rift, as an entrance to the sky-world, or upper world, existing beyond the physical realm, an idea that might well go back to Paleolithic times.

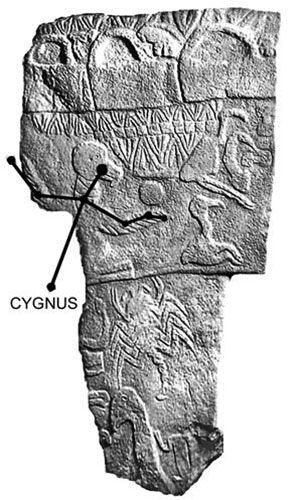

In 2000 Dr. Michael Rappenglück of the University of Munich examined the famous painted fresco of a bison and bird-headed man in the Lascaux cave system in southern France, executed ca. 16,500-15,000 BC (see Fig. 8).

He concluded that it depicts an abstract representation of the area of sky to which it faces, in particular the bright star Deneb in Cygnus.

Reconstruction of the enigmatic well scene in the Lascaux cave in France’s Dordogne region (Pic credit: Yuri Leitch).

It is a fact expressed, Rappenglück argued, in the image beneath the birdman of a bird on a pole.

Note: Pole stars change across the millennia due to the effects of precession. Today Polaris in Ursa Minor is Pole Star. Between 16,500 BC and 14,000 BC it was Deneb. Between ca. 14,000 and 13,000 BC it was the star Delta Cygni, and between ca. 13,000-11,000 BC it was Vega in Lyra. Thereafter there was no pole star for several thousand years, meaning that when Göbekli Tepe was built, ca. 9500-8000 BC, no star marked the celestial pole.

Arguably the bird on a stick at Lascaux shows the Cygnus constellation marking the position of the celestial pole, with the pole itself representing the so-called axis mundi, or axis of the earth. This is a place or location, usually a ritual or holy site, where the cosmic axis, the turning point of the heavens, was thought to be anchored to the ground.

As for the birdman next to the pole, he

is very likely a shaman ascending to the sky world during some kind

of ecstatic or altered state of consciousness.

Vulture Shamanism

Indeed, the vulture features prominently in the carved art of Göbekli Tepe and also at other Neolithic cult centers in Anatolia.

The reason for the bird’s prominence in the cult of the dead is its association with excarnation, the defleshing of human carcasses following death, something known to have been practiced in Anatolia during Neolithic times.

The soul of the individual, usually depicted as a ball-like head, is occasionally shown departing its material environment in the company of the vulture, acting in its capacity as a psychopomp, a Greek word meaning "soul carrier" or "soul accompanier."

Göbekli Tepe’s Vulture Stone (Pillar 43), with the Cygnus stars overlaid on its main vulture carving (Pic credit: Rodney Hale).

This act is shown on Göbekli Tepe’s Pillar 43, a.k.a the Vulture Stone, situated immediately to the left of the structure’s holed stone.

It shows the soul of a deceased person as a ball on the wing of a strange looking vulture with outstretched wings that bears a distinct likeness to the shape of the Cygnus constellation (see Fig. 9).

Vulture wings, some still articulated, unearthed at one early Neolithic site in southwest Asia indicate that shamans of this period adopted the guise of the vulture to perform ceremonies in which they would exit their physical environment and enter otherworldly realms.

Their sky-world, where the soul returned to in death and new souls emerged from prior to birth, was most likely seen to exist beyond the opening to the Milky Way’s Great Rift, marked by the star Deneb in Cygnus.

This, as we have seen, was synchronized at the moment of its setting with the apertures of the holed stones erected in Enclosures C and D at Göbekli Tepe.

Was it through the apertures in these stones that the shamans exited this world so that they might converse with power animals, ancestral spirits and celestial beings? Is this what the stone temples at Göbekli Tepe were - portals to the sky-world, quite literally star-gates?

If so, then what were these star portals used for, and by whom?

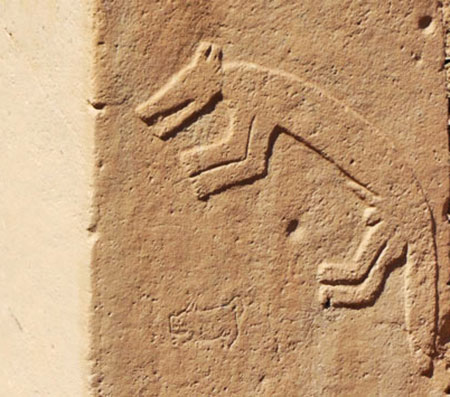

This is the fox. It is seen leaping across the inner faces of various of the twin central pillars in Enclosures A, B, C and D (see Fig. 10). In addition to this, the anthropomorphic twin monoliths at the centre of Enclosure D have fox-pelt loincloths carved in relief beneath their wide belts, as if the T-shapes are wearing them to cover their genitalia.

What is more, the high level of faunal remains belonging to the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) found at Göbekli Tepe led archaeozoologist Joris Peters, writing with Klaus Schmidt, to conclude that the interest in this creature went beyond any domestic usage and must be connected with the,

That this statement was made before the

discovery of the fox-pelt loincloths carved on the front narrow

faces of Enclosure D’s central pillars means that what Peters and

Schmidt go on to say in the same paper should not be ignored, for in

their opinion this evidence suggests "a specific worship of foxes

may be reflected here."

Leaping fox bas-relief on the inner face of Enclosure B’s Pillar 10 (Pic credit: Andrew Collins).

In various parts of the ancient world the fox, or more correctly the fox’s tail, has been identified with the appearance of comets (a three- pronged comet-like symbol appears on the belt buckle worn by one of the twin monolith in Enclosure D, directly above the fox-pelt loincloth - see Fig. 11).

Foxes are seen as manifestations of a supernatural creature in the form of a trickster, and when not a fox, this same mythical creature is most often identified with the wolf.

In Norse mythology the trickster is the Fenris wolf. With its fierce lupine offspring, Fenris wreaks havoc at Ragnarok, the Doom of the Gods, a kind of pagan Armageddon where even the gods die trying to save the world during an almighty cataclysm involving fire, flood and ice.

As early as 1884 US congressman and catastrophe writer Ignatius Donnelly (1831-1901) proposed in his book Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel, that the Fenris wolf and other supernatural canids featured in the Ragnarok account are abstract memories of a series of comet impacts that devastated the planet towards the end of the last great glacial age.

The suspected comet symbol occupying the position of the belt buckle on Enclosure D’s eastern central monolith (Pillar 18), showing also the fox-pelt loincloth, possibly indicating comet symbolism (Pic credit: Andrew Collins).

They occur right across Europe, and are found also in the sacred writings of Zoroastrianism, a religious doctrine that once thrived in Iran, India, and Armenia.

In a holy book entitled the Bundahishn it states:

Gokihar is generally translated as

"meteor," that is, a comet, asteroid, or bolide of some sort, while

the name itself has been interpreted as meaning "wolf progeny."

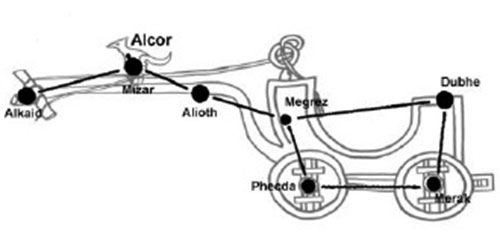

In many ancient societies epoch-shattering cataclysms were often seen to have been caused or triggered by the actions of supernatural sky-creatures - cosmic tricksters ever ready to attack the axis mundi, the world axis or sky-pole, and as a consequence bring about the destruction of the world. Usually, the daily turning of the axis was imagined as being undertaken by further cosmic creatures, most commonly oxen pulling a plough or wain.

They are imagined as circling around the celestial pole to which they were tethered, causing the stars to revolve about the heavens.

The Plough or Big Dipper constellation, which forms part of Ursa Major, the great bear, as a celestial wain, showing the position of Alcor, the Fox Star or Wolf Star (Pic credit: Andrew Collins/Storm Constantine/Rodney Hale).

One of its stars, the tiny Alcor, which lies close to a larger star named Mizar, is identified with the cosmic trickster, and even bears the name Fox Star or Wolf Star in various ancient astronomies (see Fig. 12).

It was seen as a visible reminder of the sky-wolf or sky-fox who constantly tries to attack and bring down the sky-pole holding up the heavens.

Therefore it was of paramount importance among ancient cultures, particularly in Europe, to protect the cosmic axis from the mischievous actions of the trickster, as catastrophic events like Ragnarok were not simply events that happened in the past.

They were seen as the once and future fate of

the world.

So to find similar evidence emerging from Göbekli Tepe of ritual activity involving the fox should not be ignored.

Geological, archaeological and paleo-climatological records reveal the terrifying consequences of this proposed cataclysm, which caused super-tsunamis, mass flooding, severe wildfires, and a subsequent period of darkness, believed to have triggered a 1,300-year mini ice age known as the Younger Dryas event.

Did a comet impact with the earth around 12,900 years ago? Did its aftermath result in the construction of GT? (Pic credit: USGC)

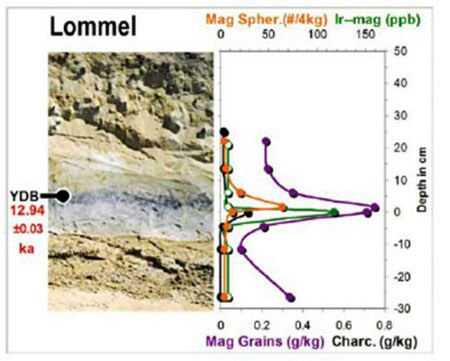

From Belgium across to Belarus, and from Egypt all the way down to Australia, an eight-centimeter (three-inch) thick layer of ash and fire debris is present in the geological record corresponding to a date of approximately 12,900 years ago.

Known as the Usselo horizon (see Fig. 14), it has been found to contain microscopic evidence of an impact scenario, including magnetic spherules and nano-diamonds.

These are usually created during extremely high temperature aerial blasts, triggered in this instance by disintegrating comet fragments.

What is more, compelling evidence of a close-proximity air blast at this same time has been found at an Epi-Paleolithic settlement site named Abu Hureyra, just 100 miles (160 kilometers) from Göbekli Tepe, showing that southwest Asia did not escape the devastation.

The eight-centimetre (three-inch) Usselo Horizon. This example of the boundary layer was found at Lommel, Belgium, and dated at 12,940 years ago. The same ash-rich layer has been found at sites all over the world (Pic credit: Johán B. Kloosterman).

Well, the fact of the matter is that the Younger Dryas Boundary impact event, its official title among the scientific community, was not a lone event that took place on a single day.

Ice core samples from Greenland indicate that following the initial event in around 10,900 BC, the northern hemisphere experienced incessant wildfires for hundreds of years afterwards, culminating with another spike of activity around 10,340 BC.

Dr. Richard Firestone of Lawrence

Berkeley National Laboratory of Nuclear Science and his co-authors

in their book The Cycle of Cosmic Catastrophes (2006), which sets

out the full extent of the Younger Dryas impact event, believes that

10,340 BC "may be the date of one of the impacts."

If this was the case, then we can say with some certainty that one of the principal purposes behind its construction was to enable shamans to enter the sky-world and curtail the baleful actions of the cosmic trickster, which if not kept in check might well have brought about the destruction of the world.

Yet even assuming these ideas are correct,

Answers can, most likely, be found in the presence of the anthropomorphic pillars set in circles around the twin central pillars in the various enclosures.

Clearly, they have human form and may thus be seen as highly abstract statues. Schmidt has called them the first gods, celestial beings, and divine ancestors, but why do they have hammer-shaped heads? The front protrusion might easily represent an elongated face and jaw line, but what about the rear extension. What does this represent?

At Kilisik, near the town of Adıyaman in southeast Anatolia, just over 50 miles (80 kilometers) away from Göbekli Tepe, a mini T-shaped figure was found in 1965 (see Fig. 15).

Unlike the larger, more abstract T-shaped pillars found at Göbekli Tepe, this particular example, which dates to the same age, gives a more realistic impression of what it is meant to signify.

And suddenly it becomes clear that the extension at the back of the head is in fact a hood or headdress of some sort.

With this knowledge other stone figurines with extended heads found at Pre-Pottery Neolithic sites elsewhere in the region can also now be re-examined, and these too suggest that some kind of hood is being worn by the figure in question.

These hooded figures bear all the hallmarks of a ruling elite behind the construction at the site.

Fig. 15. The T-shaped statue found at Kilisik, near the town of Adıyaman in southeast Turkey, and thought to be contemporary with the construction phases at Göbekli Tepe. Note the hood-like extension to the rear of the head. (Pic credit: Gaziantep Museum)

The mini ice age triggered by the cataclysm not only caused a drop in temperature in areas affected by the cold spell, but also brought about long-lasting droughts in regions beyond the extent of the ice, including southwest Asia.

This would have resulted in the drying up of springs, streams and river sources, and the disappearance of herd animals seen as essential to the survival of Paleolithic hunter-gatherer societies across the Eurasian continent.

Hunting groups would have travelled hundreds, if not thousands, of miles to find new territories, where sufficient numbers of herd animals and adequate food and water supplies, might be found to sustain their communities.

As can be imagined, this would have resulted in territorial skirmishes and even fierce battles, leading to some populations either being annihilated or taken over by incoming groups, who would have seized the opportunity to exploit human populations and natural resources.

Not only did she uncover evidence of widescale bloodshed and violence across Europe and western Asia at this time, but she also noticed the footprints (see Fig. 16) of a very specific group of reindeer hunters reaching all the way from the Carpathian Mountains in Central Europe across to the Crimean Mountains, north of the Black Sea in what is today the Ukraine, a distance of some 850 miles (1,400 kilometers).

This easterly migration she saw as hunting groups exploring foreign territories, looking to exploit new resources now that the precious reindeer herds had disappeared into the arctic regions far to the north.

These reindeer hunters are known as the Swiderians, after the "type site" where their cultural traits were first recognized at Swidry Wielkie in Otwock, near Warsaw, in Poland.

Not only were they an advanced hunting society, with a unique stone tool technology, but the Swiderians also established sophisticated mining operations, some of the only accepted examples from the Paleolithic age, within the Swietokrzyskie (Holy Cross) Mountains of central Poland. Here they extracted "exotic" forms of flint, as well as hematite, used as ochre.

Long distance trading routes were established to transport stone tools and pre-form cores across hundreds of miles. Thus there is little question that the Swiderians were among the first miners anywhere in the world.

More importantly, they walked the earth both during and in the aftermath of the proposed Younger Dryas impact event.

Map showing the distribution of Swiderian tanged points found in Central and Eastern Europe during the tenth and eleventh millennia BC.

This they procured from find sites in the Carpathian Mountains, where even today obsidian is considered a magical substance, born of the sky and embodying the power of fire itself; it also happens to be one of the sharpest substances on earth.

The Epi-Paleolithic communities existing in eastern Anatolia during the Younger Dryas cold spell also coveted obsidian for making tools and projectile points.

This they obtained from key find sites close to a volcano named Nemrut Dag on the shores of Lake Van, Turkey’s largest inland sea, and in the foothills surrounding Bingöl Mountain, located in the nearby Armenian Highlands.

Tools and points made from obsidian deriving from these locations have been found in great quantities at proto- Neolithic sites in eastern Anatolia, seen as precursors to Göbekli Tepe.

Both in style and the manner of production they bear close similarities to the toolkit of the Swiderians, who are known to have reached as far east as the Caucasus Mountains, where they would have come up against indigenous peoples, most likely members of another advanced society known as the Zarzians, who almost certainly controlled the local obsidian trade at this time.

It seems likely that Swiderian groups continued southward, reaching eventually the obsidian find sites around Bingöl Mountain and Lake Van.

This would have brought them within easy reach of the late Palaeolithic and early Neolithic communities of southeast Anatolia (even Klaus Schmidt himself has compared the hunting strategies of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic peoples of southeast Anatolia with those of the Swiderians of the East European Plain).

They thrived in Western Europe between ca. 25,000-16,500 years ago, and developed an extraordinary stone blade technology. They were also responsible for some of the earliest ice age art in Western Europe, including the bison and birdman fresco in France’s Lascaux Cave.

The Solutreans came, most likely, from Central Europe, and were connected to another advanced population - that of the Eastern Gravettians, who thrived in highly advanced settlements in both Central Europe and on the Russian Plain between 30,000 and 20,000 BC.

They built communal buildings,

experimented with cereal farming as much as 30,000 years ago;

introduced the Mother Goddess cult, expressed in the production of

full-bodied Venus figurines; wore tailored clothes, sewn together

using bone needles, and revered both the wolf and arctic fox, which

would seem to have been associated with the soul’s journey into the

afterlife.

Fig. 17. On the left a Solutrean lance head around 20,000 years old, and on the right a Swiderian point fashioned from chocolate flint, around 11,000 years old. Not to scale. (Pic credits: J. L. Katzman/Aggsbach Paleolithic Blog).

They were tall, with large,

dolichocephalic (that is, elongated) heads, long faces, high

cheekbones, and strong jaws. Very likely, they derived not only from

the Cro-Magnons, the earliest anatomically modern humans to enter

Europe some forty-three thousand years ago, but also from another

human type known to have existed in Central Europe around

twenty-five thousand years ago.

Other examples were found in 1894 alongside wolf skulls at another Gravettian site unearthed at Predmostí, also in Moravia.

The Brünn type humans were tall with large, elongated skulls, long faces, strong brow ridges, and other striking features. Anthropologists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries found firm evidence that the Solutreans were linked to the Brünn population.

Moreover, that these suspected ancestors of the Solutreans had migrated to Central Europe from the Russian Plain, where advanced Gravettian settlements have been unearthed, some of which have produced human remains comparable with those of the Brünn type.

If the Swiderians did derive physiological traits from the Brünn population, then it is possible that both gained at least part of their unique physiognomy and technical skills from the Neanderthals, humanity’s closest cousins, whose communities lingered on in Eastern Europe until around 30,000 to 40,000 years ago.

In fact, Swiderian physiognomy was linked with the concept of Neanderthal hybrids as early as 1956, following the discovery of two human crania, one in Lithuania and another in Central Russia, which show Neanderthal-hybrid traits, and yet are attributable to the Swiderian population.

Further confirmation has come from the discovery of skeletal remains belonging to a Post-Swiderian culture, which have been compared with those of the Brünn population, who were themselves most probably Neanderthal-human hybrids.

Is it the memory of their great ancestors, who might have included Solutreans, Gravettians and even Neanderthal-human hybrids, that is enshrined in the twelvefold rings of T-shaped pillars found in key enclosures?

It was the Swiderian elite who most likely introduced the manner in which the hunter-gatherer populations of southeast Anatolia could alleviate their catastrophobia, the fear of further cataclysms in the wake of the Younger Dryas impact event.

These individuals, and their

descendants, probably controlled and managed the various phases of

building activity at Göbekli Tepe, something that led eventually to

the introduction of animal husbandry and agriculture across the

region, marking the earliest stages of the Neolithic revolution.

Old enclosures were periodically decommissioned, deconsecrated and covered over, quite literally "killed," at the end of their useful lives. New structures were built to replace them, but as time went by they became gradually smaller and more simpler in construction, until eventually they were no bigger than a family-sized Jacuzzi with pillars no more than one and a half meters (five feet) in height.

Somehow the world had changed, and the impetus for creating gigantic stone temples with monoliths as much as five and a half meters high was no longer there.

Sometime around 8000 BC the last remaining enclosures were covered over with earth and refuse matter, and the site abandoned to the elements.

All that remained was an

enormous belly-shaped mound that became an ideal expression of the

fact that the stone enclosures had originally been seen, not just as

star portals to another world, but also as womb-like chambers, where

the souls of shaman, or indeed the spirits of the dead,

Like their predecessors, they gained control of the all-important obsidian trade from find sites such as Bingol Mountain and Nemrut Dag, close to Lake Van. Their elites, who would appear to have belonged to specific family groups, artificially deformed their already elongated heads.

It is very possibly these ancestors who are depicted as the snake- or reptilian-headed figurines found in Ubaid cemeteries (see Fig. 18).

Snake-headed figurines found in Ubaid graves, ca. 5000-4100 BC. Now in the British Museum.

Their scribes preserved in cuneiform writing the ruling dynasties’ mythical history, in which the founders of the Neolithic revolution are named as the Anunnaki, the gods of heaven and earth.

Their birthplace was said to have been the Duku, a primeval mound located on the summit of a world mountain called Kharsag, or Hursag.

Here the Anunnaki gave humanity the first sheep and grain, which we can see as a memory of the introduction of animal husbandry and agriculture at the time of the Neolithic revolution.

The Anunnaki are occasionally likened to serpents, reflecting the snake-like physiognomy of the ruling elite of the earlier Halaf and Ubaid cultures.

Their oral traditions would one day be carried into the land of Canaan by the first Israelites and recorded down in religious works such as the Book of Enoch and the Book of Giants.

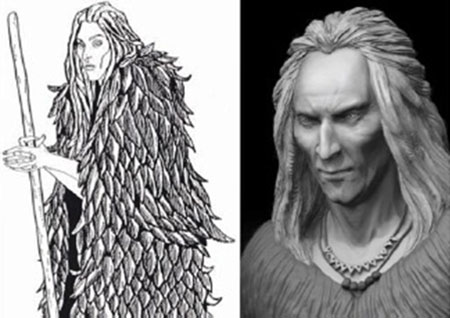

In these so-called Enochian texts the prime movers behind the construction of Göbekli Tepe, and the subsequent Neolithic revolution, are described as tall, pale-looking human angels called Watchers (see Fig. 19 & 20), who wear feather coats, have visages like vipers (that is, they have long facial features), and are occasionally described as Serpents (indeed, one Watcher is named as the Serpent that beguiled Eve in the Garden of Eden).

Left, a Watcher by artist Billie Walker John drawn in 1995, based on descriptions offered in Enochian material. Right, artist Russell M. Hossain’s 3D sculpt based on Billie Walker John’s original

(Pic credits: left,

Billie Walker John/Andrew Collins & right, Russell M. Hossain).

According to the book of Enoch, the rebel Watchers revealed to their wives the secret arts of heaven, many of which correspond pretty well with a number of firsts for humanity that took place in southwest Asia in the wake of the Neolithic revolution.

Are the Watchers a memory of the appearance in Anatolia of the Swiderians, whose striking appearance fits the description of the Watchers?

If so, then does it suggest that the strange appearance of the Watchers, with their long serpentine faces, might in part be due to them being Neanderthal-human hybrids (see Fig. 21)?

3D sculpts showing a Swiderian male and female by artist Russell M. Hossain based on available anatomical evidence. Are these the faces of the elite who inspired the creation of Göbekli Tepe, as well as the Watchers and Anunnaki of myth and legend? Do they show also Neanderthal-human hybrids? (Pic credit: Russell M. Hossain)

According to the book of Genesis this was located, in geographical terms, where the four rivers of Paradise took their course. Three of these rivers are easily determined. They are the Euphrates, the Tigris and the Araxes (the biblical Gihon), which all rise either in the mountains south of Lake Van or nearby in the Armenian Highlands.

What is more, two of the rivers, the Euphrates and Araxes, are seen to take their rise in the same vicinity - on the slopes of Bingöl Mountain, one of the primary sources of obsidian located around 200 miles (322 kilometers) from Göbekli Tepe (see Fig. 22).

Local tradition asserts that Bingöl was also the source of the fourth river of Paradise, the Pison, while ancient writers recorded that the true source of the Tigris was also in the Armenian Highlands.

This then was the true geographical location of Paradise.

This is Mount al-Judi, the modern Cudi Dag, which rises above the town of Cizre in southeast Anatolia, and not Mount Ararat further north in Armenia, which only received its status as "Place of Descent" in the fifth century AD.

In Muslim, Syriac and Kurdish tradition, the true Place of Descent is Mount al-Judi.

It is here that Noah and his family began the process of repopulating the world after the deluge that nearly destroyed the human race.

Map of eastern Turkey showing the principal rivers identified with the four rivers of Paradise.

In the centuries following the death of Jesus they believed that Seth’s "seed", which included the antediluvian patriarchs of the book of Genesis, were the only true and righteous descendants of Adam, and the inheritors of his divine wisdom.

Sethian writings, such as the various tracts found in a cave at Nag Hammadi in Egypt in 1945, speak repeatedly of the secrets of Adam being passed to Seth before his father’s death. Seth is said to have recorded them either in book form, or on tablets or pillars called stelae.

These were hidden in or on a holy mountain, existing in the vicinity of Paradise, so that they might survive a coming cataclysm of fire and flood.

Called variously Charaxio, Seir, or Sir, this mountain is linked in early Christian tradition with the site inhabited by the generations of Adam following the expulsion of the first couple from Paradise.

This is the quest I embark upon in the second half of Göbekli Tepe: Genesis of the Gods, with the result being the discovery in the Eastern Taurus Mountains of a forgotten Armenian monastery overlooking the traditional site of the Garden of Eden.

Before its destruction at the time of the Armenian genocide of 1915, the monks here preserved archaic traditions concerning the Garden of Eden and the existence of a holy relic of incredible religious significance.

Confirmation of the presence of this

holy relic at the monastery (which in the seventh century was given

a special decree of immunity from attack signed by the prophet

Mohammed himself) reveals what could be Adam’s ultimate secret - the

manner in which we as mortals may re-enter Paradise and become, as

once we were, like angels ourselves.

|