|

3 - Traces Of The Gods In China, Too

The China Airlines Boeing had taken off from Singapore an hour

behind schedule and had only made up half an hour when it landed in

Taipeh at 1530 hours. And I had arranged a meeting with Mr. Chiang

Fu-Tsung, Director of the National Palace Museum, for 1700 hours. I

left my luggage at the Ambassador Hotel in Nanking East Road, hailed

a taxi, got in next to the friendly, laughing driver and said:

“To

the National Palace Museum, please.”

The skinny little Buddha next

to me smiled, but I had a strong feeling that He had not understood

what I said. As he drove along at breakneck speed, I described my

destination in all the languages I knew. My Buddha nodded

indulgently, put his foot on the accelerator and finally

stopped-outside the railway station! He whipped open the door

smartly and with a radiant smile pointed to the station, which was

obviously not the museum I was looking for.

If only I had known a

few words of Chinese! I went into the main hall and suddenly I had a

brainwave. In the middle of it there was a bookstall with hundreds

of postcards on sale showing all the interesting buildings in Taipeh

and Taiwan. I bought postcards of all the places I intended to visit

during the next few days. My Buddha nodded earnestly when I showed

him the beautiful museum building and drove back the same way we had

come.

The museum was quite close to my hotel! (Fig. 31)

Fig. 31.

With the help of a picture post-card my skinny Buddha

drove

me to the lovely Palace Museum in Taipeh to meet Mr. Chiang Fu-Tsung.

I knew that there would be no language difficulties with Mr. Chiang

Fu-Tsung,

who had studied in Berlin and spoke German.

I had been told this by Mr. Chi, proprietor of the best Chinese

restaurant I have ever eaten in, the Lu- Taipeh in Lucerne. Mr. Chi

spent most of his life as chef to Chiang Kai-Shek, before he decided

to become a restaurateur in Switzerland. My friend Chi knew that I

was obsessed with the desire to find out as much as I could about

the mysterious finds at Baian Kara Ula.

That was the site in the

Sino-Tibetan frontier zone where the Chinese archaeologist Chi Pu

Tei found 716 granite plates in 1938. They were 2 centimeters thick,

with a hole exactly in the center from which a double-tracked

grooved script ran out spirally to the edge of the plate. In fact

they were rather like our long playing records. Brilliant scholars

puzzled for years over the secret of the stone plates until

Professor Tsum Urn Nui of the Academy of Prehistory, Peking,

succeeded in deciphering part of the grooved scripts in 1962.

Geological analysis showed a considerable cobalt and metal content;

physicists established that all the plates had a high vibration

rhythm, which led to the conclusion that they had been exposed to

high electrical tensions at some time. The finds at Baian Kara Ula

became a sensation when the Russian philologist Dr. Vyacheslav

Saizev published some de-ciphered texts of the stone plates.

They

related that 12,000 years ago members of an alien people landed on

the third planet, but their aircraft no longer had enough power to

take off from that distant world. I have established these proven

facts in detail in Gods from Outer Space. But the reason for my

journey to Taiwan was that the news published in Moscow, the

scholar’s full report on the stone plates, was deposited both in the

Peking Academy and the Historical Archives at Taipeh.

Thanks to a letter from my friend Chi, I had an appointment on this

cold, wet January afternoon with the Director of the Palace Museum,

who had confirmed our meeting in a courteous letter before I had

even started on my third journey round the world.

Fig. 32.

I had several productive and interesting conversations

with

Mr. Chiang Fu-Tsung, the Director of the Palace Museum.

The chances of my getting on the track of the stone plates in the

Palace Museum seemed very good.

The precious collection, with more than 250,000 cataloged items, had

been moved from its original

home in Peking on several occasions during the last 60 years. In

1913, during the uprising of the Kuomintang Party, in 1918, during

the Civil War, in 1937, during the war with the Japanese, who

occupied Peking, and in 1947, when Mao Tse Tung founded the People’s

Republic of China with the People’s Army of Liberation and made

Peking the capital again. Since 1947 the art treasures have been

stored in Taipeh.

A decorative visiting card on which Mr. Chi had written greetings

and recommendations to his friend Chiang Fu Tsung with a fine brush

made smiling men in uniform silently open all doors till we reached

the Director’s office. He greeted me in German-only when I

apologized for being late did he wave my excuses away with a long

sentence in Chinese. (Fig. 32.)

“You are a friend of my friend, you

are my friend. Welcome to China. What can I do for you?” he asked.

As we approached a low table, he gave an order aloud-to whom? Even

before we could sit down, museum guards brought paper-thin porcelain

cups and a decorated pot full of herb tea. The Director filled our

cups.

I went straight to the point and said that I was interested in the

Baian Kara Ula finds and that I should like to see the scholar’s

report on the stone plates that was here in Taipeh. My enthusiasm

was dampened when Mr. Chiang explained that this extensive report

had not shared the Museum’s odyssey, but was still preserved in the

Peking Academy, with which he had no contact. He noticed my intense

disappointment, but could give me very little consolation with the

rest of his information.

“I know about your efforts. They delve

deeply into the prehistory of peoples. I can only help with our

primeval ancestor Sinanthropus, who was discovered in 1927 in the

valley of Choukoutien, 25 miles southwest of Peking. In the opinion

of the anthropologists, this Sinanthropus Pekinensis, Peking Man, is

similar to homo Heidelbergtensis, but in any case resembles the

Chinese race, as it exists today in 800,000,000 examples. Peking Man

is supposed to come from the Middle Pleistocene, i.e. to be about

400,000 years old. After that there is really no more prehistory.”

The Director explained that there was no further evidence of

Neolithic cultures in North China until the third millennium B.C.

when the Yang-Shao culture on the Huang Ho produced painted ribbon

pottery. About the second millennium B.C. came the Ma-Shang culture,

the black pottery culture and the stone and copper culture of Sheng

Tse Ai of Shantung, followed by the luxuriant decoration which came

in with the beginning of the Bronze Age with the t’ao t’ieh, or

monster mask, and Li Wen with its broken right-angled

representations of thunder.

From the fifteenth to the eleventh

centuries there was a highly developed script with more than 2,000

pictographic and symbolic characters which were used for oracular

inscriptions.

In all periods, it was the task of Chinese rulers, the

“Sons of Heaven,” to see that the course of nature unfolded in an

orderly manner.

“As far as I know, for I am not a pre-historian, there is nothing in

the Middle Kingdom to lend wings to your special fantasy, no stone

axes, no primitive tools, not even traces of cave paintings. And the

oldest inscribed^ bones were dated to 3000 B.C.”

“What was on the bones?”

“So far it has proved impossible to decipher the inscriptions.”

“Isn’t there anything else?”

“A single vase that was excavated at An-yang near Honan. It was

dated to 2800 B.C.”

“Excuse me, Mr. Chian, but surely China must

have some evidence of its prehistory. There must be something to

show the development from the pre-historical to the historical

period. Are there no mysterious ruins, no crumbled cyclopean walls?”

“Our Chinese history can be traced back without a gap to the Emperor

Huang Ti and he lived in 2698 B.C. It is a known fact that the

compass existed as early as that. Therefore time cannot have begun

with Huang Ti! But what happened before him, my dear friend, lies in

the stars.”

“What do you mean, in the stars?”

Was there a tidbit left for me in this conversation after all? There

was. Mr. Chiang smiled:

“From the very earliest times the dragon has always been the Chinese

symbol of divinity, inaccessibility and invincibility. P’an Ku (Fig.

33) is the legendary name of the constructor of the Chinese

universe. He created the earth out of granite blocks which he caused

to fly down out of the cosmos. He divided up the waters and made a

gigantic .hole in the sky. He divided the sky into the eastern and

western hemispheres.”

“Might he have been a’ heavenly regent, who appeared in the

firmament in a spaceship?”

“No, my friend, the legend says nothing

about spaceships, it only mentions dragons, but it describes Fan Ku

as he who mastered chaos in the universe. He created the Yin Yang,

the conception of the dual forces in nature. Yang stands for male

power and the heavens, Yin for female beauty and the earth.

Everything that happens in the cosmos or on earth is subordinate to

one of these two symbols, which have penetrated deeply into Chinese

cosmological philosophy.”

Fig. 33.

Chinese brush drawing of the God P’an Ku, legendary master

of chaos and constructor of the Chinese universe.

He is supposed to

have built the world out of granite blocks that flew down from

space.

According to legend, every ruler and “Son of Heaven” is supposed to

have lived for 18,000 terrestrial years and if we take this estimate

at its face value, Fan Ku brought order into the heavens 2,229,000

years ago! Perhaps these astronomical calculations may be a few

years out here and there, but what does it matter with such a family

tree?

Fan Ku, whose legend is said to have spread throughout China, was

depicted differently in different regions, which is not surprising

in view of the vast size of this country with its surface area of

3,800,000 square miles. Sometimes he is a being with two horns on

his head and a hammer in his right hand, sometimes he appears as a

dragon mastering the four elements, sometimes he holds the 3 sun in

one hand and the moon in the other, some-times he is chipping away

at a rock-face, watched by a snake.

Actually, the Fan Ku legend in China is probably not so old as the

mighty man himself. Travelers from the kingdom of Siam (Thailand)

are reputed to have brought the legend to China for the first time

in the sixth century.

“Chinese mythology describes Yan Shih Tien-Tsun as the ‘father of

things,’” said the Director.

“He is

the unfathomable being, the beginning and end of all things, the

highest and most inconceivable being

in heaven. In later times he was also called Yu Ch’ing. If you write

about him, you must take care not

to confuse Yu Ch’ing with the mysterious Emperor Yu, who is reputed

to have caused the Flood. Do you know the legend of Yuan Shih Tien

Wang?”

I shook my head. The Director took a volume of the Dictionary of

Chinese Mythology from his shelves.

“There, read the story in your hotel. You will find some stories in

the dictionary that are fascinating when considered in connection

with your theories. For example, the legend of the goddess Chih Nu

who was the patron saint of weavers. While she was still young, her

father sent her to a neighbor who kept watch over the ‘Silver Stream

of the Heavens,’ obviously the Milky Way. Chih Nu grew up and became

very beautiful. She spent the days and nights playing and laughing,

never was there a wilder or crazier lover in heaven than Chih Nu.

The Sun King grew tired of these goings-on and when she bore a child

to her guardian friend, he ordered the ardent lover to take up his

post at the other end of the Silver Stream and only to see the

lovely Chih Nu once a year on the seventh night of the seventh

month.”

“The story of the king’s ^children who could not meet each other!”

“The legend has a happy ending for the lovers. Millions of shining

heavenly birds formed an endless bridge over the Milky Way. So Chih

Nu and her guardian could meet whenever they wanted.”

“If the

shining heavenly birds were really spaceships patrolling between the

stars, it seems perfectly plausible for the lovers to have met as

often as they wished.”

Mr. Chiang Fu-Tsung stood up:

“You are a visionary! But of course you’re not forced to kowtow to

traditional explanations. Perhaps modern interpretations of myths

and legends are justified, perhaps they will throw new light on

things. There is a lot we don’t know yet.”

The Director appointed the best-informed member of his staff,

Marshal P. S. Wu, Head of the Excavation Department, to act as my

guide during my stay. Although only a fraction of the 250,000 items

in the Museum are on display at any one time, there is still such a

bewilderingly large number that I could scarcely have collected my

“finds” without the help of Mr. Wu who understood instinctively what

interested me.

Here is a selection:

Bronze vessels from the period of the Shang dynasty (1766-1122 B.C.)

automatically reminded me of the other side of the Pacific. Nazca

pottery, pre-Inca work much more recent than the Chinese vessels,

exhibits very similar ornaments: geometrical lines, opposed squares

and spirals. A jade axe, a small copy of a larger one. The divine

symbol of the dragon with a trail of fire is engraved on the

greenish stone; the firmament is decorated with spheres. I

remembered identical representations on Assyrian cylinder seals.

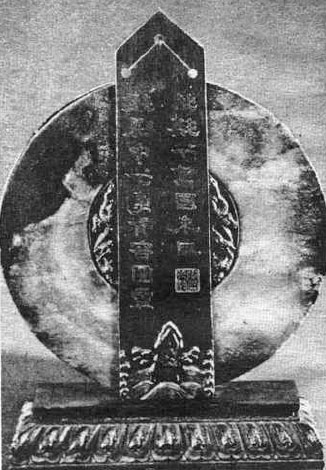

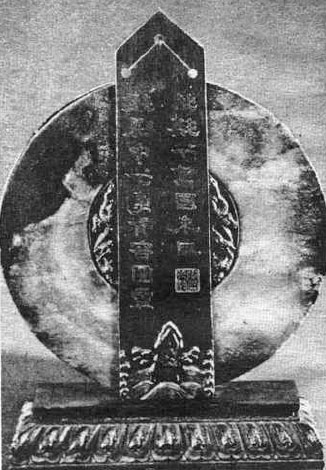

Fig. 34.

The jade discs have a hole in the middle and often sharp

points like

those on toothed wheels round the circumference. Were

they made from models?

Altar trappings for the worship of the god of the mountains and

clouds is the orthodox archaeological label under a right-angled

object dating to 206 B.C. A mountain is visible, but it is dwarfed

by a giant sphere with a trail of fire. This sphere, which has three

small spheres arranged geometrically above it, is so big that it

seems to be quite unrelated to sun, moon and stars. Altar trappings?

It is far more likely that in the remote past this picture recalled

some unforgettable, incomprehensible phenomenon in the sky.

Jade discs (Fig. 34) with a diameter of 2 ¾ to 6 ½ inches. They have

holes in the middle like phonograph records. They are held upright

against 7 ¾-inch-high obelisks by pegs. Once again I do not believe

the archaeologists when they say that these ceremonial discs were

divine symbols of power and strength, and the obelisks phallic

symbols. I was fascinated by the jade discs, many of which had

neatly milled sharp angles like those on toothed wheels round their

circumference. Is there some connection between these so-called

ceremonial discs and the stone plates from

Baian Kara Ula?

If we accept that the plates from the Sino-Tibetan border region

were models for the ceremonial discs,

the veil enshrouding the mystery would be lifted. After a visit to

the Baian Kara Ula region by the

astronauts who made the plates, presumably for transmitting

information, reverent priests imagined

that they would be doing work pleasing to God or even acquire some

of the qualities of the brilliantly

clever beings who had vanished simply by making discs like those

that the strangers had used. That

would square with the current archaeological explanation of the

discs, for by this roundabout route

they actually could have become religious trappings.

Dr. Vyacheslav Saizev, who published important data about the stone

plates,

found a rock painting (Fig. 35)

near Fergana, in Uzbekistan,

not far from the Chinese frontier. Not only does the figure wear an

astronaut’s helmet, not only can we identify breathing apparatus,

but in his hands, isolated by the spaceman’s suit, he holds a plate

of the kind found by the hundreds at Baian Kara Ula!

One day I picked

up the Dictionary of Chinese Mythology and read the legend of Yuan

Shih Tien Wang, which I reproduce here in abbreviated form:

“In a long past age the ancient sage Yuan Shih Tien Wang lived in

the mountain on the edge of the eternal ice. He told stories about

olden times in such picturesque language that those who heard him

believed that Yuan Shih himself had been present at all the

wonderful events. One of his listeners, Chin Hung, asked the sage

where he had lived before he had come to the mountain.

Without a

word, Yuan Shih raised both arms until they pointed to the stars.

Then Chin Hung wanted to know how he could find his way in the

infinite void of the heavens. Yuan Shih kept silent, but two gods in

shining armor appeared and Chin Hung, who was present, told his

people that one god had said: ‘Come, Yuan Shih, we must go. We shall

wander through the darkness of the universe and travel past distant

stars to our home.’”

Fig. 35.

Dr. Vyacheslav Saizev found this rock

painting near Fergana, in Uzbekistan.

An astronaut holds a disc,

similar to those found by the hundred at Baian Kara Ula. A

recording?

(for more info click

above image)

Taipeh, the capital of Formosa (or Taiwan) and Nationalist China,

has nearly two million inhabitants,

universities, high schools and exceptionally well-run museums. From

its main port of Keelung products such as sugar, tea, rice, bananas,

pineapples (which flourish in the tropical monsoon climate), wood,

camphor and fish are exported.

Since Taiwan, with a population of

13,000,000, became an independent country in 1949, its industry has

grown at a fantastic rate, so that today textiles, all kinds of

engines, agricultural machinery, electrical goods, etc., with “Made

in Taiwan” stamped on them, are loaded on to ships for customers all

over the world. The government encourages the mining of gold,

silver, copper and coal, which brings in foreign exchange. Once

again it is not clear whence and when the original Mongolian

inhabitants, the Paiwan, came to the island.

Today a quarter of a

million of them live in seven different tribes in the most

inaccessible part of the mountain range, where they were driven by

successive waves of Chinese invaders. Only a generation ago, Paiwan

warriors showed their bravery by head-hunting; today they hunt game

in their mountain fastness. The tribes have survived in a remarkably

pure state; they live according to the unchanging laws of nature.

Their way of reckoning time is as simple as their way of life. The

day begins at cockcrow; its passage is measured by the length of the

shadows.

The new year is recognized when the mountain plants start

to blossom, its high point when the fruit ripens, its end with the

first snow which cuts the tribes off from the world completely.

Fig. 36.

The chieftain lived here! The two floating figures to the

left of the four concentric circles

wear the classical aprons of

prehistoric astronauts to be found on many monoliths.

From very

early times, the Paiwans have practiced monogamy, so it is

unimportant whether a suitor buys or abducts his bride, or woos her

bashfully; the only thing that matters is that he keeps her for Me.

The Paiwan’s favorite stimulant is betel, which he manufactures in

his own homemade “laboratory” from the nutmeg-like fruits of the

betel palm, with the addition of burnt lime and a good pinch of

betel pepper. Betel tastes as bitter as gall, but is supposed to be

refreshing.

As betel turns spittle red and teeth blue-black, the

friendly grin of a Paiwan warrior is frightening rather than

reassuring. If I had not been reliably assured that they no longer

practice head-hunting, I would have beaten a hasty retreat, because

I need my head a little longer.

The Museum of the Province of Taipeh possesses a unique collection

of Paiwan wood carvings. Thenwood

sculptures are considered to be the last examples of a dying folk

art. They preserve primeval

motifs from sagas and legends that have been handed down for many,

many generations.

Fig. 37.

Toltec monoliths in the Museum fur Volkerkunde, Berlin.

The left-hand picture is entitled “Ode to the

Sun God.” It comes from Gods from Outer Space.

The right-hand one is

my own photograph from the American Museum in Madrid,

which has

plaster casts of the original.

The important thing is the “aprons,”

for the Paiwan tribe of Formosa scratch the same aprons on wood and

stone

when depicting their own gods. Were they part of astronauts’

uniforms?

The man who seeks for gods will find them.

Hanging in the museum was a piece of wood 28 inches wide by 10

inches high. (Fig. 36.) Once upon a time, when hung on a hut, it

meant: the chief lives here! To the left of the four striking

concentric circles float two figures, who are wearing the by now

classical “aprons” of prehistoric astronauts, of the land to be

found, for example, on the Toltec monoliths (Fig. 37) in the Museum

fur Volkerkunde in Berlin. Both figures are wearing a kind of

overall, and shoes. The being on the left wears a helmet and

extended ultra-short-wave antennae.

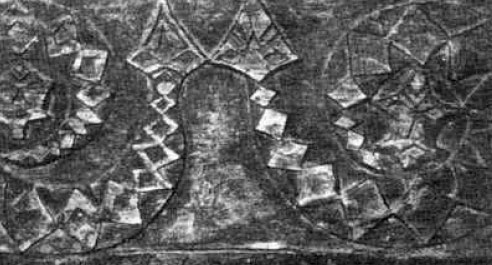

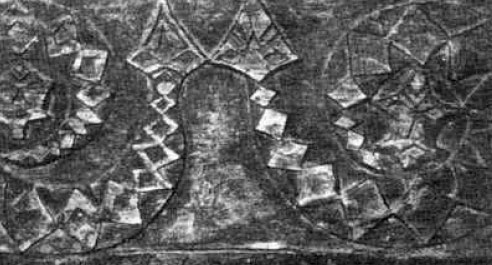

A wooden sculpture (Fig. 38) represents a being with large genital

organs, whose head is protected by

a close-fitting helmet. A small triangle is engraved on the helmet,

perhaps the emblem of his

astronautical formation. A snake twines round his helmet. Symbol of

loathsomeness in biblical times,

in the sagas of the Mayas the snake rose again into the air as a

“feathered creature,” and now it crops

up again here among forgotten tribes in the mountain ranges of

Formosa. All over the world we find

snakes, flying snakes, in traditional popular art!

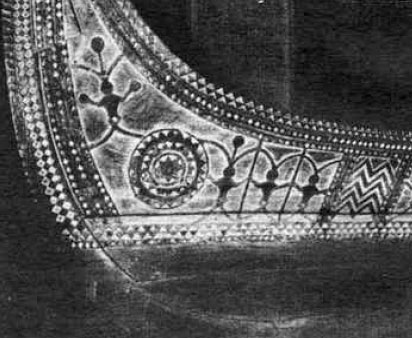

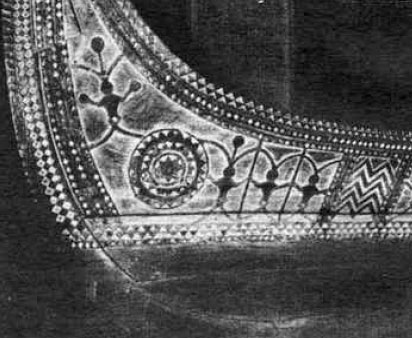

Why did the Paiwan paint their canoes (Fig. 39) with snakes, why are

the heads of the “divine figures” round like helmets, why are they

in (antenna) contact with each other and why do the contacts end in

a “sun” with a series of toothed wheels inside it? Why do snakes

(Fig. 40), twined round stars, gaze steadily heavenwards with their

triangular heads? Why does a Paiwan god hold a snake that passes

above him and his helmet? Why in particular is a female goddess

(Fig. 42) concealed in a mask, why does she wear clumsy goggles and

why is there a snake above and around her head? Obviously this

outfit was never chic, but it was suitable for a space flight and

the snake symbolized a limit to cosmic flight.

All this should be interpreted in terms of early religions, say the

archaeologists. They say that snakes were divine “symbols of

reverence.” If so, why did not the Paiwans use fish, sharks, waves

or turtles as models, when they painted their canoes with symbols of

religious provenance? Why did not the chief pin a shield that bore

the sign of his tribe (there were some beautiful ones) on the wall

of his house?

The carvings, which are often half-rotten, are extremely lovely.

They all have concentric circles and spirals, and they continually

emphasize the connection between man and snake, with the snake

always hissing heavenwards above the figure. Frequently the figures

are carved in a floating, as opposed to a standing position, as if

they were weightless. I do not think such reproductions were the

products of artistic imagination. The first ancestors of the Paiwan

must have seen that it was possible for beings to float in the air

and told their descendants so.

Fig. 38.

This figure has a ray gun in his hand, like those in the

pictures of the gods at Val Camonica, Italy,

and Monte Alban,

Mexico. And a snake is coiled round his helmet. A space symbol.

Fig.

39.

Why did the Paiwan paint their canoes with frescoes of the gods,

like the ancient Egyptians?

What do the figures’ linking up antennae mean?

Fig. 40

Snakes coiling round stars with their triangular heads

staring heavenwards On a Paiwan wooden tablet.

Fig 41

This wooden sculpture shows a god with a tight-fitting helmet

and once again a snake,

the ancient emblem of the space traveler.

Fig. 42.

Paiwan goddess in a space traveler’s mask.

She holds a

snake, symbol of the universe, in her hands.

The Paiwan are still primitive even today. In their masterly

carvings they represent both real things from their environment and

also the stereotypes which come from a kind of collective

unconscious going back to time immemorial Their contemporary

woodwork shows that the Paiwan carvers are quite up to date.

They

perpetuate men in Japanese uniforms, with their weapons. They have

seen these men. They are not straining their imaginations. They have

never done so; in all ages they represented what they had actually

seen in artistically perfect combination with traditional motifs. An

especially remarkable motif is a three-headed being flying in a

snake-a motif that recurs in a silk manuscript of the Chou culture

(1122-236 B.C.).

Mr. Y.C. Wang, Director of the Historical Museum, Taipeh, showed me

round his collection of representations of mythological beings, half

men, half animals, often with bird’s heads on winged bodies,

parallels to the Assyrian and Babylonian winged gods. Seals from the

Chou period are as numerous as the rings in a jeweler’s showcase. Up

to 1 centimeter in size they do not appear to have been simply

decorative ornaments. Under my magnifying glass, they looked

remarkably like integrated circuits.

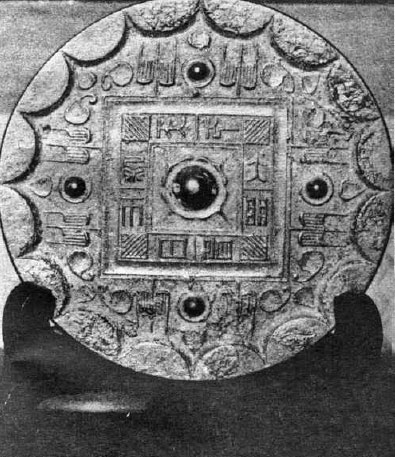

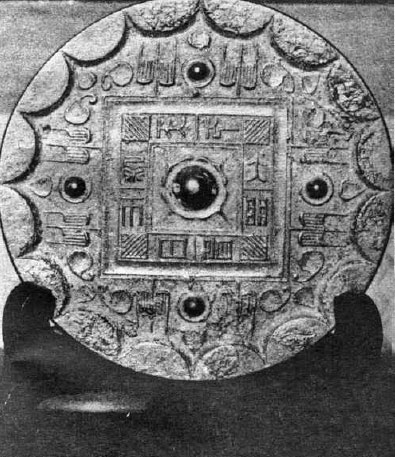

There were also some “bronze mirrors” from 2 ¾ inches to 5 inches in

diameter engraved with symbols and characters that have been

partially deciphered.

The translated text of an engraved inscription from the Chou dynasty

reads:

“Wherever suns shine, there is life.”

For amusement’s sake, I have reproduced the square in the center of

this bronze mirror (Fig. 43) in comparison with two integrated

circuits from the firm of Siemens.

The geologist Thuinli Lynn told me about a discovery that is unknown

to the western world.

Fig. 43.

“Wherever suns shine, there is life,”

reads the inscription oh a bronze mirror.

Engravings like those on

this mirror could easily be taken for modern integrated circuits!

During excavations in the “Valley of Stones” in July, 1961,

Chi Pen

Lao, Professor of Archaeology in the University of Peking, came

across an underground cave system. At a depth of 105 feet he found

entrances to a labyrinth in the spurs of the Honan mountains, on the

south shore of Lake Tung Ting, west of Yoyang. He located passages

that undoubtedly led under the lake.

The passage walls were smooth

and glazed. The walls of one hall, into which several passages led,

were covered with paintings. They represented animals, all fleeing

in one direction, driven by men who held “blowpipes” to their lips.

Above the fleeing animals, and this is the sensational part of the

account as far as I am concerned, flies a shield on which stand men

holding weapon-like implements which they are aiming at the animals.

The men on the “flying shield,” says Mr.

Chi Pen Lao, wear modern

jackets and long trousers. Mr. Lynn thinks that scholars have

probably succeeded in establishing the date when the tunnel was

built, but news from Red China only emerges sparingly and after long

delays. The report of the “flying shield” and the men aiming at the

animals from above at once reminded me of a museum piece which had

left an indelible impression on my memory. It was the skeleton of a

bison (Fig. 44), whose brow had been pierced by a neat shot, and I

had seen it in the Museum of Paleontology in Moscow.

The original home of the bison was Russian Asia. The age of my

fossil bison was dated to the Neolithic (8000 to 2700 B.C.), when

weapons were still made by flaking stones, and the most modern

weapon created in that period was the stone axe.

A blow with a stone axe would inevitably have shattered the bison’s

skull, but under no circumstances could it have left a bullet hole.

A firearm in the Neolithic? In fact, the idea seems so absurd that

the experts could dismiss it with a wave of the hand, if it were not

for the fact that the Neolithic marksman’s bison trophy is on show

in Moscow.

Fig. 44.

This skeleton of a bison from the Neolithic can be seen in

the Museum of Paleontology in Moscow.

The hole in the skull could

only have been made by a firearm.

Who on earth possessed firearms in

8000 B.C.?

Fig. 45.

On the night before my departure from Taipeh

President Ku

Cheng-Kang gave a dinner for me attended by scholars, politicians

and museum directors.

They all helped my inquiries.

On the eleventh

and last day of my stay in Taipeh, President Ku Cheng Kang, Member

of the National Assembly, gave a dinner for me. I was surrounded by

distinguished politicians and scholars: B. Hsieh, Professor at Fuyen

University, Shun Yao, still UNESCO Secretary-General representing

the Republic in January, 1972, Hsu Chih Hsin and Shuang Jeff Yao of

the Public Relations Department, Senyung Chow of the Government and

of course my museum friends, Chiang, Lynn, Wang and Wu.

These

gentlemen’s names are supposed to be as common as Smith, Jones and

Brown. I tried hard to identify all the happy smiling faces, but I

could not manage to put the right name to them. While I was flying

to the Pacific island of Guam by TWA, I drew up a balance of my

visit. I had not been able to see the report on Baian Kara Ula, but

I had been able to eliminate a white spot on my map of the abodes of

the gods on Chinese territory.

PS.: My film Chariots of the Gods? has been bought by Comrade Mao’s

State Film Lending Library. Perhaps he will help me to make a study

trip to Peking. With a post-card in my hand, I’ll easily find my way

to the Academy with the historical archives.

Besides I have been wanting to visit the Gobi Desert for a long

time.

Back to Contents

|