|

by Rob Waugh

3 July 2012

from

DailyMail Website

Spanish version

Italian version

Divers have found traces of

ancient land swallowed by waves 8500 years ago

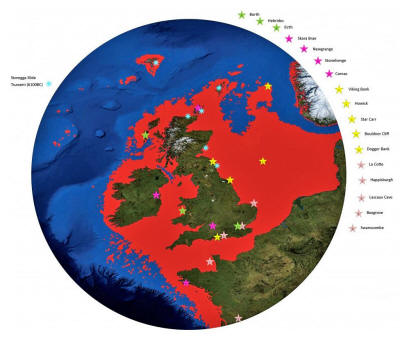

Doggerland once stretched from Scotland to Denmark

Rivers seen underwater by seismic scans

Britain was not an island - and area under North Sea

was roamed by

mammoths and other giant animals

Described as the 'real heartland' of Europe

Had population of tens of thousands - but devastated by sea level

rises

'Britain's Atlantis' - a hidden underwater world swallowed by the

North Sea - has been discovered by divers working with science teams

from the University of St Andrews.

Doggerland, a huge area of dry land that stretched from Scotland to

Denmark was slowly submerged by water between 18,000 BC and 5,500

BC.

Divers from oil companies have found remains of a 'drowned world'

with a population of tens of thousands - which might once have been

the 'real heartland' of Europe.

A team of climatologists, archaeologists and geophysicists has now

mapped the area using new data from oil companies - and revealed the

full extent of a 'lost land' once roamed by mammoths.

Divers from St Andrews University, find remains of Doggerland,

the underwater

country dubbed 'Britain's Atlantis'

Dr Richard Bates of the earth sciences department at St Andrews

University,

searching for

Doggerland, the underwater country dubbed 'Britain's Atlantis'

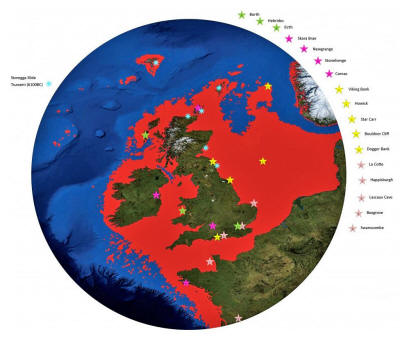

How the North Sea

grew and the land-mass shrunk

A Greater Britain: How the North Sea grew and the land-mass shrunk

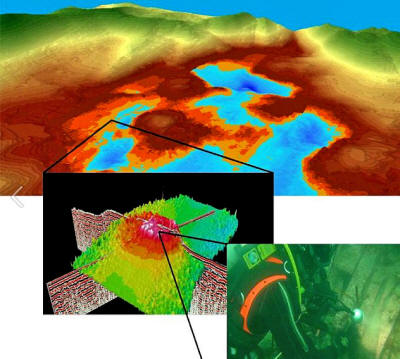

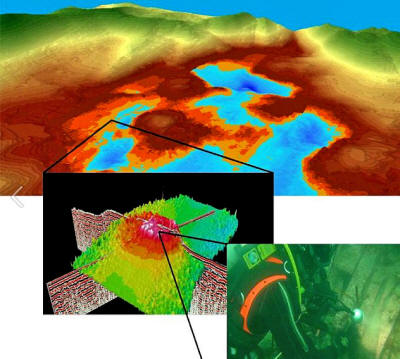

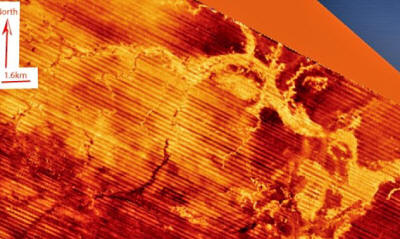

Scans show a mound discovered under the water near Orkney, which has

been explored by divers

Drowned world:

Scans show a mound

discovered under the water near Orkney,

which has been

explored by divers

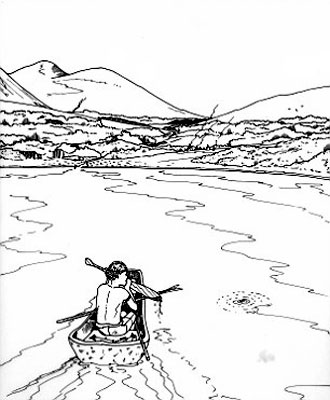

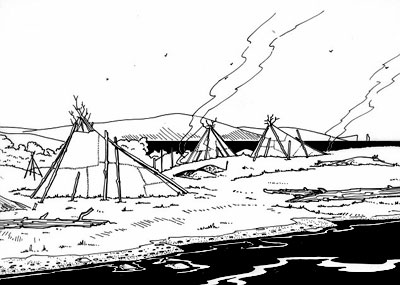

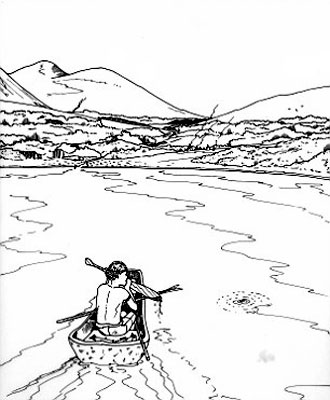

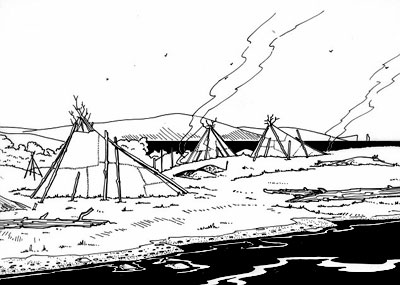

St Andrews University's artists' impression of life in Doggerland

The research suggests that the

populations of these drowned lands could have been tens of

thousands, living in an area that stretched from Northern Scotland

across to Denmark and down the English Channel as far as the Channel

Islands.

The area was once the ‘real heartland’ of Europe and was hit by ‘a

devastating tsunami', the researchers claim.

The wave was part of a larger process that submerged the low-lying

area over the course of thousands of years.

'The name was coined for Dogger

Bank, but it applies to any of several periods when the North

Sea was land,' says Richard Bates of the University of St

Andrews.

'Around 20,000 years ago, there was a 'maximum' -

although part of this area would have been covered with ice.

When the ice melted, more land was revealed - but the sea level

also rose.

'Through a lot of new data from oil and gas companies, we’re

able to give form to the landscape - and make sense of the

mammoths found out there, and the reindeer. We’re able to

understand the types of people who were there.

'People seem to think rising sea levels are a new thing - but

it’s a cycle of Earth history that has happened many many

times.'

Organized by Dr Richard Bates of

the Department of Earth Sciences at St Andrews, the Drowned

Landscapes exhibit reveals the human story behind Doggerland, a now

submerged area of the North Sea that was once larger than many

modern European countries.

Dr Bates, a geophysicist, said:

‘Doggerland was the real heartland

of Europe until sea levels rose to give us the UK coastline of

today.

World beneath the

waves:

Scientists examine a sediment core recovered from a mound

near Orkney

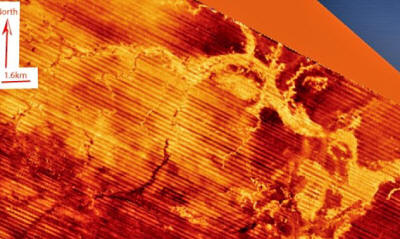

Seismic scans reveal a submerged river at Dogger Bank

Doggerland

A visualization of how life in the now-submerged areas

of Dogger

Bank might have looked

The research suggests that the populations of these drowned

lands

could have been

tens of thousands, living in an area that stretched from

Northern Scotland

across to Denmark

and down the English Channel as far as the Channel Islands

Life in 'Doggerland' - the ancient kingdom once stretched

from Scotland to

Denmark and has been described as the 'real heart of Europe'

‘We have speculated for years on the

lost land's existence from bones dredged by fishermen all over

the North Sea, but it's only since working with oil companies in

the last few years that we have been able to re-create what this

lost land looked like.

‘When the data was first being processed, I thought it unlikely

to give us any useful information, however as more area was

covered it revealed a vast and complex landscape.

‘We have now been able to model its flora and fauna, build up a

picture of the ancient people that lived there and begin to

understand some of the dramatic events that subsequently changed

the land, including the sea rising and a devastating tsunami.’

The research project is a collaboration

between St Andrews and the Universities of Aberdeen, Birmingham,

Dundee and Wales Trinity St David.

Rediscovering the land through pioneering scientific research, the

research reveals a story of a dramatic past that featured massive

climate change. The public exhibit brings back to life the

Mesolithic populations of Doggerland through artifacts discovered

deep within the sea bed.

The research, a result of a painstaking 15 years of fieldwork around

the murky waters of the UK, is one of the highlights of the London

event.

The interactive display examines the lost landscape of Doggerland

and includes artifacts from various times represented by the exhibit

- from pieces of flint used by humans as tools to the animals that

also inhabited these lands.

Using a combination of geophysical modeling of data obtained from

oil and gas companies and direct evidence from material recovered

from the seafloor, the research team was able to build up a

reconstruction of the lost land.

The excavation of

Trench 2,

unveiling more finds

about this lost land-mass

Fossilized bones from a mammoth also show

how this landscape

was once one of hills and valleys, rather than sea

The findings suggest a picture of a land

with hills and valleys, large swamps and lakes with major rivers

dissecting a convoluted coastline.

As the sea rose the hills would have become an isolated archipelago

of low islands. By examining the fossil record - such as pollen

grains, microfauna and macrofauna - the researchers can tell what

kind of vegetation grew in Doggerland and what animals roamed there.

Using this information, they were able to build up a model of the

'carrying capacity' of the land and work out roughly how many humans

could have lived there.

The research team is currently investigating more evidence of human

behavior, including possible human burial sites, intriguing standing

stones and a mass mammoth grave.

Dr Bates added:

‘We haven't found an 'x marks the

spot' or 'Joe created this', but we have found many artifacts

and submerged features that are very difficult to explain by

natural causes, such as mounds surrounded by ditches and

fossilized tree stumps on the seafloor.

‘There is actually very little evidence left because much of it

has eroded underwater; it's like trying to find just part of a

needle within a haystack. What we have found though is a

remarkable amount of evidence and we are now able to pinpoint

the best places to find preserved signs of life.’

For further information on the exhibit,

visit:

http://sse.royalsociety.org/2012/exhibits/drowned-landscapes/

|