|

|

|

from NewsWire Website

Individual organs may possess innate, individual immune systems separate from the body's larger immune system, suggests a study

When an infection strikes, the cells, produced in bone marrow, race through the blood to fight off the pathogen. But new research is emerging that individual organs can also play a role in immune system defense, essentially being their own hero.

In a study examining a rare and deadly

brain infection, scientists at The Rockefeller University have found

that the brain cells of healthy people likely produce their own

immune system molecules,

demonstrating an “intrinsic immunity”

that is crucial for stopping an infection.

The scientists already knew from previous work (read 'Heterozygous TBK1 Mutations Impair TLR3 Immunity and Underlie Herpes Simplex Encephalitis of Childhood') that children with this encephalitis have a genetic defect that impairs the function of an immune system receptor - toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) - in the brain.

For this study they wanted to see how

the defect in TLR3 was hampering the brain’s ability to fight the

herpes infection.

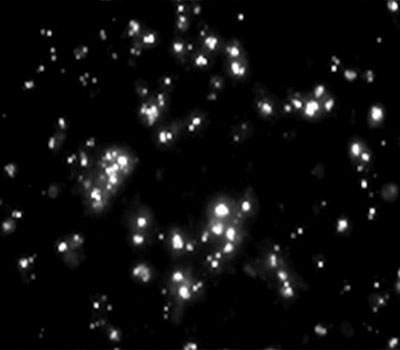

Herpes simplex virus-infected neurons (above) are from patients with a genetic defect that impairs their brain’s ability to make interferon, an important immune system protein, and leaves their brain cells unable to fight off the infection.

Healthy people, in

turn, have an intrinsic immune response to the virus.

When TLR3 detects a pathogen it triggers an immune response causing the release of proteins called interferons to sound the alarm and “interfere” with the pathogen’s replication.

It’s most commonly associated with white blood cells, found throughout the body, but here the researchers were examining the receptor’s presence on neurons and other brain cells.

The lab, headed by Jean-Laurent Casanova, collaborated with scientists at Harvard Medical School and Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Institute to create induced pluripotent stem cells.

Made from the patients’ own tissue, the stem cells were developed into central nervous system cells that carried the patients’ genetic defects. Zhang exposed the cells to HSV-1 and to synthetic double-stranded RNA, which mimics a byproduct of the virus that spurs the toll-like receptors into action.

By measuring levels of interferon, Zhang

showed that the patients’ TLR3 response was indeed faulty; their

cells weren’t making these important immune system proteins, leaving

them unable to fight off the infection.

When its function was impaired, patients couldn’t get better.

The researchers are putting together a pilot study to test an interferon-based treatment in patients with the encephalitis, believing it will help speed recovery and increase the survival rate when used alongside antiviral drugs.

They’ll also explore whether the brain displays an intrinsic immunity to other types of viral infection.

Journal Reference

|