|

2009

from

ViewZone Website

COPENHAGEN (AFP)

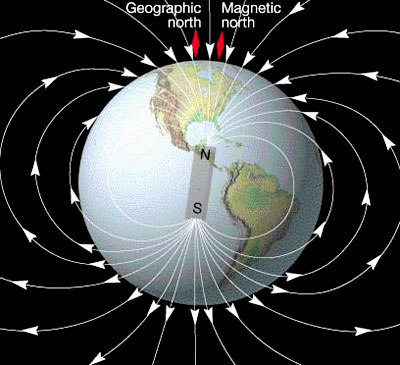

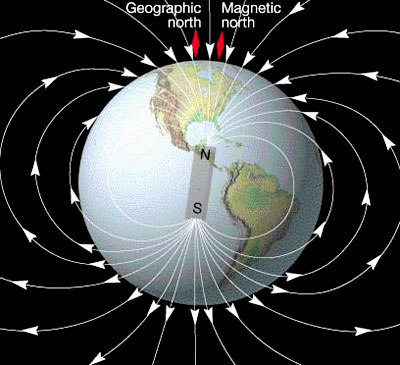

The earth's climate has been

significantly affected by the planet's magnetic field, according to

a Danish study published Monday that could challenge the notion that

human emissions are responsible for global warming.

"Our results show a strong

correlation between the strength of the earth's magnetic field

and the amount of precipitation in the tropics," one of the two

Danish geophysicists behind the study, Mads Faurschou Knudsen of

the geology department at Aarhus University in western Denmark,

told the Videnskab journal.

He and his colleague Peter Riisager,

of the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS),

compared a reconstruction of the prehistoric magnetic field 5,000

years ago based on data drawn from stalagmites and stalactites found

in China and Oman.

The results of the study, which has also been published in US

scientific journal Geology, lend support to a controversial theory

published a decade ago by Danish astrophysicist Henrik Svensmark,

who claimed the climate was highly influenced by galactic cosmic

ray (GCR)

particles penetrating the earth's atmosphere.

Svensmark's theory, which pitted him against today's mainstream

theorists who claim carbon dioxide (CO2) is responsible

for global warming, involved a link between the earth's magnetic

field and climate, since that field helps regulate the number of GCR

particles that reach the earth's atmosphere.

"The only way we can explain the

(geomagnetic-climate) connection is through the exact same

physical mechanisms that were present in Henrik Svensmark's

theory," Knudsen said.

"If changes in the magnetic field, which occur independently of

the earth's climate, can be linked to changes in precipitation,

then it can only be explained through the magnetic field's

blocking of the cosmetic rays," he said.

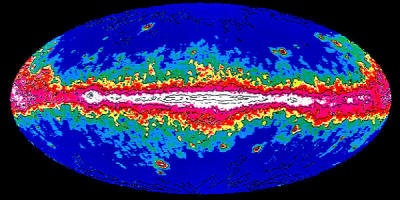

Galactic

Cosmic Rays

Galactic cosmic rays (GCRs)

come from outside the solar system but generally from within our

Milky Way galaxy.

GCRs are atomic nuclei from which all of

the surrounding electrons have been stripped away during their

high-speed passage through the galaxy.

They have probably been accelerated

within the last few million years, and have traveled many times

across the galaxy, trapped by the galactic magnetic field.

GCRs have

been accelerated to nearly the speed of light, probably by supernova

remnants.

As they travel through the very thin gas

of interstellar space, some of the GCRs interact and emit gamma

rays, which is how we know that they pass through the Milky Way and

other galaxies.

The elemental makeup of GCRs has been studied in detail , and is

very similar to the composition of the Earth and solar system. But

studies of the composition of the isotopes in GCRs may indicate the

that the seed population for GCRs is neither the interstellar gas

nor the shards of giant stars that went supernova.

This is an area of current study.

Included in the cosmic rays are a number of radioactive nuclei whose

numbers decrease over time. As in the carbon-14 dating technique,

measurements of these nuclei can be used to determine how long it

has been since cosmic ray material was synthesized in the galactic

magnetic field before leaking out into the vast void between the

galaxies.

These nuclei are called "cosmic ray

clocks".

The two scientists acknowledged that CO2

plays an

important role in the changing climate,

"but the climate is an incredibly

complex system, and it is unlikely we have a full overview over

which factors play a part and how important each is in a given

circumstance," Riisager told Videnskab.

Svensmark's

Theory Explained

Man-made climate change may be happening at a far slower rate than

has been claimed, according to controversial new research.

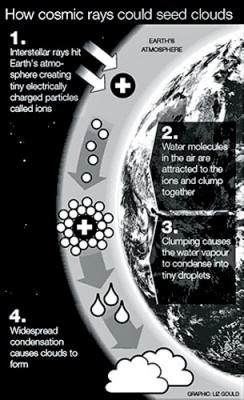

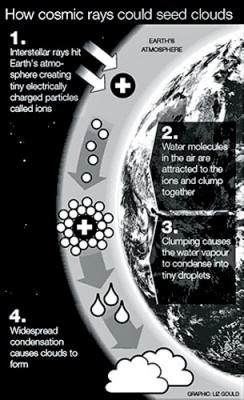

Scientists say that cosmic rays from

outer space play a far greater role in changing the Earth's climate

than global warming 'experts' previously thought.

In a book, to be published this week, they claim that fluctuations

in the number of cosmic rays hitting the atmosphere directly alter

the amount of cloud covering the planet.

High levels of cloud cover blankets the Earth and reflects radiated

heat from the Sun back out into space, causing the planet to cool.

Henrik Svensmark, a weather scientist at the Danish National

Space Centre who led the team behind the research, believes that

the planet is experiencing a natural period of low cloud cover due

to fewer cosmic rays entering the atmosphere.

This, he says, is responsible for much of

the global 'warming' we are

experiencing.

He claims carbon dioxide emissions due to human activity are having

a smaller impact on climate change than scientists think. If he is

correct, it could mean that mankind has more time to reduce our

effect on the climate.

The controversial theory comes one week after 2,500 scientists who

make up the United Nations International Panel on Climate Change

published their fourth report stating that human carbon dioxide

emissions would cause temperature rises of up to 4.5°C by the end of

the century.

Mr Svensmark claims that the calculations used to make this

prediction largely overlooked the effect of cosmic rays on cloud

cover and the temperature rise due to human activity may be much

smaller.

He said:

"It was long thought that clouds

were caused by climate change, but now we see that climate

change is driven by clouds.

"This has not been taken into account in the models used to work

out the effect carbon dioxide has had.

"We may see CO2 is responsible for much less warming

than we thought and if this is the case the predictions of

warming due to human activity will need to be adjusted."

Mr Svensmark last week published (Influence

of Cosmic Rays on Earth's Climate)

the first experimental evidence from five years' research on the

influence that cosmic rays have on cloud production in the

Proceedings of the Royal Society Journal A: Mathematical, Physical

and Engineering Sciences.

This week he will also publish a fuller

account of his work in a book entitled

The Chilling Stars - A New Theory of Climate

Change.

A team of more than 60 scientists from around the world are

preparing to conduct a large-scale experiment using a particle

accelerator in Geneva, Switzerland, to replicate the effect of

cosmic rays hitting the atmosphere.

They hope this will prove whether this deep space radiation is

responsible for changing cloud cover. If so, it could force climate

scientists to re-evaluate their ideas about how global warming

occurs.

Mr Svensmark's results show that the rays produce electrically

charged particles when they hit the atmosphere.

He said:

"These

particles attract water molecules from the air and cause them to

clump together until they condense into clouds."

Mr Svensmark claims that the number of cosmic rays hitting the Earth

changes with the magnetic activity around the Sun.

During high

periods of activity, fewer cosmic rays hit the Earth and so there

are less clouds formed, resulting in warming.

Low activity causes more clouds and cools the Earth.

According to Svensmark:

"Evidence from ice cores show this

happening long into the past. We have the highest solar activity

we have had in at least 1,000 years.

"Humans are having an effect on climate change, but by not

including the cosmic ray effect in models it means the results

are inaccurate. The size of man's impact may be much smaller and

so the man-made change is happening slower than predicted."

Some climate change experts have

dismissed the claims as "tenuous".

Giles Harrison, a cloud specialist at Reading University said

that he had carried out research on cosmic rays and their effect on

clouds, but believed the impact on climate is much smaller than Mr

Svensmark claims.

Mr Harrison said:

"I have been looking at cloud data

going back 50 years over the UK and found there was a small

relationship with cosmic rays. It looks like it creates some

additional variability in a natural climate system but this is

small."

But there is a growing number of

scientists who believe that the effect may be genuine.

Among them is Prof Bob Bingham, a clouds expert from the Central

Laboratory of the Research Councils in Rutherford.

He said:

"It is a relatively new idea, but

there is some evidence there for this effect on clouds."

|