|

by Jonathan Leake

October 18, 2009

from

TimesOnLine Website

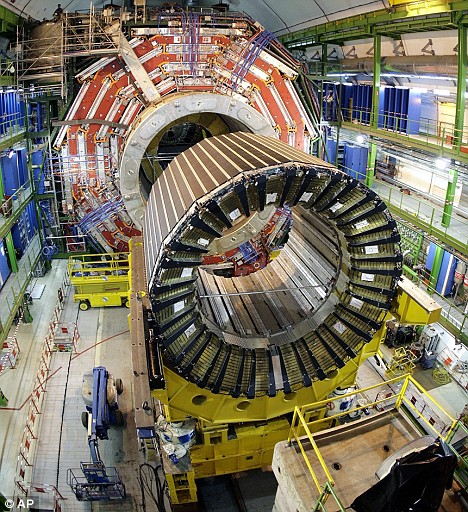

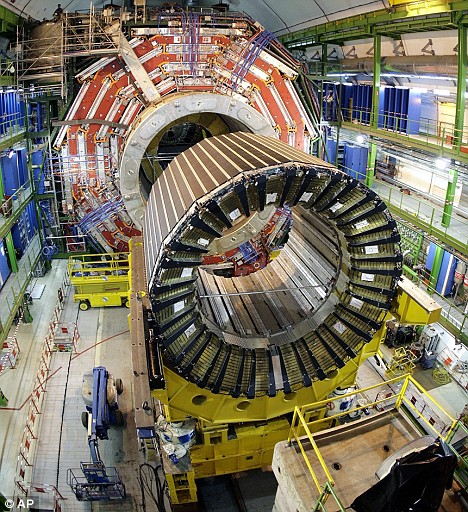

Hadron Collider

Explosions, scientists arrested for

alleged terrorism, mysterious breakdowns - recently Cern’s Large

Hadron Collider (LHC) has begun to look like the world’s most

ill-fated experiment.

Is it really nothing more than bad luck or is there something

weirder at work? Such speculation generally belongs to the lunatic

fringe, but serious scientists have begun to suggest that the

frequency of Cern’s accidents and problems is far more than a

coincidence.

The LHC, they suggest, may be sabotaging itself from the future -

twisting time to generate a series of scientific setbacks that will

prevent the machine fulfilling its destiny.

At first sight, this theory fits comfortably into the crackpot

tradition linking the start-up of the LHC with terrible disasters.

The best known is that the £3 billion particle accelerator might

trigger a

black hole capable of swallowing the Earth when it gets

going. Scientists enjoy laughing at this one.

This time, however, their ridicule has been rather muted - because

the time travel idea has come from two distinguished physicists who

have backed it with rigorous mathematics.

What Holger Bech Nielsen, of the Niels Bohr Institute

in Copenhagen, and Masao Ninomiya of the Yukawa Institute

for Theoretical Physics in Kyoto, are suggesting is that the

Higgs boson, the particle that

physicists hope to produce with the collider, might be “abhorrent to

nature”.

What does that mean?

According to Nielsen, it means that the

creation of the boson at some point in the future would then ripple

backwards through time to put a stop to whatever it was that had

created it in the first place.

This, says Nielsen, could explain why the LHC has been hit by

mishaps ranging from an explosion during construction to a second

big bang that followed its start-up. Whether the recent arrest of a

leading physicist for alleged links with Al-Qaeda also counts is

uncertain.

Nielsen’s idea has been likened to that of a man traveling back

through time and killing his own grandfather.

“Our theory suggests that any

machine trying to make the Higgs shall have bad luck,” he said.

“It is based on mathematics, but you could explain it by saying

that God rather hates Higgs particles and attempts to avoid

them.”

His warnings come at a sensitive time

for Cern, which is about to make its second attempt to fire up the

LHC.

The idea is to accelerate protons to

almost the speed of light around the machine’s 17-mile underground

circular racetrack and then smash them together. In theory the

machine will create tiny replicas of the primordial “big bang”

fireball thought to have marked the creation of the universe. But if

Nielsen and Ninomiya are right, this latest build-up will inevitably

get nowhere, as will those that come after - until eventually Cern

abandons the idea altogether.

This is, of course, far from being the first science scare linked to

the LHC. Over the years it has been the target of protests, wild

speculation and court injunctions.

Fiction writers have naturally seized on the subject. In Angels

and Demons, Dan Brown sets out a diabolical plot in which

the Vatican City is threatened with annihilation from a bomb based

on antimatter stolen from Cern.

Blasphemy, a novel from

Douglas Preston, the bestselling science-fiction author, draws

on similar themes, with a story about a mad physicist who wants to

use a particle accelerator to communicate with God. The

physicist may be American and the machine located in America, rather

than Switzerland, but the links are clear.

Even Five, the TV channel, has got in on the act by screening

FlashForward, an American series based on Robert Sawyer’s novel of

the same name in which the start-up of the LHC causes the Earth’s

population to black out for two minutes when they experience visions

of their personal futures 21 years hence. This gives them a chance

to change that future.

Scientists normally hate to see their ideas perverted and twisted by

the ignorant, but in recent years many physicists have learnt to

welcome the way the LHC has become a part of popular culture. Cern

even encourages film-makers to use the machine as a backdrop for

their productions, often without charging them.

Nielsen presents them with a dilemma. Should they treat his

suggestions as fact or fiction? Most would like to dismiss him, but

his status means they have to offer some kind of science-based

rebuttal.

James Gillies, a trained physicist who heads Cern’s

communications department, said Nielsen’s idea was an interesting

theory,

“but we know it doesn’t happen in

reality”.

He explained that if Nielsen’s

predictions were correct then whatever was stopping the LHC would

also be stopping high-energy rays hitting the atmosphere. Since

scientists can directly detect many such rays,

“Nielsen must be wrong”, said

Gillies.

He and others also believe that although

such ideas have an element of fun, they risk distracting attention

from the far more amazing ideas that the LHC will tackle once it

gets going.

The Higgs boson, for example, is thought to give all other matter

its mass, without which gravity could not work. If the LHC found the

Higgs, it would open the door to solving all kinds of other

mysteries about the origins and nature of matter. Another line of

research aims to detect dark matter, which is thought to comprise

about a quarter of the universe’s mass, but made out of a kind of

particle that has so far proven impossible to detect.

However, perhaps the weirdest of all Cern’s aspirations for the LHC

is to investigate

extra dimensions of space. This idea, known as

string theory, suggests there are many more dimensions to space than

the four we can perceive.

At present these other dimensions are hidden, but smashing protons

together in the LHC could produce gravitational anomalies,

effectively tiny black holes, that would reveal their existence.

Some physicists suggest that when billions of pounds have been spent

on the kit to probe such ideas, there is little need to invent new

ones about time travel and self-sabotage.

History shows, however, it is unwise to dismiss too quickly ideas

that are initially seen as science fiction.

Peter Smith, a science

historian and author of

Doomsday Men, which looks at the links

between science and popular culture, points out that what started as

science fiction has often become the inspiration for big

discoveries.

“Even the original idea of the

‘atomic bomb’ actually came not from scientists but from H G

Wells in his 1914 novel The World Set Free,” he said.

“A scientist named Leo Szilard read it in 1932 and it gave him

the inspiration to work out how to start the nuclear chain

reaction needed to build a bomb. So the atom bomb has some of

its origins in literature, as well as research.”

Some of Cern’s leading researchers also

take Nielsen at least a little seriously.

Brian Cox, professor of

particle physics at Manchester University, said:

“His ideas are

theoretically valid. What he is doing is playing around at

the edge of our knowledge, which is a good thing. He is pointing out that we don’t

yet have a quantum theory of gravity, so we haven’t yet proved

rigorously that sending information into the past isn’t

possible.

However, if

time travelers do break into the LHC control room

and pull the plug out of the wall, then I’ll refer you to my

article supporting Nielsen’s theory that I wrote in 2025.”

This weekend, as the interest in his

theories continued to grow, Nielsen was sounding more cautious.

“We are seriously proposing the

idea, but it is an ambitious theory, that’s all,” he said. “We

already know it is not very likely to be true. If the LHC

actually succeeds in discovering the Higgs boson, I guess we

will have to think again.”

|