|

by David Shiga

23 November 2009

from

NewScientist Website

The Large Hadron Collider bashed

protons together for the first time on Monday (23 November 2009),

inaugurating a new era in the quest to uncover nature's deepest

secrets.

Housed in a 27-kilometre circular underground tunnel near Geneva,

Switzerland, the LHC is the world's most powerful particle

accelerator, designed to collide protons together at unprecedented

energies.

It was on the verge of its first proton collisions in September 2008

when a faulty electrical connection triggered an explosion of helium

used to cool the machine.

This caused a 14-month delay while CERN

repaired the damage and installed safety features to prevent a

repeat of the accident.

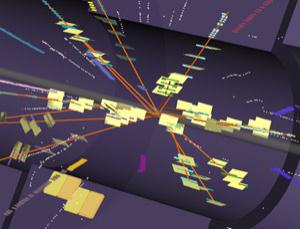

The LHC's first

collisions occurred on 23 November in the ATLAS detector, as

reconstructed here

(Image: CERN)

But physicists started whipping protons around the machine again on

Friday.

Now, at long last,

CERN is heralding the first collisions inside the

machine. Two beams of protons traveling at nearly the speed of light

crashed together on Monday at 13:22 GMT inside the ATLAS detector,

one of the giant measuring devices the LHC will use to probe

shrapnel from the collisions, according to CERN's announcement.

Further collisions occurred inside the

LHC's CMS and LHCb detectors.

"This is great news, the start of a

fantastic era of physics – and hopefully discoveries – after 20

years' work by the international community to build a machine

and detectors of unprecedented complexity and performance," said

Fabiola Gianotti, a spokesperson for the ATLAS detector project.

The protons collided with 900 billion

electron volts of energy (900 GeV),

with 450 GeV supplied by each beam. The LHC is designed to allow

collisions at much higher energies – all the way up to 14,000 GeV

(14 TeV), or 7 TeV per beam.

World record

Before a brief shutdown of the LHC for Christmas, CERN hopes to

boost the energy to 1.2 TeV per beam – exceeding the world's current

top collision energies of 1 TeV per beam at the

Tevatron accelerator in Batavia,

Illinois.

In early 2010, physicists will attempt to ramp up the energy to 3.5

TeV per beam, collect data for a few months at that energy, then

push towards 5 TeV per beam in the second half of the year.

The LHC has the potential to make new discoveries even before it

ramps up to its highest energies, Gianotti said in a CERN

press conference on Monday.

"[At] an energy of 3.5 TeV per beam,

we do have a discovery potential which goes beyond the present

detectors, so we may discover something new already next year,"

she said.

Supersymmetric

dark matter

Dark matter particles predicted by

supersymmetry – a theory that proposes hidden connections between

matter particles and particles that transmit forces – might be an

early discovery of the LHC, depending on how much the particles

weigh, said CERN director-general Rolf Heuer.

"If nature has really realized dark

matter in the form of supersymmetric low-mass particles, then

this will be the first thing they can discover," he said.

If the supersymmetric particles

are heavier or do not exist, then the LHC's first discovery might be

a sighting of the

Higgs boson, which is thought to

endow other particles with mass and would complete the so-called

standard model of physics.

Physicists are already designing successors to the LHC that could

reach even higher energies, such as the Super Large Hadron

Collider.

|