|

by Marco Torres

October 19, 2015

from

PreventDisease Website

-

What if our food has been

getting less and less nutritious?

-

What if modern intensive farming

methods - many of which solved malnutrition problems when

they were first introduced - have affected the mineral and

vitamin content of what we eat?

-

Could having a constant supply

of varied produce and introducing

genetically modified foods

be compromising nature's goodness?

Whether it be vegan, low carb, paleo, or any other diet, the quest

for the healthiest method of eating shows no sign of abating, yet

all have considerable controversy.

We know more than ever about what food

does to the body and the importance of

antioxidants,

healthy fats

and a low

glycaemic index.

Things have changed so much since the wisdom of our ancestors was

lost or ignored.

-

Wild dandelions, once a springtime treat for Native

Americans, have seven times more phytonutrients than spinach, which

we consider a "superfood."

-

A purple potato native to Peru has 28

times more cancer-fighting anthocyanins than common russet potatoes.

-

One species of apple has a staggering 100 times more phytonutrients

than the Golden Delicious displayed in our supermarkets.

Were the people who foraged for these wild foods healthier than we

are today?

They did not live nearly as long as we

do, but growing evidence suggests that they were much less likely to

die from degenerative diseases, even the minority who lived 70 years

and more. The primary cause of death for most adults, according to

anthropologists, was injury and infections.

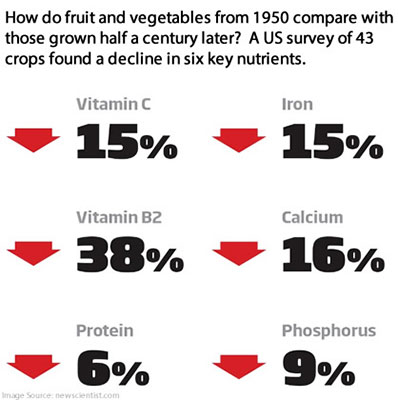

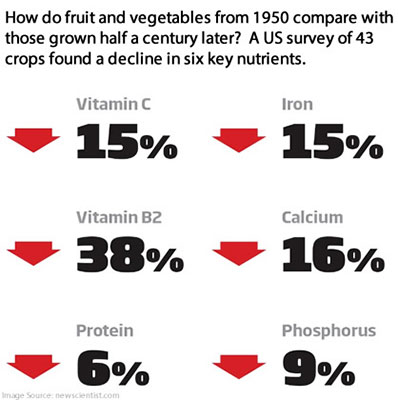

Some of the most eye-catching work

in this area has come from Donald Davis, a now-retired

biochemist at the University of Texas.

In 2011,

he compared the nutrients in US crops from 1950 and 2009, and

found notable declines in five nutrients in various fruits,

including tomatoes, eggplants and squash. For example, there was a

43 per cent drop in iron and a 12 per cent decline in calcium.

This was in line with his 1999 study -

mainly of vegetables -

which found a 15 per cent drop in vitamin C and a 38 per cent fall

in vitamin B2.

Fruit and vegetables grown have shown

similar depletions.

A 1997 comparison of

data from the 1930s and 1980s found

that calcium in fresh vegetables appeared to drop by 19 per cent,

and iron by 22 per cent. A

reanalysis of the data in 2005 concluded that 1980s

vegetables had less copper,

magnesium and sodium, and fruit less copper, iron and potassium.

Genetically modified

organisms (GMOs) in food have also alarmed researchers on distinct

differences between organic and GMO produce. Higher antioxidant

levels, lower pesticide loads, better farming practices all lead to

a more nutritious end product when choosing organic over GMO foods.

For

example, tomatoes grown by organic methods

contain more phenolic compounds than those grown using

commercial standards.

That

study - published in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry

- analyzed the phenolic profiles of Daniela tomatoes grown either

using 'conventional' or organic methods, finding that those grown

under organic conditions contained significantly higher levels of

phenolic compounds than those grown conventionally.

Other findings published in the Journal of

Agricultural and Food Chemistry showed that

organically produced apples have a

15 percent higher antioxidant capacity than conventionally produced apples.

Davis and others blame agricultural

practices that emphasize quantity over quality.

High-yielding crops produce more food,

more rapidly, but they can't make or absorb nutrients at the same

pace, so the nutrition is diluted.

"It's like taking a glass of orange

juice and adding an equal amount of water to it. If you do that,

the concentration of nutrients that was in the original juice is

dropped by half," says Davis.

But the idea that modern agriculture

produces crops that are less nourishing remains controversial, and

"then and now" nutritional comparisons have been much criticized.

The differences found may be down to

older, less accurate methods of assessing nutrition, and nutrient

levels can vary widely according to the variety of plant, the year

of harvest and the time of harvest.

Contrary to frequent claims that there is no evidence of dangers to

health from GM foods and crops, peer-reviewed studies have found

harmful effects on the health of laboratory and livestock animals

fed GMOs. Effects include toxic and allergenic effects and altered

nutritional value.

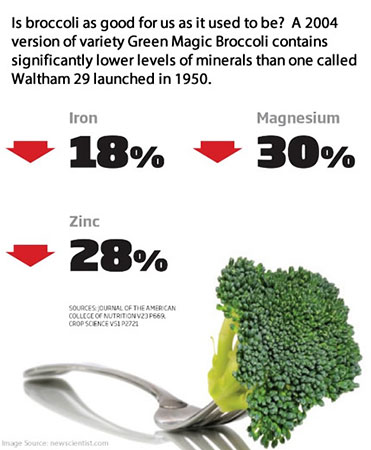

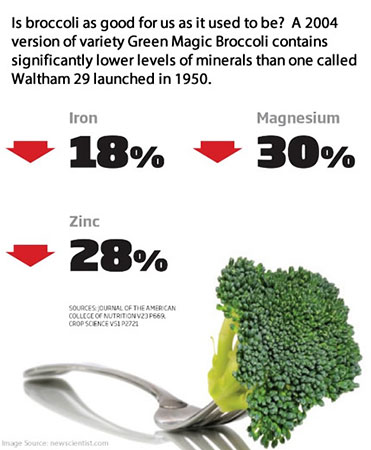

Other studies have sought to get round this by comparing old and new

varieties of a crop grown side by side. In 2011, researchers at the

US Department of Agriculture measured the concentrations of 11

minerals in 14 commercial varieties, or cultivars, of broccoli

launched between 1950 and 2004.

They found no clear relationship between

mineral levels and the year that a particular cultivar was released,

but there was evidence of a dilution effect:

bigger broccoli heads favored today

had

lower levels of some

minerals relative to a 1950 variety called Waltham 29.

But, as the study also noted, Waltham 29

is less tough than modern cultivars and so would be unlikely to

succeed if grown in the same way.

And there lies the rub.

Even if the arrival of intensive

agriculture has meant that our vegetables contain slightly less

nutrients than those our grandparents ate, it has also led to a huge

increase in food supply, which has undoubtedly had a positive effect

on our diet and health.

"Some evidence suggests that some

nutrients have fallen, particularly trace elements such as

copper in vegetables," says Paul Finglas, who compiles

nutritional data on UK food at the Institute of Food Research in

Norwich.

"Foods are now bred for yield, and

not necessarily nutritional composition. But I don't think that

is a problem, because we eat a wider range of foods today than

we did 10 years ago, let alone 40 years ago".

Other crops are also getting subtly less

nutritious.

The introduction of semi-dwarf,

higher-yielding varieties of wheat in the green revolution of the

1960s means that modern crops contain lower levels of iron and zinc

than old-fashioned varieties.

Each fruit and vegetable in our stores has a unique history of

nutrient loss, and there are two common themes.

Throughout the ages, our farming

ancestors have chosen the least bitter plants to grow in their

gardens. It is now known that many of the most beneficial

phytonutrients have a bitter, sour or astringent taste. Second,

early farmers favored plants that were relatively low in fiber and

high in sugar, starch and oil.

These energy-dense plants were

pleasurable to eat and provided the calories needed to fuel a

strenuous lifestyle. The more palatable our fruits and vegetables

became, however, the less advantageous they were for our health.

And as farmers strain to feed ever more

mouths in the face of environmental change, the problem may become

worse.

Last year, researchers at Harvard University warned that

crops grown in the future

will have significantly less zinc

and iron, due to rising levels of carbon dioxide from fossil fuel

use.

The team grew 41 different types of

grains and legumes, including wheat, rice, maize, soybeans and field

peas, under CO2 levels crops are likely to experience 40 to 60 years

from now. They found that under these conditions, wheat had 9 per

cent less zinc, 5 per cent less iron and 6 per cent less protein

than a crop grown at today's CO2 levels.

Zinc and iron - but not protein - were

also lower in legumes grown under elevated CO2.

A 2003 study evaluated the nutritional

content of

broccoli kept in conditions

that simulated commercial transport and distribution:

film-wrapped and stored for seven days at 1°C,

followed by three days at 15°C to replicate a retail environment.

By the end, the broccoli had lost between 71 and 80 per cent of its

glucosinolates - sulphur-containing compounds shown to have

cancer-fighting properties - and around 60 per cent of its

flavonoid antioxidants.

Many kinds of mass-produced fruit and

veg - most famously tomatoes - are picked unripe so that they bruise

less easily during transit. They are then sprayed with ethylene to

ripen them.

Some studies suggest that

tomatoes harvested early have lower

antioxidant activity and less flavor.

"If a fruit is left on a plant until

the end of its life cycle, it's able to recycle all the energy

from the plant," says Wagstaff. "If you pick it early you

truncate that process and get less sugars into the fruit, which

are needed to bind the nutrients."

Supermarket tomatoes are often labeled

as "vine-ripened", but that doesn't always mean what you hope, she

says.

"It may be ripened on the vine but

the vine may not have been attached to the plant."

However, Wagstaff stresses that the

downsides of early picking are small and an unavoidable consequence

of consumer demand.

"If you pick a tomato that you have

grown at home, it tastes fabulous because it's absolutely ready

to eat," she says.

"But there's no way you could do

that at a commercial level because of the bruising that would

occur if ripe fruits were transported through a typical supply

chain. There has to be a compromise somewhere."

Another complication is that each method

of shipping and storing foods has different effects on the compounds

they contain.

Vitamin C, for example, breaks down in

the dark, whereas glucosinolates - found in vegetables like broccoli

and cabbage - deplete in the light.

"That's one of the problems with

horticulture," says Wagstaff. "By its very nature you have an

enormous diversity of genera and species. In an ideal world,

each one would have a tailored supply chain."

Peas can lose half of their vitamin C in

the first 48 hours after harvesting, but if frozen within 2 hours of

picking they retain it.

"Frozen peas are much more

nutritious than peas you buy ready to shell," says Catherine

Collins, principal dietician at St George's Hospital in London.

What's more, frozen foods often have

fewer additives.

"Freezing is a preservative," she

says. "Any loss of nutrients must be weighed against the fact

that these products may encourage people to eat better overall"

Similarly, processing has become a

maligned word in the context of food, but there are some cases where

it enhances a food's health benefits. In fact, you arguably get more

benefits from processed tomatoes, such as in purees, sauces or ready

chopped in cans, than fresh.

Although salad leaves that have been

picked and stored for several days before being eaten are

a bit less nutritious than a

freshly harvested lettuce, chilling

and using packaging to reduce oxygen exposure

may slow the nutrient loss.

And any loss of nutrients must be

weighed against the fact that these products may encourage people to

eat better overall.

"There is a chance that ready

prepared vegetables may have a lower content of some vitamins,"

says Judy Buttriss, director general of the British Nutrition

Foundation in London.

"But if their availability means

that such vegetables are consumed in greater quantities, then

the net effect is beneficial."

The bottom line is that although aspects

of today's food production, processing and storage might make what

we eat a bit less nutritious, they are also making foods more

available - and this is far more important.

The majority of us

consume far less fruit and vegetables than we ought to.

We eat too much fat, sugar and salt and

not enough oily fish.

"The most important thing you can do

is eat more fruits, vegetables and wholegrains, and cut down on

highly refined, human-made foods, vegetable oils and added

sugars," says Davis.

"If you're worrying about nutrient

losses from cooking or whether your food is straight from the

farm - those differences are minor compared to the differences

you'd get from eating unprocessed foods."

What's

really on your plate

How

have modern farming methods affected the nutrients in common

foods?

Beef

Beef from cattle reared outdoors on grass

is less fatty and contains more omega-3 fatty acids

than cattle reared indoors and fed mainly grain. However,

consumers preferred the taste of latter, according to a 2014

study.

Pasta

Today's pasta might be less

nutritious thanks to modern,

fast-growing wheat varieties

introduced in the 1960s. Levels of zinc, iron and magnesium

remained constant in wheat grain from 1865 to the mid-1960s,

then decreased significantly as yields shot up.

Carrots

Carrots from the 1940s

contained less than half

the vitamin A levels of carrots grown in the US 50 years

later. The reason? A preference

for more orangey carrots. The color comes mainly from the

pigment beta-carotene, which the body can use to make

vitamin A.

Milk

Milk from cows reared the

old-fashioned way - mainly feeding on grass outdoors - has a

better nutritional profile

of proteins, fatty acids and antioxidants than milk from cows reared indoors and fed

intensively.

Bread

Humans have been making bread for 10,000 years, but the way

we do it

has changed dramatically in the last half-century.

In 1961, a new method of

mass-producing bread was devised at the Chorleywood

laboratories, just north of London. It used extra yeasts,

additives called processing aids and machinery to slash

fermentation times, so a loaf could be made in just a few

hours.

Around 80 percent of bread consumed is now made this

way.

But there are concerns that such

methods have altered the digestibility of bread, and this

may explain why many people with irritable bowel syndrome

and gluten sensitivity name bread as a trigger. For a

significant subset of those with IBS, the condition is

thought to be linked to gut bacteria reacting to fermentable

foods, causing gas and bloating.

Last year, Jeremy Sanderson at

King's College London and colleagues

compared the effects of

fast and slow-fermented breads

on gut microbiota from donors with IBS and those free from

it. They found that sourdough bread - which is left to rise

for several hours using its natural yeasts - produced

"significantly lower cumulative gas" in the IBS donors'

microbiota than fast-fermented bread.

The theory is that if bread is

left to ferment for longer, its carbohydrates will reach the

gut in a predigested state and gut bacteria won't react so

much.

"If you under-ferment bread

and add a lot of yeast, it's hardly surprising this will

set up problems for people who have a problem with

fermentation in their gut," says Sanderson.

Slow-fermented breads may

benefit other groups too: sourdough produces a lower glucose

response in the body than other breads. What's not yet clear

is whether eating slow-fermented breads would lead to a

general improvement in the gut flora of healthy people.

"That's difficult, but it's

a reasonable hypothesis," says Sanderson. "After all,

bread-making probably evolved to match what the gut

could cope with."

If modern, high-intensity farming is

causing food to lose some of its goodness, could organic food

offer an alternative?

For many consumers the answer is

yes...

Sources

|