|

8 August 2012

A new species of human: One of several co-existing in Africa two million years ago

Anthropologists have discovered three human fossils that are between 1.78 and 1.95 million years old.

The specimens are of a face and two

jawbones with teeth.

The human lineage Instead, according to Dr Meave Leakey of the Turkana Basin Institute in Nairobi, who led the research the find shows that there was a diversity early on in the evolution of our species.

In other groups of animals many

different species evolve, each with new traits, such as plumage, or

webbed feet. If the new trait is better suited to the environment

then the new species thrives, if not it becomes extinct.

According to Dr Leakey, the growing body of evidence to suggest that humans evolved in the same way as other animals shows that "evolution really does work".

by Adam Van Arsdale

from

Wellesley Website

This is a critical time period in human evolutionary history, as it corresponds to the early evolution of our genus, Homo. The article has gotten a lot of attention, with stories in the New York Times, two related commentaries in Nature, and I am sure numerous other stories elsewhere.

I am not sure if the actual article is behind a firewall or not, but here is the abstract:

Indeed, these are wonderful new fossils, particularly the KNM-ER 62000 lower face and KNM-ER 60000 mandible.

Writing for Scientific American, Kate

Wong has a nice commentary on the story that includes several

quotes from me, which I thought I could clarify and expand on a bit.

What makes me so crazy?

To explain, it helps to have a little

historical perspective on the “problem” of early Homo.

When the original Olduvai material was discovered it showed a combination of characters that appeared intermediate between already known South African Australopiths (A. africanus, in particular) and already known Asian (and to a less extent, African) Homo erectus such as those from China and Java.

Philip Tobias, controversially, gave them the designation Homo habilis and placed them as a transitional species. Over time a lot more fossils from this 1.5-2.0 time period were discovered, and rather than clarifying the set of relationships, these new fossils simply added more and more variation to the picture.

This is particularly true for the huge number of fossils uncovered by researchers in the Turkana/Omo basin region of Northern Kenya and Southern Ethiopia (e.g. KNM ER-1470, KNM WT-15000, KNM ER-3733, KNM ER-992, KNM ER-1813, KNM ER-1805 and many many more).

As a result, Homo habilis, which was already rather poorly defined on the basis of features that don’t preserve well (hand morphology), are highly variable (cranial capacity, dentition size), or non-morphological (tool use), began to be viewed as representing multiple taxa.

Instead of representing a transitional lineage, it came to be viewed more and more as a radiation, and the primary question of interest became how many species (Habilis?, Rudolfensis?, Ergaster?, Erectus?) and which one ultimately led to us. I had the opportunity to view most of these fossils in Nairobi in 2004 while doing my dissertation research.

Indeed, while I was there, Meave Leakey

and Fred Spoor were doing work on earlier published materials for

Ileret, and were very kind and gracious to me in talking about their

work and my own dissertation research.

Dmanisi, although 2000 miles away in Georgia, is positioned smack in the middle of this critical time sequence (~1.76 Ma), but comes from a single, rapidly deposited locality, with fantastic preservation of multiple individuals and partial skeletons. And what is interesting about Dmanisi is the tremendous morphological variation present in an isolated sample.

At Dmanisi we see an echo of the larger

pattern of variation in the East African record, but on a smaller,

more interpretable scale.

Prior to the publication of KNM ER-60000, the Dmanisi 2600 mandible was truly exceptional in many respects relative to other mandibles assigned to early Homo.

In particular, the size of its corpus and height of its ramus stood out.

This new specimen from Kenya, dating from a similar time, is the best match we have yet for its features. And yet it is being linked to a fossil, KNM ER-62000, that has notable affinities (despite a significant difference in size) with KNM ER-1470, a fossil that prior to this publication also appeared somewhat morphologically exceptional relative to its peers.

The authors also note similarities between the new lower face (KNM ER-62000) and the Dmanisi 2700 individual.

So in some ways, these fossils seem to

be filling in a gap between earlier African material associated with

habilis/rudolfensis and Dmanisi. And yet Dmanisi has already been

widely associated with later African and Asian material assigned to

Homo erectus, hence the description of it in various publications as

basal Homo erectus.

This line or argument reminds me of my previous thoughts on the conflation of simplicity with taxonomic linearity in paleoanthropology.

I do not think rapid evolutionary change within a lineage need necessarily be “simple.” We actually have a great model for thinking about this… ourselves.

The last 100,000 years of human evolution involves fairly rapid evolutionary change. This is true for the hard-tissue elements of our anatomy that preserve as fossils, but even more so for our DNA. Yet this rapid evolutionary change was in no ways simple.

It involved a massive and rapid

expansion of human populations out of Africa, significant reductions

in human adult mortality, a diversification and intensification of

human technological production and use AND genetic exchange with at

least distinct and extinct human lineages, the Neandertals and

Denisovans.

Thus, the presence of taxonomic

diversity is already one element present to contribute potential

evolutionary complexity.

Between 2.0 and 1.5 million years there is a significant change, even within specimens that consensus assigns to a single taxon (i.e. Homo erectus) in the form of changing proportionality in the post-cranial skeleton, cranial expansion, reduction in post-canine dental size and related changes in the face and cranial base.

One might conceptualize this as a fairly

rapid change from something that is ecologically distinct from

living humans and apes, whatever the progenitor of Homo is, to

something that has all the trappings of a nascent ecological human

(technologically-mediated, cooperative, ecological generalist).

It is quite possible that Bernard

Wood is correct and we will look back in fifty years and say we

had far too simple a perspective on issues of this time. However, it

is not entirely clear to me that such a view necessitates the

presence of multiple

taxa, overlapping in range,

morphology and ecology.

But for now I will pause and commend the

whole team responsible for providing us with these great new

fossils.

Notes

August 9, 2012

from

Evoanth Website Homo habilis is the earliest member of our genus, living from 2.3-1.4 million years ago.

It was the first species to use stone tools and the first to really look more human than ape, with a face that didn’t stick out anywhere near as far as chimps’ or Australopthecines’. However it isn’t directly related to us. Instead it was a sister species which ultimately died out, like the Neanderthals or Paranthropines.

This means that the early history of the

genus Homo is quite complex since the human lineage must exist

somewhere, along with any other branches H. habilis was related to.

Although several potential H. rudolfensis fossils have been found over the years, few can definitely be placed within the skull’s family.

This lack of data, combined with the

similarities between the skull and H. habilis has resulted in many

debates over whether the H. rudolfensis finds are an entirely new

species or simply an example of variation within H. habilis.

They’re practically an evolutionary

anthropology institution, uncovering the first evidence of the

Oldowan industry, the first Paranthropine and Turkana boy, amongst

many other things.

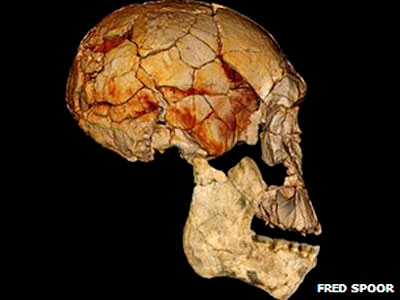

Homo rudolfensis

(right) and Homo habilis (left) The first fossil died ~1.9 million years ago and is a juvenile, about as developed as a 13/14 year old modern human.

However, the life history of these

hominins was shorter so this individual was likely younger than

comparable modern humans, probably around 8 years old. Although most

teeth were missing, there were sufficient to provide an estimate of

the age range for this fossil. Like the teeth, most of the bones

themselves are also missing and all that’s left is the upper jaw and

a portion of the face.

The researchers estimated what it would look like as an adult to circumvent this problem, although that does introduce a potential margin for error. Their predictions place this specimen within the genus Homo, having a flatter “human” like face than Australopithecines. The fossil itself also attests to this conclusion, being more similar to Homo finds, particularly the few juvenile ones available.

Most interestingly, it contains the same

features which sets the original H. rudolfensis skull apart from H.

habilis.

The juvenile fossil The second fossil is a lower jaw, one side of which is particularly well preserved.

From this well preserved side they were able to work out what the other side looked at, removing essentially all errors that any damage would cause. The find itself dates to between 1.87 and 1.78 mya, making it younger than the juvenile. As such, questions are immediately raised over whether it belongs to the same species as the juvenile.

Particularly given that there are a few

differences between the two specimens.

It turns out that despite the aforementioned differences, this fossil does appear to be most similar to the juvenile described above, which in turn is most similar to the original H. rudolfensis skull.

The final fossil is a lower jaw fragment dating to ~1.9 mya.

Like the second fossil, it is most

similar to the juvenile and so is also probably a member of H.

rudolfensis.

The second and third

(fragment in the bottom right) fossils. Most news outlets have claimed that these fossils are the discovery of some new species.

However, as I mentioned, the original H. rudolfensis cranium is nearly 40 years old! This find can hardly be categorized as a new species. A more accurate headline would be “New fossils confirm suspected species exists.”

Although the truth is less snappy I do not believe that justifies ignoring it.

But before I go writing letters to

newspapers demanding corrections, do these fossils in fact confirm

H. rudolfensis was a real, distinct species? Although they can

clearly be grouped with the original cranium, does that indeed lend

credence to placing this group outside of Homo habilis?

Whilst a point in favor of H. rudolfensis being distinct, it is not conclusive proof.

That must come from the anatomy, from

figuring out whether these creatures are different enough to be

defined as a different species. Ultimately the number of examples of

anatomy is moot, so the fact we’ve found more fossils is not

conclusive proof.

Although these finds might not be as crucial as newspapers say they are (one even reporting this “rewrites the story of human evolution“) these finds are still very important.

What we label a species is not that important. We now know that there was definite, population wide variation within early Homo and that the story of our genus’s genesis (try saying that after a few pints) is even more complex than the single cranium suggested.

It might not “rewrite” the story, but it is certainly editing a chapter.

|