|

June 01, 2017

from

MessageToEagle Website

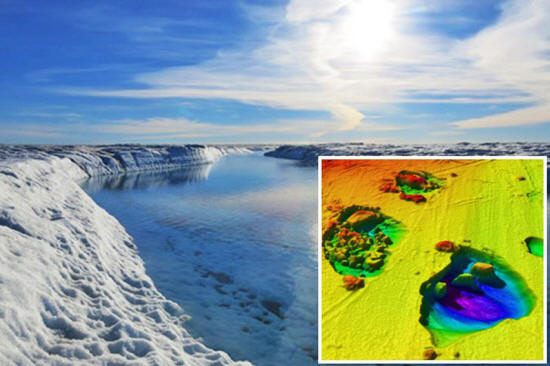

The Siberian craters are small in comparison to these giant methane

"monsters" that have been discovered on the Arctic Sea floor.

Methane, a potent greenhouse gas is

still leaking in large amounts from the enormous craters that formed

about 12,000 years ago.

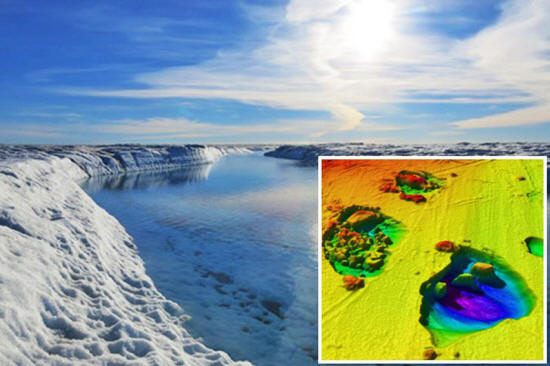

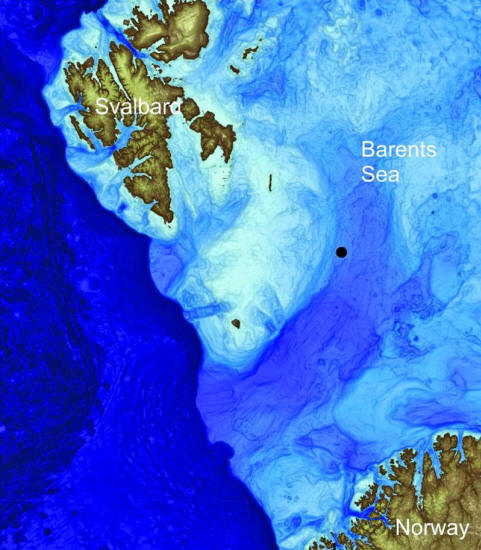

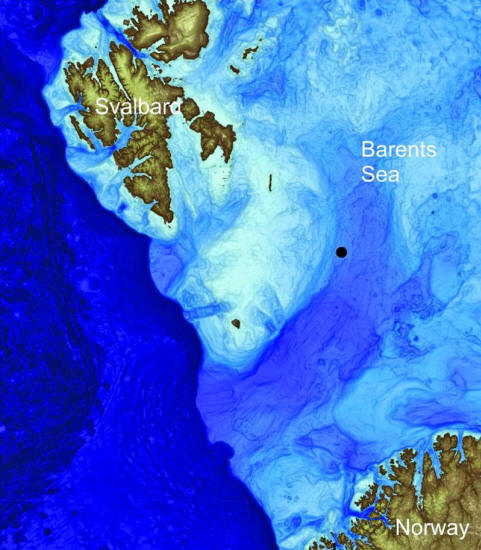

The Barents Sea,

where

the team found and studied the craters.

K. ANDREASSEN/CAGE

"The crater area was

covered by a thick ice sheet during the last ice age, much as

West Antarctica is today. As climate warmed, and the ice sheet

collapsed, enormous amounts of methane were abruptly released.

This created massive

craters that are still actively seeping methane" says Karin

Andreassen, first author of the study (Massive

Blow-Out Craters formed by Hydrate-controlled Methane expulsion

from the Arctic Seafloor) and professor at

CAGE 'Centre for Arctic Gas

Hydrate, Environment and Climate.'

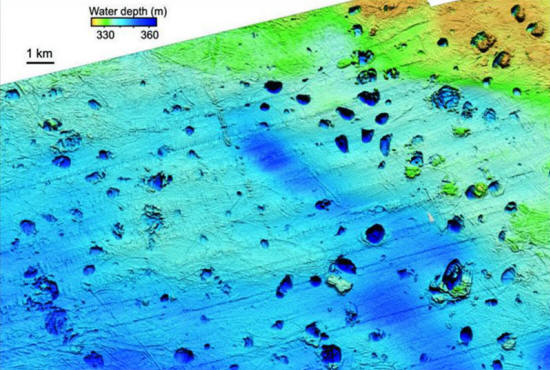

Over 100 of the

Methane Craters Are Up To One Kilometer Wide

A few of these craters were first observed in the 90-ties.

However, using new

researchers were able to discover that the craters cover a much

larger area than previously thought. Over one hundred of the methane

craters are up to one kilometer wide.

In comparison, the huge blow-out craters on land on the Siberian

peninsulas

Yamal and

Gydan are 50-90 meters wide, but

similar processes may have been involved in their formation.

Giant

sinkhole in Siberia

The new Yamal crater is in the area's Taz district

near

the village of Antipayuta and has

a

diameter of about 49ft (15 meters).

Read more

The Arctic ocean floor hosts vast amounts of methane trapped as

hydrates, which are ice-like, solid

mixtures of gas and water.

These hydrates are stable under high pressure and cold temperatures.

The ice sheet provides perfect conditions for subglacial gas hydrate

formation, in the past as well as today.

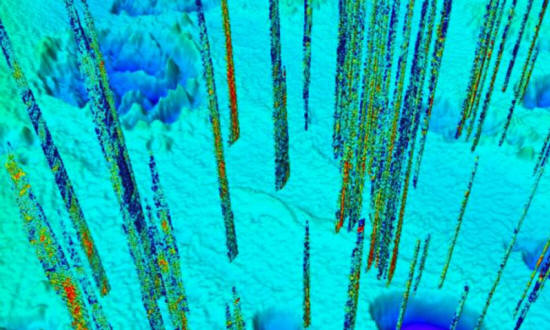

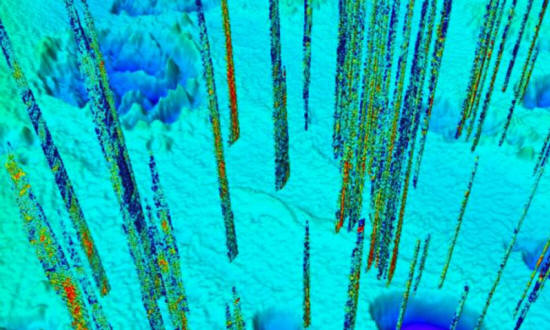

Today more than 600 gas flares are identified in and around these

craters, releasing the greenhouse gas steadily into the water

column. Researchers say it's nothing compared to the blow-outs of

the greenhouse gas that followed the deglaciation.

The amounts of methane

that were released must have been quite impressive.

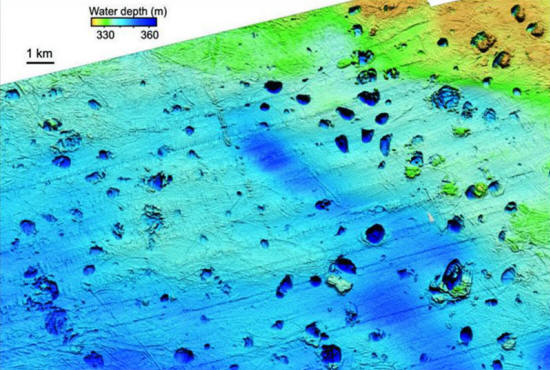

There are several hundred craters

in the

area the study looked at.

Over

one hundred of them

are up

to 1,000 meters wide.

Some 2000 meters of ice loaded what now is ocean floor with heavy

weight. Under the ice, methane gas from deeper hydrocarbon

reservoirs moved upward, but could not escape.

It was stored as gas

hydrate in the sediment, constantly fed by gas from below, creating

over-pressured conditions.

"As the ice sheet

rapidly retreated, the hydrates concentrated in mounds, and

eventually started to melt, expand and cause over-pressure.

The principle is the

same as in a pressure cooker:

if you do not

control the release of the pressure, it will continue to

build up until there is a disaster in your kitchen.

These mounds were

over-pressured for thousands of years, and then the lid came

off.

They just collapsed

releasing methane into the water column" says Andreassen.

Similar

Processes Are Ongoing Under Ice Sheets Today

Major methane venting events such as this appear to be rare, and may

therefore easily be overlooked.

The massive craters were formed around 12,000 years ago,

but are

still seeping methane and other gases.

Credit:

Andreia Plaza Faverola/CAGE

"Despite their

infrequency, the impact of such blow-outs may still be greater

than impact from slow and gradual seepage.

It remains to be seen

whether such abrupt and massive methane release could have

reached the atmosphere. We do estimate that an area of

hydrocarbon reserves twice the size of Russia was directly

influenced by ice sheets during past glaciation.

This means that a

much larger area may have had similar abrupt gas releases in the

overlapping time period" says Andreassen

Another fact to consider

is that there are reserves of hydrocarbons beneath the load of West

Antarctica and Greenland ice sheets today.

"Our study provides

the scientific community with a good past analogue for what may

happen to future methane releases in front of contemporary,

retreating ice sheets" concludes Andreassen.

|