|

by Erika Check Hayden

12 October 2016

from

Nature Website

Spanish version

Why many 'deadly' gene

mutations

are turning out to be harmless.

Lurking in the genes of the average person are about 54 mutations

that look as if they should sicken or even kill their bearer. But

they don't. Sonia Vallabh hoped that D178N (PrP

gene) was one such

mutation.

In 2010, Vallabh had watched her mother die from a mysterious

illness called 'fatal familial insomnia,' in which misfolded

prion

proteins cluster together and destroy the brain.

The following year, Sonia was tested and

found that she had a copy of the

prion-protein gene, PRNP, with the

same genetic glitch - D178N - that had probably caused her mother's

illness. It was a veritable death sentence: the average age of onset

is 50, and the disease progresses quickly.

But it was not a sentence that Vallabh,

then 26, was going to accept without a fight.

So she and her husband, Eric Minikel,

quit their respective careers in law and transportation consulting

to become graduate students in biology.

They aimed to learn everything they

could about fatal familial insomnia and what, if anything, might be

done to stop it. One of the most important tasks was to determine

whether or not the D178N mutation definitively caused the disease.

Few would have thought to ask such a question in years past, but

medical genetics has been going through a bit of soul-searching. The

fast pace of genomic research since the start of the twenty-first

century has packed the literature with thousands of gene mutations

associated with disease and disability.

Many such associations are solid, but

scores of mutations once suggested to be dangerous or even lethal

are turning out to be innocuous.

These sheep in wolves' clothing are

being unmasked thanks to one of the largest genetics studies ever

conducted:

the Exome Aggregation Consortium, or

ExAC.

ExAC is a simple idea. It combines sequences for the protein-coding

region of the genome -

the exome - from more than 60,000 people into

one database, allowing scientists to compare them and understand how

variable they are.

But the resource is having tremendous

impacts in biomedical research. As well as helping scientists to

toss out spurious disease-gene links, it is generating new

discoveries.

By looking more closely at the frequency

of mutations in different populations, researchers can gain insight

into what many genes do and how their protein products function.

ExAC has turned human genetics upside down, says geneticist David

Goldstein of Columbia University in New York City.

Instead of starting with a disease or

trait and working backwards to find its genetic underpinnings,

researchers can start with mutations that look like they should have

an interesting effect and investigate what might be happening in the

people who harbor them.

"This really is a new way of

working," he says.

ExAC is also providing

better information for families facing genetic diagnoses.

D178N, for example, was strongly

suspected of causing prion disease because it had been seen in

several people with the condition and seldom elsewhere. But before

ExAC, no one really had the power to see just how rare it was.

If it shows up in people more frequently

than prion disease does, that would mean Vallabh's risk of getting

the disease is much lower than predicted.

"We needed to find out if this

mutation had ever been seen in a healthy population," Minikel

says.

Data gathering

ExAC was born of frustration.

In 2012,

geneticist Daniel MacArthur was starting his first

laboratory, at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston.

He wanted to find genetic mutations that

caused rare muscle diseases, and needed two things:

If a mutation was more common in people

with a disorder than in healthy controls, it stood to reason that

the mutation was a likely cause.

The problem was that MacArthur couldn't

find enough sequences from unaffected people. He needed lots of exomes, and although researchers had been sequencing them by the

thousands, existing data sets weren't large enough.

No one had pulled enough together into

one combined, standardized resource.

|

Daniel

MacArthur convinced researchers

to share

genetic data on tens of thousands of people.

Sam Goresh

for Nature

|

So MacArthur started asking his

colleagues to share their data with him.

He was well suited to the task:

an early adopter of social media,

his lively blog posts and acerbic Twitter feed had made him

unusually popular and authoritative for a young scientist.

He also had a position with the

Broad

Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts, a genome-sequencing

powerhouse.

MacArthur convinced researchers to share

data from tens of thousands of exomes with him; most were in some

way connected to the Broad.

All that remained was to analyze the

data, but that was no trivial task. Although the genes had been

sequenced, the raw data had been analyzed using different types of

software - including some that were out of date.

If one individual in the collection

showed a rare mutation, it could be real - or it could be an

artifact of how different programs 'called' the bases within,

judging whether they were,

MacArthur needed something that would

standardize this gigantic data set. The Broad had developed

genome-calling software, but it wasn't up to the task of churning

through the tremendous amount of data included in ExAC.

So MacArthur's team worked closely with

the Broad programmers to test the software and scale up its

abilities.

"That was a pretty horrific 18

months," MacArthur recalls. "We ran into every obstacle

imaginable and had nothing to show for it."

Personal stake

While this was going on, in April 2013,

Vallabh was learning how to work with stem cells at MGH while

Minikel studied bioinformatics.

Minikel met MacArthur for lunch and

explained his and Vallabh's curiosity about whether D178N existed in

healthy people. He admits to being a bit star-struck by MacArthur's

reputation.

"I thought if I could get him to

think about my problem for half an hour, that would probably be

the most important thing that happened in my whole month,"

Minikel says.

The pair went upstairs to MacArthur's

lab, where bioinformatician Monkol Lek ran a search on the ExAC data

that had been analyzed so far - about 20,000 exomes.

They didn't see Vallabh's mutation. That

wasn't good news, but, optimistic about exploring the data further,

Minikel joined MacArthur's lab.

By June 2014, MacArthur's team and its

collaborators had a data set that they were confident in - exomes

from 60,706 individuals representing various ethnic groups, who met

certain thresholds for health and consent.

They released ExAC that October at the

annual meeting of the American Society of Human Genetics (ASHG), in

San Diego, California. Immediately, researchers and physicians

recognized that the data could help to recast their understanding of

genetic risks.

Many disease-association studies,

particularly in recent years, have identified mutations as

pathogenic simply because scientists performing analyses on a group

of people with a disorder found mutations that looked like the

culprit, but didn't see them in healthy people.

But it's possible that

they weren't looking hard enough, or in the right populations.

Baseline 'healthy' genetic data has tended to come mainly from

people of European descent, which can skew results.

In August this year, MacArthur's group

published 1 its analysis of ExAC data in Nature,

revealing that many mutations thought to be harmful are probably

not.

In one analysis, the group identified

192 variants that had previously been thought to be pathogenic, but

turned out to be relatively common. The scientists reviewed papers

about these variants, looking for plausible evidence that they

actually caused disease, but could find solid evidence for only nine

of them.

Most are actually benign, according to

standards set by the American College of Medical Genetics and

Genomics (ACGM), and many have now been reclassified as such.

Similar work promises to have direct

impacts on medical practice.

In a companion paper, 2

geneticist Hugh Watkins of the University of Oxford, UK,

looked at genes associated with certain types of cardiomyopathy that

cause gradual weakening of the heart muscle.

Undetected, they can lead to sudden

death, and it has become fairly common to check relatives of people

with the conditions for genetic mutations associated with them.

Those found to have a genetic risk are

sometimes counseled to get an implanted defibrillator, which

delivers electrical shocks to the heart if it seems to be beating

abnormally.

Watkins checked the ExAC database for

information on genes that have been associated with these heart

conditions, and found that many mutations are much too common among

healthy people to be pathogenic.

About 60 genes had been implicated as

harboring pathogenic mutations that cause one form of the disease;

Watkins' analysis revealed that 40 of these probably bear no link.

This was troubling.

"If you have a genetic risk that you

believe is predicting disease but isn't, you can end up doing

drastic things that can harm someone," says Watkins.

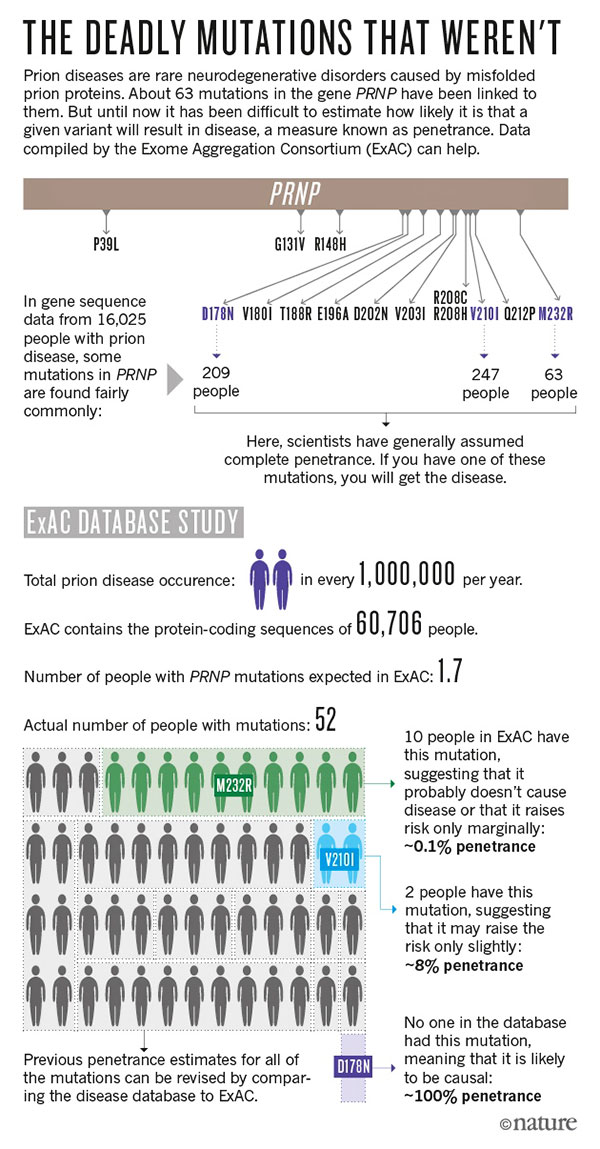

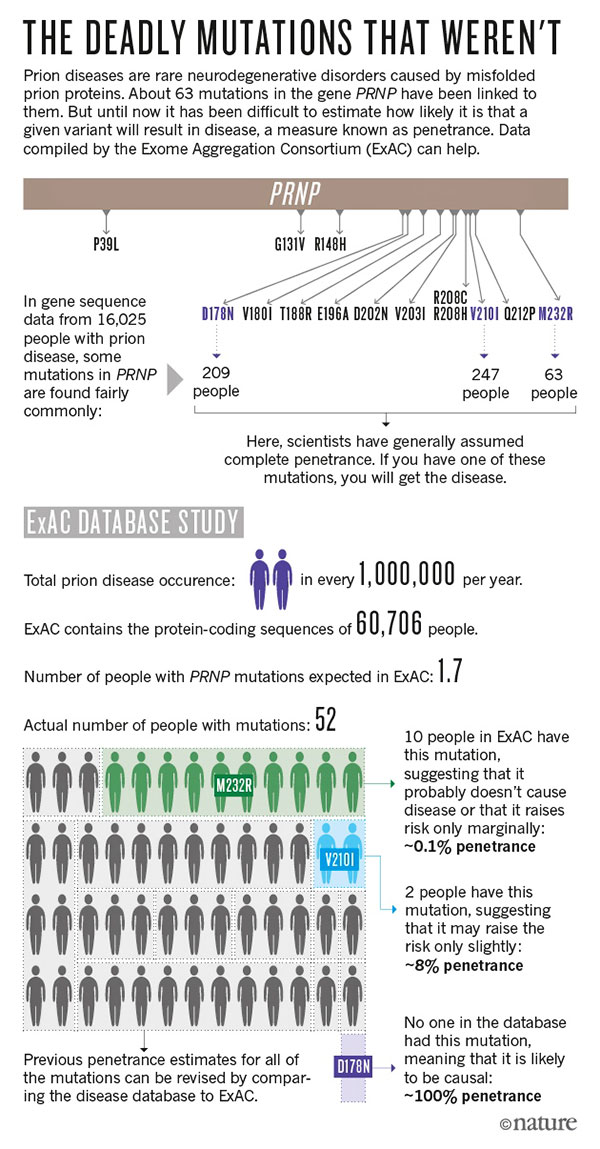

Even some of the mutations that seem to

be reliably linked to disease aren't a sure bet - such as those in

PRNP.

There are definitely mutations in the

gene that cause the disease, but some variants might not be

pathogenic or might elevate the risk only slightly (see

'The Deadly Mutations that Weren't').

To find out the status of D178N, Vallabh

and Minikel gathered genetic data from more than 16,000 people who

had been diagnosed with prion diseases, and compared them with data

from almost 600,000 others, including the ExAC participants.

3

The pair found that 52 people in ExAC

had PRNP mutations that have been linked to prion diseases,

but based on the prevalence of the disease, they would have expected

to see maybe two.

Minikel calculated that some of these

supposedly lethal mutations elevated a person's risk of prion

disease slightly; some seemed not to be linked to prion disease at

all.

This work provided insight for people

such as Alice Uflacker.

In 2011, Uflacker's father, Renan, died

from

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, a prion illness that causes rapid

mental and physical deterioration. He was 62. Alice found out that

she carried a mutation in PRNP called V210I, which had been

linked to her father's disease in previous studies.

Three years later, she learned from

Minikel that the mutation confers, at most, a small risk of disease.

The information was helpful, and the result made sense; her

grandmother had lived to 93 despite having the same mutation.

Vallabh and Minikel would find no such

relief, however. D178N was absent from the other genomes they looked

at, and is still highly likely to cause prion disease.

Minikel and Vallabh had already begun to

suspect as much, as Minikel dug into the data.

"All along the way was gradual

confirmation of what we were assuming anyway," Minikel says.

"There wasn't any moment where we said, 'Ah, this is the worst

news.' We'd already gotten the worst news."

Human knockouts

ExAC is revealing a lot about genes

through the frequency of mutations.

MacArthur and his team found 1

3,200 genes that are almost never severely mutated in any of the

ExAC genomes - a signal that these genes are important. And yet 72%

of them have never before been linked to disease. Researchers are

eager to study whether some of these genes play unappreciated parts

in illness.

Conversely, the group has found nearly

180,000 instances of mutations so severe that they should render

their protein products completely inactive. Scientists have long

studied genes by knocking them out in animals such as mice, so that

they don't work.

By looking at the symptoms that develop,

they can study what the genes do. But that has never been possible

in humans.

Now, researchers are eager to study

these natural human knockouts to understand what they can reveal

about how diseases develop or may be cured. MacArthur and other

researchers are gearing up to prioritize which human knockout genes

to study and how best to contact the people carrying them for

further study.

But it will have to wait until he

completes the second phase of ExAC.

Due to be unveiled at the ASHG

meeting in Vancouver, Canada, this month, it will double the

data set's size to 135,000 exomes and include some 15,000

whole-genome sequences, which should allow researchers to

explore mutations in regulatory regions of the genome that are

not captured by exome sequencing.

ExAC is quietly becoming a standard

tool in medical genetics.

Clinical labs around the world now

check it before telling a patient that a particular glitch in

their genome might be making them ill. If the mutation is common

in ExAC, it's unlikely to be harmful.

Geneticist Leslie Biesecker

at the US National Human Genome Research Institute in Bethesda,

Maryland, says that his lab uses ExAC daily in patient care.

"It's a critical factor that we

take into consideration for every variant," he says.

He and other geneticists are now

embarking on a

painstaking reckoning with the genetics literature that will

probably take years.

ExAC has also driven home a point

that Goldstein and other researchers have made repeatedly:

that

failing to include people from Asian, African, Latino and other

non-European ancestries is holding back understanding of how

genes influence disease by

limiting the view of human genetic diversity.

There is now a fresh impetus to

include under-represented groups in planned studies linking

genetics and health information on large numbers of people, such

as the

US Precision Medicine Initiative.

For Vallabh and Minikel, ExAC

provided a disheartening confirmation, but also some promising

insight.

Minikel's studies have identified

3 three people in ExAC with mutations that should

silence one of the two copies of the prion protein gene. If they

can live with a limited amount of functioning protein, perhaps a

drug could be made that would silence the defective protein in

Vallabh, preventing prion aggregation and disease progression

without dangerous side effects.

Minikel got in touch with one of the

individuals, a man in Sweden, who agreed to donate some cells

for research.

Minikel and Vallabh have now joined the lab of

biochemist Stuart Schreiber at the Broad Institute, where they

are working full-time to find candidate drugs to treat prion

disease.

The couple exemplifies the challenge

of translating ExAC data into real medical benefits.

"We can't go back from this,"

Vallabh says. "We have to go through it."

Their situation couldn't be more

illustrative of what is at stake: Vallabh is now 32 - just 20

years younger than her mother was when she died.

She has no time to waste.

References

1. Lek, M. et al. Nature 536,

285-291 (2016) -

Analysis of Protein-Coding Genetic

Variation in 60,706 Humans.

2. Walsh, R. et al. Genet. Med. (2016) -

Reassessment of Mendelian Gene

Pathogenicity Using 7,855 Cardiomyopathy Cases and 60,706

Reference Samples.

3. Minikel, E. V. et al. Sci. Transl. Med. 8, 322ra9 (2016) -

Quantifying Prion Disease Penetrance Using

Large Population Control Cohorts.

|