|

by Jeff Tollefson

October

05, 2022

Drug trafickers have been spotted using this illegal airstrip on an island in Peru’s Madre de Dios River.

protect themselves

and the world's

largest rainforest?

are rapidly invading the remote Peruvian Amazon, home to isolated people and a wealth of biodiversity. Nature met the researchers and Indigenous communities fighting to stop the destruction.

Tayori collects his gear

and makes his way barefoot up a rocky beach. The low roar of the

Madre de Dios River fills the air as he sets up a drone on a flat

patch of sand.

Tayori is here to check

out reports from local Indigenous communities that drug traffickers

have been using the island as a base.

on an island in the Madre de Dios River.

The Madre de Dios region is a vast landscape that holds massive stocks of carbon and biodiversity, but modernity is quickly encroaching in the form of loggers, gold miners, energy developers and drug traffickers, along with the profound impacts of global warming.

Combined, they create an

existential threat to the Amazon forest and the Indigenous peoples

who live there.

Any kind of contact could be disastrous for these people, who lack immunological defences against modern diseases and have been decimated by respiratory illnesses when they've come into contact with the outside world.

The COVID-19 pandemic

presents yet another threat to these peoples.

Luis Tayori (left) and

his crew.

But after decades of effort, the destruction of the rainforest continues.

Today, scientists,

advocates and policymakers increasingly recognize that achieving

climate and conservation goals won't be possible unless they're

aligned with efforts to help Indigenous communities secure and

protect their territories.

Scientists and

conservationists, together with established Indigenous communities

on the frontier, are working to fill the void with science and

technology.

Along the way, the skiff passes the bullet-ridden wreckage of a plane - all that remains after the Peruvian military ambushed drug traffickers on the beach in 2018.

pieces of white plane wreckage

partially covered by

tree branches.

destroyed by Peruvian

authorities in 2018.

A changed world

Over the course of two weeks, we met scientists and travelled up the Madre de Dios River with Tayori and his team, speaking to government officials and Indigenous people along the way.

Since then, threats to the Amazon have increased, in part because of the pandemic.

At the same time,

scientists interviewed by Nature have made progress in evaluating

technologies and strategies for protecting territories deep in the

jungle.

In September 2021, the International Union for Conservation of Nature voted in favour of a motion from Indigenous groups calling for conservation of 80% of the Amazon by 2025.

Two months later, at the United Nations climate summit in Glasgow, governments and philanthropic organizations committed at least US$1.7 billion over 5 years to help Indigenous peoples claim and protect their lands.

Indigenous leaders meet with Carolina Schmidt (centre, with face mask), who was COP25 president and environment minister for Chile, at the United Nations climate summit in Glasgow, UK, last November.

Credit: Paul Ellis/AFP

via Getty

Halting the relentless onslaught of illegal activity won't be easy, they say, but Indigenous groups are gearing up for the challenge with help from researchers and advocates.

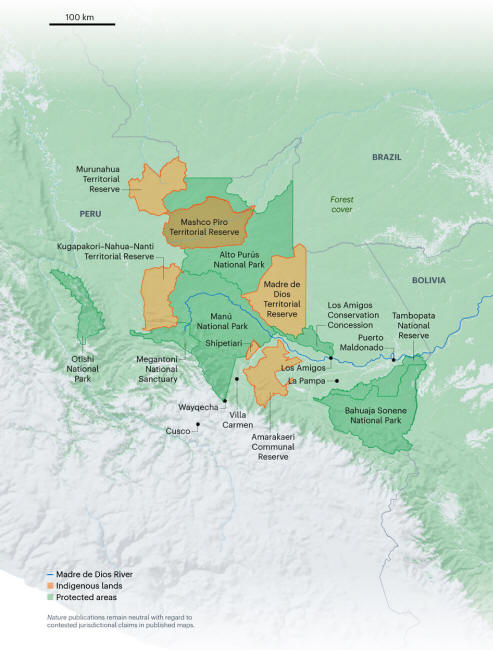

Established in 1973, the park anchors a collection of protected areas and Indigenous reserves larger than Portugal that stretches all the way to the Brazilian border (see ‘An ark of diversity').

To some scientists, the area is an ark of biological, ecological and topographical diversity that might just be large enough to survive the coming climate storm, providing a relatively safe space for the local Indigenous peoples, plants and animal species while humanity figures out how to rein in greenhouse gases.

But this theory works only if Peru is able to safeguard these lands.

Given the scale of the challenge and the government's limited capacity to patrol these vast territories, scientists say that both technology and Indigenous people who live on the front lines will be crucial to protecting the region.

...says Adrian Forsyth, a biologist who has spent the past three years investigating options for protecting what he calls the deep forest, an environment where rain, humidity, clouds and sheer distance from reliable power sources and communications pose challenges for any kind of protection system.

Biologist Adrian Forsyth, stands alone surrounded

by heavy jungle foliage.

Its focus was on protecting the vast and often inaccessible territories that isolated groups call home.

His idea was to convert the deep forest into a smart forest that can detect intruders and relay alerts to government authorities and local Indigenous communities - who he thinks are best positioned to speak on behalf of isolated peoples.

The conference focused on

devices such as microphone and camera systems equipped with

artificial intelligence, as well as data from drones and satellites

that could be deployed remotely.

Such knowledge could be used to minimize potentially devastating contacts and conflicts with intruders - or with anybody who lives and works in areas adjacent to the protected zones where isolated tribes roam.

Questions abound over the use of this technology to monitor people who have opted, out of fear, to shun modern society.

But like many other tropical ecologists and conservationists, Forsyth fears that time is running out for the isolated groups.

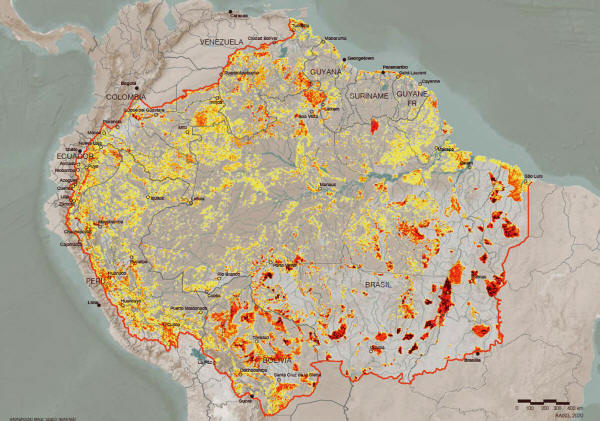

Despite decades of social and environmental campaigns aimed at protecting the Amazon, the threats now are greater than they have ever been, thanks to the relentless expansion of activities such as agriculture, mining, energy development, logging and drug trafficking (see ‘Conserving the Amazon').

Even in Brazil, which was

held up as a model of sustainable development less than a decade

ago,

illegal deforestation is skyrocketing as the populist

government of President Jair Bolsonaro seeks to dismantle

long-standing protections for the environment and Indigenous rights.

In many places, already limited law-enforcement activities ground to a halt at the height of the pandemic, but scientists and Indigenous representatives say that the criminals didn't take a break.

At the same time, the economic downturn made illicit activities, such as mining for gold and cultivating coca plants, all the more enticing for criminal networks and anybody seeking to eke out a living in the forest - Indigenous people included.

...says Bewick, who

stepped down in October 2021 as head of Peru operations at the

Rainforest Foundation US, which has provided more than $5 million

for Indigenous conservation efforts in Peru over the past decade.

Video. Illegal gold mining has transformed a once-forested region in La Pampa, Peru, into a wasteland of sand dunes

and ponds polluted with

mercury. Wake Forest University

Scientists with the

Amazon Network of Georeferenced Socio-Environmental Information (RAISG),

a consortium of advocacy groups across the Amazon, are working with

Indigenous groups to map conservation threats and opportunities

across the region.

But demand for resources,

such as agricultural land, wood, minerals and energy, has led to the

destruction of around 15% of the original rainforest.

As of 2017, around 28% of tropical forests were owned by or designated for Indigenous peoples and local communities globally, according to the Rights and Resources Initiative, an international coalition in Washington DC.

The goal of the

initiative is to increase that figure to at least 50% by 2030.

RAISG has mapped a

spiderweb of more than 96,000 kilometres of roads across the Amazon.

As of 2020, there were 177 hydroelectric plants in operation and

another 184 planned. Research shows that such infrastructure

increases deforestation.

Since 1985, the area

dedicated to agriculture, which is responsible for 84% of Amazonian

deforestation, has tripled. An index developed by RAISG combines human threats to show which areas have been affected the most. A substantial portion of the Amazon

shows signs of

moderate to very high disturbance.

An increasingly vocal and organized Indigenous community has seized on the evidence, arguing that Indigenous rights are crucial to maintaining biodiversity and protecting the climate.

That argument prevailed

at the UN climate summit last November, leading to the record

financial commitment by governments and major philanthropic

organizations to help Indigenous communities promote conservation.

But economic interests and demand for resources often collide with Indigenous interests, she says.

(pictured sat at a table with representatives of the Chakma ethnic group from Bangladesh) a former UN special rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples.

Credit: Annie Line/The New York

Times/Redux/evevine

Flora and Gregorio Perez, whose son was killed in 2015

Things were tranquil when we arrived, but violence erupted there in May 2015, when a 22-year-old resident named Leo Perez was killed by an arrow.

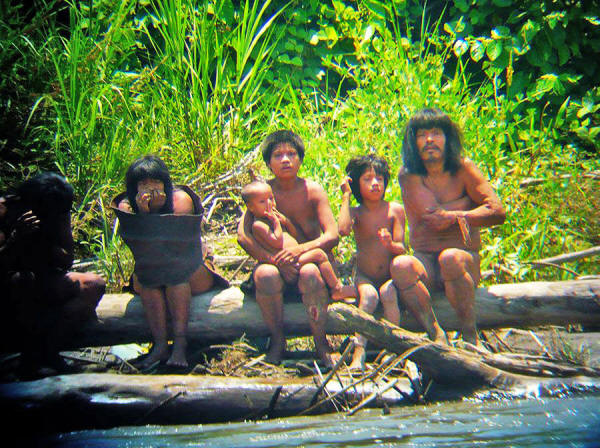

The attack came from an

incursion by members of the isolated Mashco Piro people, who have

been venturing out of the jungle over the past decade, occasionally

coming into conflict with established communities.

But as an evangelical

Christian missionary, he told Nature he urged family members and

fellow villagers not to pursue revenge.

Daniel Rodríguez,

an anthropologist who advises the Native Federation of the Madre de

Dios River and Tributaries (FENAMAD), says the village must have

raided a Mashco Piro camp after the death, because he saw the

resulting loot in Shipetiari.

Although the potential for dangerous conflict remained, teams of villagers, organized and trained by the Peruvian Ministry of Culture, were regularly patrolling the area, with no signs of intrusions.

She and her fellow

villagers worried more about encounters with armed drug traffickers

that roam the area. Nonetheless, she said her community would

retaliate if it were attacked again by the Mashco Piro, some of whom

were regularly appearing on a beach down river.

has a population of 130

people.

Several years earlier,

Mamani said, government anthropologists had been forced to intervene

to defuse a complicated situation created by uncontrolled contact

with tourists, loggers and missionaries.

These communities live in

the forest and are mostly separated from the rest of society, but

sometimes venture into the outside world for a variety of reasons,

whether to barter for food or to take pans and other metal tools.

Most recently, in late

August, the Mashco Piro killed a logger who was fishing with his

friends on the eastern side of their territory - outside the Madre

de Dios reserve that was established to protect the isolated

community.

From time to time, the

Mashco Piro still arrived on the beach offering meat. Ministry

officials might reciprocate with plantains, but try to minimize

their gifts in an effort to prevent dependency.

Once they establish a relationship with ministry personnel, the Mashco Piro often inquire about family members or poke fun if somebody gains weight or cuts their hair.

Some in the ministry had expected that the group was ready to join the outside world, but that has yet to happen.

Rufina Rivera, leader of Shipetiari village, poses for a portrait in Shipetiari village with a building and washing line in the background

Asked about the drug

traffickers' airstrip just minutes upstream from the beach, Mamani

merely shook his head, saying that the ministry doesn't have the

authority to intervene in such matters.

So far, no actions have been taken. When Nature contacted Rivera last month, she confirmed that the drug traffickers - "los narcos" - are still operating from the island, and that the Mashco Piro are still roaming the area.

Scientists suspect that

they went into hiding more than a century ago when the rise of cars

created a rush for Amazonian rubber, which was harvested through a

brutal industry that often relied on enslaved Indigenous people.

The rubber trade wasn't the only threat to people such as the Mashco Piro.

Shepard saw what happened after the company Royal Dutch Shell ploughed roads into the jungle looking for oil northwest of Manú National Park in the early 1980s.

Loggers took advantage of

the roads after the company pulled out, and the end result for one

isolated group, the Nahua, was contact and then disease.

After visiting the group and interviewing survivors in 1996, Shepard calculated that disease wiped out 42% of the population within the first 5 years of contact, but the actual total could be much higher.

Similar stories have played out across the Amazon.

This ultimately pushed

Brazil's National Indian Foundation (FUNAI) to establish a

no-contact policy in the 1980s. That has become the norm in other

countries, including Peru.

guides

a boat upstream.

In addition to working with local Indigenous groups to monitor and control contact, the government has established seven territories for isolated communities, including two last year, and at least three more are in the works.

Designed to protect an estimated 5,000 people who are either living in isolation or who have recently entered into contact with the outside world, these territories cover an area larger than Ireland.

sat on a fallen tree pictured

with a long distance camera lens.

At the time of our visit, officials with Peru's culture ministry acknowledged the challenge of protecting 2.6 million hectares of territorial reserve in the Madre de Dios region alone with only a few dozen field agents.

They said they were

exploring how science and technology could help.

Improving understanding of their locations and movements could help the government to predict where encounters are most likely to occur - and hopefully prevent them.

The ministry has also

partnered with the Association for the Conservation of the Amazon

Basin (ACCA), an activist organization in Lima that was co-founded

by Forsyth, to assess the legal and ethical issues that arise from

the use of any technology to study people who have decided to live

in isolation.

speaking at a scientific conference at the Los Amigos research station, Peru.

Over the course of nearly two decades with the Andes Amazon Fund, he helped to direct hundreds of millions of dollars from philanthropic organizations such as the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, based in Palo Alto, California, to support social, environmental and Indigenous groups as well as academic research and government conservation programs in Peru.

One success was the establishment, in 2000, of a 146,000-hectare property on the Los Amigos River that is owned by the federal government but managed by the ACCA and dedicated solely to science and conservation.

over the rainforest. (This video contains no dialogue,

the sound of the drone's motor can be heard.)

With funding from the

Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, Forsyth has since doled out

grants totaling around $2.4 million dollars to develop these

technologies.

Topher White, the founder of Rainforest Connection, a conservation technology company in Katy, Texas, tested a solar-powered monitoring system at Los Amigos, featuring cellular listening devices on trees and signal repeaters on a pair of research towers.

The system can identify sounds such as chainsaws, motors and gunshots, and then relay alerts to forest rangers, activists and Indigenous groups.

wildlife ecologist Andy Whitworth gestures upward with his right hand while holding an oar on his lap.

This could monitor the movement of people, or the peccaries and tapirs that isolated groups hunt.

The challenge is to create and power durable devices that can withstand the brutal tropical humidity, heat and Sun for months at a time, says Whitworth.

As one of Forsyth's grant recipients, he is now working with separate teams to field test a prototype miniature camera that would use cloud-based artificial intelligence to sift through images.

Los Amigos has provided a real-life test for these technologies.

Beginning in 2016,

illegal loggers started building a road through the farthest reaches

of the concession. By 2019, they had made it into the adjoining

Madre de Dios reserve, where Mashco Piro roam among some of the last

remaining stands of valuable old-growth mahogany in the Amazon.

Backcountry rangers with

military experience worked with Indigenous guides to document the

intrusion, in part using drones and satellite data, including

high-resolution imagery and data from radar sensors that can peer

through clouds and tree foliage.

For Forsyth, the lessons from the past few years are clear.

Illegal gold mining has transformed a once-forested region in La Pampa, Peru, into a wasteland of sand dunes and ponds polluted with mercury.

Hidden peoples

Gutiérrez says the decision on whether to establish some kind

of monitoring system for isolated communities rests with governments

and Indigenous groups, but few doubt that it is possible.

Greg Asner, an ecologist at Arizona State University in Tempe, regularly captured evidence of encampments of isolated groups more than a decade ago, when his team was surveying the Peruvian Amazon in a plane equipped with a powerful laser-based system that provides 3D images of the forest.

He flagged the images to his sources at Peru's environment ministry, but never saw the groups themselves as a legitimate research topic.

Even today, he doesn't see the value in actively tracking them.

Despite the ethical worries about monitoring, some Indigenous leaders are open to the idea. Knowing where isolated groups are could help surrounding Indigenous communities to prevent unintended and dangerous contact, but,

...says Julio Cusurichi,

president of FENAMAD, which has worked with the Peruvian government

to prevent contact and conflict since the Mashco Piro began to

emerge.

Twenty years later, however, the reserve's borders have yet to be finalized, and the Indigenous organization is still pushing to expand the eastern boundary to cover areas where the Mashco Piro are known to roam.

The problem is that these same areas are currently occupied by logging concessions, which would be costly for the government to cancel.

president of the Native Federation of the Madre de Dios River and Tributaries (FENAMAD).

Too often, he contends,

the government is more concerned with protecting economic interests

than the rights of isolated peoples.

Officials from the

culture ministry acknowledged these dangers in discussions with

Nature, and said they were looking at potential regulations to

control the flow of information and restrict who can peer into the

reserves.

In Brazil, critics have accused President Bolsonaro, a right-wing populist, of sidelining scientists at FUNAI and attempting to appoint a former Christian missionary to head the division that handles isolated peoples.

In the Madre de Dios region, the former governor, Luis Hidalgo Okimura, disappeared in February just before he was to be jailed in connection with an investigation into an illegal logging ring.

He places more faith in Indigenous organizations and their advocates.

For the past few years,

her team has been training Indigenous groups to use drones and

satellites to patrol their lands and waterways; one of the

beneficiaries of that work is Tayori and his team at the Amarakaeri

reserve.

The software provides deforestation alerts, which are generated by an automated system that uses imagery from US satellites and was developed by scientists at the University of Maryland in College Park.

When Tayori checked his

phone, several alerts appeared on a map, and we motored upstream.

The week before we arrived, the leader of Diamante was arrested for taking bribes from drug traffickers, who had been using the town's airstrip to haul cocaine out.

Tayori sees similar challenges arising in his home territory.

Deforestation on the Amarakaeri reserve spiked during the pandemic, and Tayori says that problems continue to this day.

And even more alarming:

What's happening on the Amarakaeri reserve today is a reminder that science and conservation are only parts of a larger equation.

Tayori says Indigenous

communities and organizations have been looking for ways to protect

their lands while promoting sustainable economic development.

International funding could help on this front, but he and other

Indigenous leaders say that people on the ground have rarely

benefited from such aid in the past.

The younger generation is increasingly abandoning the traditional way of life and embracing a damaging culture of accumulating wealth and possessions, he says.

The result is a fraying of the security cordon that communities across the Amarakaeri reserve have been building to protect their territory in Madre de Dios.

Although he is pessimistic that traditional Indigenous culture will survive, Tayori expresses some hope that a growing movement of Indigenous activism will generate something new,

In essence, Tayori says

the Indigenous movement and its partners must devise a sustainable

social and economic model that will allow people to thrive in a

standing forest, else it will inevitably come down, tree by tree.

***

|