|

by Rod Nickel

August 10,

2018

from

ThomsonReutersFoundation Website

There is a proliferation of startup companies with

new visions of advanced GMO technology to modify the

human food supply.

Technocrats believe that every problem facing man

requires a scientific solution.

Where there is no obvious problem, one will be

created and then solved.

In this case, the long-term effect of modifying the

food chain is totally unknowable.

Source

INSIGHT-Gene-editing startups ignite the next 'Frankenfood' fight

In a suburban Minneapolis

laboratory, a tiny company that has never turned a profit is poised

to beat the world's biggest agriculture firms to market with the

next potential breakthrough in genetic engineering - a crop with

"edited" DNA.

Calyxt Inc, an eight-year-old firm

co-founded by a genetics professor, altered the genes of a soybean

plant to produce healthier oil using the cutting-edge editing

technique rather than conventional genetic modification.

Seventy-eight farmers planted those soybeans this spring across

17,000 acres in South Dakota and Minnesota, a crop expected to be

the first gene-edited crop to sell commercially, beating out Fortune

500 companies.

Seed development giants such as,

...have dominated

genetically modified crop

technology that emerged in the 1990s.

But they face a wider

field of competition from start-ups and other smaller competitors

because gene-edited crops have drastically lower development costs

and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has decided

not to regulate them...

Relatively unknown firms including,

...are already advancing

their own gene-edited projects in a race against Big Ag for

dominance of the potentially transformational technology.

"It's a very exciting

time for such a young company," said Calyxt CEO Federico Tripodi,

who oversees 45 people.

"The fact a company

so small and nimble can accomplish those things has picked up

interest in the industry."

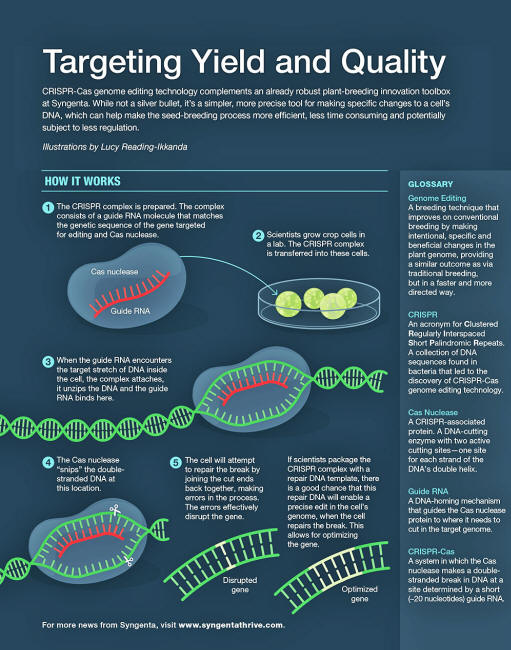

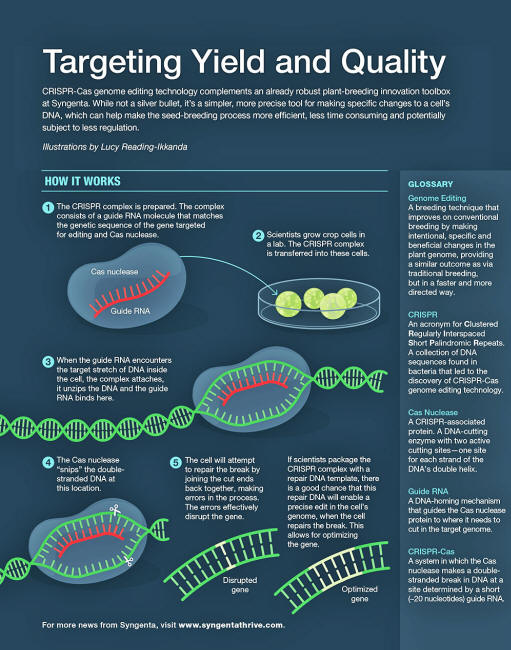

Gene-editing technology involves

targeting specific genes in a single organism and disrupting those

linked to undesirable characteristics or altering them to make a

positive change.

Traditional genetic

modification, by contrast, involves transferring a gene from one

kind of organism to another, a process that still does not have full

consumer acceptance.

Gene-editing could mean bigger harvests of crops with a wide array

of desirable traits:

better-tasting

tomatoes, low-gluten wheat, apples that don't turn brown,

drought-resistant soybeans or potatoes better suited for cold

storage...

The advances could also

double the $15 billion global biotechnology seed market within a

decade, said analyst Nick Anderson of investment

bank Berenberg.

The USDA has fielded 23 inquiries about whether gene-edited crops

need regulation and decided that none meet its criteria for

oversight.

That saves their

developers years of time and untold amounts of money compared to

traditional genetically modified crops. Of those 23 organisms, just

three were being developed by major agriculture firms.

The newly competitive landscape could foster more partnerships and

licensing deals between big and small firms, along with universities

or other public research institutions, said Monsanto spokeswoman

Camille Lynne Scott.

Monsanto - which was

recently acquired by Bayer AG - invested $100 million in startup

Pairwise Plants this year to

accelerate development of gene-edited plants.

North Carolina-based Benson Hill, founded in 2012 and named

after two scientists, mainly licenses crop technology to other

companies. But it decided to produce its own higher-yielding corn

plant because of the low development costs, said Chief Executive

Matt Crisp.

Calyxt plans to sell the oil from its gene-edited soybeans to food

companies and has a dozen more gene-edited crops in the pipeline,

including high-fibre wheat and potatoes that stay fresh longer.

Developing and marketing a traditional genetically modified crop

might easily cost $150 million, which only a few large companies can

afford, Crisp said.

With gene-editing, that

cost might fall as much as 90 percent, he said.

"We're seeing a huge

number of organizations interested in gene-editing," Crisp said,

referring to traditional crop-breeding companies, along with

technology firms and food companies.

"That speaks to the

power of the technology and how we're at a pivotal point in time

to modernize the food system."

UNCERTAIN

REGULATORY, PUBLIC ACCEPTANCE

Supporters of gene-editing say it allows a higher level of precision

than traditional modification.

With

CRISPR, one popular type of

gene-editing technology used by Syngenta, scientists transfer an RNA

molecule and an enzyme into a crop cell. When the RNA encounters a

targeted strand of DNA inside the cell, it binds to it and the

enzyme creates a break in the cell's DNA.

Then, the cell repairs

the broken DNA in ways that disrupt or improve the gene.

Graphic on how

the

Syngenta process works

https://tmsnrt.rs/2KJmtxr

Biotech firms hope the technology can avoid the "Frankenfood" label

that critics have pinned on traditional genetically modified crops.

But acceptance by

regulators and the public globally remains uncertain.

The Court of Justice of the European Union ruled on July 25 that

gene-editing techniques are subject to regulations governing

genetically modified crops.

The ruling will limit gene-editing in Europe to research and make it

illegal to grow commercial crops. The German chemical industry

association called the decision "hostile to progress."

U.S. Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue blasted the ruling

for enacting unnecessary barriers to innovation and stigmatizing

gene-editing technology by subjecting it to the EU's "regressive and

outdated" regulations governing genetically modified crops.

The USDA also has no current plans to regulate gene-editing in

animal products, according to a document provided by the agency.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, however, plans to regulate

gene-editing in both plants and animals, FDA Commissioner Scott

Gottlieb wrote in a June blog post.

The agency is developing

an "innovative and nimble" approach to regulating gene-editing, he

wrote, that will aim to ensure its safety for both humans and

animals while allowing companies to bring beneficial products to

market.

The USDA, by contrast, chose not to regulate gene-edited crops

because the process typically introduces characteristics that are

"indistinguishable" from those created through traditional plant

breeding, which take much longer, USDA Secretary Perdue said in a

March statement.

Although there has been no widespread consumer resistance to

gene-editing, activists who have long opposed genetically modified

crops remain suspicious of any sort of tinkering with DNA.

The new technique raises

risks of creating undesired changes in the food supply and warrants

increased regulation, said Lucy Sharratt, coordinator of the

Canadian Biotechnology Action Network.

That kind of opposition is why agribusiness giant Cargill Inc is

pursuing gene-edited technology with caution, said Randal Giroux,

the firm's vice-president of food safety, quality and regulatory

affairs.

Cargill announced in February that it would collaborate with

Precision BioSciences to develop healthier canola oil, but is

proceeding slowly on agreements to store and transport other

companies' gene-edited crops pending clarity from regulators, Giroux

said.

"We really do want to

see gene-editing evolve in the marketplace," Giroux said. "We're

watching to see how consumers adopt these products and react to

these products."

SECRET

FIELD-TESTING

Other major agriculture biotech firms are moving more aggressively,

hoping to take advantage of lighter regulation to speed development.

A gene-edited crop may take five years to move from development to

commercialization in the United States, compared with a genetically

modified crop that could take 12 years, said Dan Dyer, head

of seeds development at Syngenta.

The firm is working on better-tasting tomatoes that take longer to

spoil and hopes to launch a gene-edited crop in the mid-2020s, said

Jeff Rowe, Syngenta's president of global seeds.

DowDuPont - at a secret location in

the U.S. Midwest - is field-testing waxy corn, a variety grown for

industrial purposes that has been edited for higher yields.

The company plans a

commercial launch next spring.

Smaller firms will be nipping at the heels of these massive

companies in the race to bring the next generation of genetically

engineered foods to market, said Robert Wager, a biology

faculty member at Vancouver Island University.

"The lack of

USDA-regulated status is a huge game-changer," he said, "for

universities and small startups to enter the market."

|