|

by Chris Tyree and

Dan Morrison

November

2018

from

OrbMedia Website

Fluorescing microscopic pieces of plastic

swirl

in a bottle of water during tests

at The

State University of New York in Fredonia.

The mercury sprints past 30 degrees Celsius most days on Brazil's

world-famous Copacabana Beach.

Marcio Silva has walked untold miles here

selling bottled water from a cooler

to local sun-worshippers and sunburnt tourists alike - half a liter

of convenient refreshment and defense against dehydration.

"I drink water

because water is life, water is health, water is everything,"

says Silva, who is 51. "I drink it and sell it to others."

"I don't want to sell something bad to people."

The water looks clear,

clean, unsullied. So does the bottle.

For some, it's a

container of convenience. For others, it's a hedge against dirty or

unsafe tap water.

Bottled water is marketed as the very essence of purity. It's the

fastest-growing beverage market in the world, valued at US$147

billion1 per year.

But new research by

Orb Media, a nonprofit journalism

organization based in Washington, D.C., shows that a single bottle

can hold dozens or possibly even thousands of microscopic plastic

particles.

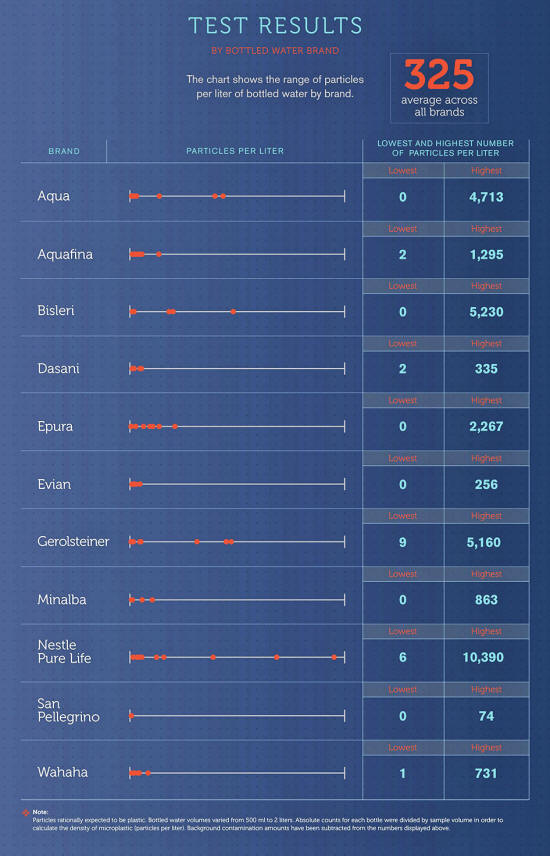

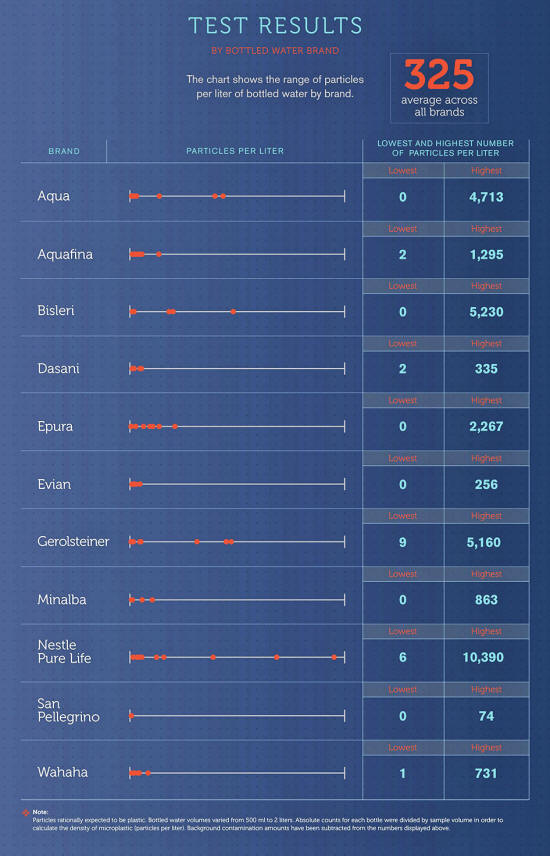

Tests on more than 250 bottles from 11 brands reveal contamination

with plastic including polypropylene, nylon, and polyethylene

terephthalate (PET).

When contacted by reporters, two leading brands confirmed their

products

contained microplastic, but they

said Orb's study significantly overstates the amount.

For plastic particles in the 100 micron, or 0.10 millimeter size

range,

tests conducted for Orb at the State

University of New York revealed a global average of 10.4

plastic particles per liter.

These particles were

confirmed as plastic using an industry standard infrared microscope.

The tests also showed a much greater number of even smaller

particles that researchers said are also likely plastic.

The global average for

these particles was 314.6 per liter.

"It's disheartening,

I mean, it's sad," said Peggy Apter, a real estate investor in

Carmel, Indiana. "I mean, what's the world come to? Why can't we

have just clean, pure water?"

Not the Milky Way:

Filtered from this single bottle of water,

fluorescing particles, most likely microplastics,

resemble the heavens on a cloudless night

when

viewed through a particle-counting app.

Some of the bottles we tested contained so many particles that we

asked a former astrophysicist to use his experience counting stars

in the heavens to help us tally these fluorescing constellations.

Sizes ranged from the width of a human hair down to the size of a

red blood cell. Some bottles had thousands. A few effectively had no

plastic at all.

One bottle had a concentration of more than 10,000 particles per

liter.

Bottled water evokes safety and convenience in a world full of real

and perceived threats to personal and public health.

Packaged drinking water is a lifeline for many of the 2.1 billion

people worldwide who lack access to safe tap water. 2 The danger is

clear: Some 4,000 children die every day from water-borne diseases,

according to the World Health Organization. 3

Humans need approximately two liters of fluids a day to stay

hydrated and healthy - even more in hot and arid regions.

Orb's findings suggest that a person who drinks a liter of bottled

water a day might be consuming tens of thousands of microplastic

particles each year.

How this might affect your health, and that of your family, is still

something of a mystery.

Findings

Bottles of water from the same brand

contained a wide range of plastic contamination,

with

particles as small as 6.5 microns.

This

variability is "similar to what is seen

when we

sample open bodies of water"

for

microplastic pollution,

Professor

Mason says.

Testing the

Waters

Bottled water manufacturers emphasized their products met all

government requirements.

Gerolsteiner, a German bottler, said its tests,

"have come up with a

significantly lower quantity of microparticles per liter," than

found in Orb's study.

Nestle tested six bottles

from three locations after an inquiry from Orb Media.

Those tests, said Nestle

Head of Quality Frederic de Bruyne,

showed between zero

and five plastic particles per liter.

None of the other

bottlers agreed to make public results of their tests for plastic

contamination.

"We stand by the

safety of our bottled water products," the American Beverage

Association said in a statement.

Anca Paduraru, a

food safety spokeswoman for the European Commission, said

that while microplastic is not directly regulated in bottled water,

"legislation makes

clear there must be no contaminants."

The U.S. doesn't have

specific rules for microplastic in food and beverages.

Our test of top bottled water brands from countries in Asia, Europe,

Africa, and the Americas was conducted at Professor Sherri Mason's

lab at the State University of New York in Fredonia, near the

Canadian border on the frigid banks of Lake Erie.

Mason's tests were able to record microplastic particles as small as

6.5 microns, or 0.0065 millimeters. The invisible plastic in bottled

water hides in plain sight.

To reveal it, Mason and her colleagues used a special dye, an

infrared laser and a blue light like those used by crime-scene

investigators.

Under a laminar airflow hood that sucks dust and airborne particles

up and away, each bottle was infused with a dye called

Nile Red that binds to plastic

polymer.

The dyed water was then

poured through a glass fiber filter.

When viewed through a microscope, under the blue beam of the

crime light, with the aid of orange goggles, the residue from each

bottle glowed with the flame-colored fluorescence of sometimes

thousands of particles.

"This is pretty

substantial," said Andrew Mayes, senior lecturer in chemistry at

the University of East Anglia, and developer of the Nile Red

method.

"I've looked in some

detail at the finer points of the way the work was done, and I'm

satisfied that it has been applied carefully and appropriately,

in a way that I would have done it in my lab."

The study has not been

peer reviewed.

Particles over approximately 100 microns were confirmed to be

plastic by both Nile Red and Fourier-Transform Infrared

Spectrometry (FTIR).

Because particles between

6.5 and 100 microns were not analyzed by FTIR, Mason left open the

possibility that their number could include other, unknown,

contaminants in addition to plastic, though rationally expected to

be plastic.

As with all science,

future methods may allow for even more accurate identification of

the tiny particles.

Why do you drink bottled water?

The plastic

inside us

So the bottled water you packed with your child's lunch may be

swimming with microplastic.

The short answer is that

scientists don't really know yet.

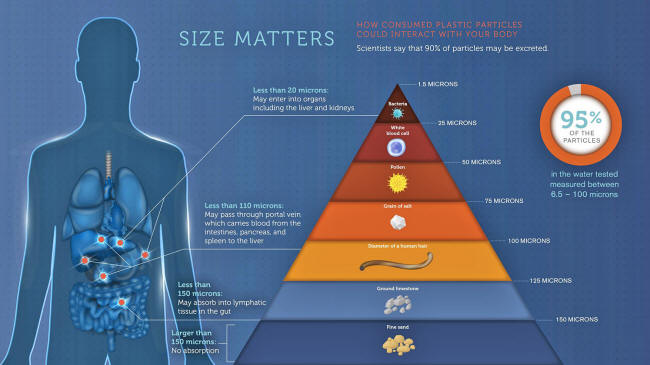

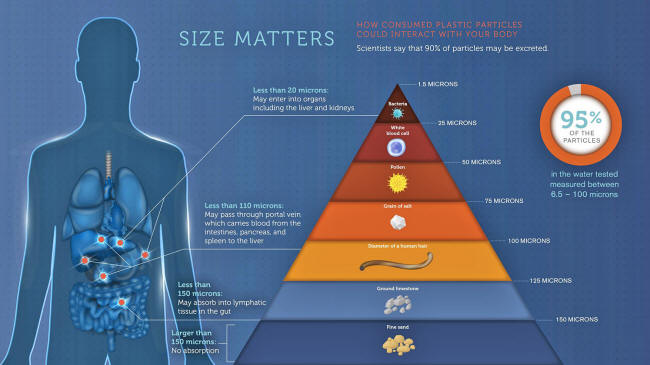

According to existing scientific research, the plastic particles you

consume in food or drinks might interact with your body in a number

of different ways.

As many as 90 percent of microplastic particles consumed might pass

through the gut without leaving an impression, according to a 2016

report on plastic in seafood by the European Food Safety

Authority.

What about the remaining ten percent?

-

Some particles

might lodge in the intestinal wall.

-

Others might be

taken up by intestinal tissue to travel through the body's

lymphatic system.

-

Particles around

110 microns in size (0.11 millimeters) can be taken into the

body's hepatic portal vein, which carries blood from the

intestines, gallbladder, pancreas and spleen to the liver.

-

Smaller debris,

in the range of 20 microns (0.02 millimeters) has been shown

to enter the bloodstream before it lodges in the kidneys and

liver, according to a 2016 report by the UN's Food and

Agriculture Organization.

-

Ninety percent of

the plastic particles we found in our bottled water test

were between 100 and 6,5 microns - small enough, according

to researchers, for some to cross the gut into your body.

But very little research

has been done on how frequently this might occur, or the health

burden it might represent - a knowledge gap that some researchers

say is in itself reason for concern.

United Nations

Food

and Agriculture Organization

Fluorescing particles that were too small to be analyzed by FTIR

should be called "probable microplastic," said Andrew Mayes,

senior lecturer in chemistry at the University of East Anglia,

because,

"some of it might be

another, unknown, substance to which Nile Red stain is

adhering."

Mayes developed the

Nile Red method for identifying microplastic.

De Bruyne, of Nestle, noted that Mason's tests did not include a

step in which biological substances are removed from the sample.

Therefore, he said, some of the fluorescing particles could be false

positives - natural material that the Nile Red had also

stained.

He didn't specify what

that material would be.

Mason noted that the so-called "digestion step" is used on

debris-filled samples from the ocean or the seashore, and wasn't

needed for bottled water.

"Certainly they are

not suggesting that pure, filtered, pristine water is likely to

have wood, algae, or chitin [prawn shells] in it?" she said.

Some researchers say

consuming microplastics in food and water might not be a serious

issue.

"Based on what we

know so far about the toxicity of microplastics - and our

knowledge is very limited on that - I would say that there is

little health concern, as far as we know," says Martin Wagner, a

toxicologist at the Norwegian University of Science and

Technology.

"I mean, that's quite

logical because I believe that our body is very well-adapted in

dealing with those non-digestible particles."

Martin Wagner

says, Orb's bottled water findings are,

"a very illuminative

example of how intimate our contact with plastic is."

"Plastic doesn't need to travel through the oceans and into fish

for you to consume it," he says. "You get it right from the

supermarket."

The 2016 evaluation by

the European Union estimated that for microplastics consumed with

shellfish,

"only the smallest

fraction may penetrate deeply into organs," 4 and

that our exposure to toxins through this contact is low.

But according to Jane

Muncke, managing director and chief scientist at the Food

Packaging Forum, a Zurich-based research organization, those

estimates are largely based on scientific models, and not laboratory

studies.

"What does it mean if

we have this large amount of microplastic bits in food?" Muncke

says.

"Is there some kind

of interaction in the gastrointestinal tract with these

microparticles... which then could potentially lead to chemicals

being taken up, getting into the human body?"

"We don't have actual experimental data to confirm that

assumption," Muncke says.

"We don't know all

the chemicals in plastics, even... There's so many unknowns

here. That, combined with the highly likely population-wide

exposure to this stuff - that's probably the biggest story here.

I think it's

something to be concerned about."

The Galaxies

We found a wide range of microplastic concentrations in the bottled

water we tested.

These images show a

selection of lab filters as seen through the black and white field

of the Galaxy Count app. Our study identified particles

between 100 microns and 6.5 microns.

Microplastics

are now found in all water sources

So what's best, bottled or tap?

Orb's 2017 tap water study and our current bottled water research

used different methods to identify microplastic within globally

sourced samples.

Still, there is room to compare their results.

For microplastic debris around 100 microns in size, about the

diameter of a human hair, bottled water samples contained nearly

twice as many pieces of microplastic per liter (10.4)

than the tap water samples (4.45).

Can the world's consumers stomach drinking microplastic?

"Please name one

human being on the entire planet who wants plastic in his or her

bottle," said Erik Solheim, executive director of the United

Nations Environment Program.

"They will all hate

it."

"It's the government's responsibility to educate people to know

what they're drinking and eating," Apter said, "and how we can

prevent this from continuing."

The tiny bits of plastic

swirling around in bottled water are a researcher's quarry and a

kitchen-table quandary.

People,

"have a right to

accurate and relevant information about the quality and safety

of any product they consume," said Lisa Lefferts, senior

scientist at the Center for Science in the Public Interest, a

U.S.-based advocacy organization.

"Since consumers are

paying a premium for bottled water, the onus is on

the bottled water companies to

show their product is worth the extra cost."

|