|

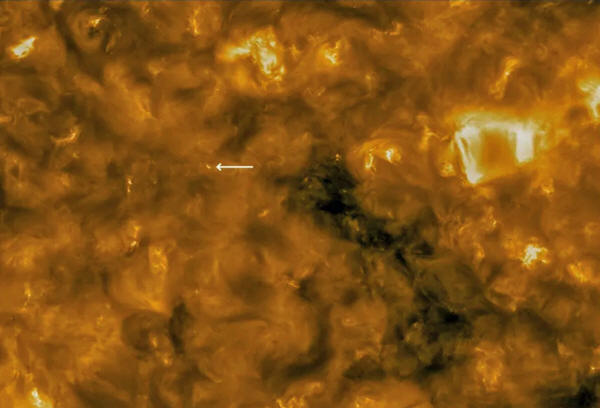

with an arrow pointing to one of the campfires

Image:

Solar Orbiter/EUI Team (ESA & NASA)

reveal tiny

solar flares dotting the star's surface.

This morning, the European Space Agency and NASA have unveiled the closest images of the Sun ever taken by a spacecraft:

Already, the pictures are revealing weird phenomena on the Sun that we've never seen in such detail.

Thanks to these images, scientists have discovered what appear to be relatively "tiny" solar flares peppered across the Sun's surface.

The scientists behind the mission have dubbed these small flares "campfires," as they are millions to billions of times smaller than the massive, energetic flares that periodically erupt from the Sun.

Dozens of these campfires can be seen at any given time within the field of view of Solar Orbiter's camera.

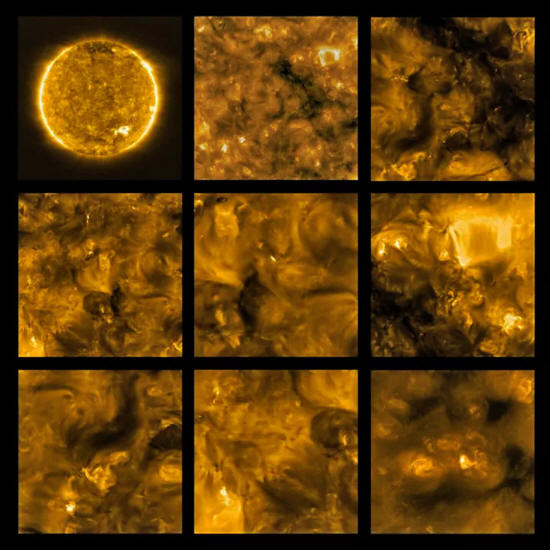

Solar Orbiter's first view of the Sun, taken on May 30th, 2020. Image: Solar Orbiter / EUI Team

(ESA &

NASA)

It's unclear exactly what is causing these mini-flares.

Typical solar flares often occur when the Sun is considered active - when dark sunspots pop up on the star's surface, causing parts of the Sun's magnetic field to twist and turn.

Such events cause tension to build up, and eventually, the magnetic field near the sunspot snaps, releasing a huge burst of highly energetic particles that speed forth from the Sun.

These campfires, however, do not appear to occur near sunspots or places of intense activity on the Sun.

In fact, the Sun has an 11-year cycle, where it oscillates between periods of extreme solar activity and periods of quiet - and right now, things are fairly quiet.

The discovery of these campfires is just the first major find of Solar Orbiter, a joint mission between ESA and NASA that launched on February 9th from Florida.

The spacecraft's mission is to get an unprecedented view of the Sun's poles, a vantage point that we haven't been able to see with any spacecraft before. It'll take about two years for Solar Orbiter to get into the right orbit to observe the polar regions of the Sun.

In the meantime, the vehicle has been testing out its suite of 10 scientific instruments - including its onboard cameras.

When Solar Orbiter captured these images, it was just 77 million kilometers - or nearly 48 million miles - away from the Sun. That's about half the distance between the Sun and the Earth.

No spacecraft has ever snapped images of the Sun's surface from such a close distance before.

of Solar Orbiter at the Sun.

Image:

ESA The images gathered by Solar Orbiter are about twice the spatial resolution of the pictures captured by NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory, which is currently in a very high orbit above Earth.

That spacecraft takes pictures of the Sun every day, while Solar Orbiter's image gathering is not as frequent.

Solar Orbiter will swing by Venus and Earth over the next year and a half in order to get closer to the Sun. Eventually, it'll reach its closest approach of the Sun, getting within 42 million kilometers, or 26.1 million miles.

That means the images are only going to get better over time...

Hopefully scientists will be able to learn more about these campfires and what's driving them.

They're curious if these mini-flares might explain a long-standing mystery:

Known as the corona, the atmosphere that surrounds is incredibly hot, even hotter than the Sun itself.

One theory suggested by astrophysicist Eugene Parker - the namesake of NASA's Parker Solar Probe - is that small solar flares are happening at small scales throughout the Sun, heating up the atmosphere.

It's much too early to say that these campfires are the source of the Sun's super hot atmosphere.

The scientists will also need to do more extensive observations to figure out the temperature of these campfires to really establish a link. But the discovery is exciting, and Daniel Müller is optimistic:

|