|

by Harry Pettit

Deputy

Technology and Science Editor

February 18, 2022

from

The-Sun Website

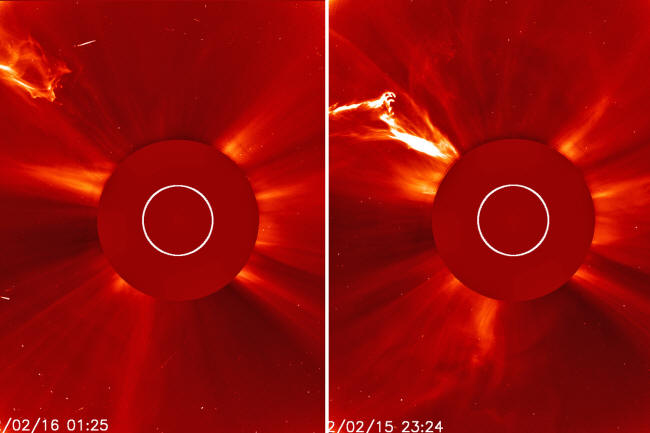

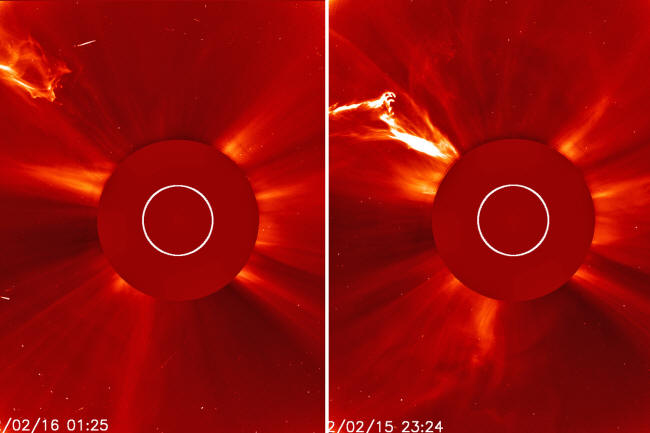

A huge plume of hot plasma (white)

erupted

from the Sun on Tuesday

Credit:

Nasa SOHO

On Tuesday, our star fired off two enormous explosions from its

farside in what has already been a heavy month of solar activity.

A magnificent coronal mass ejection (CME)

was recorded by NASA's

STEREO-A spacecraft in the early

hours of February 15 (pictured). CMEs are giant eruptions that send

plasma hurtling through space - and the Sun has undergone several of

them throughout the month.

If they hit Earth, the plumes of material can trigger geomagnetic

storms that knock out satellites and disrupt power grids.

Fortunately, this week's CME was fired from the side of the Sun that

faces away from our planet and so poses no threat, says astronomer

Dr. Tony Phillips.

Writing on his website

spaceweather.com, which tracks the

sun's activity, he said:

"This CME will not

hit Earth; it is moving away from, not toward our planet.

However, if such a

CME did strike, it could produce a very strong geomagnetic

storm. We may have dodged a bullet."

Based on its size, it's

possible that the eruption was an X-class flare:

The most powerful

category possible...

"This is only the

second far side active region of this size since September

2017," astronomer Junwei Zhao of Stanford

University's helio-seismology group told SpaceWeather.

"If this region

remains huge as it rotates to the Earth-facing side of the

Sun, it could give us some exciting flares."

It's been a busy month of

solar activity.

The Sun has erupted every

day for the month of February, according to Dr Phillips. Some days

have seen multiple solar flares. Three of them have fallen into the

second-most powerful flare category, M-class flares.

January saw five M-class

flares.

One such flare led to

a solar storm on January 29 that knocked 40 SpaceX satellites

out of action.

The rest of the flares in February have fallen into the milder

C-class category.

While it might sound

frightening, it's all part of our Sun's normal activity - so there's

no need to panic just yet.

Astronomers keep a close eye on the Sun's activity to ensure that

there is plenty of warning before any potential geomagnetic storm

hits.

What are geomagnetic

storms?

Geomagnetic storms are caused by

CMEs, which are huge expulsions of hot material called plasma

from the Sun's outer layer.

They can lead to the appearance of colorful auroras by energizing

particles in our planet's atmosphere.

Each solar storm is

graded by severity on a scale of one to five with,

a G1 described as

"minor" and a G5 as "extreme"...

At the upper end of the

scale, storms wreak havoc on our planet's magnetic field, which can

disrupt power grids and communications networks.

"Harmful radiation

from a flare cannot pass through Earth's atmosphere to

physically affect humans on the ground," NASA says.

"However - when intense enough - they can disturb the atmosphere

in the layer where GPS and communications signals travel."

When have major

geomagnetic storms hit Earth?

In the past, larger solar flares have wreaked havoc on our planet.

In 1989, a strong solar eruption shot so many electrically charged

particles at Earth that the Canadian Province of Quebec lost power

for nine hours.

As well as causing issues for our tech, they can cause harm to

astronauts working on the International Space Station, either

through radiation exposure or by interfering with mission control

communications.

The Earth's magnetic field helps to protect us from the more extreme

consequences of solar flares.

Weaker solar flares - which are far more common - are responsible

for auroras such as the Northern Lights.

Those natural light displays are examples of the Earth's

magnetosphere getting bombarded by solar wind, which creates the

bright green and blue displays.

The sun is currently at the start of a new 11-year solar

cycle, which usually sees eruptions and flares grow more intense

and extreme.

These events are expected to peak around 2025 and it's hoped the

Solar Orbiter will observe them all

as it aims to fly within 26 million miles of the sun.

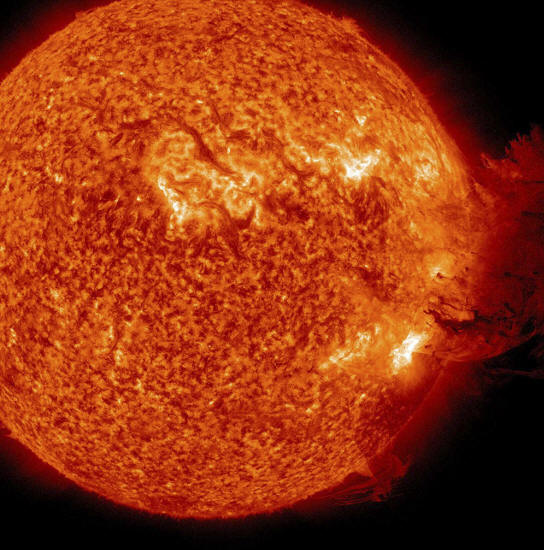

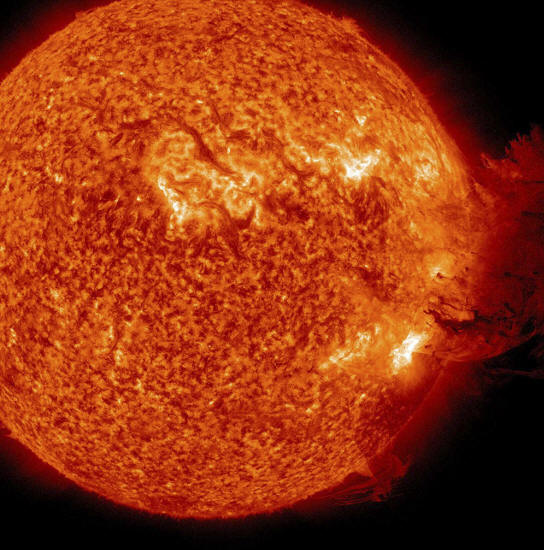

Solar eruptions can knock out

orbiting satellites and power grids on Earth

Credit: Reuters

|