|

by Monisha Ravisetti

from

Space Website

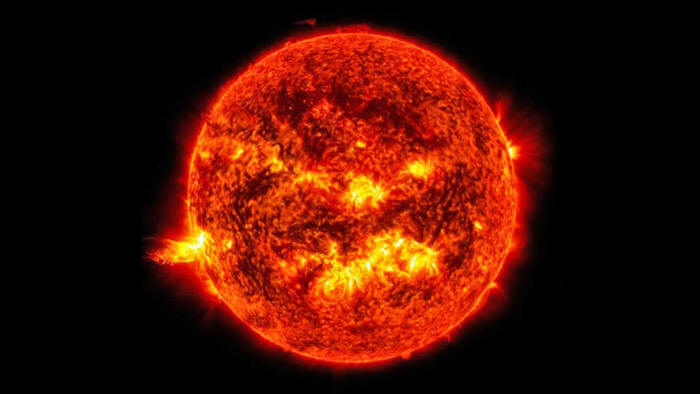

(Image

credit: NASA/SDO) we had this star figured out, but that's not the case."

This is quite a big deal

as it marks the highest-energy radiation to ever be documented

coming from our planet's host star.

Upon deliberation, however, the team realized that such brightness definitely existed - and it was simply due to the sheer amount of gamma rays the sun seemed to be spitting out.

Before you start worrying, no, these rays can't harm us.

But what they can do is

have a pretty important ripple effect for the future of solar

physics. In fact, they have already raised some important questions

about the sun, such as what role its magnetic field might play in

the newly observed gamma-ray phenomenon.

to the High-Altitude Water Cherenkov Observatory Collaboration. (Image credit: Courtesy of the HAWC Collaboration)

In short, this observatory, completed in the spring of 2015, is a facility specifically designed to observe particles associated with very high-energy gamma rays and cosmic rays, the latter of which are equally energetic but also mysterious in that they often travel across the universe without exhibiting a clear starting point.

HAWC basically uses a network of 300 large water tanks, a press release on the new study explains.

Each of these tanks is filled with about 200 metric tons of purified water, and they all sit nestled between two dormant volcano peaks in Mexico more than 13,000 feet (3,962 meters) above sea level.

All of this purified

water is important because, as high-energy particles from space

strike the liquid, the collision

results in a phenomenon known as Cherenkov radiation (which you may

have heard of if you've watched the TV show "Chernobyl").

High-Altitude Water Cherenkov Observatory in Mexico observing particles, whose paths are shown as red lines, generated by high-energy gamma rays from the sun. (Image credit: Mehr Un Nisa)

The recent gamma-ray

discovery doesn't seem to be associated with that kind of scenario.

The first time scientists observed gamma rays with energies of more than a billion electron volts, according to the release, was in 2011 with NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope.

But Fermi had a limit. It maxed out at finding gamma rays with about 200 billion electron volts.

So in 2015, the new study's research team started collecting gamma ray data with HAWC as this observatory didn't seem to have the same restriction.

Which brings us to the present - the first time we've seen sun rays with energies extending into a trillion electron volts.

And, according to Nisa, that does not appear to be the maximum.

The paper (Discovery

of Gamma Rays from the Quiescent Sun with HAWC) was

published Thursday (Aug. 3) in the journal Physical Review Letters

|