|

New Dawn Special Issue Vol 12 No 3

(June

2018)

GRAPHIC CREDIT:

© DARREN CARVILLE

We are confident that we

can understand these things through economics, psychology, race

relations, religion, or as a reaction to 'modernity' or to some

other factor that we can reason about, analyze, come to decisions on

and take steps to alter and improve.

We can, if not eliminate the more catastrophic events like wars, at least minimize the disruptions they cause. In short, we believe we control our fate - or will be able to sometime soon.

That is the whole modern project: man applying his intellect and will in order to make a better world, working to control events rather than be controlled by them, and steering history toward progress.

We are not there yet, but

it is just a matter of time.

We know that for a great part of human history that is exactly what many people believed.

Until the advent of what we know as science in the early seventeenth century, the belief that the stars ordered our destiny was commonly accepted.

Astrology, the art of foreseeing the turn of events on earth by charting the movements of the stars in the heavens, had for millennia guided emperors and kings the world over.

In ancient China, India, and the Middle East, in classical Greece and Rome and throughout Europe in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the belief that,

...was as much common knowledge as the supposed Big Bang is today. 1

And that this arrangement was hierarchical, with changes in the heavens portending those on earth, was also accepted.

It was generally agreed

that the earth and everything on it was open to forces coming from

beyond and that the wise men of antiquity understood these forces

and benefited by them.

The irony here is that some of the most significant figures in the rise of the modern scientific view of the world were well-steeped in the very 'nonsense' they were ostensibly freeing us from.

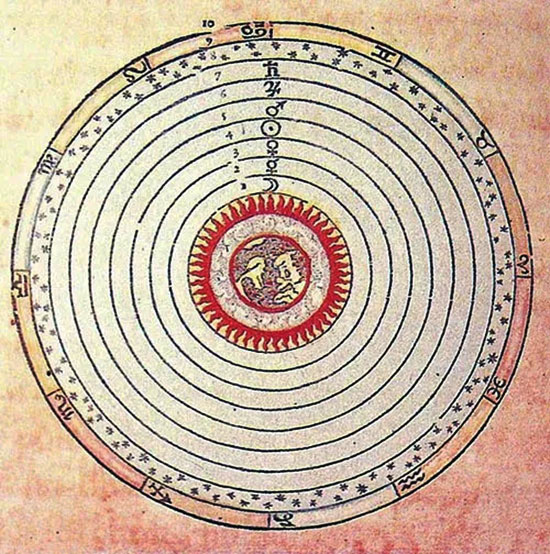

engraving by Andreas Cellarius,

1660

In On The Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres (1543) Copernicus argued - reluctantly it seems - that, as we all accept today, the sun did not orbit the earth, but the earth the sun. 3

It, not ourselves, was at

the centre of things, or at least that of our solar system.

Yet the idea that the sun was at the heart of things did not arrive in Copernicus' mind fully formed.

As the historian

Frances Yates argued some years ago - and as has been echoed

more recently by others - Copernicus was an attentive reader of the

Hermetic texts in which the sun plays a dominant, we might even say,

central role. 5

It has its roots in the teachings of the great sage Hermes Trismegistus, father of magic and science and initiate of the perennial philosophy, collected in the Corpus Hermeticum and other texts, circa 200 CE.

In Book XVI of the Corpus Hermeticum, Hermes calls the sun the "craftsman," Plato's name for the demi-urge, creator of the universe.

In the Asclepius - a Hermetic text not in the Corpus Hermeticum - Hermes speaks of the sun's "divinity and holiness" and calls it a "second god."

the earth was seen as the manifest physical realm at the centre of a series of concentric spheres which represented the planets, stars and higher levels in the Divine hierarchy of Being. The Ptolemaic model - which was official theory in Europe until after the Copernican revolution - had the earth in a stationary position

at the centre of the universe.

These are Pythagoras (who, we know, heard the 'music of the spheres') and his follower, the teacher of Plato, Philolaus. Copernicus even refers directly to the sun as a "visible god," just as the Asclepius does.

The fact that in the

Hermetic cosmology the sun's position differs from its place in the

Ptolemaic system that Copernicus was 'improving', suggests that it

was an important influence on those improvements.

The seventeenth-century German astronomer Johannes Kepler, who discovered the laws of planetary motion, devoted much time to astrology and forecast more than one dignitary's fortune, although he was not always happy about it.

He was also for a time a guest of Rudolf II, the Hermetic Holy Roman Emperor, a patron and student of astrologers. 6

Kepler recognized that much astrology was moonshine - at least that was true of his competition.

But he also knew that the

genuine baby should not be thrown out with the phony bathwater.

And as astrology is also known as an 'occult science' - 'occult' meaning 'unseen' - then Newton was a Hermeticist even when he did write about gravity which is also unseen.

As with Copernicus, there

is much debate today over how much Newton's Hermetic ideas informed

the Principia (1687), the blueprint for the modern, Newtonian

view of the cosmos, which, ironically, ousted the earlier, more

'magical' one. 8

But it didn't go down without a fight...

As late as 1768, the German physician Franz Anton Mesmer, soon to add a word to our vocabulary, earned his doctorate with his dissertation on 'The Influence of the Planets on the Human Body'.

Mesmer did not consider himself an astrologer or occultist. He was a scientist who had discovered the medium through which the planets and the entire cosmos influence life on earth. Yet he could not escape astrology altogether.

The very word 'influence'

itself comes from astrology. It is the name Marsilio Ficino

gave to the stellar fluid that flows from the stars down to earth

and informs what happens here.

This was, like the astral influence, a fluid permeating the universe, like the nineteenth-century 'ether', linking everything to everything else, its cosmic flow keeping all in balance.

A side-effect of the 'magnetic passes' that Mesmer and the mesmerists that received his training made over patients was what became known as the 'magnetic trance'.

It was a student of Mesmer, the Marquis de Puységur, who in 1785 stumbled on to what was really at work. 9

The 'trance' was not magnetic, animal or otherwise, but hypnotic - the term was coined by the Scot James Braid in 1842.

While Mesmer might not have grasped the phenomenon of hypnosis, he may not have been as wrong about magnetism as the members of the French Academy of Sciences, who in 1784 declared his work a fraud, believed.

and his wife Françoise. His scientific analysis of astrological correspondences, which were later confirmed by fellow scientist and staunch skeptic Hans Eysenck,

revealed they did play a role in human life.

Then in the mid-twentieth century science, of all things, seemed to come to its aid.

In 1955 Michel Gauquelin, a French psychologist and statistician with degrees from the Sorbonne, published a book L'influence des astres ('The Influence of the Stars') based on years of research that seemed to support some of astrology's fundamental ideas.

This work, as well as the English editions of his other books,

...made Gauquelin astrology's most persuasive scientific defender, although, like Mesmer, he did not see himself as an astrologer.

Gauquelin and his collaborator, his wife Françoise, said they simply wanted to answer a basic question:

After submitting the 27,000 + birthdates they had gathered to statistical analysis, the initial results were disappointing.

There seemed to be no substantial correspondence between one's 'sun sign' (Capricorn, Aries, Pisces, etc.) - the constellation the sun is 'in' at the time of one's birth - and one's destiny.

But the Gauquelins seemed to have discovered something else.

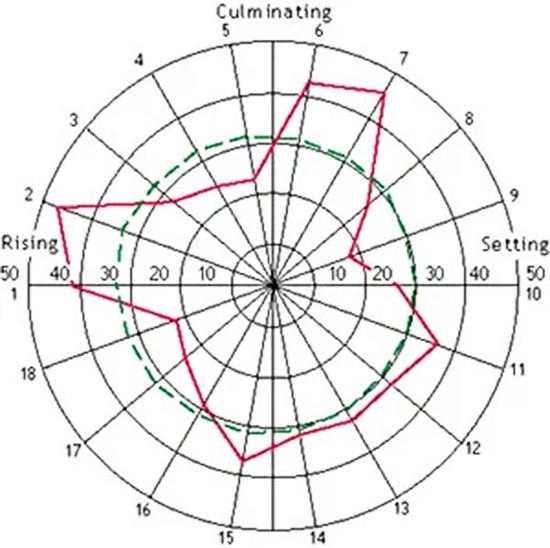

The Gauquelins discovered that more famous doctors were born just after the rise or culmination of Mars or Saturn - planets related to that vocation - than chance should have allowed.

Top-ranking military leaders were born just after the rise or culmination of Mars or Jupiter; again the astrological correspondence held.

Professions which in traditional astrological lore were associated with the other inner planets - Mercury and Venus - showed similar correlations.

As Guy Lyon Playfair and Scott Hill say in The Cycles of Heaven,

And there was another odd fact: these significant results were true only of people who were highly successful at their work.

The Gauquelins saw that large numbers of scientists, doctors, athletes, artists, writers and others, who were competent but not above average, fell outside their select group. It was as if the smaller number received the planetary influence - whatever it was - direct and absorbed it all, leaving very little for the stragglers.

Gauquelin's findings have

come to be known as 'the Mars Effect'.

'The Mars Effect' (red)

illustrated on this chart.

Eysenck, a tough-minded skeptic, had to admit that he was convinced.

And when Eysenck and his

colleagues examined some other astrological givens - that people

born under 'water' signs tend to be emotional, that those born under

'odd' numbered signs tend to be extroverted while those born under

'even' ones are introverted - he and his team were surprised to find

the evidence strongly in favor of them. 11

Some people working in the earlier part of the last century, and in another part of the world, thought they might have a clue.

At least in researching this article I came across more Russians than chance may have allowed.

For example, the Greek-Armenian esoteric teacher G.I. Gurdjieff may not have been Russian - his exact nationality has always been uncertain - but he certainly started his career in Russia. 12

In 1914, with the First World War erupting, the Russian philosopher P.D. Ouspensky, Gurdjieff's most famous pupil, asked him if such catastrophes could be avoided.

They could, Gurdjieff

told Ouspensky, but what was necessary was to understand why they

start.

The moon is the chief... motive force of all that takes place in organic life on earth. All movements, actions, and manifestations of people... depend on the moon and are controlled by the moon. Georges Ivanovich Gurdjieff

Gurdjieff also spoke to Ouspensky about the Moon.

Bookshelves are full of accounts of how the full moon affects some people; our terms 'lunacy', 'lunatic', 'looney', 'moonshine' are evidence of the popular acceptance of something that is still 'officially' dismissed.

Gurdjieff took it a bit further.

Perhaps the strangest

thing was Gurdjieff's insistence that the moon is a living being

and that it is growing, and that its nourishment comes from the

souls of 'sleeping' people who are not working to attain the true

'waking' state of consciousness. 15

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, one of the founders of the Theosophical Society, was, like Ouspensky, a full-blooded Russian.

In Isis Unveiled (1877) she writes that,

At times this influence promotes periods of withdrawal, of "monasticism and anchoritism"; at others frenzied action and "utopian schemes." And where Gurdjieff speaks of the "harmony of reciprocal maintenance" operating throughout the cosmos, Blavatsky speaks of the,

Blavatsky got her knowledge from her Masters in Tibet.

Did anyone in Russia have it too? Oddly, around the same time that Gurdjieff was enlightening Ouspensky about our place in the cosmos, it seemed someone did.

But in his case, the sun,

not the moon, pulled the strings.

He had become fascinated with the study of sun-spots - huge dark bodies that pass across the surface of the sun - and it struck him that at the same time as a large group of spots crossed the sun's central meridian, certain events transpired on earth.

The aurora borealis that month was unusually strong, and the magnetic storms making up the spots had disrupted more radio and telephone communication than usual.

But there was something else.

Was that a coincidence?

In 1917, when the

Bolsheviks took power, there was, he saw, another unusual burst of

solar activity. Checking the records, Chizhevsky saw that there had

also been one in 1905, at the time of an aborted uprising.

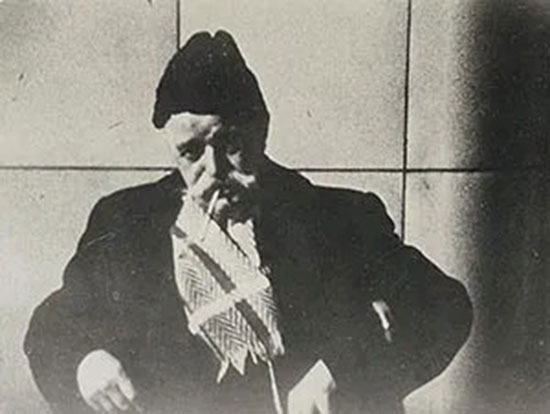

The young Soviet scientist Aleksandr Chizhevsky correlated the sun-spot cycle with major upheavals in human history. He is photographed here pointing to one of his charts.

These, he argued, came in regular cycles which coincided almost exactly with the eleven-year sun-spot cycle.

(In 1843, the German

astronomer Heinrich Schwabe observed that sun-spots went

through a ten-year cycle; the idea was later refined by Rudolf

Wolf and Alexander Humboldt and established at eleven

years.)

Every major outbreak in recent history, from the French Revolution to the start of World War I, was precipitated by solar excitement.

In 1926, guided by the sun-spot cycle, Chizhevky predicted important flare-ups from 1927 to '29.

What happened then?

Chizhevsky's work impressed many people, like the economist Edward Dewey, who used his ideas in his own work on economic cycles. Others, like Stalin, were not so impressed.

In 1942, when he realized that for Chizhevsky sun-spots and not the irresistible march of the Marxist class war were responsible for the Soviet Union, he ordered him to retract his work.

By this time Chizhevsky was a prestigious scientist, with many degrees and honors.

Alongside Nicolai Fedorov, Konstantin Tsilokovsky, and V. I. Vernadsky, he was one of what is known as the 'Cosmist' school.

He was released during the Khrushchev 'thaw' following Stalin's death and today is revered as the 'father of heliobiology', the study of the sun's influence on life on earth.

Other Russians who were

influenced by his work or shared his belief in cosmic forces

affecting the earth, were Vladimir Vernadsky, mentioned above, who

popularized the ideas of the 'biosphere' and 'noosphere', and the

historian Lev Gumilev, whose ideas about 'ethnoi' and 'passionarity'

as agents of civilization, also depend on cosmic forces affecting

human beings. 20

They worked as stimulants:

The ionization too went through cycles and at the highest concentration of negative ions, things start jumping. 21

Mesmer was not as wrong as his critics believed. Magnetism did have something to do with it. Chizhevsky died in 1964.

One odd fact that he missed but others, like Edward Dewey, noticed was that often things on earth occurred slightly ahead of the sun-spot cycle, as if effect preceded cause - or as if events on earth triggered the spots.

If this was the case, then something else must be responsible or at least precede both.

In 1949 John Nelson, an RCA engineer who had been studying the sun to 'predict' when its spots would interfere with communications, hit upon an answer.

Although most astronomers would laugh at the idea of a planet's weak magnetic field having any effect on the sun, this is exactly the conclusion Nelson came to, and which enabled him to predict and avoid blackouts. 22

The odd thing was that the planets' effect on the sun coincided with traditional astrological notions of 'opposition' and 'conjunction'. When planets were in such an arrangement with the sun and the earth, things tended to go haywire.

Otherwise, things were

fine...

In The Bond, Lynne McTaggart states that,

This is a not uncommon reflection on human hubris.

But it goes against what Chizhevsky himself believed: that the sun does not compel us to do anything in particular, only to do something. It acts as a stimulant; what we do when stimulated is up to us.

There may be increased

belligerence during intense sun-spot activity, but there are always

pacifists, conscientious objectors, and quiet people at home,

sitting out the riots.

This was something Gurdjieff knew when he told Ouspensky that one could choose which influences one fell under. 24

Man could escape being 'food for the moon' by working on himself and, in his interior planetary system - spelled out in fascinating detail by Rodney Collin, a student of Ouspensky, in The Theory of Celestial Influence - could become an 'inner sun', under a minimum of cosmic laws. 25

As its students know, this too was an aim of Hermeticism. 26

The stars in their

courses may spark events here on earth, but we still have the

responsibility of steering our way through them.

|

mmm

mmm