|

from

Medium Website

"Neo" skull of Homo naledi, on exhibit at Maropeng.

John Hawks CC-BY

The evolutionary story of modern humans

just got more

complicated...

Modern humans originated in Africa sometime around 200,000 years ago.

Some modern people spread

into other parts of the world sometime after 100,000 years ago,

mixing a bit with archaic human groups they met along the way.

They were far from alone:

The last month has seen more shake-ups to the modern human origins story than any time I can remember.

Here's what we have learned in the last few weeks about this key time period in Africa.

When geneticists first started measuring genetic differences between people, they realized that the population must have once been a lot smaller.

They came up with the

idea of a genetic "bottleneck", a period in which the human

population might have been very small.

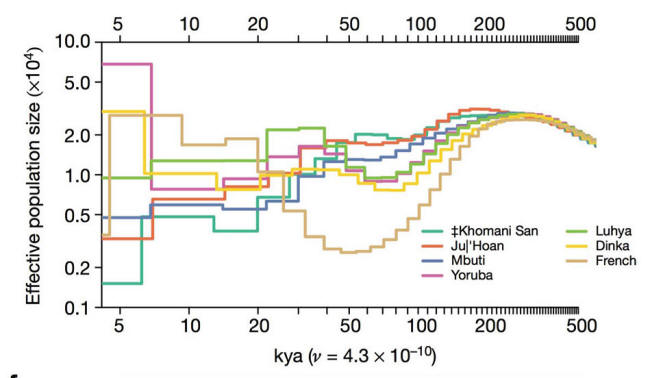

from different populations (indicated). The French underwent a clear bottleneck, starting between 100,000 and 50,000 years ago, which was actually shared by all other people outside Africa. But the African populations here had no strong bottleneck. The Khoe-San people in this chart have no sign of a bottleneck at all. From Mallick et al., 2016,

They have inherited most of their genes from a small population that grew and dispersed throughout the world. That dispersal carried that signal of a "founder effect" along with it. Those people further mixed a small fraction with archaic humans, the Neanderthals, and for a few, the Denisovans.

That founder effect

unfolded within the last 100,000 years.

Until this week, geneticists have thought that their ancestral lineage has existed for as long as 200,000 years. That origin, the deepest split between human populations that still exist, points to the stem population of all living people.

It doesn't divide

Africans from non-Africans, it reflects a deep history of diversity

among African populations - the founder effect leading to

non-African peoples was much later.

But there's an important

difference. By comparing his genome with the genes of living people,

Schlebusch and her coworkers found that today's Khoe-San have

received a lot of genetic mixture from other populations during the

last 2000 years.

Humans mix with each

other, and that mixture has increased in recent times. Very ancient

peoples mixed too, but migration and mixing were less in the distant

past than in recent history.

If we use today's genetic

diversity to try to work out the original ancestors of modern

humans, we're going to come up with an answer that is too recent,

because of these recently shared genes.

The answer was a lot

older, around 260,000 years ago. Modern populations, the

ancestors of living people, have been diversifying from each other

within Africa for at least that long.

So when we look back into the past, we are looking at populations that reticulated with each other.

But anthropologists really disagree about how to identify "modern humans" in the fossil record. A fossil that shares some human traits might be part of that delta network leading to some living populations.

But just as easily, it

might instead be off on its own branch, flowing until it disappears

into the desert sands.

So how can we recognize

them? And how many groups of them were there?

Old excavations carried out in the 1960s had produced parts of three skulls and some other human bones. Previous scholars had tried to work out the geological age of these remains, ultimately deciding they were around 150,000 years old.

Credit:

John Hawks CC-BY

These fossils and the

archaeological layer they come from are somewhere between 220,000

and 380,000 years old. That overlaps with the time

range of the first modern humans.

Do these fossils fit into the origin of modern humans somehow? Anthropologists are unanimous that the braincases of the Jebel Irhoud skulls don't look much like modern humans. They are elongated, with an angled cranial rear.

They aren't Neanderthals, but it would be a big stretch to connect them to living people.

compared to Jebel Irhoud 1 skull (bottom). The face of Jebel Irhoud is shorter than the Neanderthal, but it has a clear and continuous browridge, and its braincase is not very much like modern humans.

Photo

courtesy of Milford Wolpoff.

The faces of Jebel Irhoud 1, and the newly-discovered Jebel Irhoud 10, are a bit shorter, with cheeks are shaped more like modern humans than like Neanderthals.

The brows of Jebel

Irhoud 2 are reduced, like robust modern humans in their form,

although Jebel Irhoud 1 has a stout and continuous browridge.

The jaws from the site are robust and have big teeth, but they are

taller in the front than in the back, and the midline of the

jawbones are vertical.

The jaws lack that most

modern mandibular feature, the chin. Many of the humanlike aspects

of the face can also be found in some much older fossil remains,

such as the Homo antecessor fossils from Spain.

The paper describing this idea mentions another old fossil with a combination of archaic and modern features, a partial skull from Florisbad, South Africa, also clearly not modern human, but with a few humanlike features.

might be in this time range, but the date depends on a tooth that

may not

be the same context or individual.

They connect the

evolution of these early Homo sapiens people to a new form of

technology, the

Middle Stone Age, which was found

in various regions of Africa by 300,000 years ago.

Under the Hublin model,

there may have been none. Every fossil sharing some modern

human traits may have a place within the "pan-African" evolutionary

pattern. These were not river channels flowing into the desert,

every channel was part of the mainstream.

Geneticists think there were others...

The 2000-year-old Ballito Bay boy is not the oldest, but there are no DNA results from truly archaic specimens, like the Kabwe skull from Zambia.

As a result, we don't have the kind of record within Africa that geneticists have built for Neanderthals and Denisovans in Eurasia. But a series of genetic studies on living Africans have succeeded in identifying signs of mixture from ancient people.

This work, led by Michael Hammer, Jeff Wall, Joe Lachance, and others, is built upon a close examination of the genomes from living people.

What they are finding is

genetic ghosts...

Using those clues,

researchers are now able to identify "ghost populations", ancient

groups whose mixture with modern humans helps to explain some

aspects of diversity in African genomes today.

They were ancient

lineages with long histories, starting from long before any modern

humans existed, and they were mixing with modern populations as

recently as 20,000 years ago.

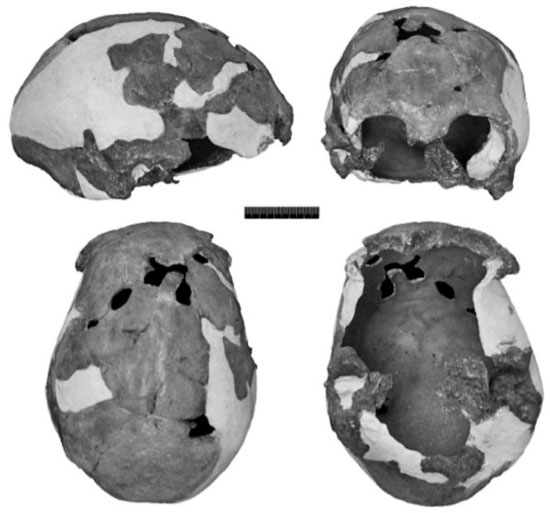

Skull from Iwo Eleru, Nigeria. Photo credit: Katerina Harvati and colleagues

CC-BY

Some anthropologists have

suggested possible candidates. One archaic-looking human skull,

found from Iwo Eleru, Nigeria, even existed during this latest part

of the Pleistocene when the last signs of mixture have been

identified.

But the river leading to

that delta was not one big channel; it was a braided series of

streams.

That dominant stream, that special population of human ancestors, lived sometime before 260,000 years ago.

Jebel Irhoud might have been on the mainstream, or it might have been part of one of the more minor contributing archaic groups, making up a percent or two of the genomes of living people.

Or it might belong to

a still more distant extinct branch, its facial features

inherited from very ancient ancestors like Homo antecessor and

marking no special relationship with any modern humans.

They cannot answer this question because they cover such a tiny fraction of the African continent...

"Neo" skull (left) compared to DH1 skull of Homo naledi (right).

Photo credit: John Hawks CC-BY

Last month, our team

published the first scientific assessment of the age of this new

species, between 236,000 and 335,000 years old.

It lived during the time that hominins were making Acheulean handaxes, and it lived as Middle Stone Age techniques began to proliferate in southern Africa.

We cannot assume that H. naledi wasn't the species that made these tools where it lived. We don't know what the interactions between H. naledi and other populations may have been.

The fossil record isn't good enough to say whether they existed in the same place as any other modern or archaic humans.

Omo 2 skull usually attributed to modern humans (right).

Photo

credit: John Hawks CC-BY

Many of the important fossils, like the Florisbad skull, and the Kabwe skull from Zambia, were recovered at a time when fossil contexts were not recorded with the level of precision as today.

Methods of direct dating such fossils have improved, but each advance means that old dates may not be trustworthy.

That is, after all, why we are talking about new dates for Jebel Irhoud right now.

The answer is to make

more discoveries...

One thing that H. naledi

reminds us is that the development of technology is a broader issue

than the origin of modern humans.

The answers to these

questions are not simple. Our evolution may have encompassed many

parts of Africa, but it certainly was not uniform, and right now it

looks like the subequatorial part of the story was especially

complex and interesting.

That's the way that we

will start to solve these new problems and shed light on old

mysteries...

|