|

by William Giovinazzo

March 25,

2020

from

ClassicalWisdom Website

When I was a kid, I was

taught by the good sisters of Saint Joseph that democracy is a

'wonderful' thing, something ordained by God.

In the United States

in the early 1960s, it was seen as God's gift to man, the

bulwark against godless communism.

Kennedy was

telling us that we needed to spread democracy throughout the world

as a radical idea that would free humanity from the shackles of

oppression.

We all stood proudly

before the American flag,

chest out, arms

akimbo, defenders of truth, justice, and the American way which

was decidedly democratic...

That is what we were

taught.

As with many things the

good sisters told me,

reality is a bit more complicated...

Marble statue of the ancient

Greek

Philosopher Plato.

Academy

of Athens,Greece.

In book 6 of Plato's

Republic, Socrates discusses

democracy with Adeimantus.

To describe the

shortcomings of democracy, Socrates uses the analogy of,

a ship whose crew

mutinies against their captain.

Although they have no

understanding of navigation or how to pilot a ship, they take

command.

When someone

disagrees with the ideas held by the crew, even those ideas

based on actual knowledge, the dissenter is jettisoned.

Decisions would be

made by the consent of the crew, all equal, regardless of

knowledge.

Is this the type

of ship you would choose if you were planning to undertake a

long journey?

Wouldn't you

rather have someone at the helm who is trained in piloting a

ship?

In plotting the

course, wouldn't you prefer to have someone who understands

navigation?

Yet,

a ship run by the

votes of the equal and unequal alike is how the democratic ship of

state is piloted.

Plato understood that such a ship is ripe fruit for a demagogue.

To demonstrate this

point, Socrates imagined an election between a doctor and a candy

store owner.

The doctor would tell

the populace what they didn't want to hear...

The Death of Socrates,

Jacques-Louis David, 1787.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

As Socrates described it,

the candy store owner

would say of the physician that he works many evils on you.

He hurts you, gives

you bitter potions, tells you not to eat and drink whatever you

like.

What fun is that?

The candy store

owner, however, would offer sweets and tasty things.

He would appeal to

what people wanted, not what they needed.

He would provide easy

and popular answers to all their difficult problems.

Democratic leaders who

value their position over what is right, or even what is good for

the country, have learned to be candy store owners.

They pander to whoever

will help them maintain power.

The result is a

vision not of the long-term future, but the next election....

Just consider one of the

many issues in today's headlines.

Do you raise taxes or

reduce spending? Neither! Simply raise the debt. Better yet,

increase spending and reduce taxes. So sweet. So tasty...

By the time the

repercussions of the decision become clear, if you are lucky,

you will be dead.

It will be someone else's

problem...

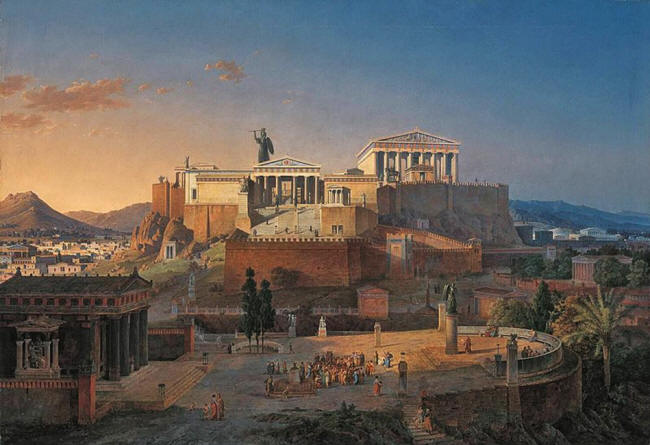

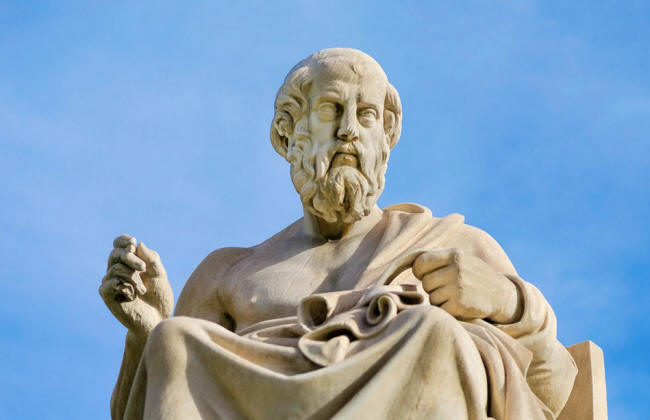

The Acropolis at Athens,

Leo von

Klenze (1846).

Democratic leaders are relatively free to do what they like, as long

as it is popular.

The masses have little

tolerance for complex reasoning and the minutia of various policies.

The clever demagogue will appeal to emotion, more concerned with

imagery than substance.

In democracies, political debates become superficial.

The focus is on how

the candidate is perceived.

Do they seem

presidential?

Are they strong and

decisive?

Do they tell it like

it is?

President

Bush seemed like the type of

person with whom people would like to have a beer.

This was seen as some

measure of his likability, an attribute, in the minds of

the masses, more critical than competence or knowledge.

Of course, Plato wrote

the Republic before the modern era and mass communication.

Technological advancement

only amplified the importance of a politician's public persona.

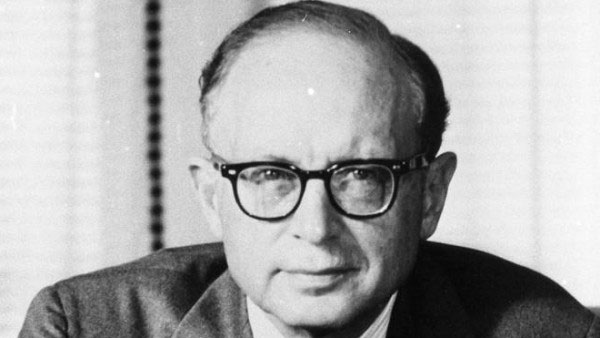

In 1962 Daniel J.

Boorstin published

The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America,

in which he describes how television and radio have created

pseudo-events, events that are staged with the intent to be reported

or reproduced and have an ambiguous relationship with the reality of

the situation.

Photo of

Daniel

J. Boorstin

The intent is to shape public opinion.

As Boorstin said:

"Some are born great,

some achieve greatness, and some hire public relations

officers."

These pseudo-events, such

as the presidential debates, reduce,

"great national

issues to trivial dimensions."

Boorstin likened the

debates to the quiz show The $64,000 Question.

If you answer the

questions correctly your prize is the presidency. Of course, the

correct answer here is defined as the most popular answer.

Boorstin was just one

milestone between Plato and ourselves.

Since the historian's

time, we have become subjected to the 24-hour news cycle where news

networks compete for a larger share of the viewing audience.

It was also well before the ubiquity of the internet and social

media. We live in an age of celebrity, where people are human

pseudo-events, as Boorstin describes them. They are known for their

well-knowness.

It is the time of

influencers, people who can affect the purchasing decisions of

others not necessarily based on their expertise, but the size of

their audience. It is a society of superficiality and little

substance.

Plato's predictions have

come through with a vengeance...

Thomas Coutre,

The

Romans in Their Decadence,

(Museo

de Orsay, 1847)

There is an even deeper challenge posed by democratic societies.

The ancient thinkers

understood that our politics could not be separated from our values.

In past societies, authority and values

flowed from the top down.

Gerhard Lenski in

Power and Privilege: A Theory of Social

Stratification showed

how religion,

supported the ruling

class, establishing conduct and values that gave legitimacy to

the authority of the governing elite...

In contrast, democracy's

authority flows up.

As we are told:

governments are

instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the

consent of the governed.

Along with the flow of authority, so too flows the values of the

people; that is to say, from the bottom up in democracies.

This creates a

chaotic situation in a pluralistic society with people of

differing cultures, differing values.

In this confusion, there

is no one definition of the good, no one set of values, to which one

can appeal.

Plinth of

kouros statue,

bas-relief depicting wrestlers,

circa

510 B.C.,

detail

from Kerameikos necropolis

in

Athens, Greece

When there is a lack of a

standard, individuals pursue their desires and interest.

Of course, such

individualism is not necessarily a social evil.

It becomes an issue,

however, when we become so self-absorbed that we become

unwilling to sacrifice for the common good.

Many today feel any

provision for the commons is seen as an intolerable threat to

liberty.

They see themselves as

buckskin-clad plainsmen staring steely-eyed into the horizon free of

all government encumbrances.

In looking at these shortcomings, Plato saw democracies not only as

morally confused with little agreement on values, but so focused on

image that political discourse is superficial.

Plato said,

"democracy is a

charming form of government full of variety and disorder, and

dispensing a sort of equality to equals and unequals alike."

Given these flaws,

it is not at all surprising that democracies are relatively

short-lived forms of government.

Unfortunately, Plato's solution for how best to govern ourselves is

just as unrealistic as democracies.

He proposed a regime

that is ruled by a philosopher-king. This may seem somewhat

self-serving: that a philosopher, Plato, believes that

philosophers should be king.

But this expression could

be a bit misleading...

Piazza del Campidoglio (Rome, Italy).

Statue

of Marcus Aurelius,

perhaps

the only person worth the name

of

"philosopher-king."

Plato

described the philosopher-king as,

a man who loved

wisdom more than power...

Such a leader would

understand the good.

His goodness and

moral leadership would pass down to the people providing society

a unified moral standard.

Such a vision is na´ve...

History has shown the

rarity of such leaders; it has proven that such a model is even less

sustainable than democracy.

"I have met the enemy

and he is us" to quote that ancient 'philosopher'

Pogo.

The flaw in democracy is

not the quality of the leaders, but of those that are led.

We, the people, need

to take responsibility to ensure good government.

We all must be

philosophers.

We cannot look to a

man (or woman) on a horse to rescue us.

We, the people, need

to ensure a society that promotes individual self-actualization.

We all must come to

love wisdom, to cherish what is good over what is profitable or

expedient.

Of course, believing that

the masses could, or even would, become lovers of wisdom

might turn out to be just as na´ve a solution as the others...

|